The 25 Best True-Crime Stories of All Time

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

True-crime fandom may be booming, but that doesn’t mean that our cultural fascination with evil and transgression is new. Most innovations in media have taken up notorious crimes as a favored subject, from the cheaply printed broadsheets of the 18th century to the serialized magazines of the Victorian era to the cable TV networks of the 1990s. Now tales of crime and punishment inspire internet forums, podcasts, and streaming miniseries.

The creators of true crime, and the fans who consume it, will always exist in an ethical gray zone. Haters of the genre complain that it’s voyeuristic, intrusive, and crudely sensational, and they have a point. Defenders maintain that the best true crime illuminates dark corners and instigates change—even, sometimes, saving lives. They have a point too. What began in penny dreadfuls has evolved as it has flourished. Yes, some of today’s true crime doesn’t rise above lurid sensationalism. But the best of it exhibits sensitivity, intelligence, and empathy—while still tapping into the primal narrative power of the crime story.

As we created this list, we debated: What do we love about true crime? Despite the genre’s reputation for lingering over bloodshed and horror, crime engages every facet of human nature. Sometimes we relish the panache, the sheer nerve, of the master con man. Sometimes we marvel at the unfathomable callousness of the killer. There’s the baffling docility of Charles Manson’s followers, the spirited eccentricities of participants in a scheme to defraud McDonald’s, the dangerous hubris of “experts” who will put a defendant away based on pseudoscience. There’s even the courage of an attorney fighting against the odds to save clients crushed by an unfair criminal justice system. True crime does, from time to time, showcase the good guys.

You may notice that some long-celebrated works of true crime—or your own personal favorites—do not appear here. Some works, even from this millennium, did not hold up to our current standards for true-crime reporting, or for how to characterize victims and perpetrators. Some works were left out because we feel that another work sheds clearer light on a particular crime. We aimed to encompass the spectrum of wrongdoing with this list, but in the end, not everything could fit. And of course, as with any human endeavor: A lot of true crime is just bad.

The ugly aspect of the true-crime boom—the lazy, flippant podcasts; the exploitative and dishonest docuseries (e.g., the Investigation Discovery channel in toto); the rabid fan base of amateur internet sleuths—is undeniable and deplorable. But it is not damning. It’s a reflection of true crime’s power, the flip side of the genre’s ability to move and inform—and sometimes even to change the world.

A killer takes a life, the authorities jail an innocent person, a political movement decides that the ends justify the means, a man steals a rare flower. Each of the stories we’ve chosen for this list hinges on a person or persons violating the social order, breaking the bonds of the civic and human community. And all of these stories ask what, if anything, can be done to make things right. In some instances, they end with justice delivered, a demonstration of how things can work out. And stories about unsolved crimes, like several of the masterpieces listed here, stoke the demand for answers and fuel investigations. Each tells us something about the nature of the world and the fabric of our social order, helping us peer beyond the limits of our own experience into the darkness.

Written by Truman Capote

Midcentury crime reporting tended to read either as a dry litany of facts or as sensationalized claptrap. Then came In Cold Blood, and suddenly reporting on murder could be an art. Originally published in four parts for the New Yorker, Capote’s tale of a grisly murder on a Kansas farm offered exquisite, meditative insight into the minds of killers and the community upended by their violence—a far cry from “If it bleeds, it leads.” Capote called the book, an instant sensation, a “nonfiction novel”; now you’re likely to find it shelved in creative nonfiction, a genre that Capote arguably created. Today the manipulative tactics Capote likely used to get sources to speak to him, and his blurring of the line between fact and what reads beautifully on the page, would give most 21st-century magazine editors pause. But the book still sings, and its influence can be felt everywhere: TV’s antihero obsession, the depth of detail in documentaries like The Staircase, the insertion of the reporter into the story as in Serial. In Cold Blood made true crime a personal endeavor and a literary feat—for better or for worse.

Created by Phoebe Judge and Lauren Spohrer

Created by public radio veterans interested in the experiences of “people who’ve done wrong, been wronged, or gotten caught somewhere in the middle,” Criminal tells a new story in each episode. As a result, it casts the net of “true crime” wide and creatively, with consistently fascinating and enlightening results. Recent subjects have included the disappearance of two endangered wolves; the first house in the U.S. to be legally declared haunted; a man who walked into a police station to confess to a murder committed 17 years earlier; and what it was like to grow up as the child of two prisoners serving time for helping the Black Liberation Army rob an armored car. Each episode is built from interviews, many conducted on location in places ranging from the Florida Everglades to the English countryside. In a podcast landscape full of padded, serialized true-crime narratives and tipsy hosts rehashing Wikipedia entries, Criminal—still going strong in its 10th year—stands out for its professionalism, compassion, integrity, and imagination.

