100 Women of Color Remember Their First Encounter With Racism—And How They Overcame It

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.

This was a mantra I picked up on the playground at elementary school—something I repeated over and over again anytime I came face to face with racism. It was a coping mechanism meant to guard my heart from the cacophony of discriminatory comments that shaped me as a young Korean American girl growing up in predominantly white spaces. But now that I’m well into adulthood, I think about the girls of color who are also being taught to pretend that words don’t hurt—and the people this way of thinking actually protects.

It’s hard to escape the unrelenting consequences of racism: In the past year alone, we lost Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and the six women of Asian descent murdered in Atlanta (Xiaojie “Emily” Tan, Daoyou Feng, Suncha Kim, Yong Ae Yue, Soon Chung Park, Hyun Jung Grant) at the hands of this insidious disease—and those are just the names that were in the headlines. If we don’t acknowledge the power words can carry and let racism hover over everything from our dinner tables to our children’s schoolyards, future generations of color will continue to bear the burden of witnessing race-based violence.

Racial discrimination can take root at an early age. According to Dr. Tami Benton, the Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania, “Children as early as 3 months old start to prefer faces that look like their mother. By the time kids are two, they start selecting playmates that look like them. They begin to recognize sameness and make decisions about situations based on the experience of race.” Benton also notes how quickly adolescents can “internalize negativity about themselves which can shape their development for many, many years to come.”

We also know that, both emotionally and physically, words can hurt you—especially racist ones. “There is data that suggests that stress associated with experiencing racism actually causes people to be physically ill,” notes Benton. “That’s very real and that’s at every stage—for young people and adults. But traumatic experiences don’t have to reside with us all the time if there’s an opportunity to talk to someone who can help us process.

To encourage this conversation, Oprah Daily is sharing the stories of 100 women of color who experienced racism at a young age—and are still feeling the impact today.

As Dr. Maya Angelou once put it: “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Read Stories From...

Athletes | Activists, Advocates, Politicians | Artists, Creatives, Entertainers | Writers and Journalists | Scientists and Doctors | Educators and Community Leaders | Businesswomen and Entrepreneurs

Athletes

WNBA player

“I was at my older brother's high school game when I was about 6, and a little boy behind the bleachers called me the n-word. My parents would have conversations with me about the word, and I thought it was just something they were preparing me for, but when it happened, it was just...shock. After, he ran off. I tried to find him, because I knew it was wrong.

That experience alone changed how comfortable I am with being different, and how comfortable I am with saying things aren't right. I think in order for things to change, you kind of have to be comfortable being different, because somebody's got to walk into the room and be the only one. Somebody had to make room for somebody else at the table. There's so many people that have done it before me, and have made me feel more comfortable. But there's still so much more to do."

Olympic medalist; sabre fencer

"As someone who lives at the intersection of my ethnic and religious identity, I never really know where the discrimination stems from. In those moments, I don't stop and ask someone: ‘Hey, quick question. You're being really mean, but I'm just wondering if it's because of my hijab or because of my race?’

I remember in fencing competitions other coaches would ask to see proof I was wearing a head covering for religious reasons. It would only happen at big competitions, right before we were due to start the match. As an adult, I realize it was an effort to throw off my mental game because they couldn't hang with me athletically on the fencing strip. To see that kind of racial residue still exist in sports is tough, but what always gets me up in the morning and encourages me to train harder, is knowing that the work I put in makes it easier for the kids who come after me. Not just because they can see themselves, but also because you've shown coaches, spectators, other athletes that we, too, can be successful in sports."

Olympic gold medalist; water polo player

“My sister and I were about 12 and playing a water polo game. We won, and we were shaking hands with the people that we played against. Everyone said, ‘Good game’ except this one boy, who said: ‘Black game, Black game.’ We didn't really understand what he was saying, but it felt disrespectful. At that age, I knew it was racist, but what I didn't know was how to stand up for myself in that moment. Now, I fully appreciate what it means to be Black, and to stand up and be a role model for other people who look like me. That's something really special about my purpose in this sport. It's really important to me to share these kinds of stories for young Black girls and Black boys in my sport, because I know that people experience that type of thing and way worse every day.”

Professional wrestler

“I was around 9 years old. I had moved to Iowa from California—my mom’s from Iowa—and I was the only person of color in the town. I remember walking to my auntie’s house from baseball practice and this old guy on the porch said: ‘What are you doing here n****r?' In California, I heard people say the n-word in a friendly way, so I never thought that word was anything bad until this man said it to me in such an angry, aggressive tone that really scared me. I was so shaken by that, and it’s probably one of my earliest memories. But that man saying that to me pushed me to be more. Any person that was mean to me only drove me to be the best so I could prove to them that I’m more than their words."

Dancer

“It was Halloween. One of my close friends at the time was white, and she invited me to her grandma’s place to go trick-or-treating. I remember coming back to her grandma’s house, and she cooked soup for us. My friend took me into the kitchen and told me to pour my soup out. I asked her why, and she said it was because her grandma put something in my soup to make me sick. I also overheard her grandma saying to her mom, ‘I told you I didn’t want you to bring people like that over to my house.’ I knew I looked different from them, but I didn’t realize it was a problem until things like that started happening. I was confused, because all I had experienced in my household was love and joy. Self-love is probably one of the best lessons you can teach a kid. When you learn to love yourself at such a young age, other people’s opinions don’t shake your world.”

Principal dancer, American Ballet Theatre

“I was 15 years old and ecstatic when I was invited to leave my home state of California to dance the lead in a ballet as a guest artist with another school. I learned all of the choreography and was prepared months in advance. When I arrived, I was told to act as if I didn’t know the choreography, because in reality, I was auditioning for the lead with the local dancers. I was confused as to why I got on a flight and rehearsed for months, only to be auditioning for the role.

I ended up performing as the lead, but was so conflicted inside. Years later, I learned that my teacher brought me because I was the best person for the role, but she had to show the director and teachers of the school that a Black girl was capable. So we pretended I was always meant to come and audition. He kept this from me so that I wouldn’t feel discouraged and would dance to my best ability. I was used to feeling different even before ballet; I was biracial, introverted, and extremely poor. Looking back, I realize how little has changed from that time until now. I always believed that if I just showed the ballet community what I could do, my skin color eventually wouldn’t matter. But this wasn’t always true, and still isn’t. The experience, and so many after that, made me feel a sense of responsibility to represent Black and brown people.”

Activists, Advocates, Politicians

Founder, Girls Who Code

“I grew up in Illinois in the 1980s. My parents came here as refugees from Uganda, though originally, they're from India. We were living in a place that was pretty white, and it was hard. When I was in eighth grade, I just wanted to fit in. I was angry that my parents named me Reshma instead of Rachel, and I didn't embrace my ethnic identity at all. The last day of eighth grade, this group of girls called me a ‘hadji’—a derogatory word they would call the brown kids.

I had enough and decided to fight back. We agreed to meet at the end of the day in the schoolyard for a fistfight. It was an opportunity for me to stop hiding and stand up for myself. At the end of the day, I showed up at the designated spot behind the school. Almost every single person in the eighth grade was standing there, and before I could even put my backpack down, all I saw was all these girls coming at me, and knuckles in my face. I blacked out almost immediately. I decided after that fight that I wasn't going to try to be white anymore. I was brown, I was a desi, I was an Indian girl whose name was Reshma, and I was going to embrace it. That really started off who I am today, always fighting for diversity and racial equity with Girls who Code classrooms.”

Minister; activist; CEO of The King Center

“I was predominantly protected as a kid. My first real encounter with racism was in law school. I had a professor who would single me and this other Black student out; we were the only two in the class. He would give me a lot of trouble, so I decided one day to write him a long letter explaining the difficulty of being Black in an all-white environment, feeling as if you are carrying the weight of the entire Black community. He had the nerve to write me back to say ‘If African Americans would try harder...’ implying that we were lazy. Oh, my God, that set me off.

It was so detrimental to me that only 2 or 3 weeks from the end of the semester, I dropped out of all my classes, because I was devastated by the things he wrote in his letter. When I went to confront him about it he just reiterated those things loudly—in front of his secretary who was African American.

With my father (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.) being assassinated when I was five, and then my uncle being mysteriously found in his pool, my grandmother being shot at church when I was 11...I was carrying a lot of bitterness and even rage. It took me 12 years to get through it. So we have to really guard our hearts when we're dealing with these kind of situations. Because there’s no telling what I could have accomplished or experienced had those feelings not gotten in the way.”

Activist

“The first time I knew people didn’t like me because I was a Black girl, was in Catholic school. I learned quickly that there was a difference in the way I was treated because of how I looked. Although the individuals perpetuating the behavior were white, the divisiveness was actually caused between Black and brown students. The girls who were of Latino descent with curly hair and lighter skin were treated better than darker skin girls like myself. We were punished more severely. It became very evident to me and many of the other dark skin Black girls that there was favoritism being shown to the other kids.

I think those experiences helped me to define my activism. Colorism for me has always been a concern and whenever I see that people I come into contact with are not being treated properly because of their skin tone, I try my best to give those people platforms and call out those who are participating in the harm.”

