8 wild stories about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the 'father of the atomic bomb'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

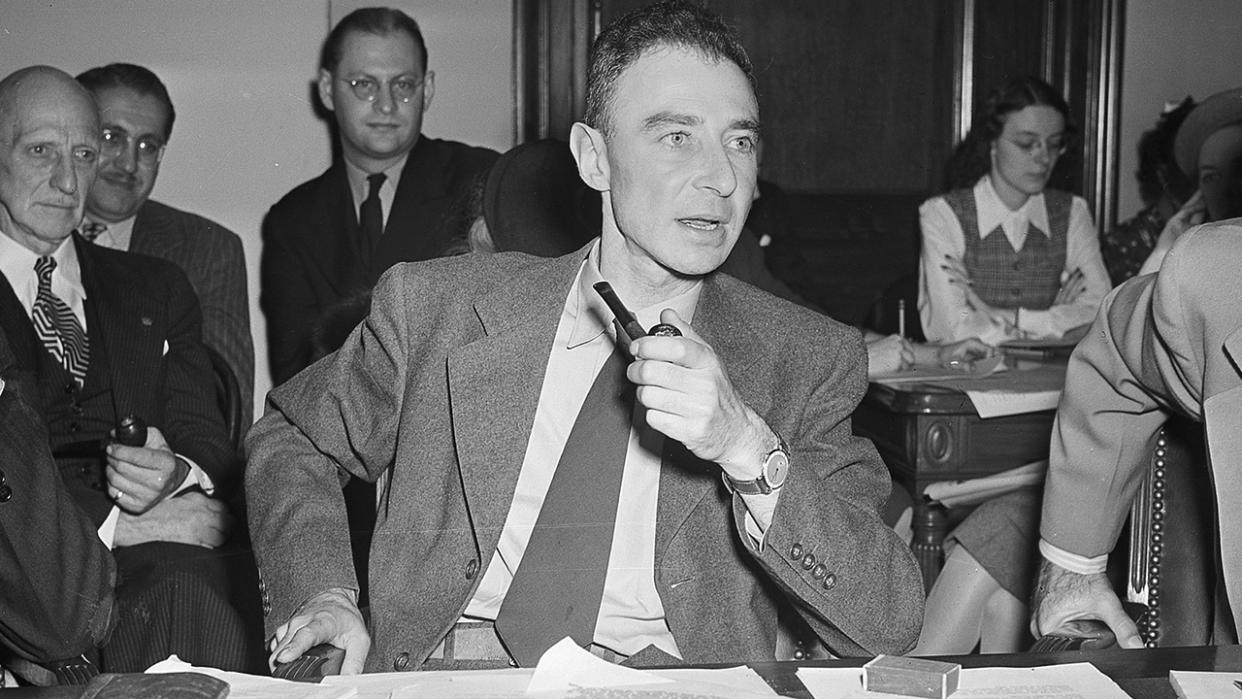

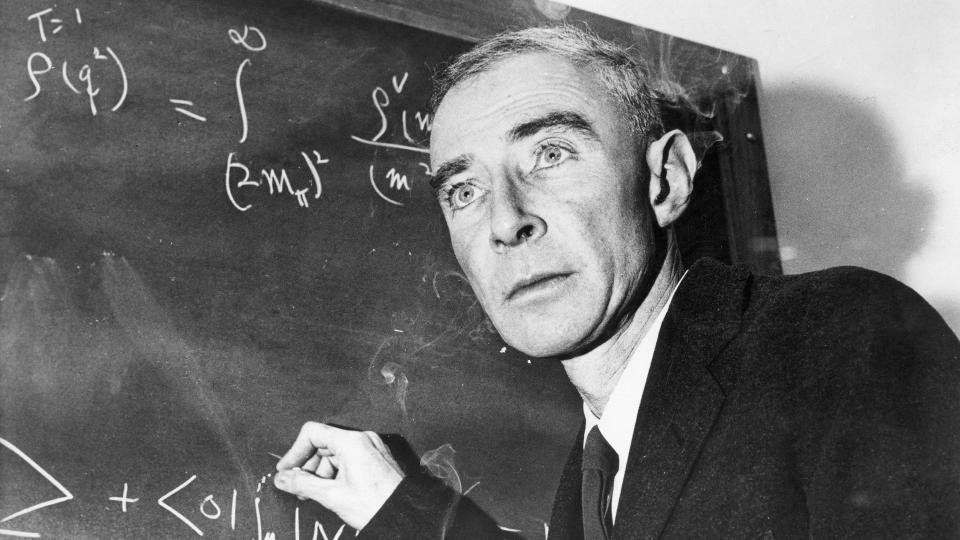

J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904 -1967) is infamous for spearheading the development of the world's first atomic bomb — but the physicist's life was far from boring outside the lab. Here are eight intriguing stories about Oppenheimer, drawn from the biography "American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer" (Knopf, 2005), by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.

