40 Years Ago, Poet Lucille Clifton Lost Her House. This Year, Her Children Bought It Back.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

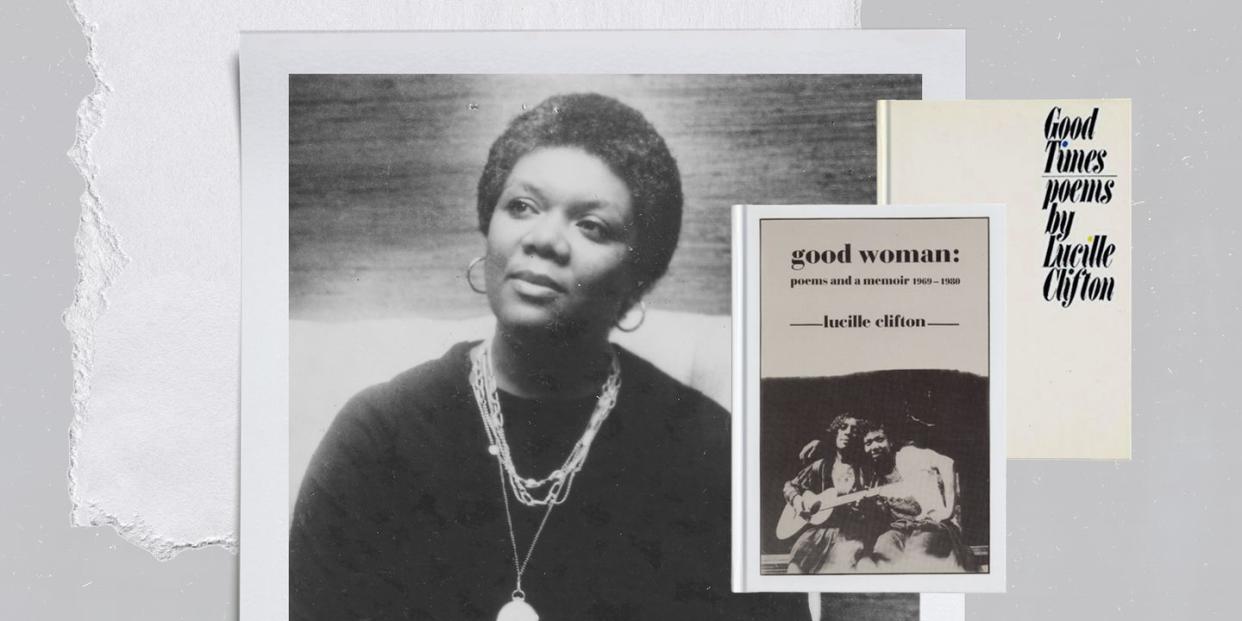

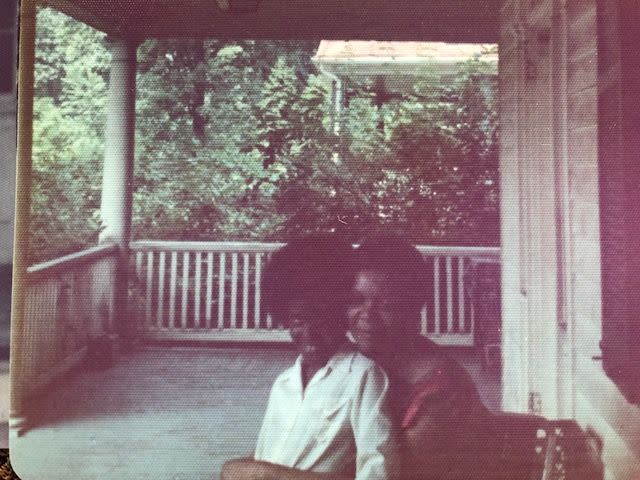

The house on Talbot Road was sacred. In the arms of its wraparound porch, poet Lucille Clifton lived and loved and danced, along with her husband, Fred Clifton, and their six children, for more than a decade. It was at the dining room table of this house that Lucille wrote some of her most celebrated collections of poetry: Good Times (1969), Good News About the Earth (1972), An Ordinary Woman (1974), and Two-Headed Woman (1980).

