3 Women on How They Live With COPD

Unless you know someone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a condition that includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis and restricts breathing and airflow, it can be hard to understand how the health problem impacts daily life. While no experience is universal—16 million Americans have COPD, and with varying levels of severity—the common thread is that a diagnosis results in changes big and small. Here, three women share how they manage the disease and continue to lead full and fulfilling lives.

“I Find Purpose By Getting the Word Out.”

Midge Wilson, 60, a retired nurse in Orlando, Florida

Up to 90 percent of people with COPD smoked or were exposed to secondhand smoke. Wilson falls into that second category. “Our grandparents lived with us when we were growing up, and my grandfather was a chain smoker,” she says. “As a result, all of my siblings have asthma. Mine progressed further, and I was diagnosed with COPD in my late 40s.”

Soon after her diagnosis, Wilson started using oxygen—delivered from a nose piece connected to a tank—to sleep, and when she was especially active during the day. “I get shortness of breath, so I always have an inhaler with me when I leave the house,” she says. “And sometimes I need to sit when I get home for a few hours with oxygen until I can breathe normally on my own again.”

This is a drastic shift from how her life was before COPD. “I was a nurse and used to work from 4am until 6pm. I had to let my work go; it just got to be too much,” she says. Wilson was also a weightlifter and won trophies in strength competitions. “I first went to the doctor when I noticed getting the empty bar off the rack was hard,” she says. “COPD ultimately forced me to cut that kind of exercise out of my life.”

The changes since her diagnosis haven’t all been about loss, however. Wilson is now devoted to spreading COPD awareness. Since 2018 she’s worked as a patient advisor for the American Lung Association, sharing her first-hand knowledge of the disease. “I also go up to teenagers smoking and tell them about what being around smoke did to my lungs,” she says. “I say that there are days I literally can’t breathe because of someone else, and you have the choice to stop.”

“I Arm Myself With the Tools to Do What I Love.”