Labor activist

“Where do I begin? I hated preschool because my teachers couldn’t say my name, and the other kids would tease me with this horrible chant: ‘Chinese, Japanese, Dirtynese, look at these.’ I remember feeling like I would never be accepted. I even tried to convince my parents to let me change my name to Lisa. Now, I’m so glad they didn’t let me do that. Since then, I’ve spent 20 years working with people who’ve been undervalued for their incredible contributions as essential workers. It probably is connected to the fact that on some deep level, I can relate to the harm that happens when someone’s humanity and sense of belonging is not affirmed. I think it’s up to us to both imagine and create a world where that doesn’t happen anymore.”

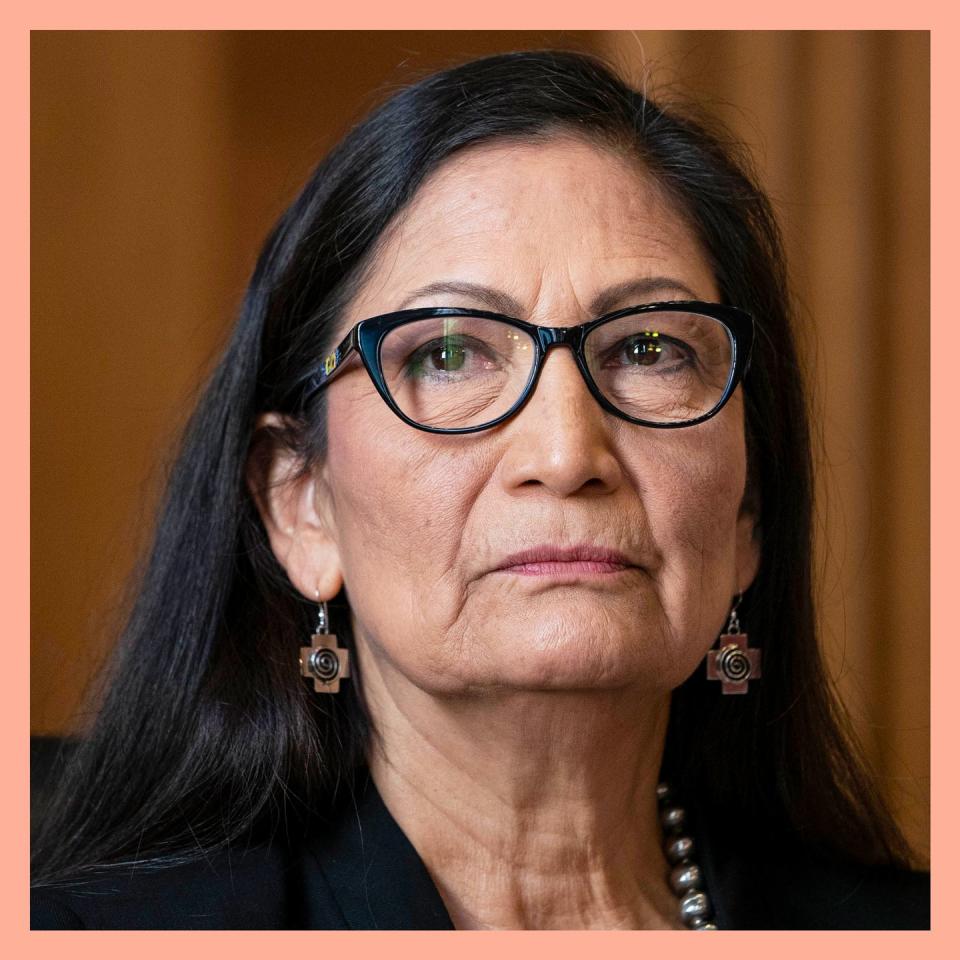

Secretary of the Interior

“As a kid, I moved around a lot and lived on military bases in Virginia and California. Many times I was the only Native girl in the classroom. Once while walking home, a schoolmate stopped to tell me she hated me. She told me I had a fat head, fat legs, and fat braids. I was built like any other kid, but I was one of the only brown kids in school. I went home, and I didn't tell my mom.

It wasn’t until I was older when I realized that our family history was different than others. I interviewed my grandmother during college for a writing assignment, and she shared the trauma of being separated from her family and being forced to live at boarding school, away from her traditional home. A profound realization came to my mind: everything she sacrificed and lived through enabled me to strive to be anything I wanted to be. I embodied the dream she had for her family, and now, I see it as my responsibility to leave a ladder down for future leaders.”

DREAMer, immigrant rights activist

“I babysat for this lady. The kids I babysat and their friends would say things like: ‘You’re Mexican, right? Do you like tacos?’ My body would go numb because it was the first time I went through it. There were many other incidents growing up. My teachers would say, ‘You must be Mexican.’ A classmate said, ‘Put some hot sauce on it, you like hot sauce right?’ Things like that don’t sound serious, but they are, because it’s about my identity. It’s not until now where I’ve had the time to reflect and be like, ‘Well damn...I did face a lot of shit.’

Having DACA, I knew I had to bust my ass, because I was going to be doubted. We’re not set up to make it. I tried not to talk about racist moments I’d experienced because I'm not going to allow that to swallow me. I will fight, because this is for every single person that feels numbed from the violence that comes from racism. That’s the fire that was within me.”

Criminal justice reform advocate; author

“Growing up in Jim Crow Mississippi in the 1950s and ‘60s I never thought much about racism. But in the summer of 1962, after I turned 7, that changed.

My mama let me spend a week with her sister, Aunt Took. She worked as domestic help for the white folks whose place she and her husband lived on. The white folks had a daughter named Linda. We became two peas in a pod. I’d never had a white friend before, and she’d never had a Black one. That Saturday Linda was having a birthday party. My aunt told me to go to the back door and knock. Linda’s mama answered. Linda spotted me and squealed, ‘Marie!’ I started to run past her mama when she put her arm out and stopped me. She said, ‘You just wait right here on the porch while I get your food.’ She came back with a cracked plate that had a smushed cupcake and a cold bologna sandwich.

When I told my mama what happened, she looked at me very sternly and said, ‘Ain’t nobody better or smarter than you just because you a colored girl. In fact, you way smarter than most.’ My mama believed in me, so I believed in me.”

Field organizer; Executive Director, North Dakota Native Vote

“I'm an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, and I grew up 60 miles south of Bismarck, North Dakota. I'm the youngest of 12, and my youngest memories were when my dad would pile us kids in the old station wagon and drive into town. One summer, my dad told my twin sister and I to stay nearby a local museum. We were 6 or 7, looking through the windows of the museum when two white boys both came up to us and in unison said: ‘What are you dirty Indians doing?’ That same day, dad was taking us to get ice cream before we left. As we were backing out of the parking lot, an older white gentleman started yelling racial slurs out the window at my dad. ‘Watch out you stupid Indian.’ I remember it clearly. We need to stop being a society of silent bystanders. When some of the most horrible things happened to me, nobody stood up.”

Trans rights activist

“It was a long time ago, and I had my sister with me at that time. We went to what was supposed to be a classy restaurant in downtown Chicago. They wouldn’t let us in. I found out later they didn't allow Black people there. I was really struck because I genuinely thought every place was open to us, and I didn't see why my color would have prevented me from having access to a place. It really rocked my world, and it's something I think about a lot now. It changed my whole perspective, because I think if that had not happened, I would just have lived my life. But it did happen, and it made me angry. So I changed the way I go about things. I moved to New York, and I was one of the many Black girls that stood up against the oppression of transgender people. I'm going to fight, and fight and fight.”

Executive Director, National Nurses United

“When I was in first grade, a group of kids from my predominantly white, working-class neighborhood would surround me at recess and call me names. One name I understood: ‘beaner’—though I didn’t know why this would be a bad thing. When my mom wasn’t tired from working, she would cook frijoles de la olla, sometimes with chorizo, and it was heaven. I didn’t understand the other word the kids called me: ‘greasy.’ Their cruel taunts pushed me inward, and my teacher would tell my mom, ‘Bonnie always spends recess alone.’ Thank goodness it wasn’t that way inside the classroom, where I loved my teacher.

It’s important to have trusted adults in your life. I eventually asked my dad—a self-taught intellectual—why the kids called me 'greasy.' He explained they were mocking a fundamental ingredient of our food and our heritage. 'What they are doing is wrong,' he said. 'We are Mexicans, and lard is fuel. It keeps us going and strong. So they are attacking us for surviving.' That wasn’t the last time I experienced racism, especially as hospital employers exploit prejudice and bigotry to divide nurses and prevent us from unionizing. But I never forgot what my dad said about Mexican food literally giving us power. I recently made my own masa with bacon lard. It was magic.”

Lawyer; Associate Director-Counsel, NAACP Legal Defense Fund

“I grew up in an Astoria housing project in Queens. When I got to fifth grade, my mother was extremely dissatisfied with the level of education at my school, so her coworker offered to let us use her address to go to a predominantly white school. At the time, I was very into writing poetry. I submitted a poem for a school competition. When the teacher read the poem, she rejected it and told me that there's no way I wrote it. My mother knew I did because she was there when I sat down at the kitchen table to do it. She went up to the school and demanded they accept the poem.

The lesson for me was never let someone else's judgment of your potential dictate what you do. It’s that type of defiance and hope that you need in life. Work around racial injustice has always fueled and infuriated me—racism put a fire in my belly. Now, it’s my life's work. To eradicate it, to understand it, and to transcend it.”

