How These 12 Boundary-Breaking Designers Continue to Think Globally

This September we’re taking you on a whirlwind—and impossibly stylish!—world tour. But don’t bother packing your passport. This odyssey is all thanks to the globally minded designers who simply refuse to see borders—fromKarl LagerfeldtoHedi Slimane, Stella McCartneytoJun Takahashi, Riccardo TiscitoDemna Gvasalia. Yet for all of this intrepid traveling, the final destination always remains the same: your closet. This fall, here’s what you’ll want to take along for the ride: one of the new coats, strong on design, rich in detail; the electric-bright “tech” colors, not traditionally autumnal but perfect for the year-round wardrobes of right now; and any one of the chic (and surprising) ways to go head first. The whole season, in fact, takes us to unexpected places. You might call it a trip.

Karl Lagerfeld

Karl Lagerfeld might be the original boundary-breaking fashion designer. Raised in bourgeois comfort in Hamburg, he set off for Paris and Pierre Balmain’s studio when he was a teenager and his work caught the attention of the couturier. Soon bored at Balmain, he left to become the head designer at the staid house of Jean Patou, but he was soon bored there, too, and, disillusioned with the world of the haute couture, left for Rome to study his favorite composer, Bellini. In 1965, however, he met the quintet of formidable Fendi sisters: By his own estimate, he has since traveled to Rome 800 times. In 1982, Alain Wertheimer hired Lagerfeld to revamp Chanel. “When I came to Chanel, I said to Mr. Wertheimer, ‘Let’s make a pact, like Faust with the Devil,’ ” Lagerfeld says. “But we don’t know who is the Devil and who is Faust.”

In 1992, when the supremely erudite Rosamond Bernier went to call on Lagerfeld, she noted that the designer owned seven houses in four countries, each furnished with museum-quality antiques, state-of-the-art contemporary commissions, and a quarter of a million books. Now he lives with his beloved cat, Choupette, surrounded by the tools of his work and food for his mind.

“I have so much to do that I’m not so much for traveling anymore,” Lagerfeld says. “For Chanel alone I do ten collections, and I do it all myself, all the sketches.” Those Chanel projects include showcasing the Métiers d’Art collections around the world, drawing attention to the skills of the great fashion fournisseurs that Chanel has acquired to ensure their survival—among them the embroidery house of Lesage, the feather-and-flower establishment of Lemarié, shoemakers Massaro, and milliner Maison Michel—and initiating the trend for exotic destination presentations. After forays to Mumbai, Salzburg, Dubai, Seoul, Havana, Singapore, and Linlithgow, in Scotland, Lagerfeld staged a triumphant homecoming in Hamburg last year.

Savagely unsentimental, relentlessly un-nostalgic, he remains, in his ninth decade, fueled by his insatiable curiosity and a passion for the present and the future. “I have a strong survival instinct,” he says. —Hamish Bowles

Marine Serre

It’s a broiling hot July day in Paris, and the electric fan valiantly whirring away to cool down Marine Serre’s studio has its work cut out for it. Yet Serre doesn’t seem unduly bothered. Her five-foot-nothing frame is clad in a billowing dress, and she’s sipping water from a tumbler not much bigger than a shot glass. But then, heat is something that she has had to get used to lately. While this 26-year old Marseilles native has only been in business for about a year, she now has fifteen employees, 70 retailers, one LVMH prize, and three collections to her name. “A year ago I was in school and couldn’t even pay for my apartment,” she says. “But I’m not scared, because I have nothing to lose.”

Serre’s audacious runway debut this past February upended clichéd notions of beauty and power by the way she slyly shot her looks through with political and sexual commentary: riotously patterned vintage scarves upcycled into dresses; sick, slick, fetish-y PVC coats; head-covering bodysuits dotted with her crescent-moon logo, a look equal parts high-performance athleticism and modest observance. Each of them was imbued with Serre’s exacting, fearless attitude—“One-meter-fifty, but a will of steel” is how Karl Lagerfeld once described her. “I think we need to be a little aggressive in a way, because things are so stuck,” she says. “If you keep doing things the same way, nothing will change.”

