5 Insights from Training with a Continuous Glucose Monitor

Last year, while reporting this article on the emerging trend of endurance athletes using continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), I tried it myself for two months. The initial article focused on the science (sparse though it is) behind claims that knowing what your blood sugar is doing at any given moment can help you fuel more effectively and perform better. But I figured it would be fun to share some of my actual CGM data--so what follows are five representative samples that illustrate some of my experiences.

To help me interpret this data, I called Kevin Sprouse, a sports medicine doctor in Knoxville who also serves as head of medicine for the EF Education-Nippo pro cycling team. Sprouse uses CGMs with his Tour de France cyclists (though not during competition), as well as with recreational athletes in cycling and other sports.

To start, I emailed him some workout data--which, it turns out, is totally the wrong approach. "It's really important to look at the 24-hour period around the workout," he explained when we talked. "Looking at just the workout is a mistake. It's myopic." Low blood sugar during a workout might be the result of a bad dinner the night before. High blood sugar might simply indicate that you didn't get enough sleep. Without those contextual clues, the workout data alone won't tell you much.

With that caveat, here's some data, with glucose measurements on the left axis and running speed (measured with a Wahoo GPS watch) on the right axis:

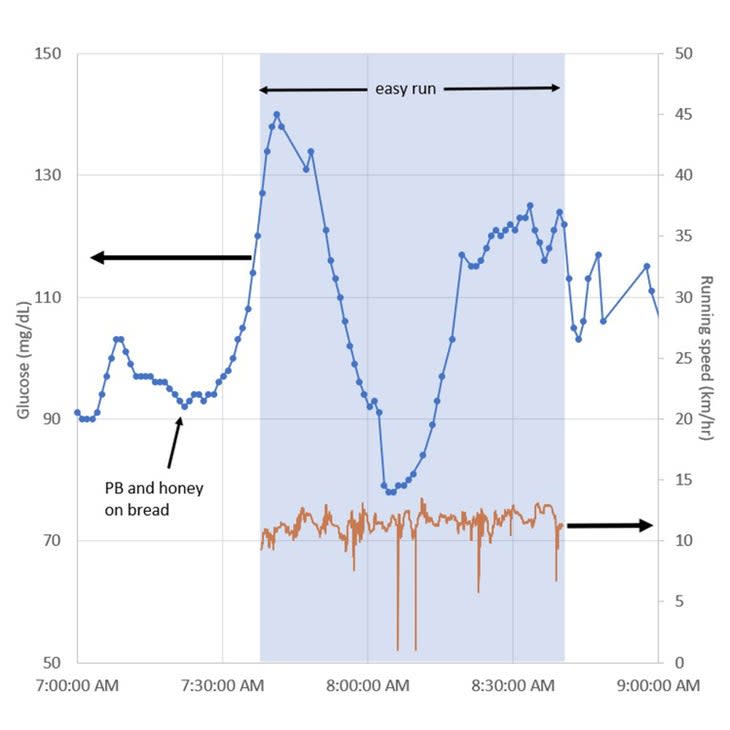

March 28: Easy 7.5-Mile Run

This was an easy run with a friend at about 8:00/mile pace, and the data is pretty typical of what I saw in the first month or so of wearing a CGM. But there's a problem with the data. You can see the minute-by-minute updates when I'm eating my pre-run banana. But once the run starts, I'm only getting readings every 15 minutes. That's because I left my phone behind, and the CGM itself only records readings every 15 minutes, which are then uploaded to your phone next time you connect. So this pattern may be missing some important fluctuations during the run.

Supersapiens has since launched a dedicated wrist reader for people like me who hate running with their phones. But once I realized the problem, I borrowed a pink narwhal fanny pack from my daughter and started taking my phone along.

April 8: Interval Workout

With my phone in my pocket, I now see a lot more action in the data. This workout consisted of a 15-minute warm-up; four sets of (roughly) 1:00 hard, 1:00 easy, 3:00 hard, 1:30 easy; 15-minute cool-down. During the hard portion of the workout, you can see my glucose levels climbing like a staircase.

This was interesting to me, because the simplistic way of thinking about a CGM is that it's a fuel gauge, telling you how much juice you've got left in the tank. That's clearly not the case in this context: the harder I go, the higher my glucose climbs, producing a nice staircase pattern. As my muscles start burning through fuel more rapidly, extra energy from reserve tanks like the carbohydrate stored in my liver is being released into the bloodstream to keep me sprinting.

Then, when I finish my intervals and start jogging slowly home, my blood sugar remains sky-high (anything above 140 is considered unusually high) because I've ramped up my fuel system but am no longer working as hard.

Those readings of 170 at the end of my workout are certainly high, but likely nothing to be worried about, Sprouse says. One good sign: as soon as the workout ends, they drop very rapidly into a more normal range. That likely indicates that my body didn't need to produce a spike of insulin to bring my blood sugar back down. If I'd taken a gel or other fuel during that workout (which I didn't), Sprouse would have counseled me not to bother, as my glucose levels were already high enough.

May 18: Zoom Presentation

On this particular day, I gave an online presentation to a non-profit group. It was just 15 minutes long, for a small and friendly audience. But hey, I still get nervous. It was fascinating to see how life events, and mental state more generally, affected my blood sugar levels. In the context of exercise, think about the difference between an easy run, a hard workout, and an important race. Your pace is different, but so are your stress levels. In the interval workout above, how much of that staircase effect was feedback (my muscles need more glucose) and how much was feedforward (my brain is on high alert, mobilizing bodily resources in anticipation of demands)?

