17 New Books You Won’t Want to Miss This Fall

Thermometer be damned: Fall is coming! And with it, some of the publishing industry’s heftiest offerings. From big-ticket fiction to some charming posthumous releases, here’s a look at the best books to come in the next few months.

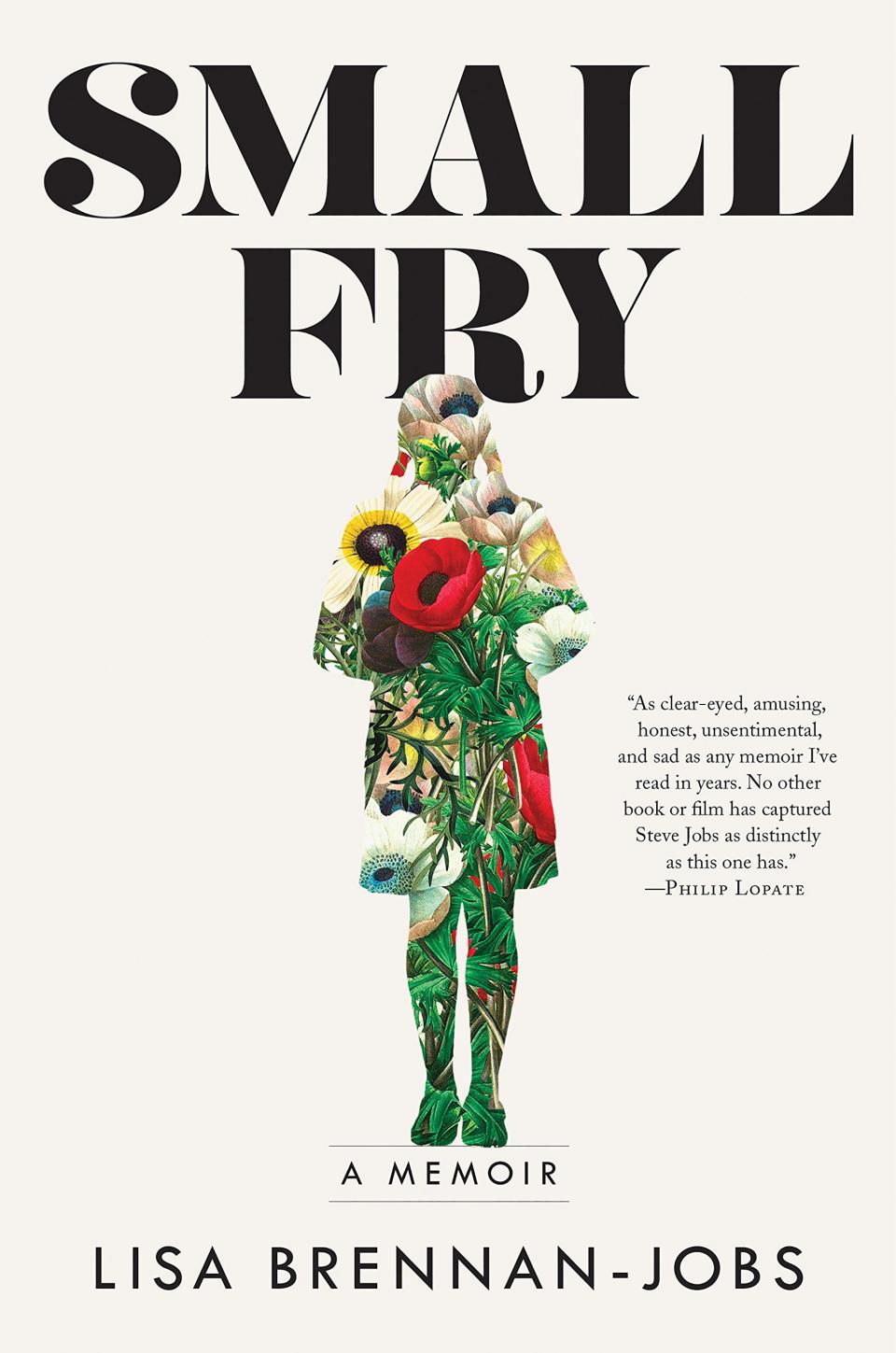

There are celebrities with command over our collective imagination, and then there is Steve Jobs. Seven years after his death, his legacy is probably in your pocket. With her artful memoir, Small Fry (Grove), his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, has written a book that upends expectations, delivering a masterly Silicon Valley gothic. Here is a chronicle of the spurned daughter who eventually moves into a half-furnished, under-heated Palo Alto mansion and duels not with ghosts but with her spookily withholding father. Brennan-Jobs’s intimate depiction of his capacity for cruelty is no less astonishing than her rendering of the scrappy underbelly of computer country. The bohemian