Those scarf dresses are a case in point. Serre had to work hard to persuade her factories to make them, given their technical complexities, and she relished the David and Goliath aspect of it. “The biggest challenge for a young designer now is learning to take care of yourself so you can be sharper,” she says, “because we have to be as quick as the big houses.” When she sold those dresses, though, she didn’t make a whole song and dance about the upcycling. “I don’t want to confuse Marine Serre with a brand that wants to make money doing green stuff,” she says. “Everyone should be caring about that already, because otherwise fashion is going to die anyway.”

It’s that stance—pragmatic in its progressiveness—that underscores Serre’s approach to everything she does. She’s of a generation that grew up with the world always at its fingertips thanks to technology. Social media’s periscope into far-flung destinations—not to mention her own peripatetic moves from Marseilles to Brussels and now Paris—has allowed her to honor cultural differences while celebrating what’s common to all of us. She recently took a work tour of Asia, and while she was struck by the rush of the new, it was the universality of life that captivated her. Likewise, Serre has been thrilled by how her moon leitmotif has traversed from continent to continent, each time interpreted—and appreciated—differently. “I think it’s quite symbolic with what is happening today,” she says. “There shouldn’t be boundaries when we’re making fashion.” —Mark Holgate

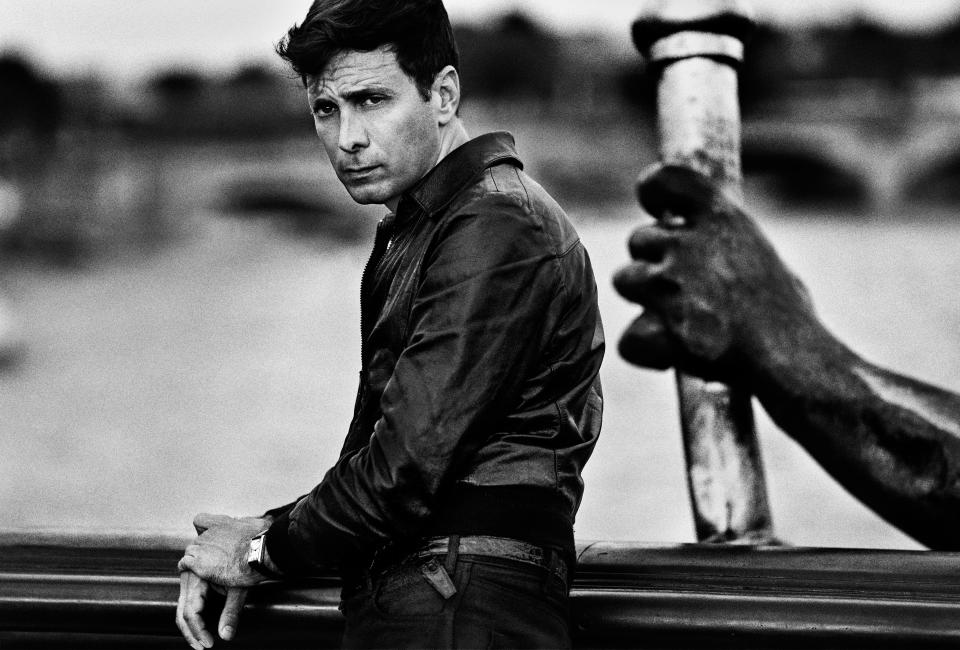

Riccardo Tisci

“It’s great to be back in London again!” says Riccardo Tisci as he takes up the reins at Burberry. “There’s been such an incredible evolution since I studied at Central Saint Martins nearly 20 years ago—I really feel the change. But one thing that always remains in this city is its diverse energy and incredible spirit. It’s what I loved so much as a student, and it’s something that’s so important in my work now at Burberry.”

