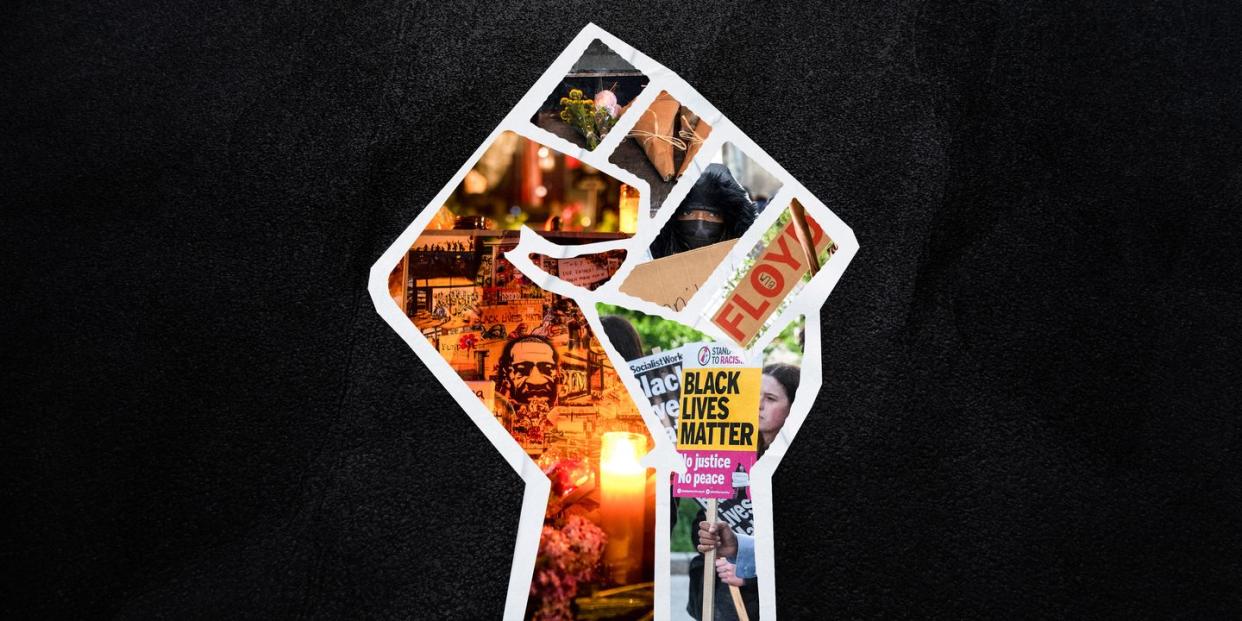

3 Years on From George Floyd’s Death, What’s Changed in American Policing?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Despite the outpouring of grief and disgust following the killing of George Floyd by members of the Minneapolis Police Department three years ago, 2022 saw the most citizens killed by police since a project called Mapping Police Violence started keeping track a decade ago. (The project doesn’t get into which have been deemed justified.) The city of New York paid out an astonishing $237 million in fiscal year 2022 to settle personal injury and property damage claims against the NYPD, according to the city comptroller’s office, and America’s biggest city is not alone in forking over gobs of taxpayer money to cover misconduct claims.

