5 Ways to Help Your Child Get the Most Out of International Travel

Luci Gutierrez

Maru Schwartz's son William had visited his great-grandmother's Mexican village so many times by age 7 that he barely acknowledged the differences between La Candelaria Tlapala and his native New York. He'd gotten used to eating tortillas at every meal; he loved seeing cows amble down the unpaved main street; he managed to communicate with his bisabuela despite speaking little Spanish. And then he noticed one big difference. After running into local friends on the street and seeing their toes poke through their worn-down footwear, he asked, "Mami, what's wrong with their shoes?" For Schwartz, the question marked a new level of awareness in William—one that she was ready for. "I was expecting it for years, because I had the same question when I was little," Schwartz says. She took the opportunity to explain economic differences between home and Mexico and remind William that it should change nothing between him and his friends.

For many moms like Schwartz, summer break is the perfect opportunity to take the kids to visit family in Latin America and soak up the local color. These trips can be rewarding: "It's the number-one thing you can do to raise your child to be bilingual and bicultural," says Ana Flores, cofounder of the popular parenting site SpanglishBaby.com. But the trips can also be stressful. We asked parents and experts to share their best tips to deal with five common scenarios so you can prepare your kids for travel and handle blips on the road.

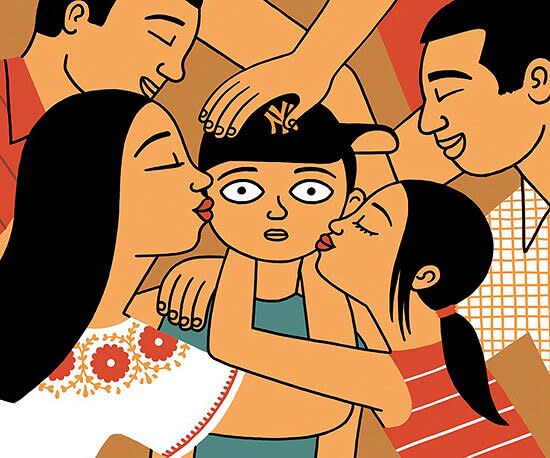

1. "Who are all these people?"

One of the main reasons parents travel to their home country is to give kids an opportunity to bond with extended family. Last year, ahead of a trip to her native Colombia, Angela Adrar thought she'd readied her 3-year-old son, Kingston, by showing him family Facebook pages while still at home in Washington, D.C. But when some 40 relatives all eagerly hugged the naturally shy Kingston at his third birthday party in Bogot?, he felt dazed. He couldn't keep up with the rapid-fire Spanish or overwhelming affection. He withdrew to Adrar's side—and stayed there for an hour. After letting her son have time to himself, Adrar asked a pair of cousins to help make Kingston feel more at home by speaking to him in English and playing with him in a small group. By the end of the night, the boy was dancing in the middle of the room, surrounded by family.

Giving Kingston allies and time to build up to conversation and play is a great move, says New York City psychologist Carmen Inoa Vazquez, author of Parenting With Pride, Latino Style. "It can be a little overwhelming for a child to meet so many relatives," she says. Well-intentioned aunts and uncles often "want the child to hug them as if the child has been with them all their lives, and it doesn't work that way." Talk to relatives beforehand, Vazquez suggests. "You can say, 'My child gets anxious when there are lots of people around her.' With some explanation, they'll understand."

2. "Sorry, no hablo español."

On visits to San Salvador during daughter Camila's preschool years, Flores had a simple, effective tactic for strengthening her daughter's Spanish: Put her in day care. Practicing Spanish with native speakers her own age helped Camila build on Flores's efforts to make her bilingual and biliterate; these include supplying Camila with Spanish-language books, movies, and apps and having her attend a dual-language immersion school at home in Los Angeles. Speaking Spanish also strengthened the bond between Camila and Abuela, paving the way for more enjoyable future trips. "Now, as soon as she gets off the plane in El Salvador, there is no language barrier between them," says Flores, noting that many preschools and day cares abroad are receptive to enrolling vacationing kids for as little as a week. Depending where your family is from—our summer is South America's winter—your visit may even land during the school year. Vet schools through relatives, and be sure to call ahead to arrange.