Tisci could hardly be a better standard-bearer for the creative free flow of talent, ideas, and trade that is fashion’s modus operandi: an Italian, tutored in British-style individualism, who honed his couture skills in Paris at the top of a luxury house (Givenchy, which he helmed from 2005 to 2017) and is now chief creative officer of the biggest British brand of all. He fits no mold except his own. “I consider myself very nomadic,” Tisci says. “I have been so lucky and lived in so many places, making a big family of friends and relatives along the way.”

In a time when identity politics have become embedded in twenty-first-century consciousness, the fact that Tisci chose the image of a unicorn to accompany him for his Vogue portrait reverberates with resonances. Unicorns are symbols in both international pop culture and medieval British history—while a unicorn emoji might summon notions of a unique, wondrous, and sensitive person to a Gen Z–er, to a British person it immediately reads as the mythic beast on the lion-and-unicorn royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, a synonym for goodness and integrity that must be defended in the world. It was also—according to Tisci’s archival research—engraved on the Burberry family silver, presumably after the working-class owners had risen to wealth on the manufacture of check-lined trench coats.

Is this a picture meant to speak across generations? That would be totally Tisci—and not just because he has a long track record of ranging between haute couture and luxe streetwear. “Openness and breaking down borders have always been very important to me,” says the quiet revolutionary whose actions—in deeds, not words—made him a pioneer in dissolving the white, young, thin, heteronormative homogeneity of fashion and an opener of doors to every shade of gender and color in his time at Givenchy. “I am proud and very fortunate to have been able to champion progressive, strong, and forward-thinking people,” Tisci says with a shrug. “This has always felt instinctive for me, and it seems that it is becoming more and more natural and normal for the whole industry now, too.”

It’s a way of thinking, working, and living that fits right into the multicultural, LGBTQI-friendly ideals of the capital city, where Mayor Sadiq Khan’s #LondonIsOpen campaign has been waving a defiantly celebratory flag since the Brexit referendum in 2016. Tisci, of course, is one of thousands of Europeans contributing to the culture of modern British dynamism—albeit the one most visible in projecting it on the global stage. “It feels very natural for me to be bringing the house’s British heritage and style to people around the world,” he says. We will see just how he does it at his reveal during this month’s London Fashion Week. —Sarah Mower

Jun Takahashi

As a teenager growing up in a small town north of Tokyo in the early 1980s, Undercover founder Jun Takahashi was influenced mainly by British youth culture. At thirteen, he was listening to the Clash and the Sex Pistols. “I was shocked by the pink-and-yellow cover of Never Mind the Bollocks . . . ,” he recalls. “Visually shocked, and also shocked by their music, which was more aggressive than anything I had ever heard.” Though Takahashi went so far as to become the lead singer of a Sex Pistols cover band (“It was so bad,” he says, wincing), he was particularly drawn to the “idea or philosophy of punk—breaking the rules—but also to different types of cultures that had a twist. I was always attracted not just to the light but to the shadow.”

In 1989, at the age of 20, Takahashi became restless while studying at Tokyo’s prestigious Bunka Fashion College. “I wanted to make something original,” he says, “something unique or crazy that the school didn’t teach me.” He admired the clothes and accessories of iconoclastic British designers, including Christopher Nemeth, John Moore, and Judy Blame, which he saw in Tokyo’s Sector store. “They broke the traditional rules,” Takahashi says. “I wanted to mix all those different things— music, low and high fashion, and fashion connected to culture.” He founded Undercover by selling homemade graphic T-shirts to his friends, and soon made his first trip to London, where he befriended the visionary streetwear promoter Michael Kopelman.