landscape she captures will be virtually unrecognizable to anyone who equates this slice of Northern California with Teslas and tiger moms. Shortly before his death, Jobs apologized to Brennan-Jobs for his mistakes. “I owe you one,” he told her repeatedly during her visit. “I didn’t spend enough time with you when you were little.” But decades had accrued, and for Brennan-Jobs, the narrative had already assumed its shape. Of the book’s myriad achievements, the greatest might be making that story her own. —Lauren Mechling

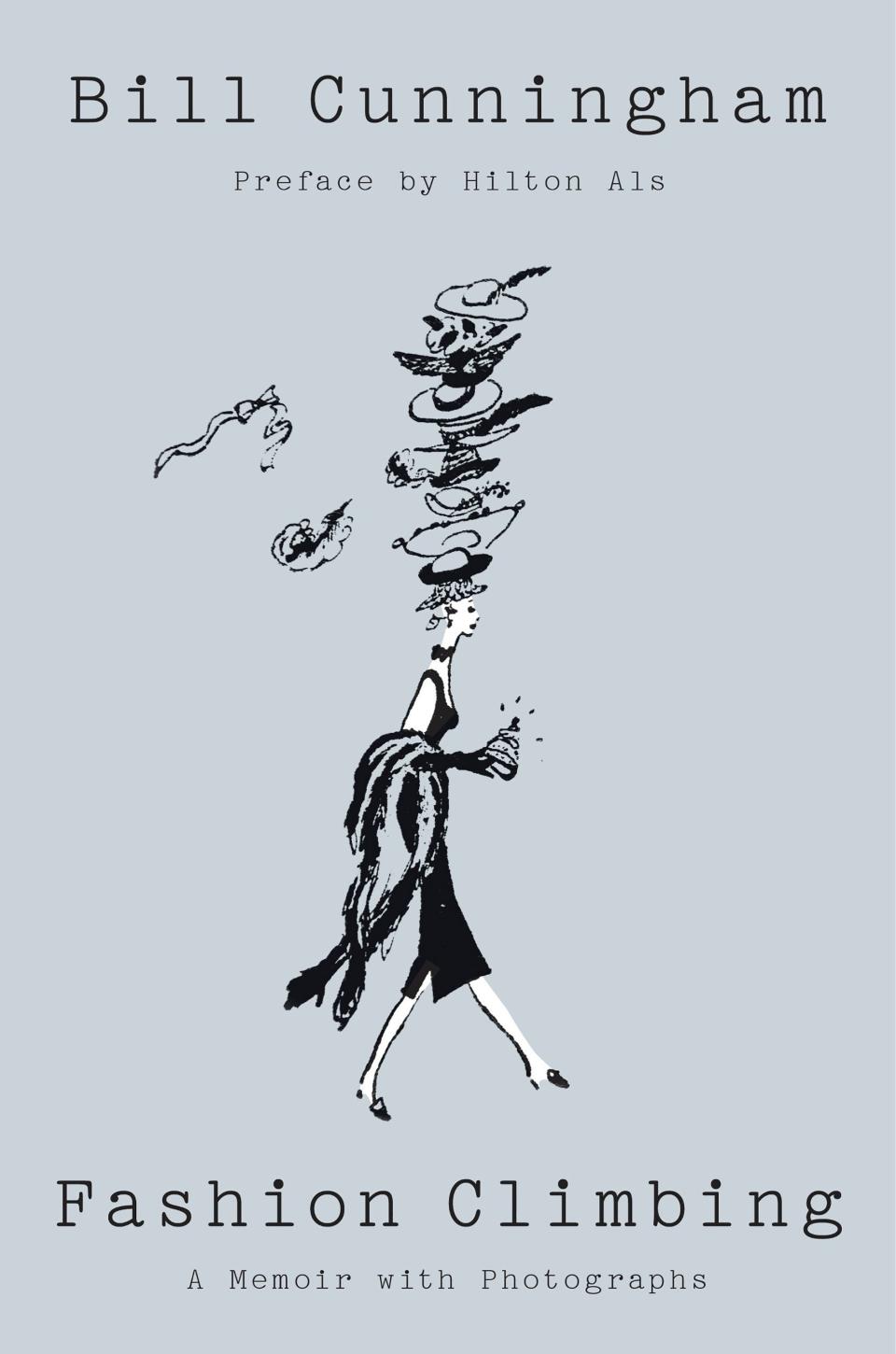

In March, The New York Times reported that the beloved bike-pedaling photographer Bill Cunningham had left behind a secret memoir. This fall, Penguin Press will publish Fashion Climbing, a chatty, personable account of Cunningham’s childhood, early years as a milliner, and ascent through the ranks. It’s a book that reads part diary, part manual of style. “Constant change is the breath of fashion,” writers Cunningham, but he will always be a classic. —Chloe Schama