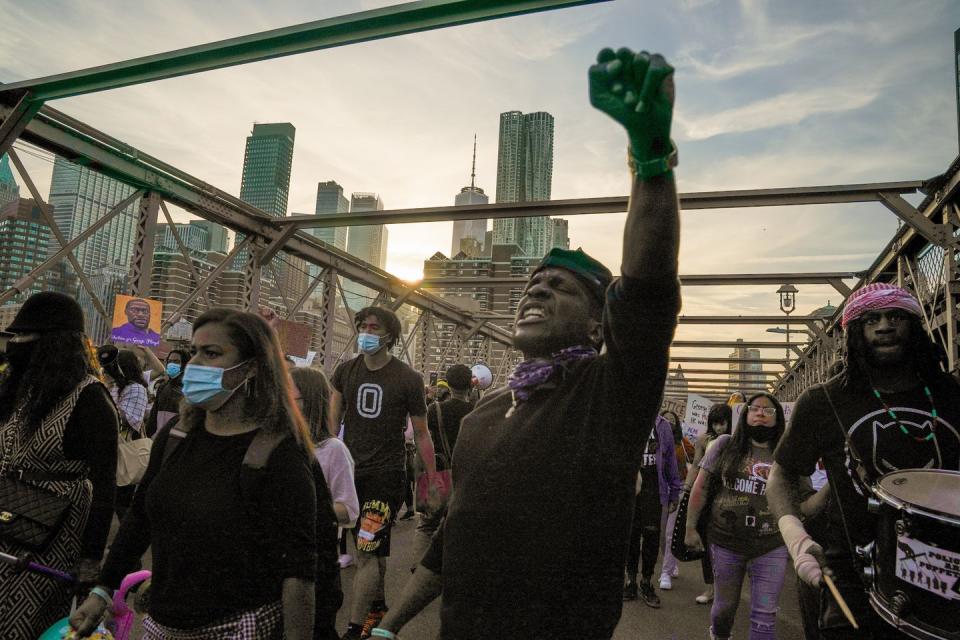

The protest movement that erupted in summer 2020 saw calls to address racial discrimination in policing and the use of force. There was even talk of reimagining the role police play, where professionals trained in social work or in responding to mental health crises could be dispatched to some calls, and some department funding could be reallocated to address some of the root causes of crime. So where do we stand three years later?

First of all, police by and large have not been Defunded. A few cities reduced budgets, but many that did so in 2021 soon reversed course amid rising crime rates and the political pressure that came with them. (Violent crime is now receding, though the picture does vary from county to county.) In some jurisdictions, overtime pay has grown substantially. Many cities have banned chokeholds, but only a few states have outlawed the kinds of “no-knock warrants” that led to the death of Breonna Taylor, and it complicates things that “American policing” is not a hugely useful term.

“You have 18,000 police departments. 90% of them are 50 officers or less,” says Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a Washington-based nonprofit police think tank. “And there's no central repository where you can get state-of-the-art best practices. No national standards, and no place to get them.” He cited bans on chokeholds. “[If] that’s all they do, that falls short of what that training should be,” says Wexler, once of the Boston Police Department. “When you have a use-of-force situation, and you can't use a chokehold, well, what are your other choices? Police reform can't [just] be about telling police officers what they can't do. Police reform needs to be telling police officers what they can do.”

At the root of our legal regime on police use of force is a case called Graham v. Connor, in which the courts established that force was justified if an officer had an “objectively reasonable” expectation of risk to his own safety or the safety of others. “Reasonableness in that context means, What would the average police officer do?” says Jeffrey Fagan, a Columbia Law School professor and director of the university’s Center for Crime, Community and Law. He says the same standard applied to New York’s “stop-and-frisk” policy, which a federal judge eventually tossed as unconstitutional in a ruling based in part on Fagan’s research. But there’s some movement now to replace the “reasonableness” standard with what’s called a “necessity” standard, led by a 2019 law in California called AB 392.

“The old standard was that the officer could use lethal force to overcome resistance to executing some kind of a legal process, a search or an arrest,” Fagan says. Now, in America’s most populous state, police can only use lethal force when it's necessary, and “‘necessary’ has a really interesting effect on narrowing the police use of lethal force.” We could start to assess a use-of-force case based on whether police could have found a different way to resolve the situation.

That last bit is what Wexler’s organization is working on at the National ICAT Training Institute, which opened earlier this month in Decatur, Illinois. “ICAT” stands for “integrating communication, assessment and tactics,” and Wexler proudly says the training is free through the end of this year for any police officers who can get themselves to Decatur. It’s a deescalation program that primarily focuses on how police interact with people who are not carrying a gun. “Knives, rocks, bottles,” Wexler says, “We think that we can reduce the officer-involved shootings in the non-firearm situations,” though the training deals with gun-wielding suspects, too. In his view, “we're living in a time of higher expectations and not sufficient training to meet those expectations.”

For a sense of the training gap, you can look at the Minnesota Department of Human Rights report on the Minneapolis Police Department—the same department at the center of the George Floyd killing—published in April 2022. It found that “MPD officers use higher rates of more severe force against Black individuals than white individuals in similar circumstances,” and that there is racial discrimination in traffic stops, when handing out citations, and much more. But the report also looks at how, while the MPD had updated its use-of-force policy more than once since Floyd’s killing, that didn’t translate to re-training the rank-and-file.

