A 6-Year-Old Homeless Girl Named Daisy Moved This Midwestern Woman to Action

Oprah Daily’s series Good People Doing Great Things highlights everyday heroes who see a need and are stepping up to help. Want to celebrate a local leader who’s making an impact? Email us at OprahDailyStoryIdeas@hearst.com and we may feature them in an upcoming column.

It was about 107 degrees in Puerto Cortés, Honduras, on the day in 2001 that changed Rebecca Welsh’s life. She had floated into the northern port city a few days earlier on a Mercy Ship, a charity hospital that travels by sea to provide free healthcare in developing countries. On that sweltering afternoon, Welsh was on a break from her volunteer duties and had just ordered a drink at a liquado stand when she felt a tug on her shirt and looked down into the eyes of a 6-year-old child. Her name was Daisy.

Daisy had no shoes but numerous infected cuts on her legs and feet, bald spots on her head—chicken lice and poor nutrition had caused her hair to fall out—and leathery skin from too much sun. She seemed scared and apprehensive but had mustered up the courage to ask Welsh, whose warmth and kindness is palpable, if she could have her drink.

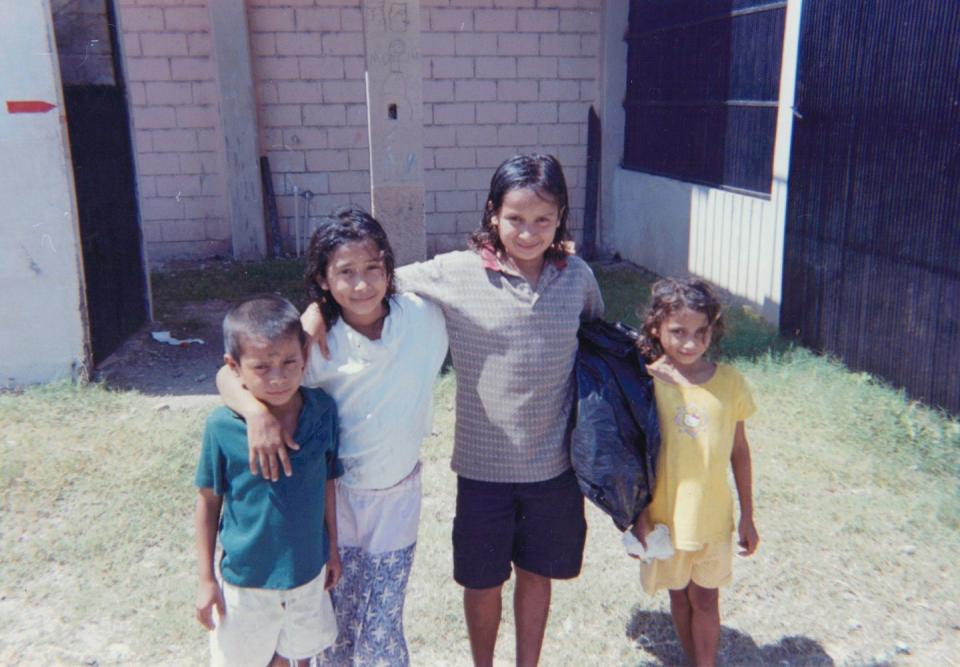

Towering over Daisy’s small frame, Welsh began urgently scanning the street for the child’s mother when she spotted a group of street kids nearby waiting for their youngest friend. She asked the oldest, an 11-year-old girl, what was going on. The kids were homeless, sleeping on cardboard boxes in alleyways. “I had never witnessed human suffering in that manner, tangible human suffering everywhere in front of your face,” says Welsh. “I was completely heartbroken by it.”

That night, Welsh couldn’t sleep. She felt ashamed of the evidence of better fortune around her on the ship—plenty of food and beverages, and air conditioning. The next day, she started visiting and volunteering at the local orphanages, but none had space to accommodate Daisy and her family of friends.

Welsh visited Daisy and her crew as often as possible, providing them with as many supplies as she could collect, including shoes, which they wanted above all else because of the difficulty of treading the boiling, trash-strewn streets without them. But six months later, the time came for Welsh’s ship to set sail, and it left her raw.

“The last time I saw her before I left, I knew it would be the last,” Welsh says of Daisy. “I couldn’t do anything for her. I couldn’t get her into an orphanage. It ate at me forever, and I had terrible dreams about her all the time. She was a beautiful flower that was never watered,” says Welsh, pointing out the irony of having such a soft name and such hard circumstances. “She never got to actually bloom.” But her memory is the reason so many others have: With Daisy both haunting and guiding her, Welsh returned to the United States cradling the determination to help youths in similar circumstances.

After landing back in Kansas City, Missouri, in 2002, Welsh ran a martial arts school of 250 students, where she taught life skills alongside self-defense. During a unit on compassion, she told her young pupils about Daisy, and they were inspired to take action on behalf of kids like her. “Why don’t we do something?” they asked. That prompted the first “board break-a-thon,” which Welsh describes as “karate chopping as many boards as you can in 30 seconds.” They got sponsors and raised an impressive $5,000.

