130 Years Later, 'The Adventures Of Sherlock Holmes' Is Still the Detective's Best Outing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

The popular conception of Sherlock Holmes varies depending on who you talk to. The most basic image is that he’s the guy who smokes a pipe and wields both a magnifying glass and his intellect to solve mysteries. He’s a mercurial brainiac, someone so smart that he coldly dismisses anyone who isn’t his mental equal. If you crack open what's arguably the most important Sherlock Holmes book of all time, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, all of those impressions appear in some form or another. But what these generalizations leave out is that Holmes has all sorts of other moods—including total hilarity. In “The Red-Headed League,” after he and Watson burst into laughter over some absurd details of a mystery, Holmes says to a client, “There is if you will excuse me saying so, something just a little funny about it.” Most Holmes short story titles are each preceded by the phrase “The Adventure of…,” and when you re-read The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, it makes sense. These are bonkers adventures first and complex mysteries second. 130 years later, it’s easy to see why this book is still so thrilling.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes was published in the United Kingdom on October 14, 1892, with a print run of 10,000 copies. On October 15, 1892, 4,500 copies of the American edition arrived. This was the third Sherlock Holmes book published overall, following the novels A Study In Scarlet (1887) and The Sign of the Four (1890). In total, there are only 60 total canonical Sherlock Holmes stories (not books) written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: four novels plus five collections, which together consist of 56 short stories. But in the fall of 1892, there were just those first two novels and the twelve stories that made up The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, all of which had been serialized in The Strand Magazine in the UK (and syndicated in American magazines and newspapers, too).

By the time The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes was published in 1892, another batch of 12 stories (later collected as The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes) was also appearing episodically in magazines, and public demand for Holmes was at an all-time high. It's tempting to compare the eventual publication of Adventures in book form to a Blu-ray boxed set of a TV season landing about a year after the episodes have aired on TV, concurrently with the airing of the next season. But that analogy only describes the logistics, not the impact.

Had The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes never been collected in one volume, it’s unlikely that the Holmes canon would have endured to the present day. Here’s why: the first two novels are simply not as exciting or amusing as the short stories. If you try to get a new reader into Sherlock Holmes by having them start with one of the novels (including the retroactive prequel The Hound of the Baskervilles), a contemporary reader will likely (and understandably) get bored. But not so with Adventures. While Doyle padded out his first two Holmes novels with historical and extended digressions into the backstories of the visiting characters, the stories in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes are lean and mean, full of captivating and memorable details. Part of the reason why is that these stories always contain at least three things happening at the same time: what’s going on with Holmes, what’s going on with Watson, and what’s going on with the guest characters in each adventure. In his 2008 essay, “Fan Fictions,” Michael Chabon points out that all the Holmes stories are actually “stories of people who tell their stories, and every so often, the stories these people tell feature people telling stories.” Because the narrator of the Sherlock Holmes adventures is not the main character, but instead Dr. Watson, this hall of mirrors helps to ground the stories in a game of telephone that scans as pseudo-realistic. Instead of the hero narrating his detective exploits, it's the gussied-up recollections of a part-time doctor who is also recalling the stories of others, through his very subjective viewpoint.

If you stop to consider all of these nested narratives, you’ve suddenly got all kinds of unreliable narrators—which is pretty hilarious, considering that Sherlock Holmes is known for discovering the empirical truth of all things. Make no mistake: this paradox is a feature, not a bug. The selective details by which Doyle has Watson weave his tales suggest another “real” truth lurking somewhere beneath these accounts. Watson isn’t just telling us the story for the sake of Doyle creating an artifice; these stories are also being published within Holmes and Watson’s fictional world. Holmes generally disapproves of these works of creative nonfiction and even suggests that Watson is lying to us, just a little bit. In The Sign of the Four, he decries, “you have attempted to tinge it [their adventure] with romanticism..” But then again, because Watson is the narrator, he is the one writing down the moment where Sherlock criticizes his writing. In any case, the reader is invited to think that there are, in fact, two versions of Holmes and Watson: the ones Watson has edited for the page, and the “real” ones dashing about out there in the Victorian gaslight.

This notion of dual identities crops up literally in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” “The Red-Headed League,” “A Case of Identity,” “The Man With the Twisted Lip,” and “The Copper Beeches.” In each of these stories—all included in The Adventures— an assumed identity or specific physical disguise is central to the mystery. Sherlock Holmes stories are not generally lauded for twists that involve masters of disguise, but let’s just say Scooby-Doo got that “pull the mask off” denouement from somewhere. In “The Man With the Twisted Lip,” (spoiler alert!) the mystery of a disappearing man is solved by Holmes using some soap and a sponge to wash a disguise off of another man, proving the missing person was just this other guy, all along. It sounds like a common twist, but Doyle did it first.

