Why Do So Many Horses Keep Dying at Santa Anita Racetrack?

Silver trays of fresh pastries, plates of smoked fish on tiered serving platters, and carafes of hot coffee line two sides of the conference room at the racetrack where 30 horses died in a six-month period ending in June of this year.

“All this food and no one here to eat it!”

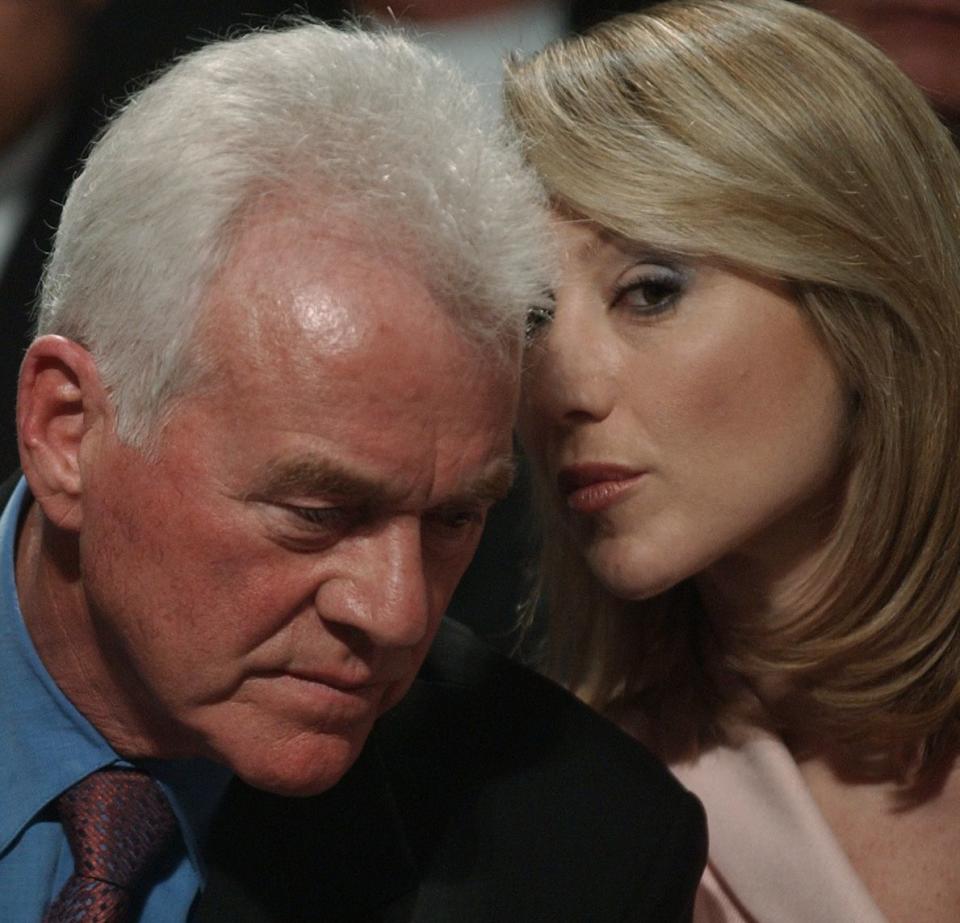

This is Belinda Stronach. The 53-year-old native of Aurora, Ontario—blond, wearing a fitted blue zip-front jumpsuit cinched with a black Gucci belt—is here today to discuss those horses and what is to be done about them. Specifically, what is to be done about the situation she finds herself in as the head of the company that owns the track where they were killed.

The deaths led the world—the Los Angeles district attorney, the California state legislature, the governor, members of Congress, and anyone who read the news—to cry tragedy and the sport of thoroughbred racing to wonder if the disaster represented its death knell.

Alone before a brunch spread fit for dozens, Belinda beckons toward the narrow end of a long oak table. “We’ve been putting a lot of focus on guest experience,” she says. “So the team here is really excited to show what they can do—but I always feel I have to eat it all myself.”

The “we” is the Stronach Group, the largest private horse track owner in the United States and currently a maelstrom of family-vs.-family lawsuits, public squabbles, and power struggles. The “here” is Santa Anita Park in Arcadia, California, 15 miles northeast of downtown L.A., a legendary racetrack that, since opening on Christmas Day 1934, has hosted countless celebrities and served as a set for myriad feature films.