Directed by Jean-Xavier de Lestrade

A group of French documentarians were given extraordinary access to the defense team and courtroom during the trial of Michael Peterson, a North Carolina novelist accused of the 2001 murder of his wife Kathleen. Exquisitely edited down from untold hours of footage, the first eight episodes became one of the most admired documentaries of its time, an exceptionally intimate look at how a criminal defense is conducted, as well as how a trial affects the accused’s extended family. Years later, when developments warranted, de Lestrade tracked the case’s twists and turns in five more episodes. (Skip the HBO dramatized version starring Colin Firth; it unfairly impugns the integrity of the documentary team.) Peterson’s is a seemingly simple case that entails coincidences that may not be coincidences and evidence that cannot be accounted for by either side’s version of what happened, making The Staircase a decades-spanning whodunit that has generated endless debate. That lingering mystery has a primal power to hook viewers, but in essence The Staircase is a portrait of how the American legal system works: a dramatic conflict between two disparate stories, each vying to be declared the truth.

Created by Jason Moon

Podcasting may have delivered a glut of true-crime content, but the medium doesn’t always lend itself to the genre. Without the arresting visuals of a televised documentary or the page-flipping appeal of a book, podcasts can feel weighed down with repetitive exposition or, worse yet, become a confusing cluster of names and timelines. But Bear Brook, produced by New Hampshire Public Radio, takes the challenges of telling its story of multiple murders across decades and makes that its strength. Beginning with the discovery of two bodies in a barrel in a remote woodland near Bear Brook State Park, the show could have easily teased us right away with “But there’s more to the story.” Instead, Moon lingers with his characters, immersing the listener in the story of this barrel, the town, and its people, before kicking you in the chest with the discovery of a second barrel. The result is a true master class in evidence and criminology reporting, untangling a web of genetics and genealogy in an effort to bring peace to the families of the four unidentified victims.

Written by T. Christian Miller and Ken Armstrong

This incredible piece of reporting, a partnership between ProPublica and the Marshall Project, is framed around Marie, an 18-year-old former foster kid and rape victim who was coerced by police in her small Washington state town to recant her story. “Unbelievable” provokes outrage in its portrayal of the shocking way poorly trained police officers can, and do, treat victims of heinous crimes. But “Unbelievable” is also the story of two dedicated women detectives in Colorado determined to crack the case of a serial rapist in their neighborhoods. The two narratives are intertwined, until straightforward, dogged police work solves the Colorado crimes—and brings justice for Marie. The ending, and the piece, is a triumph—a reminder that true crime isn’t only about evildoers. Great reporting and writing can and should focus on, and humanize, the victims of crime and the investigators who try to help them.

Written by Ann Rule

Rule befriended Ted Bundy in the early 1970s, when she, a divorced mother of four supporting her family by writing hard-boiled crime stories for True Detective magazine, and he, an articulate college student, worked the night shift together on a suicide hotline. A few years later, she learned that Bundy had been arrested for the kidnappings and murders of young women in multiple states and was suspected of a string of unsolved Seattle crimes she had been contracted to write a book about. At first, Rule found it hard to believe that her thoughtful, cultured young friend could be a murderer; The Stranger Beside Me is an account of her eventual acknowledgment of his guilt. It also launched her career as a true-crime master, specializing in stories like Bundy’s, in which seemingly respectable middle-class professionals are revealed to be the perpetrators of unspeakable crimes. Instead of the degenerate misfits and thugs portrayed in True Detective, Rule wrote books about men (and some women) her readers could easily imagine as neighbors, friends, and even lovers. Anyone could be a murderer, and it became part of the true-crime writer’s task to figure out how and why. Although the psychological terms in many of Rule’s books now seem outdated, by considering the criminal’s inner life at all, Rule changed the genre forever—and while she was at it, she brought true-crime writing a huge new audience of women.

Written by Michelle McNamara

Bad things can happen when amateurs decide to play detective. Look no further than the immediate aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing, when armchair sleuths identified the wrong man on Reddit as the bomber. Those types of internet detecting gone wrong are the rule. But McNamara’s quest to find the Golden State Killer is the exception. Meticulous, thorough, and above all unobtrusive to the police investigation itself, McNamara traced leads, tried out theories, and communicated with other obsessives who couldn’t stop thinking about the case. Her book documenting her search should be aspirational for all true-crime writers—a textbook in how to toe the line between being invested and being careful. But even leaving aside McNamara’s own tragic end—she died in her sleep before finishing the book—her descriptions of her “Talmudic study of police reports” and admission that the case consumed her should serve as a warning for others who dive into tragedy. It’s not a game of Clue. The crimes are real, and investigations can overtake you if you aren’t careful.

