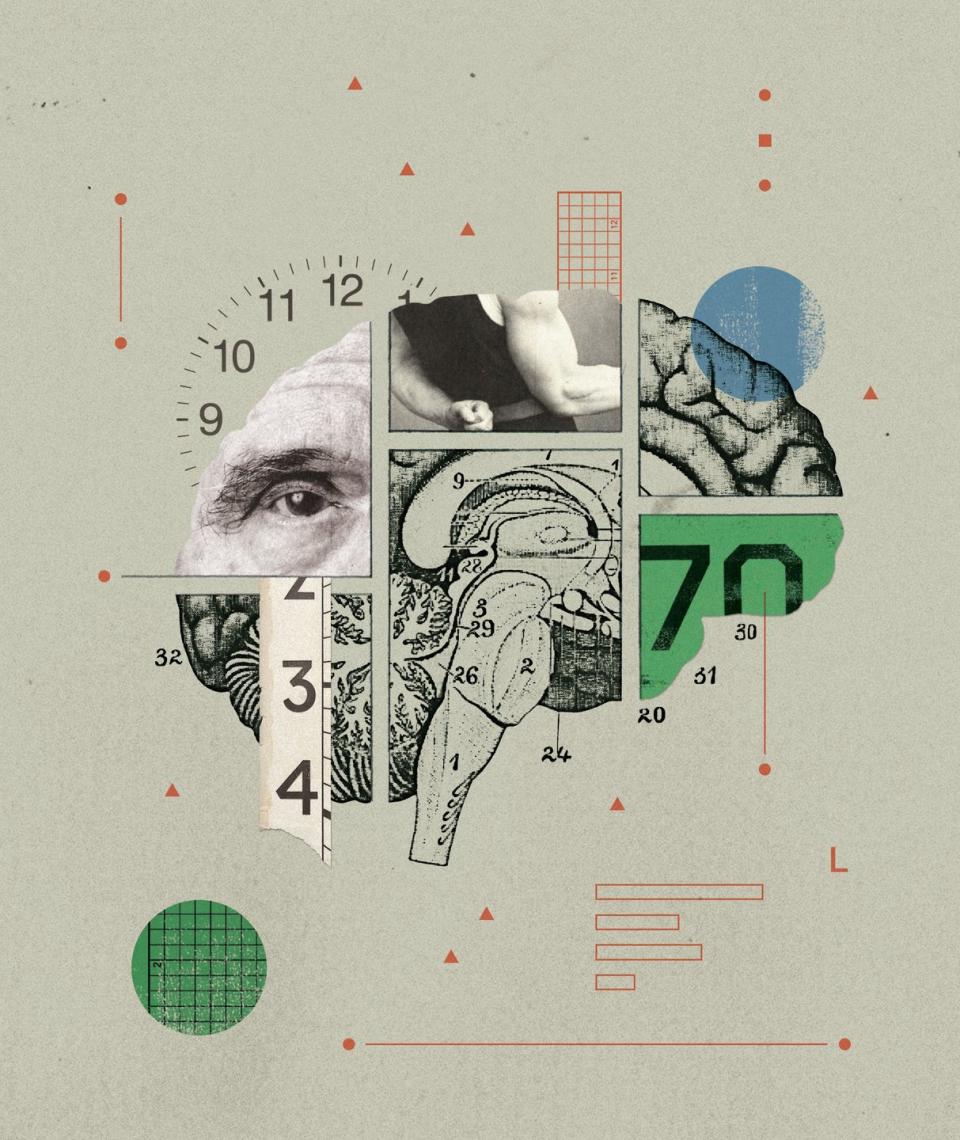

Is an 80-Year-Old Brain Fit for the Presidency?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

AFTER JOE BIDEN was sworn in as the oldest president in American history in 2021, at age 78, questions swirled about whether there should be an upper age limit for the executive office. Now that we’re doing a different kind of math—Biden would be 86 at the end of a second term, and his presumptive rival, Donald Trump, would be 82—the question has become starker: Can someone in their 80s really have the mental dexterity and cognitive fortitude that the office requires?