Encouraged by Rei Kawakubo, Takahashi finally brought his holistic Undercover world to Paris in 2003, and he’s still riding the wave. After his recent forays into intricate Elizabethan couture and Cindy Sherman–inspired double-identity ensembles (fully reversible and presented on identical twins), Undercover’s spring 2019 womenswear collection is elevating staples of a teenage wardrobe, while his powerful men’s collection invented new tribes that blended elements from the movie The Warriors with autobiographical references to punk rock, the New Romantics, and eighties stylist Ray Petri’s Buffalo tribe. “I wanted to make different kinds of ‘tribal’—different kinds of clothes that show aspects of my creation through these imaginary groups and mixed races,” says Takahashi. “I can take cultures from outside, mix them, and create something out of it.” —Hamish Bowles

Demna Gvasalia

“This stars-and-stripes jacket, which represents the States, is my favorite—because American culture is what I loved when I was growing up.” The night before his Vetements show in July, Demna Gvasalia paused to pull out a patchworked-leather bomber, then turned it around and pointed to the slogan on the back. “What I like is that it says america, but in Russian.”

No one in the designer fashion world understands more about the human cost of what happens when neighbors fight over borders than Gvasalia, who was twelve years old when he and his younger brother (now his business partner) Guram had to flee their home during the brutal civil war that overtook Sukhumi, Georgia, in 1993. “Everybody today talks about war, refugees,” he says, “and I am like, yes—I know exactly what that means.” One of the dresses in the spring show was made from a single square of off-kiltered white cotton, a memory of the bedsheets the family grabbed as they fled to bomb shelters before eventually trekking across mountains under sniper fire. (Seen down the long barrel of history, Georgia’s problems then were only a dress rehearsal for the violent displacement of peoples across the Middle East, Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa, which are the continual horrors on our screens now.)

In his formative years, Gvasalia moved to Odessa (which is part of Ukraine but has recently been in conflict with Russia) and Düsseldorf, Germany, eventually studying fashion at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. Now he works in Paris—since 2015, as creative director of Balenciaga—and Zurich, where he chose to settle with the Vetements team last year.

Since he took up residence in clean, calm, safely neutral Switzerland—well away from any of fashion’s main drags—Gvasalia has increasingly channeled his past traumas into positive creative energy. National flags have been popping up in his work—in Balenciaga resort prints, on Vetements parkas—but on an equal footing with the international rainbow symbol for acceptance and love. A fake snowboarder’s mountain was installed as the set for the fall Balenciaga show, and on its crests and crevasses were multicolored graffiti—spray-painted, Gvasalia claimed, with words he and his team had been throwing around in the studio. Among the smiley faces and Balenciaga logos, two slogans jumped out: be aware and no borders. —Sarah Mower

Gosha Rubchinskiy

Moscow-born Gosha Rubchinskiy, 34, surprised the fashion world earlier this year by announcing the end—at least in its seasonal capacity—of his namesake line. His many ardent fans, though, needn’t worry—he’s got plenty in the pipeline: In July, Rubchinskiy opened a skate shop in Moscow, Oktyabr, named after a Russian skate team, and he’s further developing his skate line, Paccbet (pronounced rassviet—it means “sunrise” in Russian), launched with skateboarder Tolia Titaev.

Rubchinskiy made major waves with his label, founded in 2008 and later backed by Comme des Garçons, which delivered a singularly cool viewpoint of Russian youth culture to a global audience. His homeland-as-aesthetic muse—Cyrillic writing, tracksuits, clubwear influenced by late-Soviet-era underground parties—depicted Russia as a vibrant place with a community of people who share contemporary values and lifestyles (an especially welcome message given that, in the U.S. at least, recent Russia-related headlines told a rather different story). “I am happy that voices in Russia from the fashion and artistic world may be becoming more recognized elsewhere,” says the designer. “I don’t think any artist should be a spokesperson for a culture. I just want to express what I want to express—to be free.”