Written by Robert Kolker

A persistent complaint about the true-crime genre is that it glamorizes killers, obsessing over the details of their crimes and personalities while the victims are essentially forgotten. When Lost Girls—about the Gilgo Beach serial murders—was first published, this was impossible: The investigation into who had concealed several bodies in the scrubland along a Long Island highway had apparently stalled out, unsolved. Instead, Kolker focused on the women who seemed very evidently to be victims of a single murderer. They were sex workers but also daughters, sisters, girlfriends, mothers. They led complicated, difficult lives that offered them few options despite their individual talents, hopes, and dreams. After their bodies were discovered, their fractious families banded together to publicize the investigation, despite an often callous and indifferent media and the incompetence and corruption of the Suffolk County Police Department. “A missing girl is missing only to the people who notice,” Kolker writes in Lost Girls. In the long, dark period between their disappearance and the arrest of the alleged murderer in July 2023, Lost Girls helped make sure no one would fail to notice these women.

Written by Elizabeth Williamson

Fatal school shootings remain a signature American crime, a symptom of our national addiction to firearms and rage. No school shooting is more notorious than Sandy Hook, in which a mentally ill 20-year-old killed 20 elementary school children and six adults who worked at the school. But Williamson’s book is not exactly about the shooting. It’s about the wrongs committed afterward. Sandy Hook was so horrific it created real momentum for gun control legislation, and as a result, a right-wing disinformation campaign was launched, led by the radio personality Alex Jones. Williamson follows the travails of the victims’ parents as they attempt to achieve some social good as a result of their tragedy, only to be met with accusations that their children had never existed, or had not really been killed. This is a story that naturally provokes ire, but Williamson keeps her cool, meticulously documenting the ordeal of the parents and Jones’ long career of lies and hucksterism. Equally troubling, though, are his followers and minions—like a Tulsa woman who says the grieving parents “just rub me the wrong way”—and the social media platforms that did nothing to stem the viral conspiracy theories. Increasingly in our connected world, a terrible crime can be followed by terrible cruelty; Williamson’s story feels more urgent by the day.