Environmental health advocate; 2020 MacArthur Fellow

“I grew up in Lowndes County, Alabama, and attended Lowndes County Training School for high school. Whenever I would state my school’s name, people outside of the South assumed I was in a school for bad children. I learned this from Senator Edward Kennedy, who explained it to me during a visit to his office in the summer of 1975. When I told him the name of my high school, he informed me that, in many places, the term ‘training school’ was synonymous with schools for delinquent children. The term carried a stigma in the South, where Black children attended training schools and white kids attended high schools. When I went back home, I told my parents I did not want ‘training school’ to be on my diploma. At the age of 17, I went with my father and another activist, Reverend Arthur Lee Knight, to present at the school board meeting. I fought to change the name of my high school—and won. When I graduated, Central High School was on my diploma.

Lowndes County has long been a hotspot for activism. It is the county in which the organization that inspired the original Black Panther was formed. Growing up surrounded by this legacy shaped me as a young activist and informed why I continue to fight the remnants and symbolism of the confederacy that still exist–not just in the South, but throughout the United States. I proudly share my megaphone.”

Skateboarder; artist; activist

“I was lucky in my childhood because I grew up in a neighborhood where about four of the 14 families on the block were Asian American, and so I don’t have many specific experiences with racism. But I do remember being on the playground in elementary school and being called ‘Jap.’ A few years after that, I remember wishing the shape of my eyes looked different. And then in high school I saw some Asian girls that would actually put tape on their eyelids to make their eyes look more caucasian. It was a weird feeling to want to look like somebody I was not.

So although I didn’t specifically remember too much, I think that experience on the playground went deeper than I fully realized. It’s such a powerful slur that anybody like me who is of Japanese heritage really understands it as an attack.”

Co-Executive Director, Freedom Inc.

“I was 8 or 9 years old waiting to go to school at the bus stop when one kid said to me, ‘Go back to China.’ We got into an argument because I knew I wasn’t from China. That memory is so vivid, and almost 40 years later I still remember the location of the bus stop; on this corner in the south end of Madison, Wisconsin.

I think coming to America as a refugee child from Laos—being displaced from a country that does not want you, into a country that you feel foreign to—impacted me because even at that age people assumed I didn't belong here.

That’s why I’ve always aligned myself in social justice movements here in America. I find solidarity with other people of color and understanding that the same hate that caused a little 8-year-old to say something like that to me, is the same hate that allows police officers to kill Black people and for Indigenous women to go missing. The best thing you can do is not be silent.”

Chief of Staff, Senator Tim Scott

“Something that still eats at me happened when I was older, in my early 20s, in law school at the University of Michigan. A crew of us decided to go to the football game, and we're walking together along the path to the stadium, when all of a sudden we hear somebody on an electric megaphone shouting racist obscenities. I remember all of us stopping our conversation and looking at each other. I had long ago learned to not be bothered by words, particularly racist words. But what really upset me was that hundreds of people were walking and heard this guy on the megaphone, and not one person told him to shut up.

That event along with other things that have happened throughout my life have definitely impacted my path and where I am today. I just make it my goal to show the world my faith and who the Lord has made me to be. I truly believe that he made me this race on purpose, and he built me to endure the tribulations that come with this race. And I think part of my calling is to help people who look like me get to where they want to be, and not let something as silly as a boy on a bullhorn hold them back.”

Artists, Creatives, Entertainers

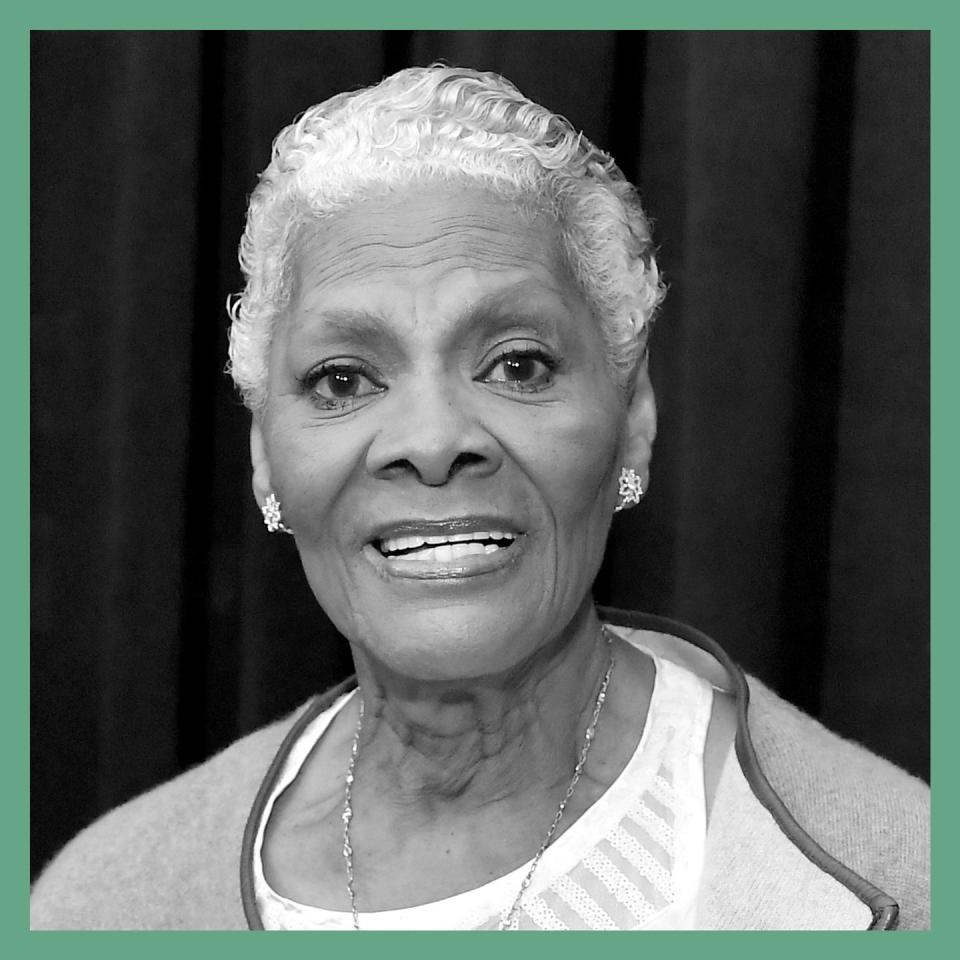

Singer

“Around 1964, I was on tour with Sam Cooke in South Carolina. We were on the bus prior to our sound check, and Sam said he’d treat us to lunch. Another woman and I were designated to place the order. When we went into the restaurant, we sat down and were immediately told to get up. This waitress shuttled us to an area where she took coffee breaks, and when we tried to order, she was rude.

Me and my big mouth, not accustomed to being treated that way, told her, ‘You can take this and shove it up your...’ and walked out. A couple minutes later, a police officer came and said: ‘I’m here to find the two gals that were insubordinate to the waitress.’ Sam decided to speak up and said: ‘Officer, first of all there are no gals on this bus. There are ladies and gentlemen. And by the way, this happens to be my bus and you are not invited on it, so will you please leave.’ I almost got us arrested, but I had to let that lady know she couldn’t talk to me that way.”

Director; screenwriter

“It happened in middle school. I was in art class and the only Black student in the classroom. Three boys drew pictures of Black men in nooses and taped them up. I remember the art teacher saw the pictures, glanced at me, took them down...and that was it. No reprimand, no discussion. I knew how violent the gesture was, and I remember feeling so unprotected, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to fight it then. What I wish I could tell little Gina is that your voice matters. Given all the things I had to face growing up, my success now is a middle finger to all of the people who made me feel less than. It’s one of the things that fuels my fight. I just wish I could talk to that teacher and teach her a different way to respond in the future. But maybe a teacher will read this piece now and be inspired to do the opposite.”

Broadway actress; singer; author

“I’m from a small town in California. From a very young age, I loved music and Broadway. When I was 18, I booked my first agent and thought, ‘This is it. Now I can live my dream.’ When I went to their office to sign contracts, they took me into this side room and said: ‘We think the name Gonzalez is going to hinder you from getting jobs because it’s too ethnic.’ They asked me to come up with a different name. I remember feeling terrible and wanting so badly to belong. So I came up with Mandy Carr. When I went home and told my parents what happened, I felt bad they’d made me feel my family name wasn’t enough.

I thought about my abuela who came to this country and worked so hard to be a part of it. I thought, ‘How dare this woman try to erase a part of who I am?’ I went in the next day, and said, ‘I know I told you that Carr is spelled with two ‘r’s’ but Gonzalez is spelled with two ‘z’s,’ and I'm keeping my name. My name is Mandy Gonzalez.’”

Comedian; actress; author

“In second grade, I moved to Pomona, California. At school, all these boys would call me monkey, and nobody would play with me except this girl named Amber, who I met on the walk to school. Even though Amber’s dad didn’t want me in their house, she didn’t let that stop her from hanging out with me in their backyard. One day she got a playhouse in the backyard, and she said: ‘My daddy might not let you in our house, but you’re always welcome in my house.' See? I got them to get me a house.

I was in Pomona recently shooting a TV show, and I saw my old house, and the house that Amber lived in five blocks down. I want to say thank you to that girl Amber, because she stood by me regardless. That meant that world to me. I remember her name to this day.”