Officers were provided with a 15-minute narrated PowerPoint presentation, the report finds, and in some precincts, supervisors also provided a top-line readout of the policy changes. But officers told investigators that over a year after the new policy took effect, there was “no substantive training” for officers on the new policy, which prohibited neck restraints. The report finds department trainers are often not qualified and actually embed flawed principles in the training curriculum. To Wexler’s point, “officers expressed concern that they did not understand the updated Use of Force Policy, but MPD leaders expected them to follow it.”

The ICAT program is designed to rework the process of a police encounter well before you get to a chokehold situation. I asked Wexler for an example of the kind of de-escalation techniques involved. In standard police training, “they encounter someone with a weapon. If it's a knife or gun, their approach is to pull out their gun, aim it at the person, and shout, ‘Drop it! Drop it!’” he says. “What we say is, rather than taking out your gun and aiming and feeling like you have to do it as fast as possible, everything is the opposite of that. It's slowing things down, it's communicating, it's backing away, and it's getting cover. The idea is to resolve it without having to use force.” He says the standard training is one thing when applied to a bank robber, who might well drop the weapon. But it’s another thing if someone’s in a mental-health crisis and unable to grasp or comply with commands.

“Instead of using increasing force, this is about decision making. That's what they do in the United Kingdom. They don't rush in because they don't have guns.” That’s true of most British police and, for the most part, the British public. And that’s the 400-million-pound elephant in the room here: America’s 400 million civilian-owned firearms. We are very much not the U.K., not least because there’s a mass shooting somewhere in America most days of the week, and Wexler pointed out that while police are justifiably criticized when they use excessive force, they’re also criticized when they fail to use force quickly enough in an active-shooter situation. The Minneapolis report harshly criticized the “paramilitary culture” that the department fosters from the very first days of academy training, and that Warrior Cop mentality—which pits police against the communities they work in—has decimated relations between the two. But there are also times when we ask cops to be warriors.

For Wexler, it’s about training cops so they’re better equipped to make the right decisions. Because it’s usually police who respond to both an active shooter and someone in a personal crisis in this country. “It’s not enough for an officer to fear for their life,” Wexler says. “What are the other choices? That's the critical decision model.”

But the Minneapolis report indicates how difficult it is to follow through on any kind of change in just one department—and a department that was under serious spotlight at the time. “Because of the discretion that officers have in encounters, I honestly think the only way to truly limit uses of force is to limit police interactions,” says Puneet Cheema, manager of the Justice in Public Safety Project at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “The vast majority of calls that law enforcement actually respond to have very little to do with violent crime. I think some studies have shown it's 4% in some cities.” People dial 9-1-1 over neighborhood disputes, or because they see someone standing in the dark outside. “An officer shows up and then escalates an encounter,” Cheema says, “and then someone gets arrested.” The alternative is to dispatch social workers or “crisis response teams” to some calls, which cities like New York have begun doing here and there. Denver also has a program, and CAHOOTS in Eugene, Oregon has been around for 30 years.

The officer’s discretion is the key factor for Cheema. “It's rooted in Graham v. Connor, but also how Graham is interpreted,” she says, “And most uses of force and police interactions are never going to make it to court to be scrutinized in that manner. Most of them are interpreted by other officers, if they're interpreted at all. There are a lot of departments that don't even document uses of force. They simply commit them and move along. And people who are subjected to them often don't have enough power to do anything about it. They can file a complaint, but with whom? The law enforcement agency? Most that I've seen don't have great accountability systems. There's very little oversight when force happens.”

That Minnesota report found that “violating a policy is not a significant problem because MPD does not hold officers accountable when policies are violated.” Victims can win financial relief through lawsuits like many did in New York last year and elsewhere, usually through a Section 1983 civil rights claim. But officers are often personally shielded from liability thanks to “qualified immunity,” a standard created by the courts where police enjoy civil immunity so long as their behavior does not violate “clearly established” law.