Directed by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky

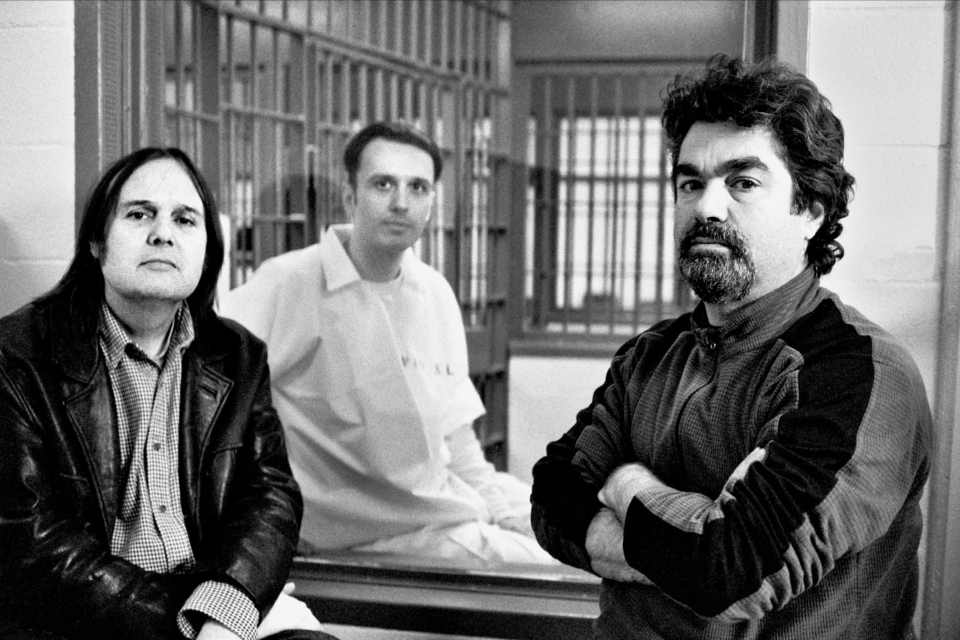

To watch the first film in the Paradise Lost trilogy now is to lament what documentary filmmaking has become in 2024. That’s because Paradise Lost represents the form at its purest. No filmmakers on screen, no metacommentary, no fancy lighting, no styling. Just cameras on subjects. Traveling to West Memphis, Arkansas, in the wake of the terrible murder of three 8-year-old boys, filmmakers Berlinger and Sinofsky wrangled access not only to the teenagers accused of murdering them, but also to the families of the suspects and the victims, and even the prosecutors and defense attorneys who were part of the initial prosecution that sent the “West Memphis Three” to prison. The untrammeled access is stunning, as is the filmmakers’ refusal to intervene, even as they become part of the story: The first film spawned a small, committed national movement to free the young men, the work and ultimate success of which is captured over the following two movies. Together, the Paradise Lost films are a remarkable, unglossed look at how the American justice system failed—and, ultimately, sort of worked—as well as an intimate portrait of one struggling community ripped apart by an indescribable tragedy, then ripped apart again by lazy police work, reckless prosecution, and widespread paranoia.

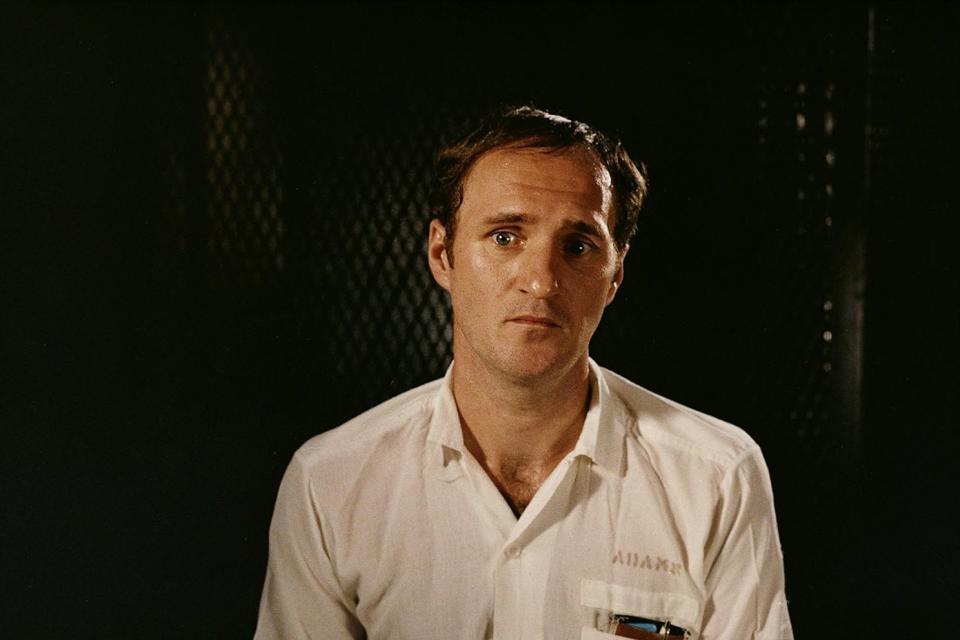

Directed by Errol Morris

It’s the rare true-crime work that both freed a wrongly accused man and revolutionized its art form. Morris’ elegant documentary persuasively makes the case that Randall Adams, a man serving a life sentence in Texas for shooting a police officer in 1976, was in fact innocent, and that another man had committed the crime. A sensation when it was released, The Thin Blue Line was disqualified from the Academy Award for documentary film because Morris’ use of reenactment scenes was frowned upon by traditional documentarians. In retrospect, reenactment proved to be a dangerous innovation that would be exploited by less scrupulous directors in the future. But the highly stylized nature of Morris’ reenactments—which include slow-motion interludes and film noir cinematography—work because they encourage no confusion with his more straightforward interview scenes. These scenes are abstractions—images not of what happened but of how to think about it. They illustrate how Morris evaluated various witness testimonies, weighing them against one another and the physical evidence. No relativist or postmodernist (as some critics have claimed), Morris believes in irreducible facts. To determine them, he made a powerful, intelligent work of art that is also a quest for objective truth.

Produced by American Public Media

The second season of In the Dark, which followed the relentless and almost ritualistic prosecution of a poor Mississippi man for murders he did not commit, is seared in the memory of every person who has listened to it. Host Madeleine Baran relocated to Mississippi to tell the heartbreaking story of Curtis Flowers, who was tried six different times for the crime of shooting four people inside a furniture store—resulting in 23 years behind bars, most of them on death row in one of the most notoriously awful prisons in the country. Baran sensitively captures the grief of Flowers’ family, who never gave up on him. On the other side of the story sits District Attorney Doug Evans, and Baran tirelessly investigates the absolute arrogance that led the D.A. to deprive Flowers again and again of justice, and the broken legal system that aided him in his ferocious vendetta. Originally just 11 episodes, the season expanded as the case evolved, culminating in Flowers’ release in 2020. In a sea of true-crime podcasts, In the Dark stands out for its mission: not just to explore an injustice and document our dysfunctional judicial system, but to keep pushing until that injustice is corrected.