Physiologically, we can’t stop our brains from changing. They start shrinking about 3 percent per decade after age 40, and that accelerates to about 5 percent per decade in our 80s. Our information-processing speed slows down, and it’s harder to quickly retrieve info or tune out background noise. Those functions likely get gummed up due to the hardening of blood vessels and the buildup of plaque in the brain.

Yet scientists are challenging previous conceptions of what these changes actually mean in our day-to-day lives. We know that brain volume decreases, says Scott A. Kaiser, M.D., director of geriatric cognitive health at the Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica, California, “but that might not be all that important in terms of how the brain performs overall.” In fact, in some ways, an older brain is better equipped to manage the demands of a job that requires insight, emotional control, and good decision-making skills.

There’s also the question of how much someone’s age really matters, since it doesn’t necessarily define how their brain functions. “Every person develops a different amount of resilience and resistance to the passage of time,” says neurologist Marek Marsel Mesulam, M.D., at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

This is fueling a new cultural conversation around the idea that there are even benefits to having a brain that has been around for a while. It’s a discussion that’s well overdue, whether or not it’s an election year.

Aging Has Some Cognitive Perks, for Real

As we accumulate years, we also accumulate perspective, continually organize new information, and may even develop better judgment. “You have life experience that leads to wisdom and gut intuition of what’s a right decision,” says Chip Conley, a cofounder of the Modern Elder Academy and author of Wisdom at Work: The Making of a Modern Elder.

It’s a concept known as crystallized intelligence, through which people pull from a stored base of knowledge. “It’s important because you have better pattern recognition and can see complex issues more clearly,” says Conley. So you get what’s going on and can solve problems at a faster pace.

Plus, over the years, you keep cultivating new connections between brain cells. This is known as neuroplasticity, which promotes the brain’s ability to adapt to new ideas and circumstances. And we can continue to boost cognitive reserve—or brain capacity—to slow the development of symptoms if your brain health does decline.

Venerated elders who work effectively in top positions can also regulate their emotions better—essential when you have to console hurricane victims and then immediately respond to a geopolitical crisis in a single afternoon. “The raw processing power of youth isn’t the end-all and be-all,” says Adam Felts, a researcher with the AgeLab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Aging Ignites Certain Biases

Recognizing the benefits of aging is critical, some experts say, to shaping a more honest discussion about what society can expect—even value—from older leaders.

Any perceived decline, such as Biden stumbling or flubbing his words or Trump forgetting key historical facts (e.g., saying we’re on the verge of “World War II”), isn’t an accurate reflection of cognitive capacity. “The way in which we’re having this conversation about how old we want our leaders to be isn’t being done in good faith,” says Felts. Instead, we need to distinguish between legitimate concerns about someone’s lucidity and ageist stereotypes.

“No one is asking for Warren Buffett to leave his post at 93,” says Conley. “We have lots of antiaging messages, but I want to talk about pro-aging messages. People are living longer and being more vital and doing things we couldn’t have imagined before.” In other words, we should stop obsessing about someone’s age—and the way they walk or talk—and focus on their mindset. “Are they open and curious about new experiences and ideas? That’s my clue they’re in great shape cognitively,” Conley continues. “It means they’re creating new connections between synapses and keeping themselves youthful and vital.”

Yet due to the fact that the current Congress is one of the oldest ever, there is an ever-present question in public forums about subjecting politicians to upper age limits or requiring them to prove their brain fitness. Some people say everyone should undergo routine cognitive screenings at age 70.

To be clear, 70 isn’t a threshold for cognitive deficits. It may just be a useful starting point for a screening recommendation. Dr. Mesulam emphasizes that people’s brains age at different rates. “If you think of a group of five-year-olds, they are likely to share similar height, vocabulary, and cognitive ability,” he says. “But if you collect five 85-year-olds, they will all be very different.” One or two will have Alzheimer’s, considering that about one third of the population may develop the disease by this age. One might be a SuperAger—the term used for an 80-plus superstar who has the mental fitness of someone 30 years younger. And the others will be in between, their fate determined by a stew of genetics, environmental influences, lifestyle choices, and the vicissitudes of life.