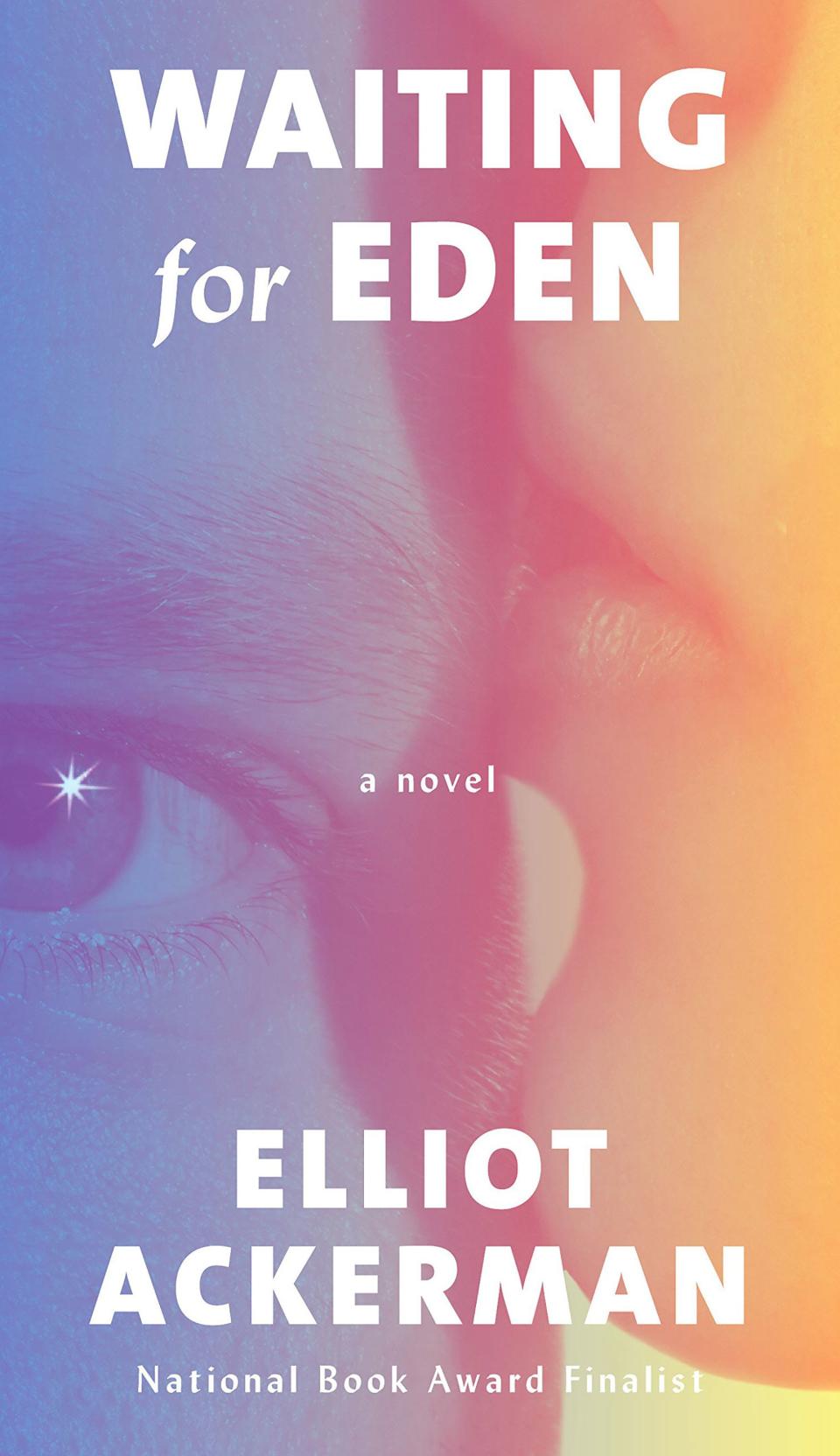

In his third novel, the former Marine turned novelist Elliot Ackerman further shows himself to be the Tim O’Brien of our era—an unflinching guide to the mental, physical, and familial toll of war. In his latest, and seemingly sparest, book, Ackerman tells the story of a gravely injured soldier and the wife who faithfully attends him. The book, as Ackerman puts it, is rooted not just in his own experience but in “the cumulative loss of many friends and the larger questions of how we keep faith with each other.” —C.S.