Written by Susan Orlean

You probably remember that Charlie Kaufman’s movie Adaptation was adapted, sort of, from Orlean’s book The Orchid Thief. But that book was an expansion of “Orchid Fever,” a basically perfect example of the comic, exuberant, sneakily profound true-crime magazine story. Orlean’s writing vibrates at a frequency to match its subject, the twitchy, obsessive horticulturalist John Laroche, who runs afoul of the law after collecting incredibly rare ghost orchids. From the beginning, we assume that it’s going to go bad for Laroche, who “has the posture of al dente spaghetti and the nervous intensity of someone who plays a lot of video games”; he’s just that kind of guy. But even that pall can’t darken Orlean’s uninhibited prose as she navigates through a Florida swamp we’ll never visit with a dude like no one we’ll ever meet to find a flower we’ll most likely never see in real life. (These are not normal orchids!) Sure, the stakes are low; for his literal trespasses, Laroche pays a fine and gets probation. But the ride-along is an absolute high—a goddamn delight.

Created by Alex Goldman and PJ Vogt

Scam calls are extremely, annoyingly common these days. But in 2017, they were novel enough that receiving just one sent Reply All host Goldman on a mission to understand where it came from. No surprise: The robo-voicemail claiming that Goldman’s “iCloud has been compromised” was not from Apple, and his iCloud was just fine. Chasing down the message leads Goldman to develop an almost obsessive relationship with a call center employee named “Alex Martin” and ultimately takes him all the way to Delhi—where he and a producer attempt to visit the actual storefront where the call originated. The whole thing is a romp; you’ll marvel as Goldman relays the story to co-host PJ Vogt, and laugh at the absurdity of Goldman sweating through the streets of Delhi, finding periodic refuge at Starbucks. Of course, he can never truly crack the case! This wholly modern, international crime exists because of super-shady perpetrators operating across the barriers of distance, culture, and anonymity. But then, three years later, in a surprise episode, the real “Alex Martin” is revealed, and we get the full backstory of how and why young Indians end up trying to scam Americans out of a couple hundred bucks. The result is a deeply weird, engaging, and surprising investigation of a singular type of crime that just about all of us fend off every day.

Listen: Part 1 | Part 2 | The Real Alex Martin.

Directed by James Lee Hernandez and Brian Lazarte

While it’s easy to think of the Mafia as being all about murder, drugs, and probably prostitution, mob life is really about obtaining money and power by any means possible, no matter how unglamorous. (There’s a reason Tony Soprano works in “waste management.”) True-crime Mafia stories often lose sight of that fact, but the HBO documentary series McMillions seizes on it with gusto. McMillions tells the story of the McDonald’s Monopoly promotion and how, in the 1990s, the Mafia exploited a trick to cheat the game, cashing in ill-gotten Monopoly pieces for almost a decade, reaping millions of dollars. (Before the series, a 2018 Daily Beast story brought the case to a wide audience.) Directors Hernandez and Lazarte recognize that a con like this requires a level of skill and artistry that, in this case, was matched by the intricate sting operation the FBI used to catch the perpetrators, and the result is wildly entertaining. They’re aided by a colorful cast of characters, from archetypical brass-and-crass mob wife Robin Colombo to FBI agent Doug Mathews, who you’ll swear is actually part golden retriever. It all adds up to a madcap yarn that seems too wild to be true. But it is.

Written by Yepoka Yeebo

The pitch has become so familiar it’s almost a joke: There’s a pile of money I can get access to, but I need a little upfront cash so I can travel to the bank, or pay my lawyer, or resolve an outstanding fee. If you chip in, I can reimburse you a hundredfold. Just send me your bank information, and we’ll be in business. British-Ghanaian journalist Yeebo recounts the life and exploits of one of the great masters of this scam, known as advance-fee or 419 fraud: John Ackah Blay-Miezah. A Ghanaian smooth talker, Blay-Miezah convinced an astonishing array of wealthy and influential people in Africa and the U.S. that with a little help from them, he could liberate a fortune deposited in a Swiss bank by his country’s late president. Yeebo seamlessly moves from the fun of a classic con-man yarn—Blay-Miezah struts through these pages in his tailored suits, pulling on fancy cigars in luxurious hotel rooms from which he will evaporate when the bill comes due—to an equally engrossing history of the West African state and its rocky path to postcolonial independence. Her sharpest point: that Blay-Miezah succeeded so handsomely by exploiting the stereotype of Africa as a source of ill-gotten wealth, ripe for the picking.