Related: Read Live Science's exclusive interview with biographer Kai Bird for more wild Oppenheimer stories

1. He was the first to propose the existence of black holes

Oppenheimer was a tireless dilettante and loved to pursue his intellectual curiosity in any direction it took him.

After having been introduced to astrophysics by his friend Richard Tolman, Oppenheimer began publishing papers on theorized, yet-to-be-discovered cosmic objects. These papers included calculations of the properties of white dwarfs (the dense glowing embers of dead stars) and the theoretical mass limit of neutron stars (the incredibly dense husks of exploded stars).

Perhaps his most stunning astrophysical prediction came in 1939, when Oppenheimer co-wrote (with his then-student Hartland Snyder) "On Continued Gravitational Contraction." The paper predicted that, far in the depths of space, there should exist "dying stars whose gravitational pull exceeded their energy production."

The article received little attention at the time but was later rediscovered by physicists who realized that Oppenheimer had foreseen the existence of black holes.

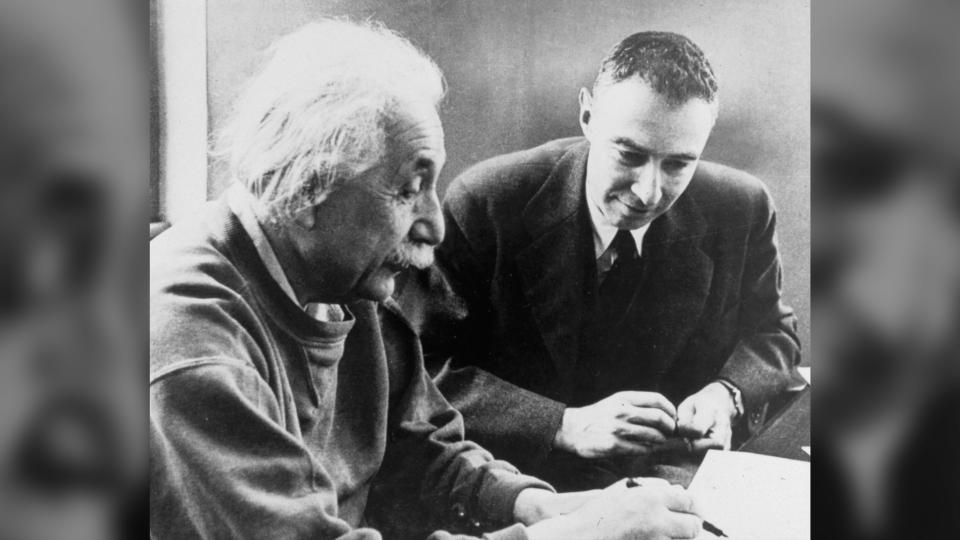

2. Einstein called him a fool

Oppenheimer's stunning intellect and vast learning didn't always overcome his emotional immaturity and political naivety.

One such instance was a disagreement he had with Albert Einstein during the height of the McCarthy Red Scare. After bumping into Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, he spoke with his colleague about the growing efforts to revoke his security clearance.

Einstein counseled his colleague that he needn't submit himself to a grueling investigation and trial by the Atomic Energy Commission; he could just walk away.

But Oppenheimer replied that he would do more good from inside the Washington establishment than from the outside, and that he had decided to stay and fight. It was a battle Oppenheimer would lose, and the defeat marked him for the rest of his life.

Einstein walked to his office and, nodding at Oppenheimer, said to his secretary, "There goes a narr [Yiddish for 'fool']."

3. He may have tried to poison his professor with an apple

Oppenheimer faced trying times while studying for his doctorate in physics at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England. His intense emotional issues and feelings of growing isolation drove him into a period of deep depression.

Oppenheimer's adviser at Cambridge was Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, an intelligent and gifted experimental physicist whom Oppenheimer envied. Despite Oppenheimer's renowned impracticality, Blackett pushed his student into laboratory work.

