The 5 Campiest Musicals Ever Made

The American musical theatre tradition is a veritable camp playground. If the camp sensibility, this year's Met Gala theme, hinges on an appreciation of artifice—on “seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon,” as Susan Sontag describes it in her “Notes on ‘Camp’”—then folks like Lerner, Loew, Rogers, Hart, and Hammerstein all helped to supply the sound where Art Nouveau and pulp fiction gave 20th-century camp its look. Just consider these lines in “Make Believe,” a duet from Show Boat: “And if the things we dream about don't happen to be so / That’s just an unimportant technicality … Might as well make believe I love you / For to tell the truth, I do.” For Magnolia and Gaylord, the invention—the fantasy—is the thing; a concept that captures both the charms of musical theatre itself (which, even at its most topical, maintains a disarming distance from the everyday) and camp’s “glorification of ‘character,’” per Sontag. To be camp is to put it on . . . to do a whole song and dance, so to speak.

Gathered here are a selection of movie musicals—some original, some adapted from the stage—that brought camp’s muchness to the Hollywood soundstage. Far more than the sum of their strangely specific parts (a rock opera . . . about Jesus Christ?), these films are all too deliciously fun—and weird!—not to sit down and watch this very moment.

The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967)

MSDYOGI EC004

Photo: Everett CollectionJacques Demy—husband of the late, great Agnès Varda—followed up the smashing international success of his 1964 musical feature The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, starring Catherine Deneuve and Nino Castelnuovo, with The Young Girls of Rochefort, in which Deneuve appeared with her older sister, Françoise Dorléac. Veering sharply away from the former film’s wistful romanticism (buttressed by Michel Legrand’s jazz-inflected score), The Young Girls of Rochefort is a high-energy, intensely-over-saturated rom-com-slash-murder-mystery. That George Chakiris (who played Bernardo in the 1961 film adaptation of West Side Story) and Gene Kelly are both in the cast is no coincidence: Demy conceived of The Young Girls as a tribute to the Hollywood musical. He gets a lot right—sprawling dance sequences flood the sleepy, sun-bleached port of Rochefort with good cheer—but where his project goes slightly off the rails is also kind of what makes it great. Alluring as they are, neither Deneuve nor Dorléac can sing or dance very well; a fact that would rankle in another movie, but here, for whatever reason, is adorable. Also, there’s an ax murderer!

In the New York Times, Renata Adler described The Young Girls of Rochefort as a film in which “a conventional, gay form is structured over what would be, in its terms, a catastrophe.” The Camp crops up in its tangle of contradictions; the gap between what The Young Girls makes itself out to be, and the traits that it actually presents. “There are many strange songs, and dances and contretemps,” Adler continues. “There is a lot of witty, high elegant and absurdist dialogue and some terrible puns … The music, by Michel Legrand, is sometimes funny, sometimes undistinguished, and sometimes just lovely”—elements that, taken together, add up to a “fine, eccentric, pastel and dreamlike irony.” In other words: high camp!

On A Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970)

M8DONAC EC003

Photo: Everett CollectionIn On A Clear Day You Can See Forever, a clairvoyant named Daisy Gamble (Barbra Streisand, in a role originated on Broadway by Barbara Harris) calls on a psychiatrist (Yves Montad) to help her quit smoking—and learns while hypnotized that in a previous life, she’d been one Lady Melinda Winifred Waine Tentrees, a Regency-era seductress. All manner of frothy, dramatic comedy ensues when, over the course of her sessions, Daisy’s doctor begins to fall in love not with Daisy, exactly, but with Lady Melinda.