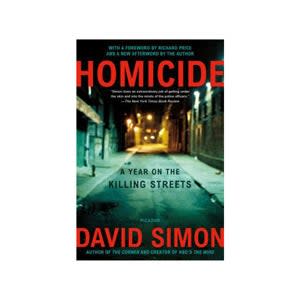

Written by David Simon

True-crime stories often get so wrapped up in dramatic individual cases and characters that they forget about the institutions, the machine that solves (or doesn’t solve) crime. That’s what makes Simon’s Homicide so unique and revolutionary. This book, the result of a year’s worth of daily reporting inside the Baltimore Police Department, doesn’t just follow one cop or one case, but delivers an inside look at all the arms and legs of a homicide division. In Simon’s immersive writing you can smell the blood and bad coffee, hear the cries of victims’ families and the groans of overworked sergeants. In today’s cultural climate, some might be inclined to dismiss Homicide as copaganda, but Simon is brutally honest in his depictions of the cops, never shying away from some officers’ casual racism, jaded outlook, and, at times, outright bad police work. Homicide begot a remarkable TV show, and after it The Corner and The Wire and, in some ways, Oz and Mindhunter and True Detective. You really can’t begin to understand what investigating dozens of murders a year does to a cop—or what experiencing hundreds of murders in a year does to a community—until you’ve read Homicide.

Written by David Grann (“Trial”) and Pamela Colloff (“Blood”)

Each of these stunning feats of reporting debunks a type of expert testimony that has put innocent people in prison for crimes they did not commit; we’re pairing them because together they show the power of true crime to affect the nuts and bolts of the criminal justice system. Grann’s devastating article tells the story of Cameron Todd Willingham, a poor Texas father of three who was convicted of—and eventually executed for—the crime of setting his house on fire and killing his three children. Grann heroically dismantles the infuriating, flimsy case against Willingham, especially its dependence on “expert analysis” of flame patterns in the remains of his home. This kind of analysis, Grann reveals, is endemic in arson trials—and incredibly subjective and misleading. In “Blood Will Tell,” meanwhile, Colloff details the case against Joe Bryan, a beloved school principal in a tiny Texas town convicted of killing his wife, Mickey, in 1985. Here the culprit is “bloodstain-pattern analysis”—a questionable type of forensic science that is widely used in cases even today. The piece had impact: Although the parole board’s deliberations are confidential, it’s surely no coincidence Bryan was finally released from prison in 2020, at the age of 79. Bryan can’t get that time back, and Willingham is gone forever. But these investigations restored their good names—while showing that true crime can interrogate the tricks and traps prosecutors often use to steal defendants’ freedom.

Read “Trial by Fire” at the New Yorker | Read “Blood Will Tell” at ProPublica.

Written by Bryan Stevenson

In the 1980s, as a freshly minted graduate of Harvard Law, Stevenson went to work defending poor Southern clients who had been wrongly convicted of crimes, as well as guilty clients serving draconian sentences. His memoir Just Mercy offers a stark, heartbreaking corrective to the valorizing of the criminal justice system in pop culture. His clients are the victims of police officers and judges who are racist, classist, and just plain lazy. Running all through Just Mercy is a single narrative, the story of Walter McMillian, a Black Alabama man wrongfully convicted of murdering a white woman, and the havoc that conviction wreaked on his family and community. Despite its focus on legal battles, Just Mercy includes some good old-fashioned detective work, as Stevenson and his team investigate the murder themselves in order to clear McMillian’s name. Unlike crime fiction, whether on film or in print, true crime is far less likely to treat the police and courts as heroic, diligent, or infallible, but no list like this one would be complete without a serious consideration of the many ways law enforcement goes wrong, as seen by someone working inside the system.

The saga of former football star Simpson’s pursuit, arrest, and trial for the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ronald Goldman has spawned any number of adaptations, from bestselling books to tawdry TV movies to a starry Ryan Murphy series to an eight-hour documentary that won an Oscar. But none of them compare in intrigue, in spectacle, and in drama to the trial itself, a kind of proto–reality show that America watched together for nearly a year. The characters—gregarious Johnnie Cochran, doofy Kato Kaelin, circumspect Judge Ito—became household names. The dialogue—“If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit”—was indelible. It all inspired Saturday Night Live parodies, frequently distasteful merchandise, explosive watercooler conversations about race and domestic violence, and some pretty repulsive media tactics. But the daily airing of the trial was also many everyday Americans’ first exposure to the real criminal justice system, not the fictionalized version they’d watched on L.A. Law. The televised trial’s popularity proved to entertainment executives that there was a hunger for even the minutiae of courtroom drama, if the case was salacious enough. It’s a lesson they’ve taken to heart.