Though reinforcing language is key, Vazquez says, it's important not to feel anxious if your kid resists speaking Spanish. "Your child is in another country and culture, taken away from what she's used to," she says. "Keep teaching, but let her be." After all, some things transcend language. Schwartz's abuela made William feel special by eating breakfasts together and taking him along to feed chickens and run errands, describing their activities in Spanish to help him learn. Village kids, Schwartz recalls, engaged William with a simple question: "¿Quieres jugar?"

3. "Mami, why is that girl begging?"

In Latin America, poverty can be very visible and may even affect loved ones. Don't avoid addressing it, says Vazquez. It's a chance to teach values such as tolerance, gratitude, and compassion, she adds. If your child is saddened by the sight of poor kids, "have a dialogue about the importance of being tolerant of differences," says Vazquez. "Tell him that not every child is lucky to have the things you do and that no child should be hungry or go without clothing. It's our responsibility to help them." Rather than handing out money in the street, ask the child's parents, if they're present, what their family needs, Vazquez advises, or donate to child-education organizations.

Schwartz turned William's concern for his friends' footwear into action. "I told him that some kids' parents can't afford shoes, so they have to wear them out," Schwartz recalls. "So what if your friend is not playing with sneakers on? You're still friends." Then she suggested he donate some of his clothes at the end of the trip. "That made him really happy." Flores took the idea of helping one step further. Two years ago, when Camila was 5, they sponsored a Salvadoran girl named Brenda through Save the Children. It's a way of making kids aware of need, and it prepares them for seeing poverty up close, as Camila did when they visited Brenda in her mountain village. "Camila lives in L.A. and has First World problems," Flores says. "I needed her to see that life is different in other places. She knew that Brenda didn't have the commodities she did." Seeing the village's four-room schoolhouse, the water pump that served as the residents' sole source of water, and the family's dirt-floor home they'd built themselves opened Camila's eyes. "It's already shaping how she sees things," says Flores. "She now knows that when I tell her to eat her food because there are poor people in the world, I mean people like Brenda."

4. "I'm not eating that!"

The scene played out time and again in Tlapala, says Schwartz. Relatives would "go all out making mole and pozole from scratch" but have to set out plain cooked chicken for William. "He didn't like the texture or the spice," Schwartz says, adding that she let her son decide what new foods he wanted to try. "It was more important for me not to force the issue." Getting kids to try new foods abroad can be as big a roadblock as it is at home, notes Vazquez—especially if they're not used to, say, Mexico's chile peppers or Ecuador's chunky soups. Parents can preview some typical dishes by cooking them before trips abroad or by taking kids to Latino restaurants at home. In the case of a very young or picky eater, Vasquez suggests bringing along portable, familiar foods, such as cereal. During the trip, encourage your child to explore foods by eating them yourself and pointing out other kids who are digging in to their meals. But don't pressure him, Vazquez says. "As the saying goes: A la fuerza ni el zapato entra. They might surprise you and try it after you walk away."

5. "Do I have to kiss everybody's cheeks every time I see them?!"

It can sometimes be hard for kids to grasp cultural traditions—and there might not be much you can do about it. As engaged with Latino culture as Camila is—she prefers a plate of platanos fritos con crema y frijoles over pizza—there's one tradition she does her best to avoid: cheek kisses as a greeting. "She just doesn't get it," Flores laughs. "I say, Camila, that's what we do! For my husband and me, it's hard, because we're, like, 'Eso es mala educación.' And Abuelita is, like, 'No le estas enseñando modales.' "

Though besitos can never truly be legislated, there's a lot you can do to encourage kids to pick up other traditions. When Kingston was confused by the sight of Medellín residents riding horses through city streets, Adrar explained the tradition of cabalgata, parades in which paso fino horses walk with a distinctive gait. She recruited a ranch-hand in the outskirts of Medellín to teach Kingston to ride. "He loved it," Adrar says. "I brought my kids to Colombia because I wanted them to truly experience their culture." And that's exactly what happened.