Families fight. Companies evolve, sometimes painfully. Major sports are industries that endure crises the way others do. But rarely do troubles coincide with such calamitous effect as they have with this family, this company, and this sport: the tragic deaths of so many beautiful animals, the widespread public outcry, allegations of potentially unlawful mismanagement, and the $400 million lawsuit Belinda’s father, Frank Stronach, had already filed against her. And now, to make matters worse, two more horses have died, both in September.

Belinda was once a rising star in Canadian politics, winning election to Parliament as a Conservative in 2004 before defecting to the Liberal Party a year later—a shocking move even in a cutthroat world. And yet, “I think politics might have been easier, actually,” she says.

She is fighting to save not only her carefully crafted image—socialite, executive, hobnobber, politician in every way—and the business empire her family is battling over, but also an industry that generates an estimated $122 billion a year and employs 1.7 million people in the U.S. Her leadership will be tested the first weekend in November, when her troubled track hosts one of the sport’s most prestigious stakes events, the Breeders’ Cup. That is, if it’s not canceled.

She nods with studied solemnity and says, “I love animals. I like to sleep at night.”

The Horse Doctor

The dirt bakes in the late July sun. The parking lot is nearly deserted. It’s quiet. Peaceful and beautiful: the Art Deco grandstand, the palm trees, the mountains. But it was on this oval on February 23, 2019, that a prizewinning five-year-old stallion named Battle of Midway was completing a morning training session when one seemingly unremarkable stride reverberated through the pastern—a bone above the hoof that absorbs the shock of a racehorse’s 1,100 pounds with each step—on his right hind leg, shattering it instantly.

He was put down the same day.

Rick Arthur’s office (“It’s closer to a tack room,” he warns) is in a mobile home behind the rows of stables at Santa Anita. Arthur has been the equine medical director for the California Horse Racing Board (CHRB) since 2006 and a veterinarian at Santa Anita for more than four decades. Documents from his ongoing investigation into the deaths at Santa Anita are stacked high on his desk—among them the results of the necropsies for all the fatalities. “There’s nothing atypical,” Arthur says. “It’s the same issues we see over and over again. Most of them repetitive stress injuries.”

He means there’s nothing especially unusual about any one injury, or any one death. Just the number of them. However, Santa Anita was not even the deadliest track in the United States in 2018. Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby, had a far higher fatality rate, according to an investigation by the Louisville Courier-Journal. (The track itself doesn’t share information about race-related fatalities with the public; only 25 of the 96 thoroughbred tracks in the U.S. do.)

By the time Battle of Midway suffered his catastrophic injury, 17 horses had already been euthanized at Santa Anita during its Winter/Spring Meet, which began December 26. The mounting death toll received some coverage, but this incident seemed different. Battle of Midway was a famous horse—he had won the 2017 Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile and finished third in the Kentucky Derby the same year. What’s more, the fatal injury occurred during a training session. It wasn’t a case of a jockey pushing too hard in pursuit of a purse. This suggested problems with training practices, or the track itself. Or both.

Last winter was not just unusually cold and wet in California—a series of weather phenomena called atmospheric rivers caused torrential rain and flooding, particularly in February. So although a track might be muddy on its top layer, as large volumes of water drain through the dirt and sand below it, the track’s foundation can compress and harden like cement.

“Clearly, the surface had a lot to do with the spike in injuries,” Arthur says. “Whether it was the rain or the way it was maintained or running when we probably shouldn’t have run—those things are being analyzed.”

Since 1941 a bronze statue of Seabiscuit has greeted visitors to Santa Anita. The horse recovered from a serious leg injury at the track in 1939, then won the final race of his career there the following year in record time. Many wonder whether Seabiscuit’s story would have ended differently today, especially if he ran on the surface early in the year.

Arthur has described the tragedy at Santa Anita as a perfect storm—a confluence of awful weather, unfit horses running, pressure to fill races, and a lack of caution by multiple parties. “One of my major frustrations and problems with horse racing is everybody wants one issue,” he says. “They seize on medication. Trainers want to tell you it’s on the racetrack, right? Because that absolves them of responsibility. The track tells you it’s on the trainers, right? Because that absolves them of responsibility. The fact of the matter is it’s everybody’s responsibility: the regulators, the trainers, the track operators.”

The issue is rooted in economics. “You have to put horses first,” says Arthur. “Part of the problem in horse racing is, we have commoditized horses, and when you commoditize horses, you treat them like livestock because they have a value. As one trainer told me, ‘I don’t like to leave any money on the table.’ But the other side of that is not good, because that means you want to get the last pound of flesh out of that particular animal.”