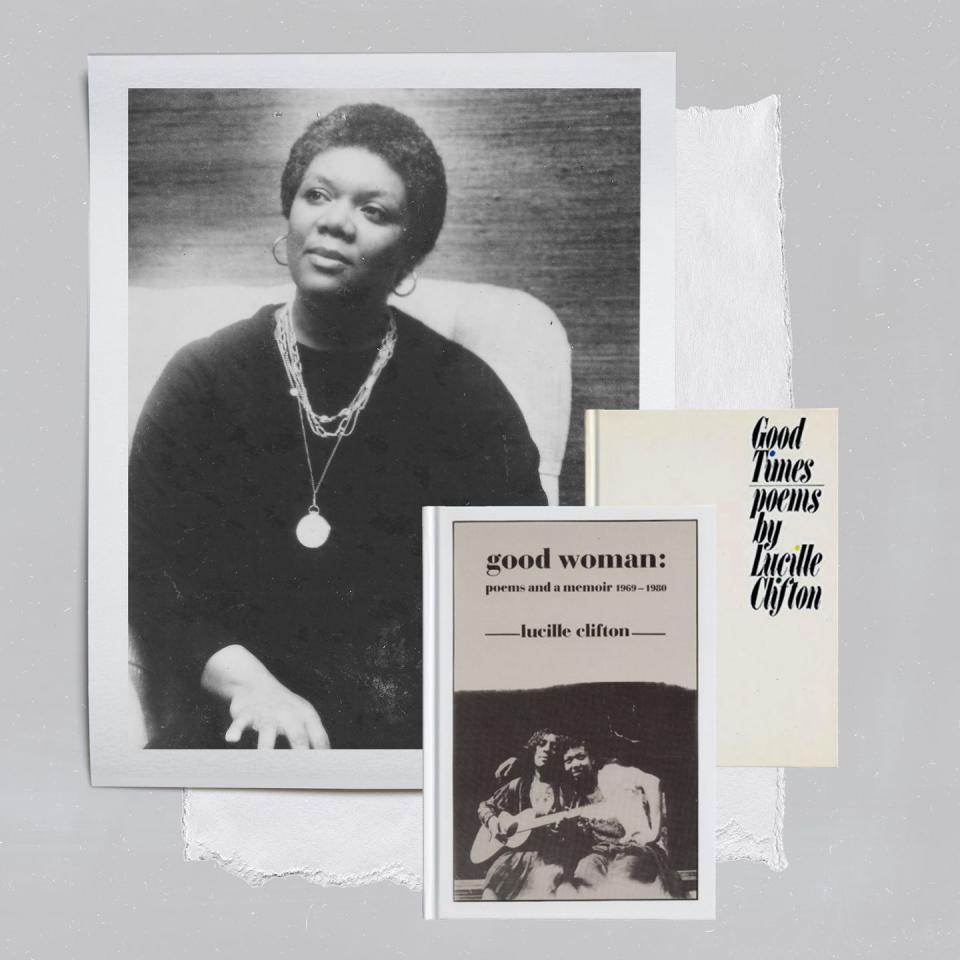

From 1968 to 1980, the Clifton family made their home on Talbot Road in Baltimore’s Windsor Hills. The rolling, forested terrain and the wood, shingles, and brick of the homes, with their signs proclaiming, “Everyone is welcome here,” made the integrated neighborhood feel like a space apart from the social unrest, the Vietnam War, and the white flight that characterized the 1970s. In this restless decade, the Clifton family found a measure of peace.

Lucille would joke that her poems were so short because she had six kids. Indeed, Lucille is a master of the epigram. Many of her best-loved poems (such as “won’t you celebrate with me,” “why some people be mad at me sometimes,” and “homage to my hair”) pack more emotional resonance into fewer lines than many novels achieve in hundreds of pages. Audre Lorde, also a mother and a poet, has argued, “Of all the art forms, poetry is the most economical […] the one which can be done between shifts, in the hospital pantry, on the subway, and on scraps of surplus paper.” In those years on Talbot Road, Lucille’s poetry fit into the mornings, in between getting her kids ready for school and picking up the younger ones from kindergarten at midday. Writing wasn’t scheduled, but stitched together from the scraps of minutes spared throughout the day.