Framed as a “love letter to Kathy Acker”—the punk provocateur recently immortalized in a biography by Chris Kraus—Olivia Laing’s latest is also, like all her work, a blend between the heavily researched and the deeply personal. (She’s sort of like Rebecca Solnit, but less heady and more British.) Crudo is ostensibly a fictional story about a woman in her 40s who is marrying a much older man (ditto for Laing). The book was written in a short period over the course of the summer of 2017, so it also reads like a digest of those months. In short, it’s many things, and in the U.K., where it was published this summer, it’s been widely commended for it. —C.S.

I’m delighted to report that Deborah Eisenberg’s wonderfully strange short fiction has become even stranger. Your Duck Is My Duck is her new collection full of exquisitely rendered, off-kilter narratives. An artist in personal disarray accepts an invitation on a strangely savage holiday. A dissolute young man becomes obsessed with an aid worker. A girl in a clinic has her language denatured by a frightening doctor. The collection is as haunting as it is hilariously unsparing. —Taylor Antrim

Andre Dubus III has made a name for himself as a kind of poet of violence—a dubious accolade, to be sure—a writer who vibrantly captures a kind of hardscrabble New England living that’s not rough around the edges, it’s just rough. (Read his masterful and moving memoir, Townie, for a sense of where it all comes from.) His first novel in a decade, Gone So Long concerns a reckoning between an ex-convict who committed a violent and devastating crime, and his daughter who witnessed that crime as a young girl. —C.S.

Even if you only watched an episode or two of Dawson’s Creek (who are you?), you’ll be entertained by Busy Philipps’s dishy new memoir, which recounts everything from her start on Freaks and Geeks, to her move to North Carolina in order to film the teen TV classic, to weeks spent hanging out in Australia with a pregnant Michelle Williams. The book has a lot of all-caps emphasis that makes it feels like it leapt from one of Philipps’s super-popular Instagram Stories, but that doesn’t diminish its brash charms. —C.S.

Barbara Kingsolver’s latest was inspired, she says, by “a vague feeling that the world as we knew it was ending.” Everything from political rhetoric to the not-so-slow decimation of the environment confirmed her premonition. But, as she writes, the best way to understand a crisis is to step outside of it, in this case, into the 1870s, when Charles Darwin’s work was similarly upending expectations of the world as it was then known. Unsheltered tells the story of Mary Treat, a 19th-century scientist involved in the evolution debate, and it also tells the story of a current-day family, living in the town that Mary once occupied. These 21st-century denizens, Willa Knox and her husband, are reeling from a shifting economy and personal circumstances (their jobs and their pensions are gone; their unemployed, debt-ridden son has left them with a grandson to care for). A layered, ambitious work, the book will likely appeal to those who fell in love with Kingsolver 20 years ago when her masterpiece, The Poisonwood Bible, was published. —C.S.

This memoir, which reckons with sexuality, gender, and the institutional biases of Hollywood, would seem artificially engineered for the current cultural moment if it didn’t feel so naturally intimate and off the cuff. Written by the creator of Transparent, the last part of the book deals with the controversy surrounding Jeffrey Tambor’s behavior on set, and provides a firsthand, if slightly rushed, coda to the public story that unfolded earlier this year. —C.S.

Haruki Murakami’s novels have been increasing in heft in recent years, and some might say that they lack the restrained oddity of earlier works like Sputnik Sweetheart or Norwegian Wood. But the publication of a Murakami novel is still an event, and this one, a heavyweight on the scale of 2011’s 1Q84, is sure to be as well. Killing Commendatore begins with an enigmatic anecdote—an artist is called upon to sketch a portrait of a faceless man—and unfolds in the mysterious manner for which the Japanese novelist has earned international renown. —C.S.

If you felt Leonard Cohen’s death in 2016 as a personal assault, this book is a posthumous balm: a collection of previously unpublished poems, lyrics, and sketches. All of Cohen’s work has a raw, straight-to-the-heart intensity—reach for this the next time you need inspiration for a wedding toast that will leave them gutted, or any other moment you need a little sustenance for the soul. —C.S.