The revelation that truth is hiding in plain sight occurs over and over in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. As such, we feel that a more exciting and interesting world might be happening right now, right under our noses. Holmes himself puts it best in “The Red-Headed League” when he says: “As a rule… the more bizarre a thing is, the less mysterious it proves to be. It is your commonplace and featureless crimes which are really puzzling, just as a commonplace face is the most difficult to identify.” In the world of Sherlock Holmes, real life is the mystery and the adventure. In “A Case of Identity,” Holmes says to Watson, “Life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind of man could invent.”

And to that end, the best stories in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes generally don’t involve murder. Sherlock Holmes stories are often erroneously labeled as “whodunits,” but the real brilliance of a good chunk of Adventures is in how cool a mystery can be without murder. Both “The Red-Headed League” and “The Copper Beeches” involve weird jobs in which people are being mysteriously overpaid; one involves a strange haircut, while the other which is obsessed with hair. “The Blue Carbuncle” is about a missing gemstone that turns up in the most unlikely place. Even one of the best stories with murder—“The Speckled Band”—has such an outrageous twist that you hardly remember it was a murder case at all. In opposition to the grisly true crime-inspired mystery fiction of today, many Sherlock Holmes stories succeed as thrillers without resorting to the trope of introducing an evil psychopath.

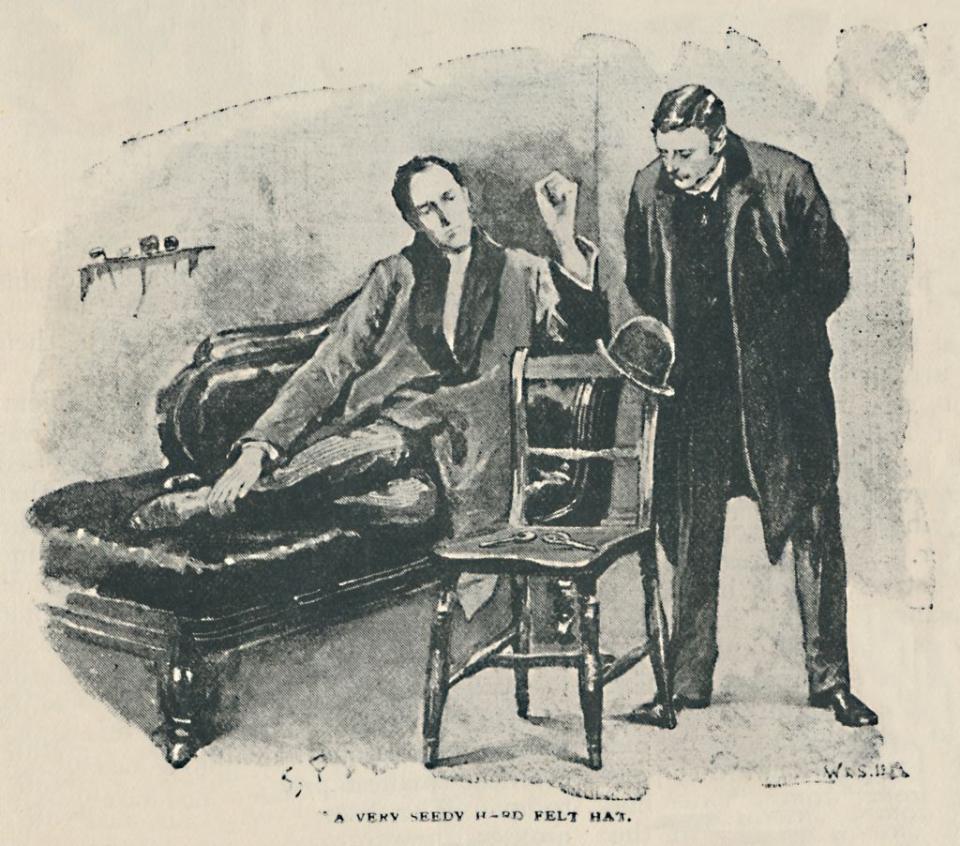

None of these ruminations would matter if the stories weren’t getting you to turn the pages. Yes, there are stories that begin with Holmes and Watson sitting around at 221B Baker Street, smoking and listening to people talk. But there are other stories that begin in motion. In “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” Watson barely has time to read a telegraph before he has to meet Holmes at the train station. And in “The Man With the Twisted Lip,” Watson stumbles upon Holmes deep undercover in an opium den while Watson is there bailing out a different friend in the midst of a lost weekend. (The misconception that Holmes is an opium addict probably comes from this story; however, Holmes’s canonical vices were shooting up morphine and a “seven percent solution” of cocaine.) But on top of all of this action, it’s also worth noting that very often, Holmes specifically does activities that are specifically not connected with his casework. In “The Red-Headed League,” in the middle of gathering clues, Holmes wants to take a break and invites Watson to the symphony to hear violin virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate play. Watson describes Holmes’s demeanor at the concert as utterly antithetical to “Holmes the sleuth hound” and asserts, “In his singular character the dual nature alternately asserted itself.”

