11 Climbers Who Shouldn’t Have Survived

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Climbing

BARRY BLANCHARD, MARK TWIGHT, KEVIN DOYLE AND WARD ROBINSON >> In 1988, Blanchard, Twight, Doyle and Robinson attempted an alpine-style ascent of the 15,000-foot Rupal Face on Nanga Parbat. During the climbers' harrowing descent, Doyle and Blanchard dropped their two ropes. After downclimbing 1,000 feet, the four happened to find a stuff sack containing two ropes, 20 pitons, food and fuel, all left by a Japanese expedition three years before. The four Japanese climbers had disappeared.

Recalls Blanchard, "We needed that equipment desperately, and used it for the purpose it had been left for. We all walked away carrying a trace of a Japanese soul."

He adds with humor, "The ropes, perfectly preserved in ice, were even the right brand for our sponsorship."

LYNN HILL >> In 1989, the world champion Lynn Hill had threaded her harness preparatory to climbing the classic warm-up route Buffet Froid (5.11a) at Buoux, France, when she walked 20 feet away for her climbing shoes. Wearing a bulky jacket, she never saw that she had not completed her double bowline, nor did the gentle but steady tug of a toprope pull the rope out of her harness during the 70-foot climb. At the anchors, she leaned out to lower--and the rope popped free. Hill plunged. Circling her arms in the air to stay upright, she instinctively looked for a landing and spotted a small oak tree left of the route.

"I followed my instinct to roll slightly left," says Hill, "tucking my body into a ball just before impact." She whipped through the branches to land, with what a witness described as a three-foot bounce, on the exposed tree roots. She escaped with a cut in the chest and a dislocated elbow.

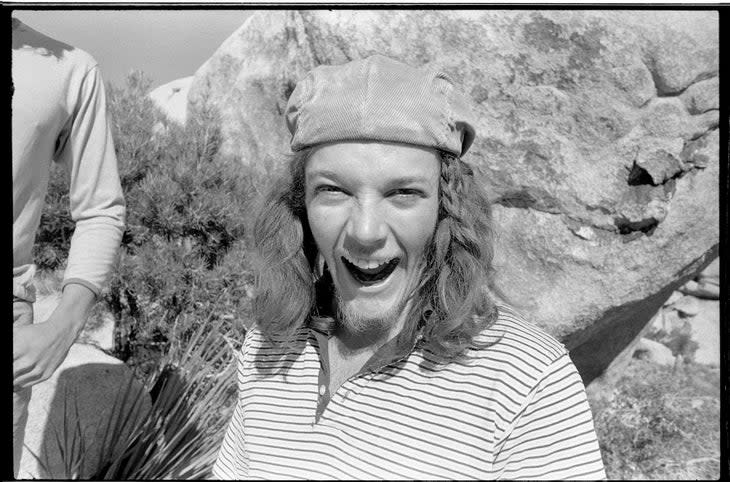

JOHN YABLONSKi >> Oh, Yabo. He may be no longer with us, but of course he was the king of luck, with more sketchy solos than anybody: More Monkey Than Funky (5.11c), Spider Line (5.11+) and Leave it to Beaver (5.12a), all at Joshua Tree.

John Bachar watched him on More Monkey Than Funky: "Over the lip," he recalls in vivid present tense, "he has two thumb-down hand jams ... It's thin hands, and he butters out of both jams, gastoning the side of the crack ... He was whimpering, totally losing it, crying and shit like that ... He starts pumping his body into the rock like he's gonna throw, catches a flaring jam right at the last millimeter, then gives out a little laugh. He went from pure nightmare to laughing in the space of a second."

Another time, Yabo fell off the last move, at 25 or 30 feet, of Short Circuit (5.11d) in Yosemite, and landed in a bay tree that bent and gently deposited him, on his feet, at its base.

Seeking, with Mike Lechlinski, a one-day ascent of the Triple Direct (VI 5.9 C2) on El Cap, Yablonski had run it out 80 feet, at 4 a.m., when he pitched. About to fall 160 feet, he stopped halfway when his rope hooked over an accommodating protrusion. Lechlinski lowered him. When he flipped the rope, it tumbled down.

Randy Leavitt, then perched high above in a portaledge, recalls, "I heard Yabo's bloodcurdling screams as he headed for his certain death. Nothing after."

