30 crazy weather facts you won't believe are true

Weird and wonderful weather

Tamas Kadar/Shutterstock

The world is a curious place and so is the weather. A hot topic of conversation wherever you are, our climate never ceases to surprise, delight and upset us.

From the wettest place on Earth to animals that can tell the temperature, read on for some mind-blowing facts about the world's weather you probably didn't know.

The wettest place on Earth is in India

Daniel J. Rao/Shutterstock

Disputed by several places in Colombia, the current official record holder, as recognised by the Guinness Book of World Records, is Mawsynram in East Khasi Hills in eastern India. With a long monsoon season and a short dry season, the average annual rainfall here is 467.4 inches (1,187cm) which is equal to a three-storey house in height. The neighbouring hamlet of Cherrapunji has also staked its claim for the record.

The United States has the most tornadoes

Huntstyle/Shutterstock

According to US Tornadoes, the United States experiences around 75% of the world's known tornadoes – that's an average of 1,253 tornadoes per year. Although tornadoes have been recorded in every US state, you're most likely to see one in Texas. With typically 146.7 tornadoes a year, the state has also experienced some of the worst in recorded history.

Wind is silent

S Curtis/Shutterstock

If you imagine a windy day outside, you're probably thinking of whistling and swooshing sounds that increase with the speed of wind. In reality, wind is silent until it passes through or comes into contact with an object. It can be either friction, rolling or rubbing that causes these sounds, but it's always the objects reacting to the wind that produce sounds rather than the wind itself.

There are 760 thunderstorms on Earth every hour

Anna Om/Shutterstock

There have been many attempts to calculate the number of thunderstorms happening on Earth, however, the data has always been inaccurate due to the complicated nature of gathering it. The number was finally calculated in 2011 thanks to more than 40 weather stations around the world that were equipped with machines able to detect electromagnetic pulses produced by strong lightning bolts. Curiously, the peak time for storms around the world is around noon GMT.

Raindrops are really fast...

twinlynx/Shutterstock

Although an estimation, most physicists agree that an average raindrop falls with a speed between nine and 10 metres per second, which is an equivalent to 22mph (35.4km/h). These calculations are based on a large raindrop (about 3/16in/5mm in diameter) and explains why rain, especially heavy rain, can erode soil so easily.

... they don't look like you think...

pernsanitfoto/Shutterstock

Even though we're used to seeing drawings and images of tear-shaped raindrops, that's not how raindrops appear in real life. With many factors, including gravity, air resistance and surface tension having an impact on the structure of each individual drop, they actually vary in shape. Smaller droplets are spherical, while larger drops have a more domed shape – almost like the top bun on a burger.

... and here's why they aren't bigger

A3pfamily/Shutterstock

When each individual droplet gets heavy enough in the cloud to fall, it accumulates other droplets it bumps into en route to the ground. But despite this, you won't find raindrops the size of basketballs falling from the sky. That's because of a number of factors, including the speed at which it falls. The bigger the raindrop, the faster it falls and the higher air pressure it has to withstand until eventually the air pressure overcomes the surface tension, splitting the drop into two.

The Mississippi River once froze over its entire length

Milen Mkv/Shutterstock

Setting temperature records that still stand to this day, many American cities experienced the coldest-ever temperatures in 1899, when four consecutive days of extremely harsh winter conditions swept across North America. Known by many names, including The Great Cold Wave and The Great Arctic Outbreak, February of that year was so cold the Mississippi River froze over its entire length. A similar event was recorded in the UK during the Great Frost of 1683-84, when severe weather meant the River Thames was completely frozen for two months.