The Irate Patriarch

“Oh, hello. This is Frank Stronach.” The voice on the other end of the line sounds every bit like the 86 years behind it. He immediately shares his personal cell phone number.

Stronach’s call is unexpected. Less than an hour ago his office laid out the conditions under which he would consider giving a comment: Questions were to be shared ahead of time, in writing, and his responses would be in writing as well.

As our conversation progresses, it becomes apparent why his team might want to control his interactions and review his responses. Once Frank starts rolling, he’s hard to stop. His meandering, hourlong monologue covers, among other topics, his passion for urban farming in Baltimore, his admiration for livestock psychologist Temple Grandin, and the looming threat to capitalism. (“We’ve got less capitalists,” he says. “In nature, when you’ve got a species which does not reproduce itself, another species will take over.”)

Born and raised in Austria, he’s a self-made billionaire, an immigrant success story. He arrived in Canada with $200 in 1954, founded the auto parts company Magna International three years later, and built it into a giant with revenue of $29 billion in 2011, the year he stepped down as chairman.

In 2013 he ran a maverick campaign for prime minister in his native Austria, touting his business acumen, flirting with right-wing populism, and making a few outlandish claims (that Austria was in danger of being invaded by China, for example). He won a seat in Parliament but didn’t come close to becoming head of state; he then resigned after just five months. And though he showered Belinda with privilege, he also sent her to public school near the family compound in Aurora, Ontario. After a year of college she joined the family business and married a Magna executive, Donald Walker, with whom she had two children.

Belinda had preceded Frank into politics, leaving Magna to run for a seat in the Canadian parliament, where she served from 2004 to 2008, before returning to the family business. Prior to assuming his seat in the Austrian parliament, Frank gave up his post as super-trustee of the Stronach family trust (the holdings of which include the Stronach Group), anointing Belinda in his stead and naming her children trustees. At the same time, Frank had papers drawn up that, he claims, would allow for his reappointment at a time of his choosing.

Belinda disagrees and has refused to relinquish her post. And as she tried to curtail Frank’s extremely costly and eccentric passion projects, tensions mounted. Family members chose sides. Belinda’s mother Elfriede sided with Frank, and so, reportedly, did Belinda’s only sibling, younger brother Andrew, a reclusive devotee of sustainable farming who separately sued Belinda and her top lieutenant at the Stronach Group. Later Andrew’s then 18-year-old daughter, Selena, sued Belinda as well.

Frank’s lawsuit names not just Belinda but her two children: Frank Walker, aka Frank Jr., an EDM DJ; and Nicole Walker, an equestrian. It accuses Belinda and then–Stronach Group CEO Alon Ossip of liquidating assets over his objections and starving Adena Farms, his grass-fed organic cattle ranch, of resources while spending more than $50 million in corporate funds to subsidize Belinda’s jetsetting lifestyle. Ironically, according to reports, the act that drove Frank to sue was Belinda’s decision to sell his beloved private jet. The Stronach Group, Belinda, Nicole, Frank Jr., and Ossip all deny the allegations. The lawsuit is pending.

“I would hold back a few interesting things, because it’s very sensitive,” Frank Stronach says on the phone. “I have a daughter. I don’t want to destroy her, but she needs a little dressing down… She stepped out of line.”

Once the string of fatalities at Santa Anita made the news, in early 2019, Frank began proposing racing reforms. In April he authored a “Horse Racing Bill of Rights” that would, among other things, use a percentage of the money bet on races to pay for horse care in retirement and to grant racehorses eight weeks of vacation per year.

And in a “Message to Stakeholders of the California Horseracing Industry” dated July 2, Frank blamed the racehorse fatalities at Santa Anita directly on two issues: overmedication and the lack of a proper foundation for the track. Frank claims that he was urging officials at the Stronach Group to address these two problems for several years.

Belinda has heard all of this before. She denies those allegations and the claims in his suit. She and the Stronach Group filed a countersuit against Frank alleging that his “imprudent and in some cases, fanciful schemes” and pet projects—including millions he sank into Adena Farms—threatened the viability of the company.

“I love my father. I love my family. The litigation is just sad. It’s very unfortunate,” she says. “I have a responsibility to do what’s right for my kids and my greater family. And that means running a business with good governance, one that could generate income for future generations.”

The Death Watch

After chatting for an hour in the conference room, Belinda suggests I take a golf cart tour of the track with her aide-de-camp, Aidan Butler, chief strategy officer and acting executive director of California racing operations for the Stronach Group. While he’s pointing out improvements the company has made, we pull up beside a crew installing pipes under the track, part of the new French drainage system, which is designed to handle heavy rain and flooding.