Created by Karina Longworth

Perhaps no crime has spawned more true-crime content than the hideous acts of Charles Manson and his “family.” But this season of You Must Remember This, Longworth’s long-running podcast exploring the less-told stories of 20th-century Hollywood, is the best thing out there on the subject. The key isn’t that Longworth uncovers new material or solves a mystery; it’s that she knows Hollywood and, with a critic’s eye for connecting the dots, elegantly intertwines Manson’s unquenchable desire for fame with the dramatic cultural shifts of the era, to show how late-’60s L.A. made Charles Manson possible. Longworth manages to convey the absolute horror of the Manson murders while also pointing out how ridiculous Manson himself was, and how the performative hedonism of Los Angeles at the time—which literally opened doors for Manson and his followers to wreak havoc from Sunset to Death Valley—is, looking back, almost embarrassing. Even Manson-philes will find something new in Longworth’s telling; she takes a familiar, famous story and weaves it into the fabric of place and time in a way that makes Manson’s evolution seem almost inevitable, rather than a horrific outlier to the cultural movements of the late ’60s.

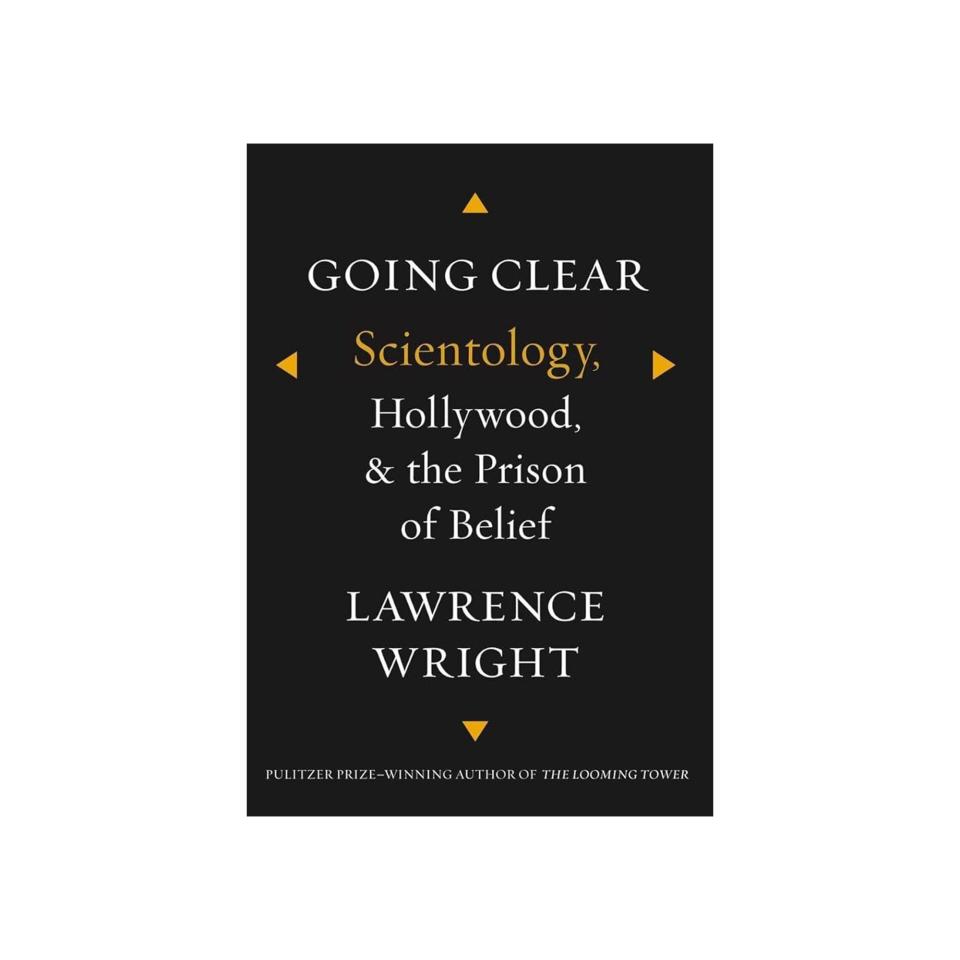

Written by Lawrence Wright

Cults belong to a gray area in the true-crime world. It can be difficult to pinpoint the criminality in persuading people to willingly ruin their own lives for the sake of a charismatic leader—it’s only in the aftermath, whether an extreme event like group suicide or simply a financial fleecing, that the crime becomes clear. Because of the secretive, isolationist nature of cults, though, there are seldom disinterested witnesses to their misdeeds. Pulitzer Prize winner Wright’s thoroughly fact-checked exposé, begun as a feature for the New Yorker, remains the definitive account of Scientology, from its origins as a scam concocted by the wily science-fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard through its unhinged efforts to steal unflattering records from government agencies to the many allegations of violent and abusive behavior leveled at the church’s current leader, David Miscavige. Wright pays particular attention to the church’s wooing of celebrity members, who are carefully shielded from its shadier activities and employed to lend an aura of legitimacy and glamor to an organization that otherwise has none. Given the church’s history of harassing its critics, the legal and personal risks Wright took on were considerable. Not all the dangers true-crime writers face come in the form of ruthless killers.

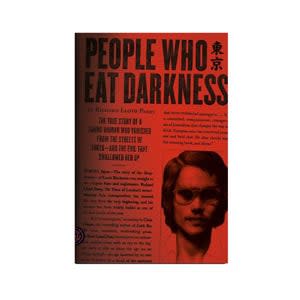

Written by Richard Lloyd Parry

Sometimes you can’t fully understand how a society’s rules work until they clash with the rules of another culture. Parry, a British foreign correspondent stationed in Tokyo, covered the 2000 disappearance of Lucie Blackman, a 21-year-old British former flight attendant working as a bar hostess in Japan. Embedded in the city and eventually becoming a trusted confidant of Blackman’s fractured family—who launched a high-profile campaign to pressure the inept Tokyo police department to find her—Parry knows this story deeply. In evocative prose, he shows how Japanese attitudes toward