Tana French was an actress before the 2007 publication of her first book, In the Woods, and a strong sense of stagecraft runs through her work. The Vermont-born, Ireland-based novelist has made a name for herself with her addictive Dublin Murder Squad series, each of which centers on a different member of an investigative team. Readers love her for her hyper-specific setting—the crime-scene details are as vibrant as those outlining the boisterous pubs and idyllic Sunday family lunches—and intimate prose that goes down warm and easy. Her latest, The Witch Elm, is her first departure from the series, and here she focuses on the victim, not the detectives. Toby Hennessy is a handsome 28-year-old who works at a groovy art gallery and dates a woman with a “sunflower heart.” The clouds gather when a pair of burglars come calling and leave him for dead. He survives, though, with injuries that render him ill-equipped to withstand the head-spinning investigation that ensues when a human skeleton is found in the garden of his family home. French has spun an engrossing meditation on memory, identity, and family—a mystery novel in which the intrigue largely stems from its narrator’s impaired mental ability. A master of psychological complexity, she toys with the minds of her characters and readers both. —L.M.

Since her 1995 debut, Kate Atkinson has carved out a niche as a stylistic interloper, elevating seemingly grimy crime fiction with her mordant wit and skipping from family sagas to speculative fiction. She returns to radiant form with her latest, Transcription, a deceptively subversive spy novel set around World War II. The bulk of the story takes place in 1940, when the parentless 18-year-old Londoner Juliet Armstrong is recruited to work for an obscure department of MI5. Tasked with transcribing secret recordings of undercover agents and Fascist sympathizers, Juliet is handed a standing-room ticket to wartime intrigue—in which, as she learns, conversations about biscuits and pork chops figure as often as those about Gestapo funds and invisible ink. The narrative jumps between the war years and a decade later, when Juliet finds herself working for an educational BBC Radio program winkingly called Past Lives. One of the book’s foremost preoccupations is the human impulse to boil down complexity: Spycraft especially distills conflicts and crams people into tidy roles. But the borders cannot hold; Atkinson’s story sneakily builds to a revelation that blasts all that to bits. —L.M.

“Our contemporary neglect of our dream lives is not only a historical anomaly but a particular paradox in today’s culture,” writes journalist Alice Robb. We obsess over sleep, but we ignore its most liberating feature. In a book that looks at the historical and social importance of dreams, and analyzes the latest science, Robb attempts to correct our misguided forsaking of this feature of our unconscious. Dreams don’t make for boring conversation, Robb argues in this persuasive, personable book. —C.S.

Helen Schulman has a knack for social-realist novels that put their finger on the anxieties of the moment. (Her last just-a-beat-ahead-of-its-time work, This Beautiful Life, was about a sexting controversy at a private school; A Day at the Beach unfolded in the wake of a single day following September 11.) Her latest work circles around Amy, the middle-aged protagonist who has signed on to work for a Stanford dorm-room startup that’s poised to bring “multiverse theory”—an idea that taps into the idea of multiple versions of a life playing—to the mainstream (think Sliding Doors meets Silicon Valley). Schulman’s novel may be precisely located in the moment—weaving in details as precise as Amy’s Starbucks order and her creaking runner’s knees—but this is also a book about larger issues like technology and attachment. —C.S.

Though Liane Moriarty has been a mainstay of best-seller lists for years, the HBO adaptation of Big Little Lies elevated this Australian novelist to a higher plane. The first book since that critical phenomenon debuted, the film and TV rights for Nine Perfect Strangers have already been scooped up by Nicole Kidman. Set in a mindfulness retreat that may be more than its visitors bargained for, the novel promises to be an lively page-turner. —C.S.

Not a lot is known about the former First Lady’s memoir, but no fall preview would be complete without it. Becoming promises to tell the story of “growing up on Chicago’s South Side, working as an executive while raising kids, and of what it meant to be the first African-American First Lady,” according to Publisher’s Weekly. It seems safe to say that despite it’s low profile thus far, this one is highly anticipated. —C.S.

Read More Culture Stories:

Melania Trump Meets Vladimir Putin in Helsinki in Strange Video—Read More

How Pope Francis Is Changing the Catholic Church—Read More

Serena Williams’s Husband, Alexis Ohanian, Makes All the Other Husbands Look Bad—Read More

Lindsay Lohan’s New Reality TV Show: Is She Our Next Lisa Vanderpump?—Read More

Phone Addiction? Here’s One Way to Fix It—Read More