Television host, The Real

“I grew up in a three bedroom home with 15 other people, because we sponsored family from Vietnam. Within those four walls, I never felt more proud. But I’d go to school and people asked if I spoke English; they’d pull their eyes slanted to mock me. When I was in high school, the word go*k’ was spray painted on my aunt’s car. I didn’t know what it meant, but I immediately knew it was about us. I remember her asking me—because I’d been translating words to her—‘What does that mean?’ I hid my face because I was afraid she’d see how embarrassed I was. She came outside with a pot of hot water and a Brillo pad sponge and started scrubbing. I helped her.

One of my best friends was Black, and I saw her moments of racism too. The kids walked by her house and yelled the n-word super loud and threw rocks. They asked her why she was hanging out with a ch*nk and why I was hanging out with an n-word. Unfortunately, I learned about race through moments like that—instead of those happy memories of being at home that made me proud of who I am.”

Fashion designer; influencer

"I was maybe 6 years old, and we packed lunch for school. I remember a couple of kids always teasing me, like ‘Oh my God, your food smells’ because my mom packed Korean food. The next day, the teacher told my mom that I couldn't bring that food anymore. Other kids and I were allergic to peanuts—I had to be rushed to the hospital like three times because I was allergic to peanuts—and they didn't ban peanuts. Yet they banned my mom's food. I remember thinking, okay, I have to bring sandwiches.

That's when I learned to be ashamed of my culture. I didn't have any concept of it, but I realized at 6 that my people's food was inferior to my white peers’ food. My whole childhood, teenage, college years, I still always felt inferior. I became proud when I started getting recognition for who I was in the fashion industry. I wish I didn't have to feel so ashamed. I do have that sense of like, Oh, man, I really wish I embraced it more. I really wish I could have been proud of both cultures.”

Miss USA 2019; attorney

“I identify as a Black woman, but my dad and stepdad are white; we had a really mixed family. In elementary school, kids would tell my siblings and I we could pick Black or white, but we couldn’t identify as mixed. That shaped my entire identity because when I was growing up, there wasn’t a lot of representation for biracial people. There weren’t even boxes for us. You could pick Black, white, or other. I remember joining ‘Mixed Chicks’ groups on social media, but after a while, being a Black woman was just how I identified because of the way people treated me.

I looked up to Halle Berry, a biracial woman. I remember wanting to cling onto somebody who knew what their identity was, whereas I felt lost because I just didn’t know what I was supposed to do. Now as Miss USA, I try to be more sensitive to how people want to identify, even beyond race, because I was told how I should identify, and it shaped the way I saw myself. I want people to be able to define that for themselves.”

Makeup artist

“I was born in the U.S. but my parents came here as immigrants, and the rest of my siblings were born in Vietnam. Growing up, my parents told me we were guests in this country, and we're lucky we even made it here. It’s the white man's world, we just live in it. So instead of being told you’re special, to hold your head up high and stand up for yourself, as a child I watched my parents being talked down to, called ch*nks, discriminated against and abused. And not once did I ever see my parents curse somebody out. My parents are now retired, and they're very successful. But to this day, it's affected my self-worth.

Talking about it makes me so emotional because my parents came from a generation where they were not taught self-love. And then they moved to a country where they were viewed as less than, and that's some generational trauma. I’ve channeled a lot of it through my career in beauty, because feeling beautiful is empowering. Now, I hope I come back in my next life Asian again. I hope I come back with silky skin, thick hair—I want to do it again.”

Miss Teen USA 2019

“I wore singles in my hair to school, which are really long braids that have synthetic hair. The kids at my predominantly white elementary school thought it was so interesting because they hadn’t seen that before. It made me feel like I stood out, and not in the best way, because nobody was ever interested in me, but in my hair. As I got to middle school, I straightened it so I would fit in, and people would say things like, ‘You may be mixed, but you’re white’ or, ‘You don’t talk like a Black person.’ Later, I transitioned to natural curly hair, and Black people would tell me I’m not Black enough.

It was little things like that I always had to go through. But ‘just hair’ can have an effect on who you are. It took me so long to get to where I am today and be comfortable with myself. Being Miss Teen USA is what made me realize how big of a deal hair is, and how it helped shape my identity. Representing women of color now, both by who I am and the way my hair looks, has been amazing.”

Artist; barista

“I’m from Hawaii, and I grew up in a predominantly Asian community. The kind of racism I experienced, I felt more from my Filipino family. Our parents talked about not getting too dark, not playing in the sun—we had skin whitening soaps. For a long time, I couldn’t figure out why; when you grow up in Hawaii, you can’t help but play in the sun. A lot of brown people think ‘I can’t be a racist because I’m brown.’ But when I sat down and really thought about it, I also perpetuated a lot of those things growing up. When my cousins first moved to Hawaii from the Philippines, I tried to help them assimilate because I didn’t want them to struggle, but I made them feel less than because I was trying to force them to fit in. It makes me so embarrassed—and makes me want to work harder to be the person I needed when I was a kid.”

Broadway actress

“I went to first grade at a school that was predominately white. I remember we were all playing Star Wars one day, because the movie had just come out. I asked my mom to put my hair in little cinnamon roll buns like Princess Leia, but the kids said: ‘No you’re Black, you can’t be Princess Leia. You can be Chewbacca.’ That’s what they told me, seriously. It devastated me. I was only five. Those first memories of self- worth, of being told by these kids that I was less than...it’s something that seeps in at an age when the skin is so soft, literally and figuratively. I’m very aware that it’s deeply embedded in my psyche. Wow. I’m 50, and that’s still in my heart.”

Blogger, Hill House Vintage; digital creator; stylist

"1980s London was wonderfully diverse, but as my parents' circumstances improved we moved up the property ladder into less diverse neighborhoods. Unfazed, I had grown up with the sound of three P’s ringing in my ears: pride, positivity, and power. My parents believed I should hold my head high in every circumstance, view change with positivity, and remember I was powerful enough to excel anywhere.

Walking home from school one day, a boy meandered ahead of me. Repeatedly turning to look, he slowed down and uttered the word ‘n****r.’ It felt like a short, sharp slap followed by silence. Neither of us broke our pace, but for a few seconds we looked at each other in shock. He seemed to surprise himself more than me, and I continued past with my head high. I decided not to tell my parents. They’d want to find the boy and tell his parents, and I was suddenly aware that a confrontation might inflict more harm on them than a foolish boy experimenting with cruel words could inflict on me. That day another ‘p’ was added to the list: preservation."

Pianist

“I grew up in a rural town in Pennsylvania outside of Harrisburg, and I was one of the only Asian American people in my school. I’d bring Korean kimbap for lunch. The kids would say, ‘Ewwww, what are you eating?’ I quickly learned how to navigate that, because my parents had done such a great job of instilling Asian cultural pride in me. After a couple of times, I said, ‘Actually, this tastes like potato chips, and it's good for your hair. Look at my long, silky hair.’ By the end of the year, my mom was bringing seaweed packets to school for my classmates.

That made me understand the importance of sticking up for yourself and educating people on your culture. Now in my 30s is the first time I'm scared to be Asian when I go outside. All of the anti-Asian rhetoric and hate crimes—more than during my childhood—today is the day that I'm the most afraid to be Asian. And that's a completely different feeling.”

Cake designer; YouTuber

“I’m biracial and being born in the 70s, back then it wasn't as common. I come from a loving family, so the fact that my parents were two different colors didn't dawn on me. That was my normal. But when I was 16, I had a boyfriend I thought was the love of my life. We were going to a dance, and on the night of, I was so excited because I was going to his house to meet his parents. When I got there, his father got up from the dining table, left the room, and never returned. I found out my boyfriend had only told them one half of my heritage, and not the other.

When we broke up I remember having a conversation. He said: ‘You know, we have to think about the way our children would turn out.’ I remember thinking, ‘You mean like me?’ It was like a brick dropping on my head. For the first time, I thought, ‘Am I supposed to be ashamed of who I am?’ It’s unfair to sit here in my 40s and judge my 16-year-old self, but I wish I had the self-confidence and self-respect to stand up for myself.

Wherever he is now, I hope he reads Oprah Daily.”

Photographer

“When I was in my high school choir, we went on a tour of the South, performing at different churches and concert venues. I remember once, while we were hanging out in the lobby of a hotel we were staying at, we were asked to leave. We were all Black kids. Not being loud or causing a disturbance. Just hanging out. There were other white people in the vicinity as well, but they weren't asked to leave...we were. I grew up in Chicago, which is an inherently racist place, but I had never really experienced overt racism until I went to the South.

As a Black person, I've been dealing with overt and covert racism for as long as I can remember. It becomes so much a part of your daily life. That moment in the hotel lobby was just another drop in the bucket. You get to the point where you just process it and move on because it's not possible to function in life if you're constantly holding on to all these instances of racism."