What makes this movie camp is not only its scheherazadian plot line and intensely overqualified cast and crew (Vincente Minnelli—of Meet Me in St. Louis and Father of the Bride fame—directed; and filling out two of the film’s supporting roles are Bob Newhart and Jack Nicholson, of all people), but also its completely over-the-top costumery, the best of which was conjured by none other than Cecil Beaton. Among the highlights is a long-sleeved empire-style gown in optic white, edged with hundreds of faux pearls and rhinestones and finished with an enormous white turban absolutely heaving with bijoux. (And indeed, Streisand’s vocals on the sumptuous and seductive “Love with All the Trimmings” suit the look.) “I tried to stress the lushness of the fabrics, the intricate designs and motifs, in short, the physical if not spiritual splendor of the period we were dealing with,” Beaton explained in an interview. “On a less gifted actress and model, on almost any American actress I can think of, this would have been wasted and somewhat ludicrous.” Ludicrous, it is not—but camp? Quite!

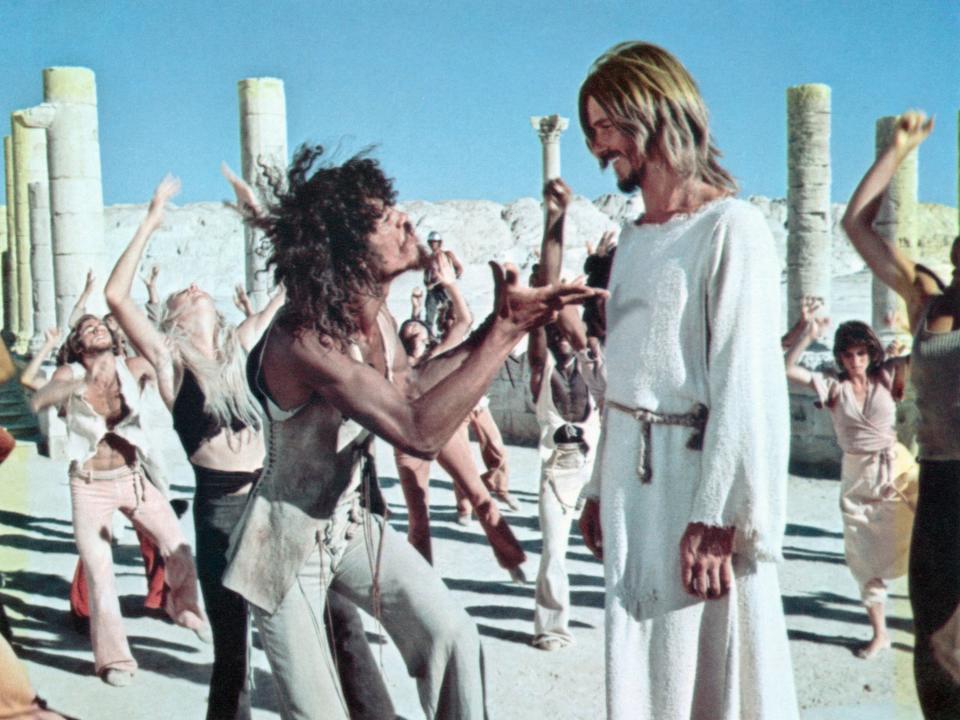

Jesus Christ Superstar (1973)

M8DJECH EC003

Photo: Everett CollectionDon’t let its recent adaptation as a common concert special fool you: Jesus Christ Superstar lives right on the razor’s edge of good taste. With music by Andrew Lloyd Webber (the man behind Evita, The Phantom of the Opera, and—lest anyone forget it—the feline phantasmagoria that is Cats) and lyrics by Tim Rice, Jesus Christ Superstar spins New Testament narratives like the cleansing of the Temple and the Last Supper into the stuff of high drama, with Judas Iscariot playing the villainous outcast, and Mary Magdalene, the tortured love interest.