With that initial influx of cash, Welsh boarded a plane for San Diego and crossed the border into Tijuana, Mexico, her grandmother's native land, to establish partnerships with local orphanages. “I wanted to be in a place that was easily accessible for volunteers to travel and serve,“ she says. When she visited various locations in Mexico, she says, “I started asking questions like ‘How many kids do you support? Where does your funding come from? What are the standards of the home? How can we help?’"

Returning home, Welsh reached out to several school districts (local and nationwide) to team up on more break-a-thon fundraisers, which generated $40,000 that first year and then over the next three years a staggering $250,000.

Welsh took those funds to Tuni, India where she teamed up with local organizations after devastating tsunami in 2004 leaving more than 250,000 people dead and hundreds of orphans in the streets and provided longterm funding and resources to shelter of 40 kids. “Today, some of those kids have amazing stories, like going to engineering or nursing school.” she says. "In the early 2000's, I wanted to put my efforts overseas because I knew how far I could stretch the dollar to help as many children as possible and there was such grave need," she remembers. "At that time, I wasn't yet aware of the extreme forms of suffering from poverty, abuse, and parental neglect in the United States."

Youth homelessness is an enduring problem that is sometimes hard to quantify in the United States. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Homeless Education reported 1.28 million homeless students in the 2019-2020 school year, while the Department of Housing and Urban Development identified only 106,364 homeless children under 18 and 45,243 homeless young adults, 18 to 24, in a 2020 report.

According to reporting in NPR and The New York Times, the wide gap is due in part to HUD’s narrow definition of who counts as homeless—people living in shelters, transitional housing, or on the street—missing the “hidden homeless” who couch surf with various family and friends or live with families in cars or are squatting in abandoned buildings.

Welsh adds: “The problem with the statistics on youth homelessness is that teenagers don’t want to say that they’re homeless. There are so many kids that are flying under the radar.” In fact, a study in 2017 showed that 4.2 million kids experience some form of homelessness each year—and African Americans are 82 percent more likely to experience it. Globally, homelessness in both developed and developing countries, affecting all age ranges, has seen an “alarming rise” over the past 10 years, according to the United Nations, which announced its first-ever resolution on homelessness in 2020, and youths, they report, are the most vulnerable to becoming homeless.

But back in 2005, after returning from India, Welsh reached out to local shelters in Kansas City, MO because she wanted to understand the issues in her own backyard. "Internationally, you'll see a homeless kid starving on the street. Domestically, they may have food and shelter but they are starved for support and affection. The recurring refrain I heard from leaders at local youth shelters in Kansas City is that the kids age out of the shelters and then have had no place to go and no resources," she remembers. That's when she officially founded HALO (which stands for Helping Art Liberate Orphans), a nonprofit whose mission is to create homes, healing through the arts, and education for teens aged 16-21 and their dependents.

A foundational experience in Honduras informs the art component of the organization. The 42-year-old mother of three recalls bringing a collection of coloring books, crayons, paints, and papers to a local orphanage. She says she’d say to the kids, “‘Let’s do a painting of yourself. Let’s do a painting of what you want to look like when you grow up. Let’s do a painting of someone who you know cares for you.’ It just cracked open everything for the caretakers with the kids. Art is a great tool for healing.”

The housing piece, Welsh explains, isn’t just about providing basic shelter; it offers something far warmer and richer than that—the foundation of a family. Currently, HALO operates six HALO programs in Kansas City and Jefferson City, MO with plans to expand into New York City, Nashville and St. Louis in the coming years. The organization also runs 11 facilities, which include homes and educational centers, in 5 countries (India, Kenya, Mexico, Uganda and the United States) serving over 3,000 youths with 300 committed volunteers.

All HALO homes, domestically and internationally, are part of a learning center that serves members of the entire community. A young person can come in and learn a trade like becoming a tailor or a mechanic, but also life skills like opening a bank account, using public transportation, and interviewing for a job. “We do anything that a family would do for them—teaching them how to make their bed or showing up for their graduations,” Welsh says.

But Welsh has an even greater vision. “There should be a HALO home in every community that needs one, just like there's a food bank or a community health center,” she says. Help from monthly donations and volunteers can inch her toward her dream, but to really make a dent in the growing youth homeless crisis, she is seeking major philanthropic partners to infuse the current system with desperately needed resources, adding pointedly, “We cannot as a society expect for them to pull themselves up by their bootstraps if they don’t even own a pair of boots.”

One of the major challenges she encountered when trying to start HALO 17 years ago, in fact, was the poor opinion people held of the “bootless” population she sought to serve: “Well-respected members of our community felt the kids were a ‘lost cause,’” she remembers. “I was like, no, all they need is someone to come into their lives and say, ‘You can do this, and we’ve got your back.’”

The way Welsh sees it, fifty percent of her job is helping people realize that “we’re all here for a reason and we all have something to give—and it’s a gift to be able to give it,” she says. That includes convincing potential volunteers that their time is an impactful contribution and that whatever skill they have is worthy. “Looming, mowing the grass, making potato soup, or bringing over a casserole—all skills are needed and welcome."

Make a difference by donating or volunteering your time at HaloWorldwide.org.

Follow the organization on Instagram @haloempowersyouth.

You Might Also Like