A 6-Year-Old Boy’s Killing Stunned America. What It Did to His Parents Is Something Else Entirely.

They told him over the phone, about an hour after it happened. Odai Alfayoumi still looked stunned as he sat across from me, with some sweets and coffees on the table. Pictures of a young boy surrounded us on the shelves. Alfayoumi’s fingers were folded, and he mostly looked away while we talked. When he did look me in the eyes, I could see that his own eyes were red, as if he’d just cried before I arrived.

“That Saturday, as I was getting ready to go to work, I received a call from the sheriff,” he said. “They asked me, ‘Are you Odai Alfayoumi?’ I said yes. They asked, ‘Are you Wadee Alfayoumi’s father?’ I said yes. Then they told me Wadee was murdered.”

Wadee was 6 years old. It didn’t compute. Who would kill a 6-year-old?

Alfayoumi hadn’t been talking to reporters. He’d made a few public appearances since his son was murdered, but he didn’t speak much, and when he did, he spoke in Arabic. I could see why.

He told me he keeps thinking about that call. “You shouldn’t inform someone of such news in this way,” he said. “It was a shock for me. I couldn’t believe it. He was telling me, and I couldn’t grasp what he was saying,” he said. “Finally, I asked him, ‘Where is the boy?’ He said, ‘He’s dead.’ I said, ‘Where is he now?’ He said if I had time, I could go to the police station so they can explain. I went, and they explained that he was stabbed.”

They gave him bits of information piece by piece. By that night, it was becoming national news out of Chicago that his son had been killed, and the child’s mother, his ex-wife, was hospitalized. “I cried nonstop until that evening,” Odai said. “He left this world and he took our hearts with him.”

As he learned more about the killing, he realized he knew the man accused. The man owned the house where his ex-wife and son lived; he lived just outside their door. The man had a good relationship with them, or so he thought. He would even sometimes greet them with the standard Arabic greeting, as-salamu alaykum. Now the man was alleged to have stabbed his son 26 times, until he died. He wanted, the police said, to kill Palestinians.

Alfayoumi never intended to live in America. He is from Jordan, where he was a successful interior designer. But when he visited Chicago in 2015, at 26, he was convinced to stay.

During his visit, he met a young Palestinian in a Facebook group for Arab Americans in the Chicago area. He says she encouraged him to stay in the States. So he did. Within a year, they had married, and had a baby boy, Wadee. “Life wasn’t easy here. I rushed my decision to stay in America. I was a tourist,” he told me. “I was supposed to stay a short period and go back home. It is destiny, nevertheless. My story is predestined.”

The relationship didn’t last. Just two months after his son was born, Odai’s wife asked for a divorce, saying she was unhappy. Though the divorce process took three or four years, he said they maintained a strong friendship rooted in mutual love for their son. The custody was divided in a way that left Wadee with Odai only two days out of every two weeks.

“His mother usually brought him to me at 9 in the morning,” he remembered. “I would be sitting here on the chair looking outside the window to see him when he arrives.” The long periods in between visits took a toll: “Longing increases. When I drive him back to his mother on Sunday, I feel like he’s taking my heart with him. You become like a charger; today you miss him a bit, tomorrow you miss him more, and so on. By the time of the next visitation, I am totally out of charge; I must see him. And as soon as I see him, even for only five minutes, I feel much better.”

Alfayoumi stayed in Chicago in part because he wanted his son to have more opportunities later in life. “In Jordan, it wouldn’t be surprising to find that your taxi driver has earned a high academic degree. He might be a doctor. There are many doctors, but there are few jobs and low salaries,” he said. “My life perspectives have changed drastically. His future is what made me stay in America when I came as a tourist.”

Having a son named Wadee had been Alfayoumi’s dream since he was a child. His nickname growing up was Abu Wadee (“father of Wadee”), because he wished his name had been Wadee instead of Odai. Rather than change it, he committed to giving that name to a son if he were to one day have one. And when he finally did, he says, it felt like fulfilling his lifelong dream. “It is killing me knowing that my dream has come to an end,” he said.

I got the sense that Alfayoumi was still living in some kind of in-between—a dream state where he hadn’t yet processed exactly what had happened. His olive-green eyes were haloed by dark circles of exhaustion. In his home, he held back tears as he scrolled through his phone, showing me the last photos he took of his son Wadee, including one of him wearing a sparkling blue birthday hat on his 6th birthday, just days before the knife attack. “He loved to pray,” Odai said, as he showed me one of his son kneeling on an adult-sized prayer rug that showed just how small he was.