Art curator

“I was one of those kids whose parents made sure to buy Black dolls, watch Black TV shows and affirm my identity. Years later in college, I decided to study art history after doing an internship at the Studio Museum in Harlem. My own entry point into a traditional art world was in a very Black space. But when I got back to campus, one of my art history classmates and I got into this dispute about representation, and what it meant for this artist who did a performance piece that was related to racial identity. The next day, my white professor said to me: ‘If you wanted to be in a classroom with other students of color, you shouldn’t have studied art history.’ He had submitted to the idea that his classroom would always be full of white students, and I was a disruption to that ideology. That moment always sticks out to me in relation to the work I do now, because I’m really invested in making sure people understand that art isn’t just for white people. It’s the duty of all of us to make sure young folks don’t have to fight as hard.”

Artist; baker; activist

“My earliest memory goes all the way back to preschool, me being bullied through one of those diamond, metal-shaped fences near the playground. This older white boy was trying to kick and punch through the fence, using his fingers to pull back his eyelids and taunt me. He called me a ch*nk multiple times, and I was too young to understand what was really going on. This sense of othering was very eye opening, as far as how early on in our lives we have a concrete understanding of people based on how they look.

Those experiences were somewhat compounded by an absence of people who look like me or whose lived experiences mirrored mine in my textbooks while growing up. That's really what put me on my path now, using cookies as a platform for introducing other Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who I wish I learned about while growing up in this country.”

Model

“When I came to St. Cloud, Minnesota in second grade, I didn’t speak English. I spoke fluent Somali and Swahili, and I’d left behind a lot of friends in the refugee camp I grew up in. Being one of very few Somali students, I do remember getting bullied. The kids would try to pull at my hijab, a boy threw water at me, they’d call me smelly. I’d tell the teacher, but no disciplinary action was taken towards the students. I noticed that and thought that applied to me, too. One day at recess, I fought back, and I got suspended for about a week. I couldn’t fight back the way they did because I didn’t have the same privilege afforded to me.

I learned to beat them where it mattered—academics. I had a point to prove: ‘Yeah I came to this county not speaking a lick of English, but I’m still going to outdo you.’ Thinking back, did all my life stem from that moment and wanting to show those kids and teachers? I would say it all worked out because at the end of the day, I validate me.”

Floral designer

“Growing up in Omaha, Nebraska, my parents would drop me off at the shopping mall with friends, and I had this feeling that I was being followed in various stores. I picked up quickly that the store clerk assumed I must be up to something and thus trailed my every move. I felt like I didn't belong. I was 13 years old. As a young Black girl, I developed a heightened awareness of my own surroundings, the space that I took up, and how I felt I was perceived. I came to realize how unfair it was that my simple presence as a Black person in a public space could be seen as a threat. It weighs on you.

It goes without saying that racism, unchecked bias, and microaggressions are insidious and they can seep into our lives. But I do think that community and the momentum we get from lifting each other up so that we can all eat and thrive, is 10 times more powerful than anything that works to keep us down.”

Radio personality, Hot 97

“My parents are from Guatemala, but I was born and raised in Los Angeles. Growing up, I spoke better English than my parents. One time when I was about 12, we were shopping at a little convenience store, and I heard my mom arguing with the cashier. My mom was having trouble articulating what she wanted, and the lady was loudly and aggressively saying: ‘Speak English, speak English. You don't understand? Speak English.’ My mom suffers from social anxiety, so it completely paralyzed her; she was in tears. I remember rushing to the register and being so livid at the cashier for talking to my mother like that. All the cashier would say to me was, ‘Well, we're in America. We speak English here.’ It boiled my blood. Growing up, we had to try to figure stuff out for our parents. It's a different sense of responsibility that you have while trying to find your identity as a kid in America. Now, I work on a morning show where I’m very lucky to be able to express how I feel. We talk about it all—the Latino community, immigration, sexism, Black lives matter—and it’s a blessing.”

Opera singer

“When I was in high school, there was a day that changed my life forever: September 30, 2003. It was homecoming spirit week and every day, you would dress up as something different. One of the days was called ‘Phat Tuesday.’ People came to school in gold chains, cornrows, gold grills, afros, jerseys, baggy pants—including teachers. At the time there were about five Black students; you can imagine our discomfort. I wrote a letter to the whole school and the dean read it at a school assembly. People came up to me afterwards, and they were just like, we're so sorry, we didn't know. That moment really changed me for many reasons. I didn't even know that I had this voice in me, but that was the first instance where I was like, ‘Wow I have a voice that's bigger than mine.’ It was about our collective humanity, and breaking down these ingrained stereotypes. And my voice is bigger than me.”

Musician, Japanese Breakfast

“One of my most shocking and direct experiences with racism was when I was in Greenpoint and this Italian guy asked if he could bum a cigarette. He was very drunk and rude to my friends earlier, so I said no, and then he called me a ch*nk under his breath. I just couldn't really believe that he had called me that so I was looking at him incredulously, and then he repeated it and was saying: ‘That's right. I called you a ch*nk.’ Thankfully I was with a large group of people, so I felt comfortable and protected enough, and I did throw water in his face.

That was the first moment where I felt safe enough to actually do something and not just laugh it off or ignore it. I was really proud of myself that I didn't just internalize what had happened. Something clicked in my brain that was like, ‘That's not okay.’”

Singer, actress

“When I was about 7-years-old, my dad had a family softball team where we’d go to weekend tournaments. We played music, barbecued in the parking lot with all the kids running around—it was awesome. But there was this one tournament—we won—and a man from the other team starts a fight with my uncles. I remember him saying so loud: ‘You people think you can just come in here and do what you want.’ A lot of profanity was thrown around. I was so confused, because we didn’t do anything wrong.

Even now, I remember working on one of my first films and being the only brown person at the table of white male executives. It was a bittersweet feeling. I was proud because I was doing everything I ever dreamed of, but at the same time, it was really lonely. Now my biggest mission is to make sure that I share the light—to practice what I preach, and apply it to what’s happening behind the cameras. There’s an opportunity to represent something much bigger and more impactful than what’s trendy.”

Comedian

“The first time I remember being called a n****r I was in first grade at St. Peter’s Apostles Catholic School. I was playing kickball and this kid named Scott didn’t like the way I was playing, so he said: ‘Learn how to play you n****r.’ I can also remember a friend who was Italian American. At the time, she loved Puerto Rican and Black guys, and would always sneak out to go see them, but say that she was with me instead. I remember her mom came to my house one time and told me: ‘You made my daughter a n****r lover.’ It definitely took a while to get through it. It’s a slow simmer of loving yourself. But I don’t want to always live in a painful place, so humor gets me through that shit. Don’t let anyone take away your joy.”

Chef

“I was in second grade, and the teacher asked me where I was from. I told her I was from Bangladesh, but she kept insisting I was from India, telling me Bangladesh wasn’t actually a country. I got sent to detention because I wouldn’t just say I was Indian. They called my parents, and my mom had to pull down the map and show them where Bangladesh was. I’m never going to forget that. My mom always handled this stuff really gracefully, and she got everyone to laugh, but it’s one of those things that made me realize I can’t just listen to authority figures. They don’t always know what’s best, and it’s important to push back. Now that I’m older, I think I’m more direct than my mom was. She set a really great example for me in the way that she was always able to speak to people in a calm way and push back. But it’s our turn to push a little harder.”

Owner & Executive Chef, Brown Sugar Kitchen

“I can't remember the first time someone called me n****r, but I do remember telling my parents, and my dad was like, ‘Oh, that just means they're ignorant. And you can call them one as well, because that's what the word means.’ They tried to take away the connotation that it had anything to do with my skin color. But I remember very clearly sitting in the cafeteria and a good friend of mine was talking about a TV show character. She said, ‘Oh, you know, that guy, he's the n****r in Welcome Back, Kotter.’ She clearly didn't mean it negatively, but she had heard the word at home and thought it was okay to say in front of me. It was shocking and I think it took me a while to process it, especially at that age.

I experienced disappointment at a very early age, and it gave me a thick skin.”

Miss Universe

“I grew up in the Eastern Cape in South Africa. During the apartheid era there was a lot of segregation. Black people were taken hundreds of years ago and moved to certain parts of the country while white people lived in their own fabulous part of the world. Because of this I grew up amongst Black people in a village and wasn’t exposed to the other side of the world—where everything glittered and everything was gold. So many underdeveloped and impoverished parts of South Africa are occupied by Black people because of the apartheid era.

I think growing up, it’s very demoralizing, because it crushes your confidence and your dreams of wanting to be anything. I still get imposter syndrome. Am I supposed to be here? Am I deserving of being Miss Universe? But I’m more assured each day that I wake up, that I am supposed to be here. It is my responsibility to let other women who are like me get into the same door that I did.”

Writers and Journalists

Writer

“In one of my college history classes, I handed in a paper, and the professor told me that I should get tutoring for my remedial English. That was very upsetting, and I felt it was unfair. I had just won a major university prize for nonfiction and later that year, another one for fiction writing, and I wasn't even an English major. So I believe he said that to me because of my name. Of course, I had a sassy comeback: ‘It's not that I don't know how to write. It's that you don't know how to read.’ I withdrew from that class.

If I hadn't gotten those writing prizes, I wouldn't have felt such a willingness to clap back at his nonsense. I think that for many people, comments like that from esteemed, tenured professors would be incredibly crippling. So I tell this story because I want younger people to feel a sense of resistance and vigilance when your creativity and gifts are diminished by racism and bias.”