criminal justice, gender relations, and immigrants tangled with expat culture, and how the British tabloids imposed an expectation on family members to perform their fear and grief for the media in a way that bewildered the Japanese. At once the portrait of a single lost girl and a vivid picture of the world that made her and the world that consumed her, People Who Eat Darkness encounters only one mystery it can’t plumb: the strange cipher of the serial rapist responsible for Blackman’s death. Less a man than a void in human form, he haunts the Tokyo that Parry loves so well, the unknowable center of this unforgettable story.

Written by Patrick Radden Keefe

Ireland’s Troubles can feel impossible to fully grasp if you’re not someone who lived through them. The conflict was sprawling, but Say Nothing’s narrow focus on the disappearance of one young mother allows Keefe to weave the battle through the lives of real people on both sides. When citizens commit crimes under the aegis of war, Say Nothing asks, who is allowed to be forgiven? What does redemption even mean? At times a heart-pounding true-crime thriller, at others a devastating reflection on loss and the human price of rebellion, Say Nothing leads you through decades of violence without ever losing sight of the people affected the most. The best true crime serves as a lens through which to see the society it portrays; in Say Nothing, Keefe shines a light on one crime and illuminates a complex, intractable political and military dispute—while telling a deeper story of what war and political violence can do to the human psyche and heart.

Directed by Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn, and an anonymous Indonesian filmmaker

At once surreal and much too real, this celebrated documentary considers the cost of committing a crime that isn’t technically a crime. The filmmakers asked members of death squads hired by the Indonesian government in the 1960s to kill “Communists” (some of whom were merely members of the nation’s Chinese minority) to make a fictionalized film about their deeds. Gangsters rather than zealots, the men begin by cheerfully recounting the practical challenges in taking hundreds of lives. In one scene, a bubbly TV talk show host interviews them about the movie project, asking them their favorite film stars and whether they picked up any good execution tips from the movies. “Morality is relative,” one impervious minor character explains. “War crimes are defined by the winners. I’m a winner. So I get to make my own definition.” Then, cracks appear in the facade of one executioner, Anwar Congo, who confesses to having nightmares about his death squad days. In the scenes from the movie created by the killers, they perform all roles, and playing a victim further rumbles Congo’s conscience, to devastating effect. Intercut throughout are musical numbers from the executioners’ film featuring dancing girls emerging from a fish-shaped structure and one of the gangsters in spectacular drag—all adding to the sense of a fever dream that is really a nightmare in disguise. While this beautiful, disturbing, and enigmatic film may not be what most people think of when they think of “true crime,” what else would you call a work that so courageously addresses truth, justice, and the taking of human life?