MALCOLM DALY >> When Daly fell 150 feet off the last technical move of a route on the 10,920-foot Thunder Mountain, above the Tokositna Glacier in Alaska, with Jim Donini in May 1999, he broke his tib-fib on one leg and turned the talus on the other foot into powder, but lived. Though his rope was nearly chopped through, it held. Donini, though harpooned in the leg by Daly's crampon, downclimbed alone, in five hours, for help. Daly was rescued by helicopter after 46 hours on a ledge, during a brief break in the weather, which then closed in for a week. Still, the best bits of luck of all boil down to these: that, only five minutes after Donini reached the flats and the pair's tent, pilot and friend Paul Roderick of Talkeetna Air Taxi flew by on a notion to check on them, even though he already had done so that day. Donini had also only just moved out of shadow, and owned a bright-orange Patagonia suit that he waved madly around. "That's what Paul saw," he says, "and he knew something was wrong."

Today Daly, who lost one foot to frostbite, remains an extremely upbeat and active amputee climber.

JIM McCARTHY >> In the 1950s, Jim Mc Carthy, then a Shawangunks regular, later president of the American Alpine Club, was climbing with Dave Craft and George Bloom when he led up the easy first pitch of Bishop's Terrace (5.8) in Yosemite Valley. He went up a corner and across to the belay ledge at 90 feet, placing no pro, but then decided to go back and protect the traverse. Descending, he wrapped his hands around a "handy" crack set back about eight inches into the stance. Suddenly, the crack opened and half the ledge--a chunk of hundreds of pounds--sheared. He rocketed downward.

Just as he hit the ground, which fortunately sloped at the base, the rope, a Goldline, came tight. It had caught behind "a really small flake," the size of an ordinary book, at the beginning of the traverse. "How in hell it ever held," Mc Carthy says, "I'll never know." He limped away with a sprained ankle.

RUSS CLUNE >> In 1990, due to miscommunication with a longtime partner who thought Clune was rappelling and took him off belay, Clune was dropped 35 to 40 feet off the Survival Block (thus cementing its name for evermore), in the Shawangunks, onto jagged talus. Astonishingly, he stuck the landing ("A perfect 10!" he says), staying upright. More amazing was that he sustained only a broken heel.

Also present that day were Mark and Susan Robinson, both physicians.

"If you're gonna fall 35 or 40 feet onto talus," Clune says, "you might as well do it with an orthopedic surgeon and an internist [present]."

PETER MAYFIELD >> The first pitch of the two-pitch classic Reeds' Direct (5.10a) in Yosemite is an arching crack, a 5.9 layback about 40 feet long, looming above a ledge reached by a steep scramble of about the same length.

In 1983, Peter Mayfield, then 20 and a new guide, led the pitch for a client without placing any pro. When he reached the belay ledge, the rope, normally held in the outer region of the crack by protection, was stuck below. He began walking back over the ledge to downclimb and "unstick" it. Suddenly, in a "classic vertigo moment," he lost his balance.

"At first, the rope seemed like it was sliding through," he recalls. But then it jammed--farther down the rope, he thinks, than the original snag. Later, he would find 12 feet of sheath missing.

"I fell 40 feet and hit the little ledge, and just broke my heel, but I was expecting to go all the way"--80 feet.

"There's a classic moral to the story," Mayfield adds. "I had stayed up all night. I shouldn't have been guiding, or climbing at all. I was transitioning from being a 'hot climber' into a guide. Sometimes I was still getting my thrills even when guiding. What I learned from that was to protect things. And get my kicks on my days off."

CORAL BOWMAN >> In 1979, six years after Jim Erickson and Duncan Ferguson freed the Naked Edge (5.11a) in Eldorado Springs Canyon, Colorado, Bowman and Sue Giller hoped to become the first women's team up the famed testpiece. Giller was leading the third pitch when the pair's haul line snagged. She downclimbed, and Bowman, irked at the delay, hurriedly set up a rappel with their 11mm lead line. She intended to rap, free the snag and climb back up on toprope with a belay on the lead cord. She clipped in, descended a few feet and, at a small roof, leaned back. A metal click sounded, and then she dropped, her rope with her. The rope had unclipped across the gates of her two anchor carabiners, which she had not reversed. The two women's eyes met for a flash, as they thought: 'She's dead' / 'I'm dead.' Twenty feet down, Bowman seized the thin haul line. At first she appeared not to slow, but after 50 feet, burning furrows into her hands, she stopped. She swung into a belay ledge and clipped in. The fall, which she would term a "wake-up call," ended her climbing, but some felt that at the time she was the best woman climber in the world.

This article first appeared in Rock and Ice, June 2005.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.]]>