Right now the most common first-step cognitive screenings are done in a doctor’s office and involve verbal and drawing tests. In the future, blood tests, brain scans, and speech-pattern-recognition software may more accurately detect cognitive decline.

Even in the case of impairment, there is hope: New Alzheimer’s therapies show promise, and the surging interest in longevity medicine has intensified research on aging proteins that could be targeted with drugs.

Surprising Ways to Improve “Brain Span”

So yes, there’s exciting research on drugs to change your cognitive health. But other new science is focusing on simpler things that are within your control: the importance of social connection on long-term brain health, and the impact of your perspective on aging.

Neuroscientist Emily Rogalski, Ph.D., who leads the multi-site SuperAgers Research Initiative at the University of Chicago, is taking a deep dive into how social connection might be part of the healthier-brain/longer-life equation. It didn’t take a pandemic to point out the flip side of friendship: Feeling isolated leads to increased inflammation, blood pressure, and clotting.

But it’s been hard to quantify just what kind of engagement matters most for brain health: Is it an hour-long phone call with a close friend or several rounds of chitchat throughout the day with a coworker, barista, or cashier? So Rogalski’s team, in collaboration with Western University, recently launched a study that gives chest, ankle, and wrist sensors to more than 500 SuperAgers in order to measure their sleep, physical activity, and social interaction. “Before, we had primarily subjective data about life activities and sleep,” she says. Now the devices’ data can be integrated with measures of brain structure and function. The hope is for it to yield evidence for exactly how we should socialize to maximize cognitive benefit.

Other research suggests the antiaging power of your own beliefs. A famous Yale University study from 2002 found that people who had positive views about aging lived more than seven years longer on average than those with less positive opinions about the topic. More recently, a research panel of 75 people over age 85, managed by Taylor Patskanick, a researcher at the MIT AgeLab, revealed similar findings. “This group is redefining our expectations on how we age,” she says. “They’re doing well in older age, and they want people to know it’s not all bad.” The panelists, several of whom are Holocaust survivors, are proud of their resilience in having lived this long and overcome challenges. They also see cognitive decline as something that happens to others.

As people consider third and fourth and fifth careers (or disregard the traditional retirement age altogether), we as a society are grappling more and more with our expectations for aging. It may be time to leave behind the idea of categorizing people by how many years they’ve lived. And time to stop trying to send off those of a certain age and instead look at how they’re leading the way.

3 Ways to Keep Your Brain Young

1) Diversify your workout

“A combination of aerobic activity and strength training seems to be the magic mix for the brain,” says Audrey K. Chun, M.D., a geriatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Movement that pushes up your heart rate gets blood to your brain and lowers brain-damaging high blood pressure. Resistance training is critical, too: It circulates small proteins through the body and brain that are linked to the growth of new neural cells and the brain’s ability to adapt and change.

2) Continue learning

More education is linked to a lower risk of Alzheimer’s, and the theory is that there’s more “cognitive reserve”—even if you lose a little, you’re still functioning at a higher level, explains Dr. Chun. She says that maintaining function doesn’t necessarily relate to how many years you went to school; being a curious, lifelong learner is also likely protective.

3) Say cheers with an N/A beer

Remember when drinking a few glasses of red wine was thought to be good for your health? A 2021 study of 25,000-plus drinkers in England found a connection between even moderate consumption of any kind of alcohol and brain shrinkage. It’s clear now that “alcohol is a neurotoxin,” says Dr. Chun. The new rec: Limit yourself to one drink a day or go for nonalcoholic brews, spirits, and wines only.

This story originally appeared in the March/April 2024 issue of Men's Health.

You Might Also Like