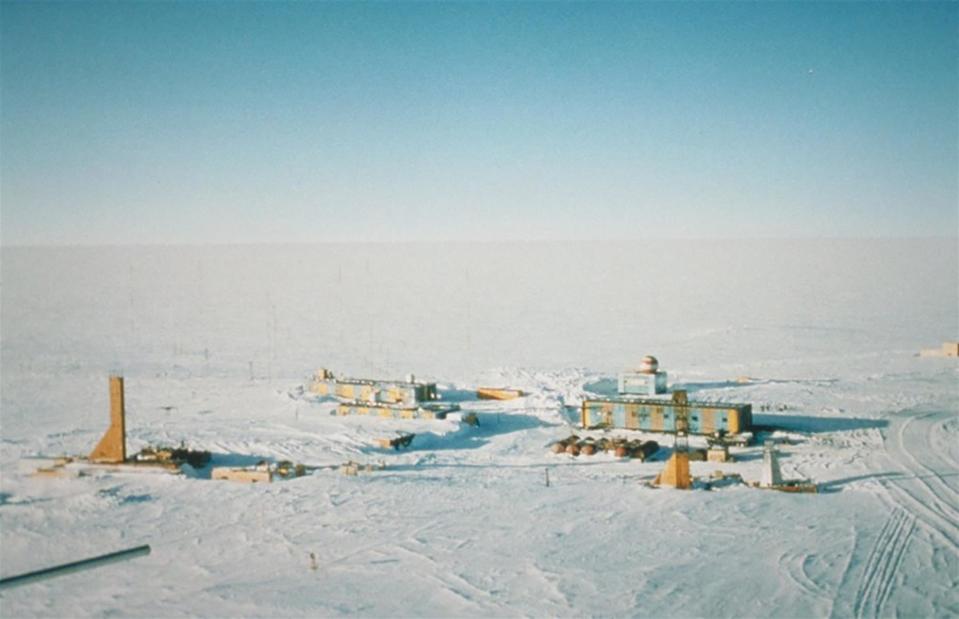

The lowest temperature recorded on Earth is -128.6ºF (-89.2ºC)

Todd Sowers/Wikimedia/Public Domain

Wrap up warm for this one. Measured at ground level on 21 July 1983, the coldest-ever temperature was recorded at the Soviet Vostok Station (pictured), a Russian research facility in Princess Elizabeth Land in Antarctica. Since then, the record has reportedly been broken by four degrees along a ridge between Dome Argus and Dome Fuji in Queen Maud Land in Antarctica. However, it was measured by a satellite and occurred at an elevation of 12,800 feet (3,900m) so it isn't officially recognised.

Yuma, Arizona is the sunniest place on Earth

Cheri Alguire/Shutterstock

According to the World Meteorological Organization, the sunniest place on Earth is Yuma in Arizona. Enjoying an average of 4,015 sunshine hours per year, the city has a total of 11 hours of sunlight in winter and up to 13 hours in summer. Rainfall here doesn't exceed 7.8 inches (20cm) per year but it also means that the temperature exceeds 40ºC (104ºF) for around 100 days a year, leaving Yuma feeling like a furnace.

Cricket chirps tell temperature

beatriz alejandra juarez/Shutterstock

In what is probably one of the more bizarre mathematical equations, temperature is calculated according to the rate at which crickets chirp. Formulated by Amos Dolbear in 1897, the Dolbear's law helps calculate the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit, based on the number of chirps per minute. The calculation is accurate within a degree and is measured by the chirps of a field cricket specifically.

Oymyakon is the coldest inhabited area on Earth

Spiridon Sleptsov/Shutterstock

Located in northeast Russia, a two-hour drive from Yakutsk, Oymyakon is the coldest permanently inhabited area in the world. The rural area experiences an average of -50ºC (-58ºF) during winter and is located in an extreme subarctic climate zone, which means that the ground here is permanently frozen (known as permafrost). Oymyakon's weather station has also recorded the coldest temperature in the Northern Hemisphere (-67.7ºC/-89.9ºF).

There's no official record for the hottest-ever recorded temperature

inazakira/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 2.0

It's widely accepted that the hottest-ever temperature (56.7ºC/134.1ºF) was recorded on 10 July 1913 in Furnace Creek Ranch, California in the Death Valley desert but the record has never been recognised officially. This is due to possible problems with the accuracy of the reading. It's difficult to calculate and record such a measurement as air temperature will change in the shadow while the ground temperature can exceed air temperature by as much as 50ºC (122ºF).

The first-ever weather forecast was published in Britain

elRoce/Shutterstock

Calculated by Admiral Robert FitzRoy, the very first daily forecast was published in The Times on 1 August 1861. Thanks to the invention of the telegraph, he had data on barometer, wind and temperature readings sent to his office every morning from various ports dotted along Britain's coast, which then allowed him to predict when and where storms would hit. It wasn't for another half a century that advances in the understanding of atmospheric physics led to the creation of numerical prediction – the basis of modern-day forecasting.

You can't actually smell rain

A3pfamily/Shutterstock

Most of us recognise the smell of rain as the earthy, musky scent that fills the air just before a rainstorm, especially in summer. In reality, rain itself doesn't have any smell. The scent so familiar to us – called petrichor – actually comes from the dry surfaces the rain hits. Every raindrop ejects tiny particles known as aerosols when it hits the ground. These particles consist of a combination of fragrant chemical compounds we can smell when they're inhaled.