Oppenheimer's constant failures in the lab and his inability to win Blackett's approval made him intensely anxious. Consumed by his jealousy, Oppenheimer may have gone to extreme lengths. A longtime friend, Francis Fergusson, claimed that Oppenheimer once admitted that he laced an apple with noxious chemicals and left it enticingly on Blackett's desk.

However, there is no evidence of this incident beyond Fergusson's claims — and Oppenheimer's grandson, Charles Oppenheimer, disputes that this ever happened. But if there was a poisoned apple, Blackett didn't eat it. Oppenheimer is said to have faced expulsion from the school and possible criminal charges, before his father intervened and negotiated that his son instead be put on academic probation.

4. President Truman called him a crybaby

Oppenheimer was very persuasive in relaxed settings, but he had a terrible tendency to crack under pressure.

Just two months after the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer met with President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office to discuss his concerns about a possible future nuclear war with the USSR. Truman brushed off Oppenheimer's worries, assuring the physicist that the Soviets would never be able to develop an atomic bomb.

Maddened by the president's ignorance, Oppenheimer wrung his hands and said in a low voice, "Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands."

Truman was enraged by this remark, and promptly ended the meeting.

"Blood on his hands, dammit — he hasn't half as much blood on his hands as I have," Truman said. "You just don't go around bellyaching about it." Truman later told his secretary of state, Dean Acheson, "I don't want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again."

Truman regularly returned to the subject of the Oppenheimer meeting with Acheson, writing in 1946 that the father of the atomic bomb was a "cry-baby scientist" who came to "my office some five or six months ago and spent most of his time wringing his hands and telling me they had blood on them because of the discovery of atomic energy."

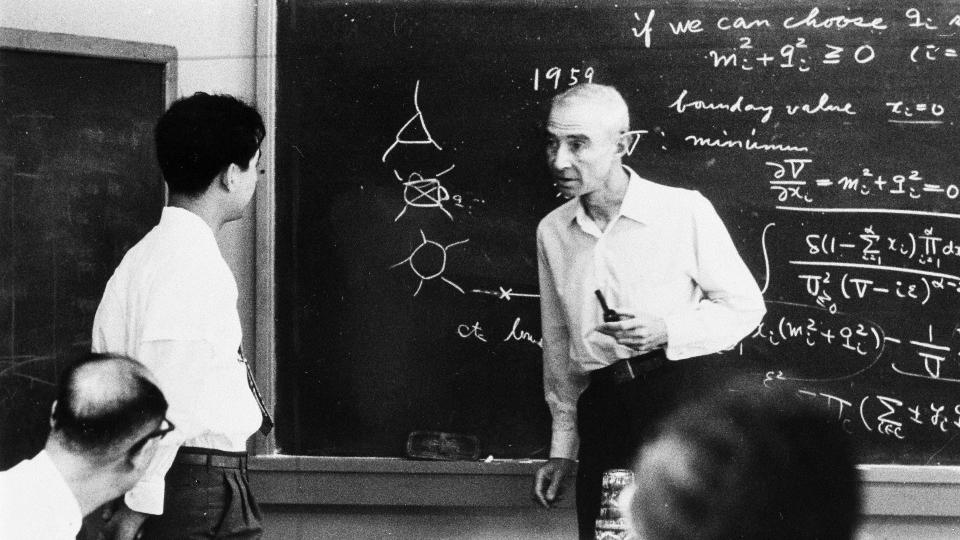

5. His students were obsessed with him

Oppenheimer was a verbal physicist by temperament. He didn't rely solely on math to understand the world; he also reached for useful ways to describe it with words. His rhetorical felicity, and his erudition on topics far outside of physics, made him a captivating speaker.

Oppenheimer was so gifted at crafting beautiful sentences — often on the fly — that he enraptured the students he lectured. Some of these students became so obsessed with Oppenheimer that they began to dress and act like him — donning his gray suit and ungainly black shoes, chain-smoking his favorite Chesterfield cigarettes and mimicking his peculiar mannerisms.

The starstruck students were nicknamed the "nim nim boys" because they carefully imitated Oppenheimer's eccentric "nim nim" humming.

6. He was a passionate student of the humanities and could speak six languages, including ancient Sanskrit

Oppenheimer loved an intellectual challenge and relished any opportunity to demonstrate his prodigious ability to soak up information. He spoke six languages: Greek, Latin, French, German, Dutch (which he learned in six weeks to deliver a lecture in the Netherlands) and the ancient Indian language of Sanskrit.