Basically, if you’re suing, you need a (very) similar case to yours to have already happened sometime in American judicial history to clear the hurdle set up by qualified immunity, and in practice that rarely happens. The state of New York has moved to roll back aspects of qualified immunity, but in general not much has changed. It was a qualified-immunity provision that may have doomed the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act back in 2021, as Republicans and police unions mobilized against it claiming that police need the protections and that rolling them back would make it more difficult to recruit. In truth, police departments across the country are struggling to recruit, and one reason is that folks see the current environment as hostile to policing. “If you're a police chief in a medium-sized city and you need officers, you may very well look the other way about hiring a cop who's got a bad record from a neighboring state because you need boots on the ground,” Fagan says. Some departments are lowering hiring standards.

Qualified immunity concerns civil lawsuits. Police are not shielded from criminal charges, and they have been brought in the case of George Floyd’s assailant, Derek Chauvin, and others. It’s more common to see cops fired for misconduct, but the U.S. still has no centralized database for tracking these officers. This leads to so-called “wandering officers,” who can get a job as a police officer having been already judged unfit to serve by another department. Tamir Rice was shot by an officer named Timothy Loehmann whose previous supervisors had allowed him to resign after he showed a “dangerous lack of composure” during firearms training, and Wexler flagged this as a further problem: “What happens in some departments is, someone will be investigated and right before they're about to fire them, they will resign,” he says. Then it would be up to that department to tell anyone asking why the person had left. There’d be no real record of their de facto dismissal.

New York recently repealed a piece of state law shielding the misconduct records of public employees, including police, and Fagan thinks the transparency could help. “You can imagine the advent of police misconduct databases is something that would help identify bad cops,” he says. There’s also the notion of decertifying police officers following misconduct, and honoring that across state lines “so that a cop [decertified] in Ohio can no longer be employed as a police officer in Indiana.” But Cheema says it’s rare for things to get as far as a formal misconduct charge in the first place when compared to “the [number] of complaints that are dismissed without actually being fully investigated, or that are deemed not credible because they just take that an officer's word at face value.”

Police unions broadly oppose all this stuff as well, and that’s a big part of the equation. There’s political opposition and an intractability within departments as well. In 2019, Minneapolis banned “warrior-style training,” which communicates to officers that they’re closer to an occupying force in a war zone, surrounded by potential enemies, than peacekeepers working in a community. Yet the report found “much of MPD’s current trainings continue to embed this warrior mindset. As a high-level MPD leader explained, MPD currently uses a ‘paramilitary’ approach to train its officers.” The culture of an organization isn’t built by city-council decree.

Minneapolis banned Warrior Cop training on the basis that “when you’re conditioned to believe that every person encountered poses a threat to your existence, you simply cannot be expected to build out meaningful relationships with those same people.” Yet not only did the MPD continue to train cops on the warrior mentality, but also trainers told new hires that “instant and unquestioned compliance is in order.” The report found “this mentality of ‘unquestioned compliance’ is endemic within MPD’s organizational culture,” adding that “while maintaining a chain of command is important for a police department, a mentality of unquestioning obedience undermines MPD’s written policies—such as officers’ duty to intervene or duty to report unauthorized use of force.” This militarized mentality then leads to a more punishing response for officers who do step out of the Thin Blue Line to report or stop misconduct.

“Policing is a profession, like others, where peer-group pressure, one way or the other, makes a difference,” Wexler said. “And so you need to train officers in how to overcome what sometimes can be significant peer-group pressure to step in and do what's necessary to stop whatever is happening.” He cited ABLE (Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement), a bystander intervention training from Georgetown, but also admitted this approach dates back to Rodney King in 1991. Almost 30 years later, officers did not intervene on behalf of George Floyd, though they were charged and convicted for this failure to act.

“There's a reason we don't work on training at LDF,” Cheema says, and while she’s clear that accountability for misconduct is important to victims’ families, she is laser-focused on limiting the interactions between citizens and police. That means limiting traffic stops and dispatching specialists to deal with calls that involve mental and behavioral health issues, though there are situations where someone experiencing a personal crisis can pose a violent threat. In the end, this approach could free up American police to solve more crimes. About half of the murders in this country go unsolved, the worst rate in the industrialized world. Germany clears well over 90% of theirs. It doesn’t seem like our system is really working for anyone.

You Might Also Like