As a modern retelling of an ancient story, Jesus Christ Superstar is extremely on-the-nose: Guitar-heavy tracks with names like “What's the Buzz?/Strange Thing Mystifying,” “Gethsemane,” and “King Herod’s Song” make up its lengthy score. As a Hollywood film, however—helmed by the esteemed Norman Jewison (Fiddler on the Roof)—Jesus Christ Superstar is camp heaven. Take, for instance, the “Simon Zealotes” tableau, in which Simon and his merry band of acolytes emerge from the desert like apparitions, professing their devotion to Jesus Christ (played by an indubitably hunky Ted Neeley) through choreography that calls to mind a cocaine-fueled aerobics class. Their determinedly anachronistic costumes (are some of the zealots wearing Lycra?) add to the unreality; the sense that Jesus Christ Superstar is as much an aesthetic (and commercial) exercise as any of Webber’s other creations. “Camp,” Sontag asserted, “involves a new, more complex relation to ‘the serious.’ One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.” Sure, there’s an important story in Jesus Christ Superstar about faith and morality and influence, but there are also large, sculptural hats; tiny, tinted sunglasses; and angels with white afros—camp fare if I’ve ever seen it.

The Little Shop of Horrors (1986)

A137FN

Photo: AlamyWhile the camp-horror nexus has produced films as various as Young Frankenstein (1974), Death Becomes Her (1992) and the Paris Hilton-fronted slasher flick House of Wax (2005), the camp-horror-musical nexus may well begin and end with The Little Shop of Horrors. Adapted from an Off-Broadway musical—itself inspired by a 1960 B-movie of the same name—The Little Shop of Horrors follows Seymour Krelborn (Rick Moranis), his love interest, Audrey (Ellen Greene), and Seymour’s man-eating alien-plant, Audrey II. Alan Menken’s infectious music, which flips between mid-century doo-wop and bluesy rock and roll, gives a sometimes silly, sometimes authenitcally frightening allegory for the dangers of consumerism a serious sense of fun.

If Little Shop is a touch too self-aware to be pure camp—“there’s the sense,” Robert Ebert observes in his review, “that ‘Little Shop’ is amused by just about whatever comes into its mind”—the amusing affectations of its particular cast of characters (the bumbling, bespectacled florist’s assistant; the doe-eyed, dippy blonde; Steve Martin’s brilliant turn as a sadistic dentist) certainly put them in the neighborhood. “What Camp taste responds to is ‘instant character’,” Sontag writes. “Character is understood as a state of continual incandescence—a person being one, very intense thing.” At the heart of Little Shop, it would seem, are a set of characters facing down another very intense thing altogether; namely, a mean green mother from outer space.

Hairspray (2007)

MCDHAIR EC069

Photo: Everett CollectionJon Waters’s contributions to the queer cinematic canon—among them, 1972’s Pink Flamingos and 1974’s Female Trouble, both starring the effervescent Divine—have been myriad; for decades, his work has narrowed in on the margins of mainstream Americans society, prioritizing the little-seen, “unwashed public,” as he put it in a 2018 interview. Although the 2007 iteration of Hairspray (an Adam Shankman-directed remake of Waters’s 1988 film, and its subsequent Broadway adaptation) is set a ways apart from the bulk of his oeuvre by its mainstream appeal, Hairspray still hangs on to the cheeky kitsch that’s long been Waters’s calling card.

Proudly flying the flags of both body-positivity and racial equality (the action unfolds in early-1960s Baltimore), the brassy musical isn’t camp in its message so much as in its unabashedly outré optics. In keeping with tradition, there’s a drag element: As Edna Turnblad (mother of the spunky protagonist Tracy, an ebullient Nikki Blonksy), John Travolta follows in the footsteps of Divine (legally, Harris Glenn Milstead), who assumed that role in 1988, and Harvey Fierstein, who played it on the stage. While not invoked in Sontag’s “Notes” by name, drag fits neatly into her conception of camp as ultimately performative—“To perceive Camp in objects and persons,” she says, “is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role”—as of her association between camp taste and a “a relish for the exaggeration of sexual characteristics and personality mannerisms,” which is almost inevitably intensified when it’s a man doing the woman-ing.

The costumes, by Rita Ryack (Casino, How the Grinch Stole Christmas) also play their part: In one break-out number, “Welcome to the 60’s,” Edna and Tracy sashay their way through Hefty Hideaway—their favorite local retailer—dressed in matching bubble-gum pink shift dresses. To the extent that camp thrives when inhibitions are abandoned, the unadulterated optimism that’s made Hairspray a cultural touchstone is kind of as camp as it gets.