For his final three collections, Rubchinskiy staged runway shows in three different cities: Kaliningrad (where he unveiled a collaboration with Adidas in advance of this summer’s World Cup); St. Petersburg (where a collaboration with Burberry dropped); and Yekaterinburg. That last collection had the most interesting international touch of all: tops and scarves with the connected flags of the U.S., Russia, and Japan, all unveiled in the same place where the Kremlin’s nuclear briefcase from the Cold War is on display.

While the designer’s next big move is still under wraps, Rubchinskiy’s start-stop-start-again business model is true to a major trend of today’s fashion system, where niches are exploding and limited product drops rule the retail game. “If you aren’t thinking globally,” he says, “your thinking is out of date. The world is a small place.” —Nick Remsen

Johanna Ortiz

“When I tell people I’m from Cali, they think I mean California,” says designer Johanna Ortiz. Trace a line about three and a half thousand miles southeast of L.A. and you’ll land on Ortiz’s actual hometown in Colombia—a place that’s unofficially known as the salsa capital of the world. There’s no mistaking the tropical sway of her clothes, either: Hothouse flowers and foliage are recurring leitmotifs in her collections, and the tumbling ruffled asymmetric dresses that put her on the map seem primed for dancing, as do her new fringed Sevillian silk pieces. (At a recent dinner for the designer in New York, guests including Huma Abedin, Lauren Santo Domingo, and Alexa Chung were up on their feet twirling in the label’s swishy party looks to the sounds of a live salsa band before the main course had even been cleared from the table.)

Ortiz, 45, has been in business for fifteen years, growing from a team of two to a buzzing atelier of 380 employees, many of whom have been with her for ten years or more. (Helping to financially empower women in her local community is a big part of her mission.) She first gained an international audience for her self-titled line after partnering with Moda Operandi on an online trunk show in 2014, and since then, social media have helped to carry her name much farther afield: Her brand has been geotagged at just about every chic global hot spot you can imagine. “Every night I go onto Instagram to see all the women who have posted images in my clothes,” Ortiz says. “It’s so gratifying to see clothes designed and created in Cali go all around the world. It might be someone in the Middle East, China, or Europe—and they all wear it in their own way.” —Chioma Nnadi

Stella McCartney

Stella McCartney has always been a tree climber. Hers was an English-countryside childhood spent riding horses and shimmying up giant oaks. “I grew up being aware of the seasons and the planet’s power and immensity,” she says. And as McCartney learned more about the harm caused by fashion manufacturing, she began to approach all aspects of her burgeoning namesake line ethically. From its very beginnings in 2001, it has been leather-, fur-, and feather-free—a fearless and peerless stance in the early aughts, one motivated by her personal choices as a committed, lifelong vegetarian.

Climate change, of course, knows no borders. At some point, McCartney’s sustainable way of doing business will of necessity be the only way of doing business in a world of shrinking natural resources. But the designer, now 47, proved herself a pioneer all over again when she announced a collaboration with Bolt Threads, the Bay-area biotechnology company that engineers new fibers based on proteins found in nature—in this case, silk made from yeast rather than worms. Even more radical than laboratory-made silk: McCartney’s habit of telling her customers who come looking for sustainability advice to rent clothes or to buy vintage or secondhand (she’s partnered with the high-end resale site TheRealReal on a first-of-its-kind recommerce project).

Going against the grain, in fact, is precisely how McCartney has carved out her unique and—since buying the 50 percent share of her company that had been owned by the luxury giant Kering—newly independent space in the fashion sphere. “I know you can have a healthy business model in this industry that isn’t using leather, isn’t using PVCs, isn’t using fur; that tries to use solar panels or wind power in stores around the world. Working with and looking at technology gives me some hope,” she says. “How do you have children if you don’t have some kind of hope?”