It's also interesting to see the crash afterwards. I often feel like a squeezed-out sponge after giving a talk; here's the physiological correlate. Levels below 70 are considered unusually low. How did I respond? Probably by eating something sweet, hence the subsequent spike at around 3 P.M. (For the first month or so of wearing a CGM, I dutifully entered every meal and snack into the Supersapiens app, but by this point the novelty had worn off and I was mostly only recording pre-workout meals.)

May 20: 42-Mile Bike Ride

I'm not much of a cyclist, but one of the situations I wanted to test with the CGM was an extended workout where I might conceivably bonk. Would the feeling of hitting the wall actually correspond with an unusually low blood sugar reading? It doesn't always, Sprouse told me: "We've all thought we were bonking and really we just weren't very fit."

I arranged to go for a four-hour ride with a friend, mostly at a relaxed pace. The exception was the first 20 minutes or so, when I rode hard because I was late for our meeting, and the last half hour, when I rode hard just for the heck of it. In this graph, the right-hand axis is my heart rate instead of speed.

The overall picture is roughly what you'd expect, Sprouse says. Glucose levels are relatively stable during the main part of the ride, but gradually start to edge downwards after about 1.5 to 2 hours. I deliberately didn't fuel at all during this part of the ride, to see how low I'd go. When we finally stopped for a short break after around three hours of riding, my glucose levels dipped all the way down below 70. Then I hit them with a gel and a Larabar, totaling 50 grams of carbs, and you can see my blood sugar instantly respond with a huge spike.

About half an hour after the fuel surge, I split off from my friend and started hammering home. One unanswered question is whether my blood sugar was going to plunge following the spike no matter what, or whether the plunge was precipitated in part by the fact that my muscles suddenly started burning fuel more quickly. My suspicion is that the main decrease is a response to the sugar-fueled spike--but then, with about ten minutes left in the ride, I started heading uphill for the final stretch. At that point, you can see my heart rate spike, and the blood sugar levels briefly increase again, just as they did during the hardest parts of my interval workout.

Sprouse's take, phrased more politely, was that I'd fueled like an idiot for this ride: nothing at all for three hours, and then mainlining a big bolus of sugar. (He understood, when I explained, that I was trying to produce extreme values with the CGM.) If I actually wanted to optimize performance, he said, the graph suggested that I wouldn't have needed any fuel for a ride like this lasting up to perhaps two hours. For the longer ride, I would benefit from smaller, more frequent doses of fuel--perhaps half a banana here, a few sips of sports drink there, and so on.

May 23: 7-Mile Easy Run

This was another Sunday morning easy run, very similar to the one from March 28 except that I brought my phone with me to get proper data. But this time, my blood sugar levels are swinging around wildly. As with the bike ride, this was partly by design. Normally I eat little or nothing before heading out for a morning run. This time, I had a peanut-butter-and-honey sandwich--because I knew it would mess with my blood sugar.

For as long as I can remember, I've experienced something called rebound hypoglycemia. If I eat something, particularly if it's carb-heavy, 30 to 60 minutes before a morning run, then 15 minutes into the run I'll start feeling light-headed. It'll last five to ten minutes, then disappear. What's happening, I've gathered, is that my breakfast or snack triggers a delayed insulin response that kicks in roughly when I'm starting my run. Both insulin and exercise are then trying to lower my blood sugar, and it overshoots before getting balanced out.

I wanted to see this in action, hence the sandwich. You can see that my levels are rising sharply before I even start running. Then after about ten minutes of running, they start dropping. On this particular run, I didn't get the full light-headedness, but did feel pretty sluggish for a while. Then the levels eventually stabilize at a suitably elevated level for the rest of the run.

Sprouse's advice for this situation caught me off-guard: he suggested throwing in a brief sprint. Just as during my interval workout (or even my online talk), ramping up the effort and adrenaline will jolt your blood sugar upward. Interestingly, he said that during the Tour de France, he tells riders not to have a final pre-race meal in the couple of hours before stages that start with an uphill, since they may need to be ready to go hard right from the gun. For initially flat stages, which usually start by noodling around gently, they can go ahead with the extra meal two to three hours before--but then keep gels ready in case they need a boost early in the stage.

So what's the overall takeaway from all this? To be honest, I didn't get a chance to put the device through its proper paces. This was mid-pandemic, when races were canceled and my four- and six-year-olds were both learning from home. I had trouble slipping away to train for more than half an hour at a time, and when I did I wasn't setting the world on fire. You can see the blood sugar spikes from when I was waking up in the middle of the night and worrying about the state of the world.

Still, there are some glimmers of the CGM's potential: for dialing in the fueling on long rides, for figuring out how to avoid rebound hypoglycemia, and for seeing the way my body reacts to stress. That said, as Sprouse pointed out, you really need to zoom out from individual workouts to see the 24-hour context, and the daily or weekly patterns. That's a lot of data to sift through, and Supersapiens' big challenge (which they've been chipping away at since my trial run ended in June) is to translate it into digestible and actionable advice--even for those of us who don't have someone like Sprouse on speed dial.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.