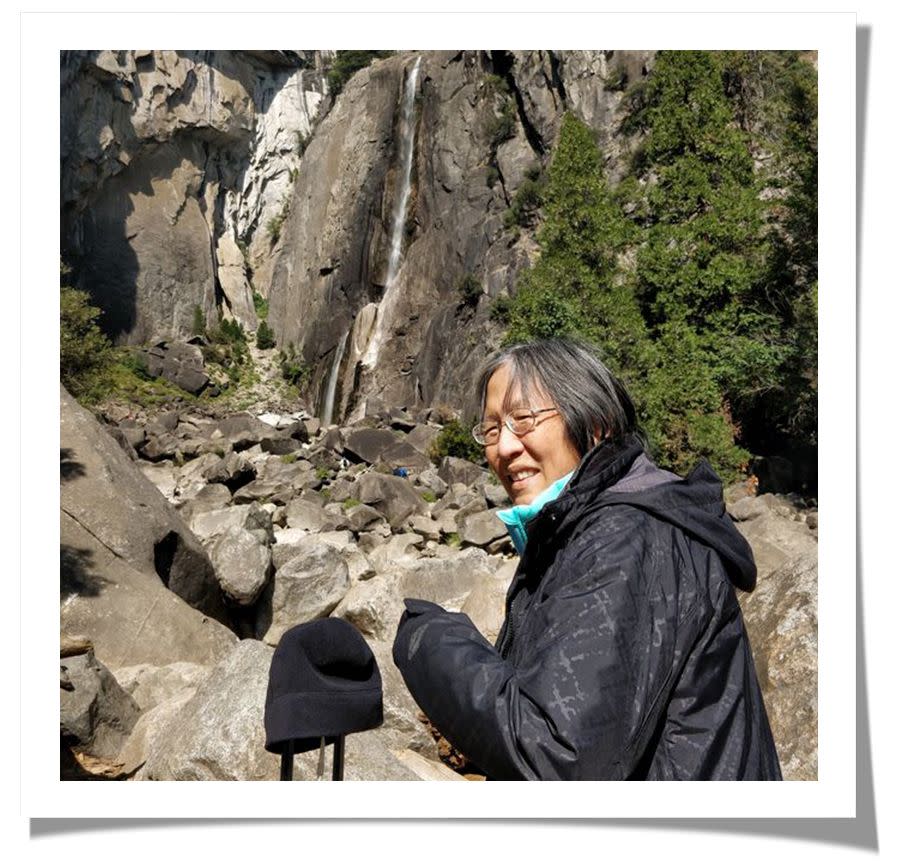

Valerie Chang, 63, the head of a nonprofit in Oahu, Hawaii

Twenty-one years ago, at age 42, Chang was sitting around a campfire with her daughter’s girl scout troop and mentioned she was having trouble breathing. “The troop leader told me I had to get it checked out because I was young and physically fit, and that wasn’t normal,” she recalls. Chang ultimately got a pulmonary function test done and discovered she was exhaling one third the normal amount of air. “I was sent to a lung specialist, and he told me that I had severe lung disease, even though I’d never smoked in my life,” she says. “My doctors don’t know why, but I’d developed severe emphysema and chronic asthma, two diseases under the umbrella of COPD.”

Calling this diagnosis a shock is an understatement. “I felt destroyed and devastated, as if my world had ended,” she says. “I did an internet search for everything I could find about COPD, and it was all so depressing. Some articles said I had a chance of living maybe five years, and if I could get a lung transplant, five more.” This was unacceptable to Chang. “My children were 10 and 12 at the time; I wanted to watch them grow up,” she says.

What actually happened was far from these worst-case internet scenarios: With the right medications, Chang’s condition has not progressed in the two decades since her diagnosis. “I take three different inhalers, and they’ve kept me very stable,” she says. “I still have flare-ups one to four times a year, but I’ve never been hospitalized for my lung disease.”

She hasn’t let COPD hold her back either. “I got a part-time job as a judge, where I would sometimes have to talk for up to eight hours at a time—and I could do it!” she says. She also started a nonprofit, the Hawaii COPD Coalition, and became the Vice Chair of the U.S. COPD Coalition.

While she no longer goes out for half-mile swims like she did before COPD, Chang stays as active as she can. “Our kids bought me a water rower for Christmas. I put a portable oxygen concentrator next to me, place the tubing in my nose, and row away,” she says. And before COVID-19, Chang would still travel 25,000 to 30,000 miles a year for work and pleasure, bringing her portable oxygen with her. “Traveling and dining out are my joys,” she says. “I make sure I have the tools I need to have a full life.”

“I Changed My Lifestyle—and Changed the Course of My Disease.”

Jean Rommes, 76, a retired president and CEO of rehab facilities in Des Moines, Iowa

After reading a magazine article about COPD in 1985, Rommes had a gut feeling that she had the disease. She was a smoker, and would get winded climbing a flight of stairs. Still, it wasn’t until 2000 that she was willing to go to a doctor and get confirmation. “I had quit smoking by that point, but I would get out of breath just walking with other people,” she says. When she got the diagnosis, Rommes says she wasn’t surprised, but she also didn’t want to hear it. “So, I did what a lot of people with a COPD diagnosis do: nothing.”

For the next three years, Rommes fell into a depression and let her health go, and she gained close to 100 pounds. Then, a hospital visit in 2003 for chronic respiratory failure scared her into action. “I was lying in the hospital bed, and I was still out of breath,” she says. “My husband was starting to show early signs of Alzheimer’s disease, and I knew that I needed to be around to take care of things.”

Her doctor told her that losing weight would help—the more you weigh, the more oxygen you need to get around—so Rommes set to it. She bought a treadmill, walked regularly on an incline, watched what she ate, and dropped 100 pounds in 18 months. This set off a chain of positive reactions that changed the course of her COPD.

“I was able to go off oxygen completely for almost 10 years, and now I use it purposefully, like when I am exerting myself or traveling,” she says. While her lungs will never be in perfect condition, Rommes says that she feels good, and her disease isn’t limiting her. Before the pandemic, Rommes traveled to attend COPD Foundation meetings (she is on several of their committees), visited her three children and five grandchildren, went out to eat with friends, and was active in her church. There are things she chooses not to do, such as traveling to high-altitude places because it makes breathing difficult, and sometimes she has to come up with solutions, like renting a scooter if she gets out of breath walking around a huge convention center. But ultimately, she says, “I don’t feel like I miss out on anything because of COPD.”

You Might Also Like