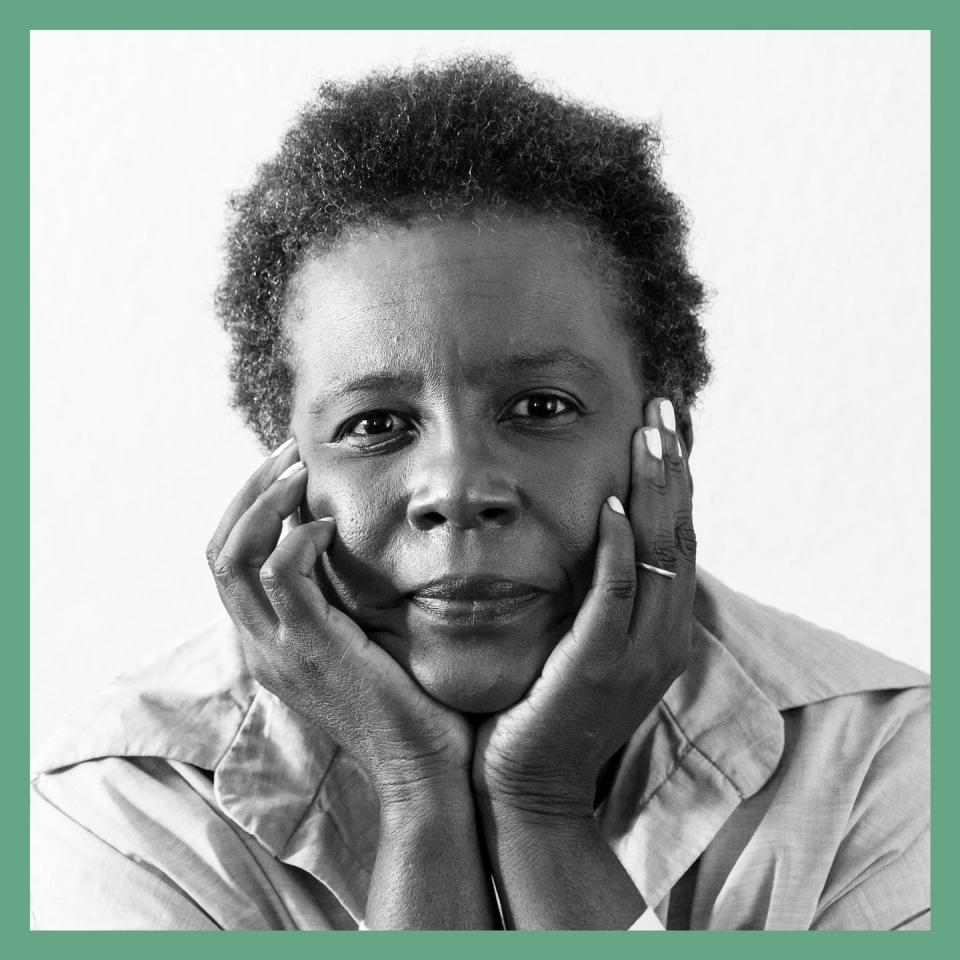

Poet

“When I was a kid, I lived on a block where we were the only Black family. One day out of the blue, a mother in the neighborhood drove her car as my mom and I were walking down the street. She said, ‘My daughter just graduated from high school, and we have all of these uniforms.’ They were the older, chic uniforms I loved. My mother refused them, and I was devastated. I asked her, ‘Why did you say no?’ And she said: ‘Because, she knows where we live. All she had to do was come to our house and ring the bell, introduce herself, and say exactly what she just said, not corner us as we're walking down the street.’ That was one of those moments where I understood that it had to do with respect. It had to do with Blackness and whiteness. What my mother wanted first was the recognition of humanity. It was an early lesson, but a good one.”

Senior Executive Editor, National Geographic

“I remember being chased around the schoolyard, kids circling me saying ‘Wah-wah-wah-wah, wah-wah-wah-wah, Indy the Indian, Indy the Indian.’ They were making fun of me for being Indian, but it wasn’t even the right kind of Indian. Even then I was struck by the ignorance; I tried to school the kids about how I was Indian from India, not Native American. It taught me at a young age how important education is, and how important the stories that we tell ourselves and our children are.

It’s been a wonderful journey from being that little girl in the 70s and 80s to now being Senior Executive Editor at National Geographic, because our entire mission is not just a journalistic one. It’s also very tightly tied into education—showing people what a big world is out there, that we’re all human, and we all have valuable cultures to bring to the table.”

Co-host, CBS This Morning; Editor at Large, Oprah Daily

“I lived in Turkey as a kid, and I have a very distinct memory from elementary school where we were learning about Abraham Lincoln and slavery. A kid said to me: ‘If it wasn’t for Abraham Lincoln, you would be my slave and I would tell you what to do.’ So I went home, told my mom what he said to me. I asked her: 'Would I be his slave?' My mom said ‘He has no idea what he’s talking about.' That could have been a very traumatic thing, but it wasn’t, because of the way she handled it for me. That was my first realization that I was different, and ever since then, I became very mindful of race. But it wasn’t something I focused on. I’m not going to be defined by someone else’s attempt to negate me or make me feel lesser than. I refuse to give in to that.”

Writer

“The first time I saw myself in the eyes of a white person, I was 25 at a boyfriend’s Halloween costume party. He worked for a brokerage firm; he was the kind of man who wore suits and ties, very successful. He was so far away from my mundo and I from his.

Without being aware of it, my cousin and I picked the most stereotypical costumes that Latinas could possibly wear: I was Carmen Miranda and my cousin was a Spanish flamenco dancer. In the middle of the party, my boyfriend’s preppy coworker suddenly went into hysterics saying her purse was missing. We thought she misplaced it, but she was implying someone had stolen it. My cousin and I were so inocente, we didn’t notice we were the only people of color at the party until that moment. It was as if someone had let loose some sort of poisonous gas when we suddenly realized, ‘Oh, my God. She thinks we have stolen her purse.’ Her purse was found, of course. And by then she was apologetic, but it was too late. That has always stayed with me.”

Playwright

“These memories start when I'm about 4 years old. I’m a white-passing Latina in a family of brown, Puerto Rican women, so I was identified differently from my mother, aunts, and grandmother. When I’d go to bodegas to get snacks with my mom or look through antique stores with her, I saw that my mother was being followed and looked at suspiciously, while I was getting tremendous respect. That is remarkable for a 4 or 5-year-old to be treated differently than her mother.

That's why I became a writer. My passing privilege gave me a clear view of the differential treatment. I witnessed it many times, and I’d hear bigoted statements from white peers and elders who thought I was ‘safe.’ I thought, where are the stories telling who we are, where are the stories speaking of our complex humanity? I couldn't find them. They certainly weren't assigned to me in school. I didn't see them in the movie theater or the bookstore. So I thought, I know these stories. I'm going to tell them.”

Journalist

“I was teased every single day of my entire life as a kid. It started when I was first called ‘risa ring’ in elementary school. And it wasn’t just risa ring, it was ‘Oh, risa ring’ [in a mocking accent]. I don’t think it was malicious, because most of the people who did it were my friends. I laughed it off, but sometimes it did send me home crying, because when you’re a kid, the last thing you want is to be different from anyone else. There was also an incident when I was about 21 years old. I was working as a reporter on Channel One, and I was chosen as one of Rolling Stone’s ‘Hot Reporters.’ To have been chosen was awesome. Right after it happened, someone at my workplace cut it out and drew slanted eyes over the eyes and wrote ‘Yeah right.’ It never really goes away.”

Journalist

“The first act of discrimination I experienced was when I was almost taken from my mother by an immigration agent. We arrived by plane from Mexico City, and had to transfer in Dallas to catch the next flight to Chicago. At the Dallas airport, the agent—based on those anti-Mexican, dirty Mexican laws in the state of Texas that basically said any Mexican coming into the United States had to be searched—was looking over my body. I had a rash, and he said I had measles and had to be put into quarantine, so they were going to keep me.

My mother basically had a meltdown because they tried to take her daughter. I think a lot about the seeds that are planted in moments like this. The most difficult part is how a memory can become cellular. When I understood that, I was like, ‘Now I know why I do what I do as a journalist.’ One of the central things is verbalize it, talk about it, paint a picture of it, and realize: you’re not the only one.”

Senior Director, Editorial and Strategy, Oprah Daily

“My dad is Black, and my mom is white-presenting Puerto Rican. I realized early on that I was different from the other kids at my mostly-white school. When my mom would pick me up, they’d ask if she was my babysitter. On the playground, a favorite pastime amongst the boys was daring each other to touch my frizzy ponytail. But it wasn’t until fifth grade that I understood the word racism. We were reading Huckleberry Finn in English class, and we’d take turns reading passages out loud.

When we got to a section with the word n****r, my heart started beating fast. Before I knew it, the teacher was asking me, the only Black girl, ‘Who wants to read this? Arianna?’ My classmates started snickering. I started to read the passage quietly, but I couldn’t finish when I got close to the word, so I asked if I could pass. She called on someone else to skip ahead to the next part, but for the rest of the class, my classmates whispered and giggled, looking back at me and pointing.

Thinking of that still makes my heart race with anger. If I could talk to my younger self, I’d tell her to speak up and tell the teacher no, or to proclaim that word is not okay to say out loud, in a book or otherwise. But I also know that kind of burden should’ve never been placed on a 10-year-old kid in the first place.”