Cooler temperature helps you think

MISHELLA/Shutterstock

Although the research is still very theoretical, it's now becoming widely accepted that colder temperatures help us think better. Similar research also suggests that warmer temperature impairs our ability to use our full cognitive power, making complex decision-making a lot harder. In simple terms, our body uses more energy to cool down than it does to warm up so in summer most of the glucose (our main energy source) is used to cool down while in winter there's a lot more leftover glucose for us to use for the brain's mental processes.

The Atacama Desert is not the Earth's driest place

Dale Lorna Jacobsen/Shutterstock

It is widely believed that the Atacama Desert, especially the Antofagasta Region in Chile, is the driest place on Earth, however, it isn't true. The McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica haven't seen any rain for almost two million years. The lack of precipitation and extremely low humidity means that even though they're surrounded by glaciers, the valleys are snow-free. The region is also one of the world's most extreme deserts with no living organisms found here apart from certain bacteria that live in the rock interior.

The foggiest city in the world is in Canada

Elena Elisseeva/Shutterstock

While southeastern parts of Newfoundland, Canada, are considered the foggiest in the world, it's St John's, also in Newfoundland, that can lay claim to the title of the foggiest city. It's shrouded in a thick fog for roughly a third of the year and is also Canada's windiest and cloudiest city. If you happen to visit as the fog is about to roll in, head to Signal Hill and watch the city be slowly swallowed by a thick curtain.

Around 26 feet (8m) of snow falls in the snowiest city on Earth

SARIN KUNTHONG/Shutterstock

With an average snowfall of 26 feet (8m), Aomori City in northern Japan is the snowiest city on Earth. During winter, it's not unusual to find yourself driving along walls of snow, however, locals have learned to embrace it and have several festivals to celebrate the unique weather conditions. The second-placed city, Sapporo, also in Japan, might be famous for its snow festival, but it experiences around 10 feet (3m) less snow than Aomori City.

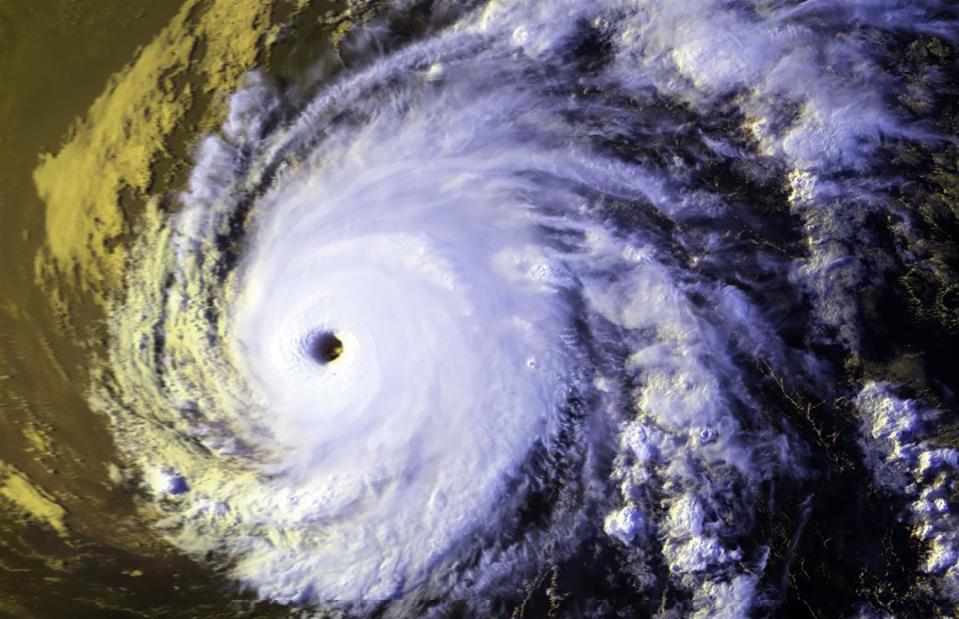

The longest-lasting tropical cyclone went on for 31 days

NOAA Satellite and Information Service/Wikimedia/Public Domain

August and September 1994 saw one of the most unique tropical cyclones ever experienced – Hurricane (also Typhoon) John. John travelled from the eastern Pacific to the western Pacific and then back to central Pacific, covering an astonishing 7,165 miles (13,280km). Because it existed on both sides of the Pacific, it's known as both a hurricane and a typhoon.