“I am 37 years old. I’ll be 47 in 10 years. My son would have been 17 years old,” he said. “The whole dream has ended.”

It’s even more surreal that he knows the man who killed his son. When Wadee and his mother moved into the apartment where he would be killed, Odai went to inspect it and met the landlord, Joseph Czuba. “He’s the one who let me in and showed me around. I didn’t like the house because it’s hard to get in the driveway. My biggest fear was she gets into an accident on her way in or out, or the boy runs out into the street,” he said. He said the landlord looked rough and disheveled, but he came to feel at ease with him: “He would collect scrap wood and create a table or chair for the boy to play with. He made a treehouse and created a swing between two trees out of strings and ropes. He had a swimming pool, a stage for performances. He put in tremendous effort into these projects and when I asked him why, he said, ‘for the boy to play and be happy.’ ”

“I only saw him when I came to pick up or drop off Wadee. I’d ask him if the boy was keeping him up or bothering him, and he would say, ‘No, it’s the opposite. I take him around the house. We play together,’ ” he recalled. Now that he knows what happened in that house, he cannot comprehend these interactions.

Odai can’t get one detail of that day out of his head. “Imagine a child gets stabbed 26 times? This is the kind of question that has no answer. Which one killed him? The first, second, 10th, 12th, or the 17th? Which one ended his life? How did he feel being stabbed by someone who he might have thought was playing with him?”

Hanan Shaheen, Wadee’s mother, has also shied away from the press. This is completely understandable: She too was stabbed repeatedly, and had to spend a week in the hospital due to her wounds. She couldn’t go back home after her release—the carnage remained—so she lived out of a hotel for several weeks before finding a new apartment in a nearby town. I was told not to expect to meet her.

But while I was in Chicago, people close to the family put us in touch. When I met her, I was taken aback: She was all smiles.

“How beautiful it was to have these six years and eight days filled with prayer and kisses and warm hugs and a happy creative boy that was so smart and singing, whose friends knew his name before they learned their name. He was an angel we had for six years and eight days,” she said with a bright smile. We talked about how her son mimicked the way she prayed, mouthing syllables to copy the way she quietly recited Quran. “When he was young, he would bring a scarf and skirt!” she said, with clear delight.

Her new apartment was still only sparsely furnished, with bare walls that echoed and emphasized the sound of her laughter. We both laughed as she recalled how Wadee would dress himself. “He would sometimes put them on backwards! He would say, ‘Let’s go to the park. I’m ready.’ I’m like, ‘You’re wearing your clothes on the wrong side.’ They would laugh at us at the park,” she said. “And now he is a bird of heaven.”

Hanan served Arabic desserts on her coffee table, an assortment of bite-sized baklava and Bird’s Nest Kunafa, which I had picked up from a Palestinian dessert shop. I asked her why she said yes to my interview request when she had turned down many others. “I’m not satisfied with my face, and these bandages,” she said, pointing to the several small bandages on her lip and chin, and scars on her face. “I was hesitant to do that first press conference. It felt like many, many people wanted to see me. Many, many people are asking, waiting for me to report that I’m still good. So I said only one time, let’s do it, to show the people I am good.”

As the father of two young kids myself, I wondered if this was how Hanan’s grief had manifested: the beaming conversation, the obvious joy in her memories of her child, her focus on the present and refusal to dwell on what happened. When I gently asked what she remembered from that day, she declined to discuss it, but a representative for her provided a written timeline.

That statement says Wadee and Hanan lived in Czuba’s house for two years, renting two rooms. They shared a kitchen and a living room, which they needed to pass through to access their “private space,” including two small bedrooms, a kitchenette, and a bathroom. They interacted every day, and had good relationships. Wadee would refer to Czuba and his wife as Grandpa and Grandma.

Everything changed after the start of the war in Gaza in October. According to the family’s lawyer, it started Saturday morning with Wadee undressed and about to take a shower, and Czuba knocking on the door in his living room leading to his tenants’ space. Hanan answered, and was surprised to find Czuba yelling at her, demanding to know why she wasn’t doing anything to “stop the war” in Gaza. She told him that she prays for peace. Then, the statement said, he physically attacked her. She was stabbed 12 times with a 12-inch knife with a 7-inch serrated blade. She took blows to her chest, torso, and limbs. Cuts to her face were still visible.