Digital Director, Harper’s Bazaar

“When I was a kid I had box braids, and the little boys in my school in third grade would make fun of my hair. They’d call me Medusa. Well, their nickname was ‘Medusa Orange,’ which doesn't make sense. It's not the smartest burn if you will, but all these years later, it's stuck with me.

That was sort of my first time thinking my hair in braids is not okay. I felt othered with my hair. Thankfully my parents told me it’s ok to have box braids or cornrows or any of those hairstyles. I think the way it translates to how I carry myself now is I have a haircut that I guess you could say is edgy—a statement. I feel at home in this haircut. And I think that's because I've always paid extra attention to my hair and what it could telegraph because of this moment of racism when I was younger in elementary school.”

Editor-in-Chief, Elle

“The first time I experienced racial discrimination was when I got into my profession. I had a boss that would ‘jokingly’ refer to me as the daughter of Pablo Escobar because I was from Colombia. It was such a harmful way to stereotype me and my culture. I knew they were doing this to undermine and belittle me, and it was painful. There was another time when a superior questioned how I’d gotten the role of fashion director. It was as if there was an inherent uncertainty about my ability. People of color are constantly disproportionally having to prove their worth.

It is already so hard to be a girl in this world, and with the layer of racial discrimination, you add to the barriers that young girls have to break through. Now that I’m in a position of power, I want everyone to feel included, empowered, and to share their thoughts and ideas. I want to be there for the next generation of diverse talent, and I’m going to hold open that door.”

Scientists and Doctors

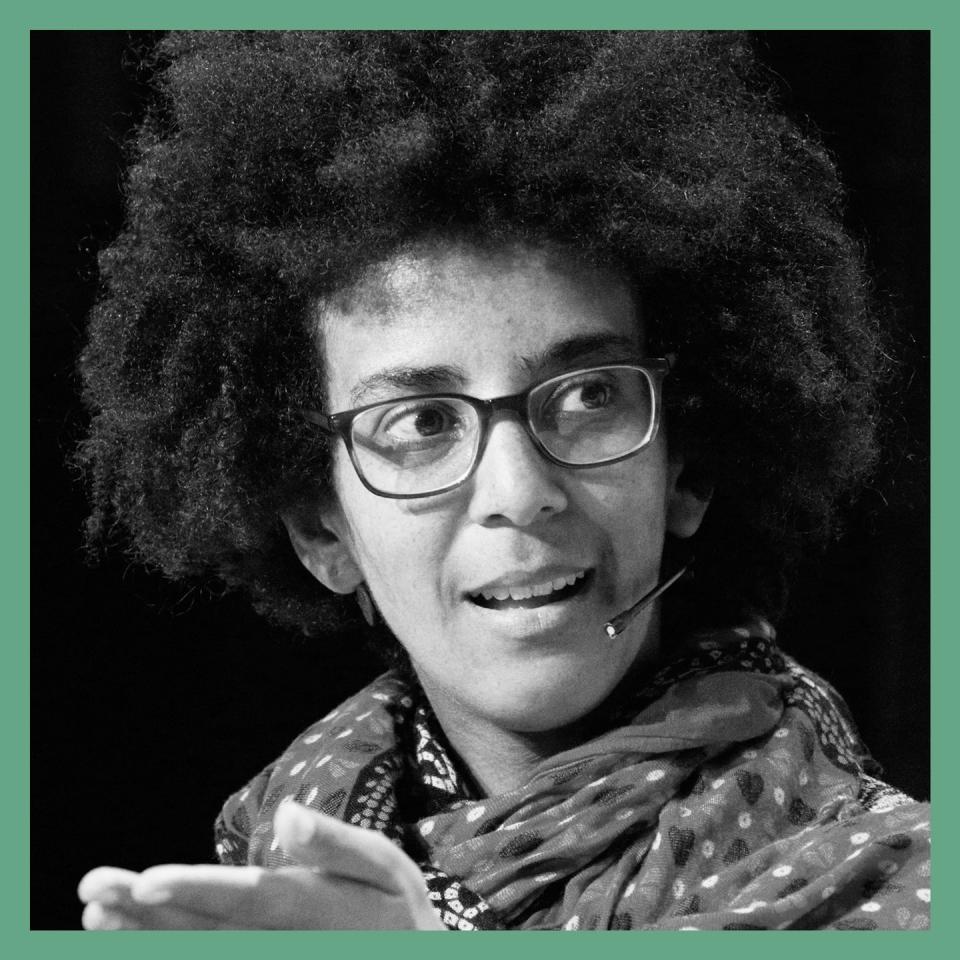

Research Scientists; Co-founder, Black in AI

“I'm an immigrant, and I came to the U.S. under political asylum when I was 16. On my first day of school in America, I went to chemistry class. My teacher explained what he was going to cover that year. At the end of class, I went to him and said: ‘I covered all of this, so can I move a level up?’ He said, ‘I met so many people like you who come from other countries, think they can just come here, take the hardest classes. If you took the exam that these people take, you’d fail.’ I decided not to take chemistry at all. It was battle after battle for two years in that school. My guidance counselor told me I wouldn't get into college. I got into Stanford.

We all face very serious issues because of white supremacy. The way they manifest themselves might be different, but it's the same struggle. Those experiences fueled a lot of the things I do today, including my work on mitigating the negative impact of artificial intelligence, mostly towards people of color.”

Psychiatrist-in-Chief, Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania

“I was raised by a single father in Cincinnati, and I remember him telling me this story about how he lost his job after his wife died. He said he had to miss work to go to the funeral and his supervisor, who did not like African American people, terminated him for missing work that day. I thought, ‘That’s not possible.’ I thought something else must have happened, or my dad wasn’t telling me the whole story. But in high school, this older caucasian man—whose daughter was my classmate—asked me if my father was George Benton? He explained to me that he was the person who fired my father.

He also explained to me that he always wanted to apologize because he fired him for attending his wife’s funeral. He said he did that because he didn’t think Black people should be working in his industry and felt that my father was taking a white man’s job. But I had already internalized this idea that if bad things happened to Black people, it’s because they caused it to happen. We carry these things over time, and if we don’t talk through them, it undermines our confidence.”

Artificial intelligence expert; Founder, The Bean Path

“In high school I was selected to attend a summer program at Phillips Exeter Academy, a prominent private school in New Hampshire.

One night some of us Black students were sitting in the dining hall eating ice cream, laughing, and having a good time. Next to us there was a caucasian male with his wife and kids. He has this disgusted look on his face and eventually he said: ‘Can you please shut up?’ Then he said the n-word. That was the first time anybody ever used that word to my face.

It hurt because coming from Jackson, Mississippi, the civil rights movement was born in me. I knew the impact of the n-word and where it came from. That whole summer shaped a lot of my perspective. It exposed me to a lot of great things, but I also realized the challenges I would face going through the world.

My mission now is advocacy that helps bring more people of color into technology fields. Everybody has something of value to bring to the table.”

Social psychologist; professor

“I remember an incident at my all-Black school in Cleveland, Ohio, and it involved a Black teacher. Our school had classes for gifted students, but most of the kids were in the regular classes, and I was one of them. I remember in fifth grade the teacher looked at us and said we were going to grow up to be hoodlums. I’ll never forget that. To get that kind of message from somebody who was trying to help you grow and develop was striking. I still remember her tone and the way she looked at us. It was clear that we weren't valued even though there were students at the school who were. When racism comes early, it definitely leaves a mark on you. It's one of those things that you take note of, that you don't forget. It was especially memorable because it's an early signal of your worth to the world. And there's a weight that comes with that. It’s a hard thing to process and navigate.”

Dean, Chicago Medical School; FDA vaccine advisory committee member

“I was born and grew up in India. When I was a very young child, my paternal grandmother would call me by a name that was the equivalent of the n-word in India. If you translated it, it would be ‘darkie’—that kind of a term. I was a child, so it didn't mean much to me. But as I grew older, I realized the significance of her calling me by that name. To her, I think it was sort of a term of endearment, which is really crazy to think about right, but that's how family would refer to me.

I realized that although people viewed my skin color and my gender as being a negative thing, I could do a lot of good in this world. And that's what I’ve strived to do throughout my life. If one were to take anything away from my story, it is the fact that we have ability—with the support of friends and family and colleagues and mentors—to overcome prejudices and still be able to be as successful, like I have been.”

Climate scientist

“Going to a school for Native Hawaiians, as well as growing up with my tight knit family, sheltered me from the extremes of racial discrimination as a child. But I always felt different. Our community, even though we live in Hawaii, is predominantly non-Hawaiian and there's been a large influx of folks from outside of state, as well as rapid development and catering to tourism. So I just always had that feeling that I was an outsider.

When I got older and started to pursue science as a career, I faced more experiences of racial discrimination as a Native Hawaiian female scientist. Even within the community, there are some instances where we're still not fully aware of the successes of our people and may weigh the word of a white scientist over mine—just because of what I look like and what I represent. Where we start the playing field isn't always equal.”