A town in France is one of the windiest in the world

Sasha64f/Shutterstock

Granted, the katabatic winds of Antarctica and the Roaring Forties winds (40-50 degrees south of the equator) that rip through the Pacific Ocean are both a force to be reckoned with, but there's a small fishing village in France that is pretty much constantly windy. Gruissan, located on France's Mediterranean coast, is a traditional fishing village that experiences winds over 18mph (28.9km/h) for an average of 300 days a year. Dominated by the Tramontane, a strong wind from the northwest, you'd be lucky to visit Gruissan when it isn't gusty.

A yodel can't cause an avalanche

canadastock/Shutterstock

Contrary to what we've seen in countless films and cartoons, yodelling and noise in general, can't trigger an avalanche. Research has shown that only the loudest sonic boom could potentially trigger an avalanche under the most sensitive conditions. Instead, avalanches are mostly caused due to weight changes after the weather and existing snow conditions are susceptible to an avalanche trigger. Snowfall, wind-deposited snow and even skiers and snowmobiles can apply enough pressure to cause an avalanche.

The longest recorded dry period lasted 14 years

Adwo/Shutterstock

Spanning 14 years – a total of 173 months – the world's longest drought lasted from October 1903 to January 1918. During this time not a single drop of precipitation fell in Arica in northern Chile.

A heatwave once turned grapes into raisins before they were picked

WineCountry Media/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

After a record-level heatwave descended on northern California during the first weekend of September in 2017, many Bay Area wine producers were left with grapes that had turned into raisins even before picking. Scorching temperatures of 38ºC (100ºF) and higher left the vines severely dehydrated and some of the state's most notable wine-growing regions of Napa and Sonoma faced uncertainty whether there would be enough grapes to harvest.

Hurricane Harvey changed rain maps forever

IrinaK/Shutterstock

With more than 30 inches (76cm) of rain falling in just a few days in southeastern Texas, the National Weather Service had to update its rain accumulation map with a new colour (lavender) to effectively display the graphics. On 27 August 2017, Houston alone received 16.07 inches (40.8cm) of rain, making it the wettest day in the city's history.

There is a record for greatest rainfall in a minute

Preservation Maryland/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Unionville in Talbot County, Maryland holds the record for experiencing the greatest rainfall in 60 seconds. Recorded on 4 July 1956, 1.22 inches (3cm) of rain fell in a minute. In comparison, Hong Kong experiences some of the worst sub-tropical rainstorms in the world, however, its black rainstorm signal will only be used to warn the public when rainfall exceeds 2.75 inches (7cm) in an hour.

Thunder and lightning are the same thing

Tamas Kadar/Shutterstock

Even though the light flash slicing through the sky and the following noise have two different names, they're technically the same thing – only one is to do with light and the other with sound. Due to the difference between the speed of light and the speed of sound, we see the flash first and only then hear the sound. First, light slices through air pressure in the atmosphere and we see lightning. It then retracts and the air pressure rushes back together, creating the thundering sound we're so familiar with.

Snow isn't actually white

Pixelcruiser/Shutterstock

Despite what our eyes are telling us, the white stuff isn't really white but rather translucent. When light reflects from the many individual sides of every snowflake, it's scattered in lots of directions, diffusing the entire colour spectrum and making it appear white to the human eye. Translucent Christmas doesn't sound that magical though, does it?

There's a snowflake catalogue

Bobkov Evgeniy/Shutterstock

No matter how much we'd like to believe that every snowflake is unique, there are actually 39 kinds of solid precipitation, including 35 that are snow crystals or flakes. Depicted in a graphic created by chemistry teacher Andy Brunning, who runs the chemistry blog Compound Interest, the snowflakes are categorised based on their individual properties. The graph also includes sleet, ice and hailstone.

It almost never snows in Antarctica

Steve Allen/Shutterstock

You might be very surprised to hear this, but it almost never rains or snows in Antarctica. It's actually a desert and a particularly dry one at that. For precipitation to happen there needs to be humidity and there's no humidity without heat – conditions that don't occur on the world's southernmost continent. When it does snow, the snow doesn't melt and is accumulated over thousands of years until it compresses and turns into ice.

Now check out the most significant weather event in every US state