“This was something that was never thought of being used in Southern California—because they would never have imagined those sorts of downpours,” he says. “The chances of it happening again are very slim, but we’ve prepared as much as we can.”

Next it’s over to the onsite hospital, where a first-of-its-kind equine PET scanner will soon be installed, and then to the so-called Blue Room, where each of the 30 horses was euthanized with an injection of a barbiturate mixed with tranquilizers. Butler says he has been present for every killing since he was dispatched to Santa Anita after Battle of Midway was put down.

Everything changed after that death. More and more press and protesters began arriving, and fewer spectators. Eventually the Stronach Group was moved to act. They banned the use of riding crops in training. They brought in Dionne Benson, former executive director of the Racing Medication and Testing Consortium, and installed her in the newly created position of chief veterinary officer. In mid-March, in conjunction with the Thoroughbred Owners of California, they decided to phase out the use of the widely prescribed diuretic Lasix on race days, beginning in 2020.

They limited non-race-day therapeutic medications as well and mandated that they be administered only by track-verified vets. And the company began monitoring training at Santa Anita to make sure at-risk horses didn’t race, which is especially significant because the more horses a track runs, the more money it can make.

This represented an about-face. The Stronach Group had resisted pressure to shut down the track. They kept holding races until March 5, when the 21st horse was killed, after which they finally agreed to temporarily suspend racing. The company brought back a respected former track supervisor to repair the track surface and had an outside expert inspect the track, which he declared safe.

The day Santa Anita reopened, three weeks later, a surveillance camera recorded a trainer’s assistant giving a horse an illegal concoction known as a milkshake. Then, days later, a spectator recorded a video of a horse breaking its right front leg in midrace, falling and knocking down the horse to its right.

The latter video aired on the evening news, and protests mounted. Congresswoman Judy Chu called for congressional hearings. Senator Dianne Feinstein demanded that the CHRB halt racing at Santa Anita. The L.A. County district attorney launched an investigation.

The horses kept running and dying. In early June, following the 29th death, the top officials at the CHRB requested that the track suspend racing. The Stronach Group refused. The next day Governor Gavin Newsom instructed the CHRB to bar horses from running at the track unless they were deemed fit by independent veterinarians.

In just six days 38 were pulled from meets using the new protocol, and injuries decreased. But then, on June 22, on the final weekend of the Winter/Spring Meet, a horse named American Currency broke down during training and became the 30th thoroughbred to be euthanized.

The Big Bet

Belinda won’t say whether she has any regrets about the management of the track during the Winter/Spring Meet. “Hindsight is always going to be 20/20,” she says. When pressed, she deflects. “I think it’s about learning from the past and looking forward. What can we do to improve? That’s how I view it.”

By many accounts, her recent efforts produced results. “When Belinda started spending most of her time here, she took positive action,” says CHRB chairman Chuck Winner. “There has been significant progress.” Despite his criticism of the Stronach Group’s past management of the track, Rick Arthur agrees. “The events here at Santa Anita were a rude awakening for the people at the top,” he says. “Belinda made decisions that I think will have a long-term impact on welfare issues.”

Even PETA praises her recent moves. “We had been in discussions with the Stronach Group for years,” says the animal rights group’s executive vice president, Kathy Guillermo. “It took them a while, but they did a really good job of enacting meaningful rules after those deaths.”

Belinda is still waiting to hear the results of the district attorney’s investigation of Santa Anita, but in August the Breeders’ Cup announced that the track would retain its hosting privileges for the Cup—a vote of confidence in her reforms and upgrades.

Even before the Fall Meet began, another horse was fatally injured in training. Then, on September 28, Emtech, a horse with a history of medical problems, broke both front legs in a race on the second day of the Fall Meet, sparking new protests and questions about the Stronach Group’s management of the track. At press time the Breeders’ Cup was still scheduled to proceed, but a death at that event, everyone agrees, would be devastating for the Stronach Group and for horse racing in general.

At the end of the golf cart tour, we return to the conference room, where Belinda sits alone amid the untouched pastries. Horse safety at the Breeders’, she acknowledges, is important. “Certainly, we know the world will be watching Santa Anita,” but she says it’s also important that she focus on all future races at the track.

After a few pleasantries and a goodbye, she turns back to marking up slides for a PowerPoint presentation showcasing Santa Anita’s safety improvements. Then she looks up and says, “You will come back, won’t you?”

This story appears in the November 2019 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like