In her wonderful book Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes, Maria Konnikova describes this as “distancing through an unrelated activity.” In addition to going to the symphony, in this story, Holmes also famously claims he needs to smoke three pipes to get to the bottom of the mystery. For Konnikova, Holmes doing stuff unrelated to his detective job is proof of his brilliance. As she writes in Mastermind: “When we switch gears, we in effect move the problem that we have been trying to solve from our conscious brain to our unconscious. While we may think we are doing something else—and indeed our attentional networks become engaged in something else—our brain doesn’t actually stop work on the original problem.”

Although hard-boiled detective novels or good spy novels also have their tangents, it’s hard to compete with the eccentric activities of Sherlock Holmes. In the very first story in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Watson tells us that “Holmes loathed every form of society with his whole Bohemian soul,” which makes the character both cranky as hell and a little punk rock, too. After the first novel, A Study in Scarlet, Doyle infused Holmes with more quirkiness, beginning with sprinkles of erratic behavior in The Sign of the Four, then perfecting him into a full-blown loveable madman in Adventures. As Robin Pogrebin and others have detailed, it was only after dinner with Oscar Wilde that Doyle was struck with the idea of making Holmes less of a Victorian gentleman and more of a savant. Doyle later described it as “indeed a golden evening for me.”

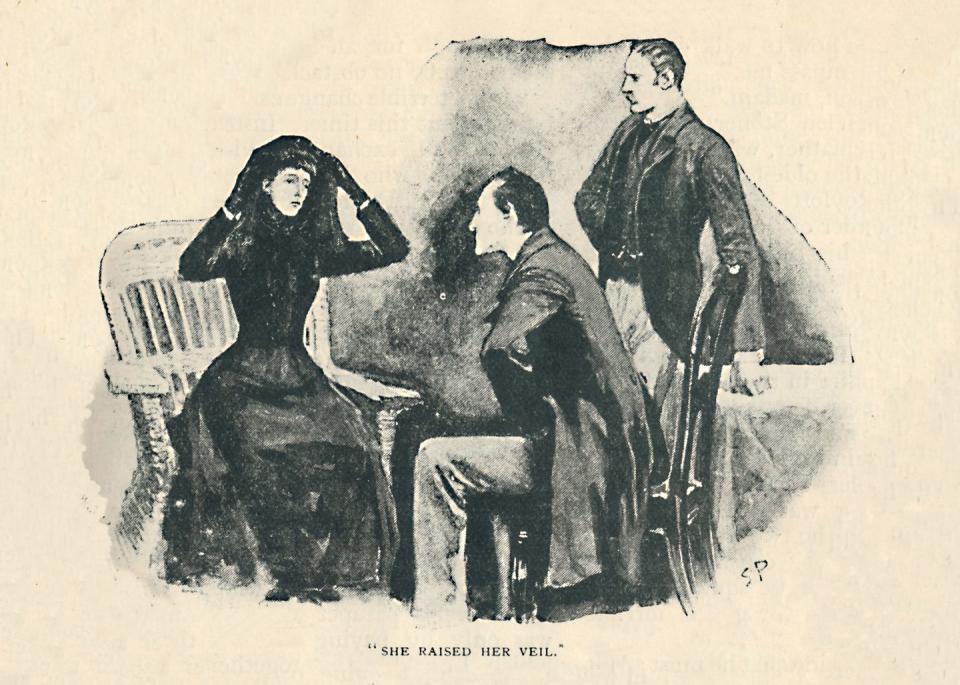

When you read “A Scandal in Bohemia,” the famous and much-loved story that opens The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, it’s tempting to see aspects of the story as a kind of Wilde tribute. In this story, there’s really no mystery to solve at all. Instead, Holmes is employed by “the King of Bohemia” to retrieve some compromising letters from the American opera singer and “adventuress” Irene Adler. The story then becomes a comedy of errors and a critique of social class. Holmes recognizes that Adler is weaponizing the letters for potential blackmail, only to wield power over the men that would destroy her. And because Holmes hates the trappings of social class, he, of course, falls in love with her. In the end, even though he’s employed to track down the letters, Holmes loses the case when he is outwitted by Adler. As Watson tells us, this outcome only contributes to Holmes’s affinity for her. When offered “an emerald snake ring,” as payment for his services as a detective, Holmes declines and only asks for the photograph of Irene Alder, which she left behind as a kind of taunt to him, letting the great detective know that she bested him. The story is more than a little funny, but also deeply romantic in a way that predicts the brilliance of Edith Wharton in The Age of Innocence. Holmes and Adler are alike, yet society and their occupations keep them apart.

Countless pieces of fanfiction, pastiche novels, and memorable TV and film adaptations have made much of the Adler-Holmes connection, but most stories in The Adventures are nothing like that singular story—the first Sherlock Holmes story many people will ever read. In a sense, Doyle gives us his very best and deepest story right away with “A Scandal in Bohemia.” And then, Doyle has Watson dial back the heat and focus on the everyday oddities instead. After all, Sherlock Holmes can’t fall in love every day. But, if you read—or re-read—The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, you’ll fall in love with Dr. Watson and Holmes himself, all over again.

You Might Also Like