In the 1970s, Lucille wrote poems dedicated to Black revolutionaries like Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver, and Bobby Seale, as well as poems protesting events like the Kent State shootings. She and Fred (a professor and community organizer who then served as the executive vice president of the East Baltimore Community Corporation) treated the house as an extension of their political commitments. It was a place where their people could—in the words of Lucille’s poem “after kent state”—“come into the / black / and live.” The house on Talbot Road often provided a literal sanctuary for friends of the Cliftons who had fallen on hard times. Everyone in their network knew, according to their eldest daughter, Sidney Clifton, that “if somebody was in trouble, Fred and Lu would probably be able to help.” Fred and Lu were not just a couple but an institution, the guardians of a waystation for dispossessed members of their community. Sometimes, Sidney would awake to strangers in the house, a disorienting phenomenon she now realizes her mother might not have been entirely comfortable with. However, according to Sidney, her mother also recognized her responsibility to a community that viewed Fred and Lu as “beacons of light.”

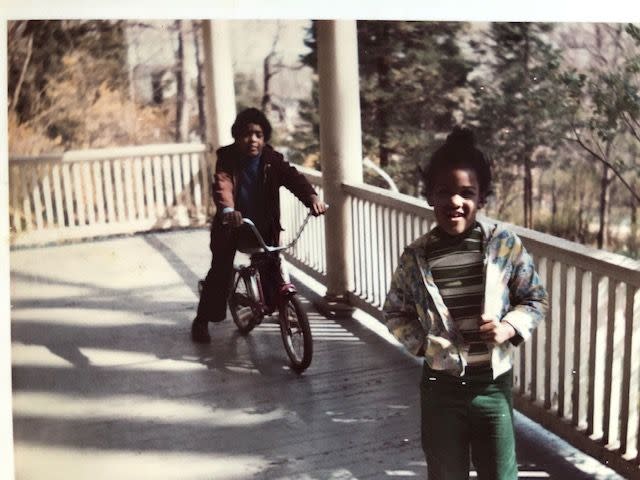

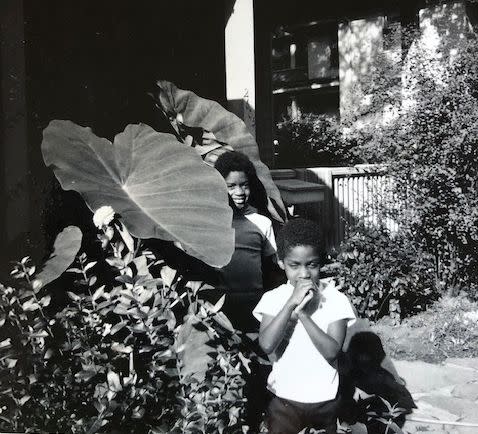

Even in the midst of a string of houseguests, Lucille carved out a space of quiet for her own writing in the dining room. This was normalized for her children, who quickly learned that you don’t bother Mommy while she’s at the typewriter. Not because they would be disciplined, but because being at the typewriter was an integral part of who their mother was. Even as children, they were aware that their mother’s writing “wasn’t a hobby.” As the eldest, Sidney learned to braid hair and make an assembly line of peanut butter sandwiches for her siblings, and even the youngest contributed to the running of the household like the tiny gears of a working clock.

While routines of work and childcare occupied the Cliftons’ days, their nights were often given over to impromptu parties. In the background, Marvin Gaye asked, “What’s was going on?” A volleyball net was thrown over the clotheslines in the backyard, Fred presided over the grill, and the older children held the babies. The adults—often community organizers and members of the service corps Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA)—ended the evenings in heated discussions of art and politics in the living room. Even as a child eavesdropping on the adults’ conversations from the other side of the wall, Sidney says, “You leave feeling a sense of possibility and purpose from those gatherings.”