The statement said Hanan fought back, scratching Czuba’s forehead. She pleaded with him to stop, telling Czuba, “Let’s go to the hospital.” But, the statement says, he continued to fight her. After, she laid immobilized on the ground, then pulled herself up, locked the door, and quietly called 911 from her bathroom so as not to alert Czuba. But unbeknownst to her, he had already broken back into the space she was renting and stabbed her son 26 times. She didn’t hear any crying or screaming. When she came outside the bathroom, the police said she found her son on the ground with the knife still lodged in his abdomen.

Police arrived at the scene quickly and found Czuba sitting on the ground outside the house.

Paramedics transported everyone to the hospital. At this point, Wadee was still alive but in critical condition. While Hanan was being treated, she gave the nurse Czuba’s wife’s phone number, and asked her to call her to explain what happened so that she wouldn’t come home to the bloody scene and be surprised.

She explained to the nurse how to take care of her son in case she didn’t survive. But soon after that, a doctor entered the room, put his hand on hers, and told her, “Your son did not make it.”

By Sunday afternoon, just a day later, the sheriff’s office released a statement that announced Czuba was charged with first-degree murder, attempted murder, battery, and hate crime charges. (Czuba has pleaded not guilty.)

Hanan said she was grateful to the police, but declined to speak any more about it. Instead, she told me of her son’s love of cars, sports, and school, and her life before America. She said she was born and raised in Beitunia, a village outside Ramallah, in the West Bank, to a huge family with nine siblings on an idyllic farm. Her family grew peaches, grapes, figs, tomatoes, and olives, and they had some chickens and goats, too. Neighbors came to the farm to buy from her family, and that was enough to sustain them. “There were no houses, only a few in a large area, and you could see only trees,” she said. “It was beautiful nature; we were surrounded by green.”

After finishing high school down the road from her family’s farm, Hanan became a kindergarten teacher. Her sisters married young, but when people came to ask for her hand, her parents turned them away. “I can’t even remember the number of people who came. My mom and dad told them I was young and they didn’t want to say goodbye to me so early, so they would say ‘Sorry,’ ” she said. When she turned 20, a Palestinian American suitor from Chicago got her family’s blessing. “I saw my parents smiling, and I thought, ‘Why not give it a try?’ ”

She hadn’t considered coming to America before. She was happy in her village, but she soon relocated to Chicago in 2012. And within two years, she had two boys, Ismail and Mohamed. That marriage didn’t last long. After four years, she asked for a divorce. “The system of this life, with the dad working hard, staying out most of the time, the way we handled this marriage made it impossible to continue it,” she said. The boys went to live with their father and she sees them on the weekends.

It was during this process that she met Odai on Facebook and moved quickly into that marriage, where she would have Wadee and then get divorced again. “There were no romantic moments or things. We couldn’t continue at all in this marriage. I felt it wasn’t written for us to continue as wife and husband. So I filed for divorce just three months after delivering Wadee, because I couldn’t continue,” she said. It was then, she says, that she could finally focus on living her own life. “And then I began my life as a single mom. Not just a single mom, but I would be me. Not a happy wife; happy Hanan. I wanted to live my own life journey, and that’s it. I wanted to continue as Hanan,” she said. “This time, I took my son with me. I said I would keep my son, and you could have visitation. We continued this way for six years.”

She found work as a caregiver for senior citizens, and moved around a lot, always looking for more affordable living situations. It was a real estate agent she was speaking to who suggested the rooms for rent at his brother Joseph Czuba’s home.

She felt the place was nice enough, but was much more attracted to the price tag: $300 a month. She had mixed feelings about her new landlord/housemate. “I lived with him for two years. He did talk politics a little. I could hear him. He’s an angry man. But I didn’t expect he would judge me for these things happening overseas,” she said.

“It was like the landlord changed. He just went nuts,” she said. “He was listening to the news and judging me for what he was hearing. He was like, ‘I told you about the war between your people, the Muslims and Israel, and you’re not doing anything about it.’ He wanted me to do something about it?” she asked. She laughed as she told me this.

She couldn’t stop laughing.