Oppenheimer also read a lot of books outside of his field. He told friends that he had read all three volumes of Karl Marx's "Das Kapital" cover to cover on a three-day train trip to New York, that he had similarly devoured Marcel Proust's "A La Recherche du Temps Perdu" ("In Search of Lost Time") to cure his depression while on vacation in Corsica, and that he had learned Sanskrit so he could read the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita.

Oppenheimer's close reading of the Gita gave him his most famous quote. In a 1965 NBC interview, he recalled his thoughts upon seeing the mushroom cloud from the first successful atomic bomb test:

"We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, 'Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.' I suppose we all thought that one way or another."

7. At age 12, he was mistaken for a professional geologist and was invited to give a lecture at the New York Mineralogy Club

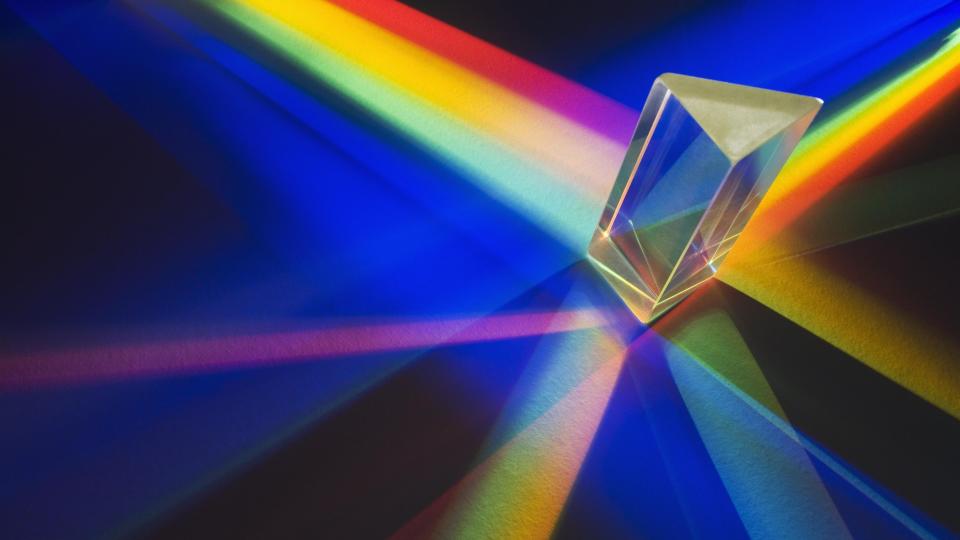

From age 7, Oppenheimer became fascinated with crystals because of their structures and interactions with polarized light. He became a fanatical mineral collector and used his family typewriter to begin lengthy and detailed correspondences with local geologists.

Unaware that they were writing to a 12-year-old, one geologist invited Oppenheimer to deliver a lecture at the New York Mineralogy Club. Oppenheimer wanted his dad to explain to the club that his son was only 12, but his father was tickled by the incident and urged him to go.

The room of surprised geologists burst into laughter at the revelation that the boy was their mystery correspondent, but they soon provided him with a wooden box so he could reach the lectern. Oppenheimer delivered his speech and was met with applause.

8. He code-named the first atomic bomb test in honor of his dead mistress

Oppenheimer first met Jean Tatlock in 1936, and began a passionate romance that continued throughout his marriage to Katherine Puening and ended with Tatlock's death in 1944. When Tatlock and Oppenheimer met, Tatlock was an active member of the Communist Party and persuaded Oppenheimer to allay his concerns about the poverty he was witnessing during the Great Depression by donating to the party.

Oppenheimer's reputation as a communist sympathizer soon attracted the attention of the FBI, whose agents began to follow and wiretap him.

In 1944, Tatlock was found dead in her apartment from an apparent drug overdose. She had suffered for much of her life with intense bouts of depression and left an unsigned note, so her death was ruled a suicide. Nonetheless, conspiracy theories — some alleged by her brother — about intelligence agencies' supposed involvement in her death abounded.

Tatlock introduced Oppenheimer to the poems of John Donne, whose work she loved. He drew from Donne's poem "Batter my heart, three-person'd God …" when he assigned the code name "Trinity" to the first test of an atomic bomb.

The FBI's monitoring of Oppenheimer and Tatlock came back to bite him during his trial at the Atomic Energy Commission's 1954 security hearing, where his affair was exposed and used to allege that he had still held communist sympathies late into World War II. The trial, which resulted in the revoking of Oppenheimer's security clearance, hounded him from public life — making him one of the most prominent victims of McCarthyism.