McCartney has two boys and two girls—tree climbers, all of them—and she recently spoke to her younger daughter’s class. “I talked about fashion, and I tried to keep it exciting and glamorous—which it is. But then I started talking about the Loop shoe”—an in-house innovation that makes glue, which is typically made from animal or fish bones, unnecessary. Let’s just say she got their attention. “When you’re young, you have different expectations of how to treat our fellow creatures and how to respect the planet,” McCartney says. “It’s their future we’re talking about.” —Nicole Phelps

Hedi Slimane

In April 2016, Hedi Slimane revealed that, after a rollicking four- year tenure marked by his compulsive and convulsive rewriting of the house’s most revered codes, he was leaving Saint Laurent. Then, in January of this year, the news broke that Slimane was heading to Céline to replace the departed Phoebe Philo—another seismic jolt to the system, one amplified by the briefest of statements (Slimane has long been a man of few words but many actions) outlining that in addition to women’s collections there would also be, for the first time, a Céline collection for men, as well as haute couture in due course—or his version of it, at least.

Though these two events both occurred within 24 months, given the hyperspeed at which everything turns these days you might as well count the time elapsed in light-years. The political and cultural metamorphoses—and all that reordering of hierarchies and taste and beauty—that have touched us all have left Slimane eager to return to the fray. “Current evolutions make me want to focus, commit, and engage even more,” he says. “There is, besides, a really inspiring generation coming out.”

This is quintessential Slimane: a headlong rush into newness powered by the youthful energy fomenting in the world. “It’s quite liberating to see how new aesthetics can transcend preconceived ideas and conventions,” he adds. “It is important not to fall for generic or fake postures of progress, but rather to question a status quo, to have a clear and distinct voice.”

And what of Slimane’s voice, one of the most clear and distinctive out there: How has his time away altered its timbre? That initial an- nouncement aside, Slimane still has his finger pressed to his lips as to what, exactly, his Céline will look like, and so his debut show, to be held during the Paris spring 2019 collections, will deliver that rarest of things in fashion today: a genuine surprise. Yet it seems that he’s feeling the ground shift under his feet. For one thing, Los Angeles, whose sonic and aesthetic landscapes helped shape his vision for Saint Laurent, is being reevaluated.

“There is clearly a change, a certain edge that feels disturbing,” he says of his adopted hometown. “I’m always attached to the idea of California, but recently less so to the city of Los Angeles. I don’t feel comfortable with the evolution over the last few years—too many people have moved in; we have seen entire neighborhoods destroyed by speculation and developers. Something untouched, mysterious, and magical has gone.” Instead, this serial nomad, who has also lived in Berlin and London, is gazing back to France. “Clearly, the political shift has changed the dynamics of the city and the country in general,” Slimane says. “It has definitely moved my focus toward Paris.” —Mark Holgate

Virgil Abloh

“We’re in a time where this wash of humanity is truly influenc- ing—upstream—what fashion will become,” says Virgil Abloh. The indefatigable multitasker is the designer behind his own label, Off-White, as well as the new head of menswear at Louis Vuitton; a footwear collaborator with Nike; a furniture collaborator with Ikea; an artistic collaborator with Takashi Murakami; a formally trained architect; an in-demand DJ; and the subject of an upcoming exhibition about his own work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

Abloh, 38, is silhouetted by a citrine-yellow French summer sun on a recent Monday afternoon, relaxed and happy not long after the polychrome storm of his debut at Louis Vuitton, which featured a rainbow-painted catwalk meant to broadcast an international message of inclusivity and show notes with an infographic of the widespread birthplaces of his cast. Though his intention is nothing less than a reset of a company that’s been around since 1854, he’s kick-starting it with an entire world of inspiration—the exact opposite of a blank slate. And this is the thing about Abloh: He travels so extensively for his many jobs that there’s a kind of horizon-surpassing, border-blind eye to so much of what he creates.