Odai lives in Bridgeview, a moderately sized village 45 minutes outside of Chicago that’s known locally as Little Palestine. It’s immediately noticeable on the main strip, South Harlem Drive, with its various Arabic-language storefronts, some of which make direct reference to Palestine.

“Here, you go back to 2004, 2005, plazas here were like 50 percent occupancy. Now they’re full occupancy, with a variety of restaurants, sweets stores, Arabian clothes, Arabian hijabs, and more,” said Maher Khattab, an ordinance inspector in the village. “We are the majority in this precinct.”

Syrian by birth, with partial Palestinian ancestry, Khattab recently celebrated 30 years of living in the area, first arriving in Chicago when he was 25. He had hoped to one day go back to raise his family in Damascus, but made his roots in Bridgeview permanent after the Syrian civil war made it impossible to go back home.

He said the Arab diaspora is attracted by the Islamic schools and established mosques in the area. He watched the community develop from a small, almost entirely white town into what it is today. He remembers back in 1993, when the Mosque Foundation was just one small room, and the dawn prayer would have between five and 10 people. Nowadays, he says, the mosque is full nine rows deep for prayer.

Not everyone has cheered the changes. “We are growing here. But I know the area is very racist. People carry a lot of hatred toward this community of ours,” Khattab told me. He said the town’s Muslims were shocked but not entirely surprised by what happened to Wadee. After the war in Gaza began, Khattab noticed a heightened anxiety in the community. “We had some incidents. We have a plaza that has restaurants and shops and groceries that are all owned by Arabs. One guy went at night, we caught him on camera breaking a couple of windows. So, we have to be careful. In public school, kids are always careful how they conduct themselves because they are representing Muslims.” (Anti-Muslim and antisemitic hate crimes had already been on the rise nationwide, and by the end of October there had already been more hate incidents this year than in all of 2022 in the Chicago area.)

“For me, I’m always on alert. The community is populated around the mosque, but they don’t know what’s going on beyond it sometimes,” he said. He remembers hearing from Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, when he was still a congressman. Ellison told him that a white supremacist terrorist organization that attacked a mosque in Minnesota with explosives was based in southern Illinois. So the community made changes. “If you go to the mosque, we usually have three of four entrances open for the prayers,” he said. “Now, we just keep one door open. We closed all the doors, and we have our own security people.”

“I know five or six people carry when they go to the morning prayer,” he said. “I had a discussion with the chief of police of the village. I said, ‘Be careful when your guys go to the mosque. Everybody is carrying a gun. If something happened, you’re more likely to get shot by friendly fire than the bad guys.’ ”