Pediatrician; California Surgeon General

“I was the super nerdy kid that loved learning. I had so many wonderful teachers, but when I was in the 5th grade, I was doing accelerated math with an assistant teacher who would do this pull-aside class. At the beginning of the year, she told me not to do any homework—it was like she didn’t want to be bothered. But when it came time for the parent-teacher conference, she told my mom, ‘Nadine has not handed in any homework for the entire year.’ When we walked out of the classroom, I looked at my mom and explained, ‘Mom she told me I didn’t have to hand in the homework.’ I thought my mom was going to be mad, but she turned to me and said, ‘I know. It’s called racism.’

Just the idea of knowing as a child that an adult thinks you’re worthless, that is a terrible feeling. It can cause you to question your value. So to girls of color who have had a similar experience: Don’t let anyone take away your worth. You are valuable, you are precious—even when the world tries to tell you otherwise."

Educators and Community Leaders

President, Tennessee State University; International President, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority

“When I was in elementary school in Memphis, the fire department let my friend’s house burn down on my street because the discriminatory policies of the day didn't allow them to come to a Black neighborhood. They said it was because it was outside the city limits. But we were very close to the department, and if you see a fire burning, and you're a fireman…

The racial climate would not allow African Americans to participate in any of the water, fire, or sewer systems. So when I saw that happen, it had a profound effect on me. The next day, my father led a march downtown to make sure we could get fire protection in our neighborhood. It was successful, and we did get it. That’s what sparked my activism and my advocacy to fight for social justice. Even now as president of Tennessee State University, I push students to become involved. I teach them about social justice and the importance of education as our most significant intangible. I tell my students: You are valued. Believe in yourself.”

Minnesota Teacher of the Year 2020

“I was raised in Atlanta, Georgia with my mother and uncle, who were very firm about me loving my culture and ethnicity as a Somali American. I knew to be proud of who I was. But when my family moved to Ohio in 2000, that all changed because the demographics changed. One particular experience after school, I was tasked with finding plastic utensils and plates for the pizza our student leadership group ordered. I went to the supply closet to gather those things, and when I walked in, there was a white lady there. When I started reaching for the items, she stopped me and told me I needed to stop taking things. She said, ‘You people always take things. And you destroy things, too.’

As a 14-year-old hearing her anger, the violence in her tone shook me. That’s just one of many experiences where I thought my very existence was a problem, even if I hadn’t spoken or done anything. Now, as a teacher, I have students who come into my classroom and have never been told that their Blackness is beautiful or that their hijab makes their outfit pop. So I intentionally do a lot of community building with my students, especially at the beginning of the school year to affirm their identities and have them understand what a healthy racial identity is.”

ACLU National Board President; civil rights attorney; professor

“I grew up in Connecticut as a child of Jamaican immigrants. My first memory of racism was when my family moved from Hartford to a working class suburb because my parents wanted to give us a better life. We were one of only three Black families in the neighborhood and were clearly not wanted. I remember leaving the house to go to school one day and finding that ‘KKK’ had been spray painted on our house and car. I ran to tell my parents what happened. I was just 9 or 10-years-old, and they had to explain what it meant. After that I was terrified to be in our house, and I was heartbroken for my parents. They worked so hard to create safety and opportunity for our family.

I figured out very early on that I wanted to fight against the racism that my parents had to navigate every day of their lives. The trauma that comes from racism—accumulated over days, over weeks, over years, and over decades—is something we can't ignore.”

Urban agriculturalist; Co-founder & CEO, Urban Growers Collective

“In second grade, I remember getting on the school bus and being called a n****r, being told ‘Look at you with your ugly rope head’ because I had big, thick braids. My best friend at the time, Elaine, stood up and yelled at them all. She's still somebody who I love dearly, because she had the courage to protect me.

In third or fourth grade, I also have a memory of my dad running into the house panicked and full of mud. I found out that he was in the field farming, and the neighbors were shooting at him. When my mom called the police, they said they were just ‘shooting at some black birds out back.’ Those are really raw childhood memories. It's evil to me, and it has to be addressed, because sometimes people want to get rid of you.

The work I do now is about feeding people. It's about creating space to heal, and for folks to be able to release that and not internalize it, because it’s poison.”

United States Air Force, Thunderbirds

“I come from very humble beginnings in Douglasville, Georgia. In elementary school, my mom actually found a summer vacation Bible school at a church, and she signed up my two brothers and I. On the first day of the program, I saw a girl I was sitting next to on the bus, so I went up to her to say hi, but she took off. What she didn't know is that I'm a little track star; I love running. So I chased her down and asked if I could be her friend. She said no, ‘I don’t want to be friends with Black girls.’

My mom had told me before that there are going to be people who don't like you because of your skin. Don't let that upset you. I knew this was what my mom was talking about, and I couldn’t worry about things that I can't control. Instead I should focus my energy on things I can change, being confident in who I am and what I bring to the table, and making sure that I'm an advocate for those who feel like they don't have a voice.”

Founder, Therapy for Latinx; mental health advocate; entrepreneur

“One year my parents bought my brother and me snowboarding classes. We didn't have a lot of money, so to be able to go to something like that...it was a big deal.

I remember being scared because snowboarding was difficult, and I wasn’t able to do it well at first. The instructor was an older white man, and I remember once when I fell on my butt really hard, he said: 'What are you stupid? You guys come here, and you can't even learn the language in this country.' I was in so much shock that an adult would talk to me that way. I kept feeling like I must have done something wrong. I never told my family about that until I was an adult.

What's interesting is that as a kid I felt I was in the wrong, and I didn’t realize this person was being racist towards me until my early 20s. I internalized it for years. It's hard to let it go. The biggest thing is to not blame yourself.”

Oldest active U.S. National Park Ranger

“I was in a drama class, and I was reading the part of Mariamne from Winterset, a Maxwell Anderson play. When I finished, the teacher asked me to please remain after class; I assumed she wanted to congratulate me because the reading had been so fine. She pointed out I was reading the part against a boy named Eddie—who was white. She said, ‘You know, we can't let you do that…the parents would never allow that.’ I went out in the hallway and cried. I still remember it, and I am 99.”

Managing Director, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility at Missouri Historical Society

“When I was 18, there was a CVS in my college town where my friends and I shopped all the time. We came to realize that one of the cashiers would not wait on us. We’d stand in line and she wouldn’t be available, but when a white person came, all of a sudden she was. At first we thought, that can't be what's happening. But when we started speaking to other student of color organizations on campus, they knew exactly what and who we were talking about.

The local CVS manager wouldn’t do anything, so we ultimately wrote a letter and elevated it to the flagship CVS, and they let her go. It was one of the first times I realized that it didn't matter what school I went to, or how I was dressed. Just because of the color of my skin, people could choose to ignore me. It was a big wake up call, because prior to that, all of my experiences were in predominantly Black communities.”

Teacher; nail artist; entrepreneur

“When I was in third grade, we were visiting family in Atlanta. There was a gaggle of us walking through the mall—I was the youngest—and I will never forget as we walked by another group of similarly aged people of white backgrounds, I heard two people yell the word ‘ch*nk.’ Everything went blank. It was such a harsh reality to hear the word in reference to myself. As I walked away, they kept saying it, and one of my older boy cousins finally turned around and confronted the group. They got into a fight.

It was traumatic. After that, I really tried to assimilate myself and negate my Asian culture, just so that I could not feel that again. Now looking back at it, I think, ‘Why didn’t I just embrace it?’ Now, the rise of K-pop and Korean culture has definitely helped. Seeing people like me in pop culture and media—even now as a full grown mom and adult—has impacted my sense of how I view myself. Everyone says it over and over again, but representation really does matter."

Businesswomen and Entrepreneurs

Chief Accounting Officer at Reputation.com; Board member, Silicon Valley Community Foundation

“I was 5 years old and my family lived down the street from my elementary school in Arlington, Virginia. When I’d come home from school, our neighbor, Otis watched me. He was an older gentleman who didn't speak English fluently. I’d read the newspaper to him. One day I came home and told Otis and my parents that I couldn’t read. At first they laughed it off but after a week or two, they're like, ‘Wait a minute, why is she saying this?’ My mother was substitute teaching at my school and when she walked past my class, all the Black kids were at a table coloring, and all the white kids were in circle time reading with the teacher. My parents went to the principal and made a really big stink. The next thing I knew, I could read again.

My parents were constantly supporting me, saying: ‘You can do this. You can read.’ If you have somebody saying that in your ear, especially as a little kid, you're gonna believe it.”

Co-founder, The Hollingsworth Cannabis Company; entrepreneur

“I was born and raised in Seattle, Washington and was at the fair located just south of Seattle. I'm on this ride, and apparently my feet weren't where I was supposed to have them. I didn't know, I'm a 10-year-old kid. I heard them yell, ‘Hey, Blackie. Hey, Blackie.’ I didn't respond because I had no idea what that meant. Finally, the ride director said, ‘Hey, Black girl. Put your feet against the freaking wall.’ I didn’t say anything, but when we got in the car to go home I asked my mom, ‘What does Blackie mean?’ I saw she was angry, so I knew that was not a good word to call someone of color.

It wasn’t until my 20s that I started to process what happened. Beforehand, being Black sometimes felt like a disadvantage, but now I’m so glad I'm Black. I love everything about our culture. It's given me more sense of pride and an appreciation of how resilient our people are. When I think about owning our cannabis farm, it was built on the dream of our grandmother and ancestors.”

Disabilities advocate, President & CEO of Easterseals