Off-White, the label he founded independently, “gives me the freedom to chronicle what’s happening—and a large part of Off-White is the dialogue I’ve had between being from Rockford, Illinois, and spending time in Europe.” Those disparate settings are evinced in the vast range that Abloh builds into Off-White’s lineups: For fall, we see everything from a toile-printed corset (very modern French) to a gauzy ombré tulle dress (very modern Victoriana) to an all-black, action-hero-slick catsuit (very, well . . . modern American).

How, then, does someone who routinely spans the world with evidently limitless energy collect his thoughts to track, channel, and reflect the forever-transforming world? “It’s like I’m walking down different streets all at the same time, seeing, smelling, and breathing diversity, and realizing that things you grow up with—race, religion, gender, or anything else—tend to disappear once you’re embedded in a global community.”

As for what fuels Abloh’s engine, particularly when it comes to Off- White: “Young people in every city that I go to are loving life and actively participating in it. I am shocked at how open-minded young people of different cultures are compared to the presiding older generations. Australia, Tokyo, downtown Los Angeles: It’s the same community, bound by youth. And that gives me great hope.” —Nick Remsen

Domenico Dolce & Stefano Gabbana

Like Dolce & Gabbana’s jewelry show, their menswear show, their dinners, and their closing parties (the latest of which featured a performance from former One Direction star Liam Payne), the house’s recent four-day Alta Moda couture presentation was held in a procession of stupendously lovely villas alongside Lake Como. In tandem with the collection, created by a hundreds-strong in-house atelier, the location was designed to stimulate sensory shock and awe: total beauty overload.

No other event in fashion features such a globally diverse community (the audience for this one numbered around 300) mingling, making friends, and learning from one another. As Stefano Gabbana said after the show, “The clients come from across the world—every cor- ner—and they all have different eyes and sensibilities. That’s exciting.” While the best-represented regions were China, the U.S., Russia, and the Middle East, in that order, the net was cast far wider—to property tycoon Stephen Hung (Hong Kong) and his wife, Deborah (Mexico); conservationist Sylvia Mantella (Canada); entrepreneurs Serge and Cindy Pereira (Congo); politician JP Singh (India); and TV host Oksana Marchenko (Ukraine), not to mention scores of Brazilians, Spaniards, Britons, Angolans, Singaporeans, French, and more.

“Alta Moda is a vision of Italy—the best of Italy, seen through our eyes—made for the world to see,” said Domenico Dolce. The house has also been taking Alta Moda out and about—Beijing, New York, Tokyo, Mexico City, and London have all hosted capsule shows. “We listen to what our local clients and contacts want,” Dolce said. “And we respect these cultures. It’s very important not to be arrogant—we learn a lot from these trips.”

This Alta Moda–fired approach now informs the whole company’s ethos. Recent years have seen a heavy emphasis on courting millenni- als during ready-to-wear shows, which were cast with a global scope in mind, from Maluma (Colombia) to Natasha Lau (China), Luka Sabbat (U.S.), and Princess Olympia of Greece.

Is this internationalist ethos born of market research? “No!” said Gabbana urgently. “We do what we do out of instinct. You can’t ex- pect the world to be interested in what you are doing unless you are interested in what the world is doing. If you want to be listened to, then pay attention. You’ll probably learn something you never knew before.” —Luke Leitch