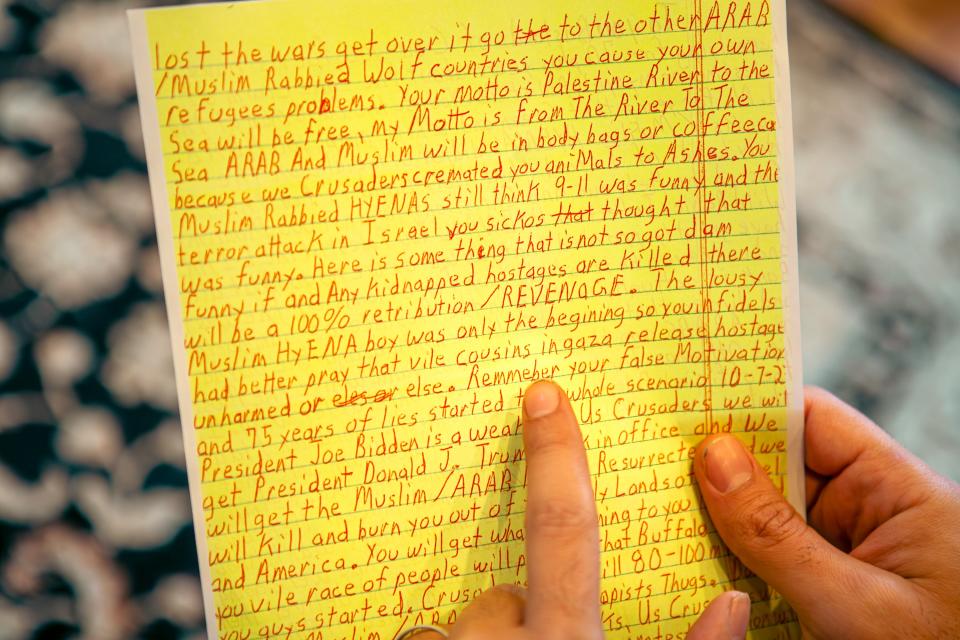

Ahmed Rehab, the executive director of the Chicago office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, said there’s no denying the link between the violence and how Americans perceive the war in Gaza in an atmosphere that he said often ignores the suffering of Palestinians. “People only see one thing. They see the hostages, they see their tears and their families, and they know it’s Muslims—not Hamas, just nasty Arabs, Muslims—that are behind it,” Rehab said. “People will take matters in their own hands. And you see what happened to Wadee and his mother. It was a man who was radicalized by the mainstream media.” Rehab shared with me a handwritten death threat he received at his office a few days ago. It was addressed to him, called him “a dead man,” and threatened violence. “Do not worry about watching your backs. Us crusaders will behead you Muslim rats,” the letter read. It added: “The lousy Muslim hyena boy was only the beginning.”

Since the child’s killing, Rehab has been meeting with political figures behind the scenes and urging them to take this threat more seriously. “I said to Sen. Durbin”—Dick Durbin, the longtime senator from Illinois—“he wasn’t radicalized by some right-wing blog. He wasn’t a member of some underground white supremacist group. He wasn’t a member of some illegal militia. He was a normal grandfather-type guy, a landlord who liked the kid, who the kid liked and called him grandfather. He played in his backyard, he built him a treehouse, he allowed him to use the pool, he brought him toys, and this man was radicalized,” Rehab said.

Rehab had helped shore up support for Wadee’s parents directly after the killing, both financial and otherwise, including hiring a therapist for his mother. He was afraid of how quickly the story could change. “I’m old enough to remember Chapel Hill. It quickly became a parking dispute story,” Rehab said referring to the three Muslim students who were shot to death by a neighbor in North Carolina in 2015. “On this one, we got ahead of it early with a big press conference with national and global news. The president responded and the governor came to the funeral. The president called the family and sent a letter. We helped the whole world move in the right direction about it, condemning it, calling it what it is,” Rehab said.

During my visit, I stopped by to look at the house where Wadee had lived. It looked ghastly, with a small memorial on the street with sports balls and teddy bears laid out and a small Palestinian scarf wrapped around a flagpole flying an American flag. Czuba’s truck is still parked next to the house. The back of it is covered in Christian bumper stickers with calls to support children. One is a quote from Pope John Paul II: “A nation that hurts its own children is a nation without hope.” Another sticker says “Children, our most precious natural resource.”

As I walked around, a neighbor came outside to confront me. She threw her hands up in the air and shouted, “Can I help you?” I asked if I could talk to her, and she yelled at me to get away. As she walked back up her driveway, she told me that news trucks have been parked outside of her home nonstop, and that she’s had enough. “The whole country needs to calm down,” she said.

Odai arrived early the morning of his son’s funeral to conduct the ritual washing of the body himself. “I was the one who washed him when he was born, and I was the one who washed him when he died,” he said.

For many people who attended the funeral in Little Palestine—“it was the largest the town had ever seen,” Khattab said—Odai noticed that it seemed to bring closure. But for him, it was just beginning. The support he’s had so far has both heartened and frustrated him—the latter happening more when it comes from people outside of his community: “Big names reached out. My brain cannot grasp that. Joe Biden called me and was crying. He said he had a son who died. He said he sympathized with me and felt for me.” But he didn’t see the losses as the same, and said he can “smell hypocrisy” when it came to American policies in Gaza and elsewhere. He can barely leave the house for work, but he plans to be there in court as Czuba’s trial unfolds. He hopes others will pack the room.

“I don’t feel anything,” Odai said. “If you ask me as a father of this child, life now only has two tones, black and white. If I eat any kind of food, there’s only one taste. If I drink anything, same thing. I don’t feel anything anymore. Will things change for me? I don’t know. Everything is in God’s control.”

Hanan, on the other hand, smiled as she talked about all of the support and love she received after what happened. “I think this hate happened to show me after it the whole love from everyone, the sheriffs, the FBI, the attorneys, they all came to support me. Alhamdulillah. They are taking good care of me. And I will continue to wish for all of us to have peace and happy days. Alhamdulilah.” When I went to take her photograph for this article, she carefully turned her head to avoid showing most of her wounds. Again and again, she told me that she wanted people to see she is OK.