Lucille nurtured that sense of possibility and purpose in her children through her writing of children’s books. She published her first hardcover children’s book, The Black B C’s, in 1970, and in 1974, she published the first of eight picture books about a young Black boy named Everett Anderson. Not only did she share these books at her children’s schools—“When you’re in fifth grade, you’re equally astounded and mortified that here’s your mom coming to your classroom,” says Sidney—but she also listened to her children’s opinions concerning what Everett Anderson should do next. As they grew older, she began to share and ask their advice on her poetry, and, according to Sidney, “It felt like an honor, even as a kid.”

When the family moved from Buffalo to Baltimore in 1968, the children were incredulous at the amount of space that their new home—with its two kitchens, three stories, and expansive yards—contained. Having attended seven different schools by the sixth grade, Sidney breathed a sigh of relief and thought, “This is really what home is supposed to feel like.”

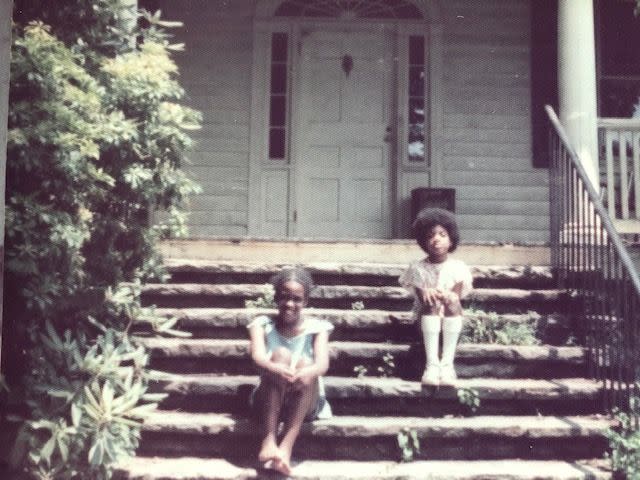

The Cliftons’ loss of their home to foreclosure in 1980 was a traumatic event. According to the children, while the Cliftons were still inside, neighbors gathered outside to place bids on the house. An auctioneer on the front steps. The neighbor who bought it told the Cliftons that they could stay but changed his mind two weeks later. In the rush to leave, not all the children entirely understood what was happening, and in the aftermath, the family was severed: Fred and the two boys went to stay with one friend, Lucille and the four girls with another. They never discussed or processed what had happened as a family. Many years later, Lucille said, “I don’t think my family ever got over the loss of our home.”

This has been the fate of many Black families in America who have lost their homes to eviction, foreclosure, and the structural violence of redlining and gentrification: to experience the loss of their spaces without adequate time to mourn. In her poem “the 1st,” Clifton wrote about an eviction she experienced with her family as a child, remembering “nothing about the emptied rooms / nothing about the emptied family.”

When Sidney bought back the house in 2019,it brought a sense of wholeness to the surviving Clifton siblings, fulfilling the prophetic lines of their mother’s 1969 poem “admonitions”: “what you pawn / I will redeem.” Sidney notes, “The reclamation of the space has been so amazingly healing.” In fact, it is almost as though the house had been waiting for them to reclaim it. “There’s so much of us still there, it’s astounding,” says Sidney. Her name, in her high schooler’s cursive, is still carved into a closet. Her younger brother Graham Clifton, who she found crying alone in the bathroom on the day they moved out, is now doing carpentry and renovations in the home he was forced to vacate 40 years prior.

“We recognize it’s a gift, so we want to be good stewards of it this time around,” says Sidney. This is why she is transforming her childhood home into the Clifton House, a space for emerging and established artists and writers. Like the house of the 1970s, the Clifton House will be porous and intergenerational, teeming with children and elders, as well as working artists. The Cliftons want visitors to the Clifton House to feel the same sense of validation they felt as children, the same feeling their mother describes in her 1972 poem “spring song”: like “the future is possible.”

You Might Also Like