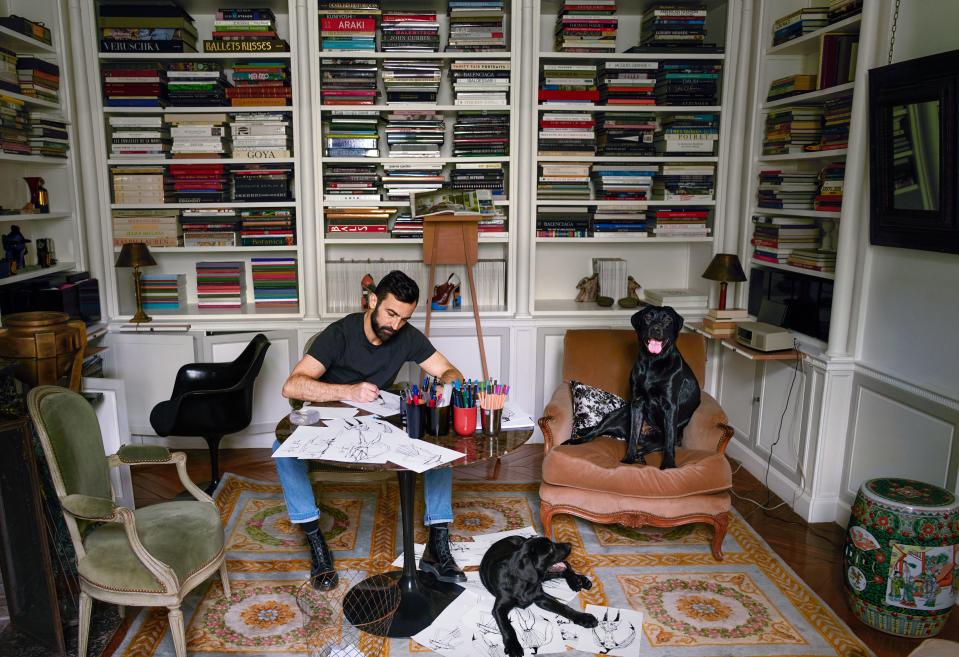

Nicolas Ghesquière

In late May of this year, Nicolas Ghesquière took to Instagram, where he announced to his nearly 700,000 followers: “Happy to renew my commitment with the beautiful house of @louisvuitton.” A week later, he presented his cruise collection for 2019 at the Fondation Maeght in the south of France. Inspired by the eccentricity of the museum’s founders, Marguerite and Aimé Maeght, it was his loosest, most spirited offering to date for the label, an eclectic mash-up of sharp tailoring played against soft dresses, delicate peignoirs and ruffled bloomers, hand-painted denim, techno–sneaker boots, and collectible bags made in collaboration with Vogue’s Grace Coddington. Reflecting on his decision a month later, Ghesquière said, “We’re opening another chapter of our story, and the trust we built in the years together is helping me to explore new things—it’s a great feeling.” Bucking the industry trend that is seeing designers come and go from prestigious labels with increasing speed, arguably weakening both the brands and the designers in the process, Ghesquière revealed that he had renewed a multiyear contract with LV.

Louis Vuitton is the most international of brands: Established in 1854 as a malletier, or trunk-maker, it has travel at its very heart—a point Ghesquière continues to make with his round-the-world resort collections. Before Saint-Paul-de-Vence’s Fondation Maeght, it was I. M. Pei’s Miho Museum in the forest outside Kyoto, and before that the Niterói in Rio de Janeiro. At each port of call, nearly half the audience consists of clients, many of whom travel from distant countries. But if the label is global, it has not always been inclusive. “Vuitton is a very big boat; it’s quite traditional, and it has to be protected—the craft, the savoir faire,” says Ghesquière. “I think some people don’t cross the door of a Louis Vuitton store because it’s too intimidating or because they think there’s not enough experimentation. But I’m here to shake—to break—the boundaries.” Ghesquière promises that his next five years will bring more experimentation and a greater sense of inclusivity. “We’re all concerned about diversity—more than just in fashion shows. In terms of actions and associations and organizations around the world, Louis Vuitton can do more.”

It’s fair to say the designer has been doing a good bit of self-exploration lately. He’s establishing his archives in Paris, and he’s hired an assistant to begin collecting pieces, both digitally and physically. “I think it’s time for me to have a very nice place where my work will be reunited,” he says. “It’s not that I want to be nostalgic, but it’s always great to look back and see your fundamentals. It’s probably where I’ll find my future.” *—Nicole Phelps

In this story:

Fashion Editors: Tabitha Simmons and Phyllis Posnick.