What Gun Violence Researchers Would Study If Congress Would Fund Their Efforts

In the wake of the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, and continued activism related to gun control, businesses and political groups alike have turned toward active steps they can take to diminish the threat of gun violence. Dick’s Sporting Goods and Walmart restricted sales to minors, while President Donald Trump and the Justice Department tried to ban bump stocks, the firearms accessory used in the Las Vegas massacre last October.

But the people who study gun violence say these are not proven approaches at reducing the phenomenon. Instead, they would like to see evidence-backed gun policies that are demonstrated to work before they’re passed into law or become corporate policy.

There’s just one problem: That body of research doesn’t exist yet. Because of the 1996 Dickey Amendment, which effectively strangled the field by depriving it of federal funding, there’s only a handful of researchers exploring the most important political issue of 2018.

While large-scale, multi-year studies are expensive, Dr. Mark Rosenberg, the former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Control and Prevention, believes that in addition to the self-evident benefits of saving American lives, funding gun violence, ownership and rights research are also beneficial from a purely fiscal perspective.

“The federal government estimates that the value of a single human life is between $7 and $10 million,” Rosenberg said.

“Let’s say your results save 10 lives. That’s a minimal effect. You’ve saved $70 million. And that’s just the monetary cost. For every person who is killed, you destroy a family and damage a community.”

To that effect, HuffPost spoke with experts in the field about what they’d like to study if they had the funding, and how much it would cost to make those dreams a reality.

1. Establish a gun violence victims health registry.

There are many gaps in our collective knowledge about gun violence in America, which results in 11,000 homicides, 22,000 suicides and tens of thousands of non-fatal shootings each year. The epidemic is also a financial drain, with some estimates putting the cost of America’s gun violence epidemic at more than $100 billion. Still, without more data, that’s a ballpark figure.

We know even less about about the toll gun violence takes on individuals and communities, such as the long-term consequences of being shot and the burden of mental illness among the injured and their communities.

For Dr. Sandro Galea, an epidemiologist and dean at the Boston University School of Public Health, establishing a registry that enrolls and follows the victims of gun violence to assess the long-term consequences of gun injuries on individuals and their communities ― similar to the World Trade Center Health Registry, which tracks the health effects of 9/11 ― would be a “dream project.”

In Galea’s estimation, the registry would cost between $5 million and $10 million per year for about two decades.

“That would give us a better scope of the burden of disease,” he explained.

2. Study kids who witness routine gun violence.

People who live in low-income and minority neighborhoods are disproportionately affected by violent crime, including gun violence.

Dr. Nina Agrawal, a pediatrician who practice in New York City’s South Bronx, sees the effect gun violence has on her patients firsthand.

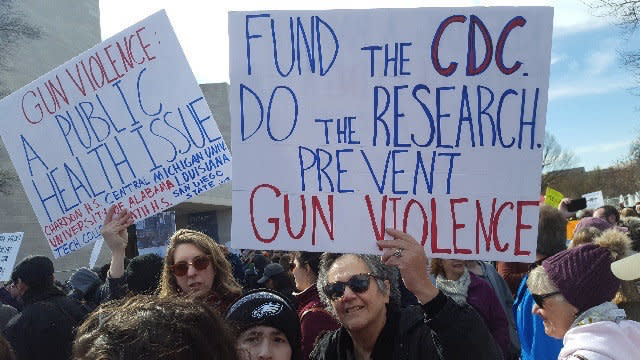

Agrawal and her colleagues participated in the national March for Our Lives on March 24, and she said the speeches she heard children give during the event reflected what she hears from her patients.

“In the South Bronx, my patients are shot on the streets, not in their homes,” she said. “Pediatricians often are not comfortable asking about guns and providing gun safety education, even though gun violence is the third leading cause of death in children.”

“It results in emotional trauma and doesn’t get recognition.”

With more funding, Agrawal would want to identify the number of kids who witness gun violence, who hear gunshots, who have family members who have died and who don’t feel safe coming home from school.

3. Study what lawful ― and illegal ― gun ownership look like.

As it stands, we don’t have a clear picture of who gun owners are and how they differ from non-gun owners.

Dr. Matthew Miller, a professor of health sciences and epidemiology at Northeastern University, would fund a large-scale study of gun owners and their families, and compare those individuals to non-gun owners and their families.

“We should learn how often people who are lawful owners of firearms today become unlawful owners tomorrow, and what predicts the transition,” Miller said. Armed with that data, politicians could develop licensing stands that reflect the likelihood that someone will transition from a legal to an illegal gun owner.

As it stands, our licensing laws are based on dogma, not science, and they differ from state to state, meaning that our federal licensing standards are about as strong as our most freewheeling state’s rules. States with loose laws are also in the majority. As of 2016, 25 states had ‘F’ gun law ratings from the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

Beyond licensing, Miller wants to study red flag and domestic violence orders, as well as interventions to reduce the gun suicide risk for vulnerable kids and adults.

“By interventions, I’m not talking about forced confiscation of guns, but rather efforts to change social norms so that people act in their own interest,” Miller said.

He added that he wanted people to understand risks guns impose and to be able to protect themselves and their families.

4. Investigate what safe gun storage looks like.

Both Agrawal and Miller saw value in learning more about how to help gun owners store their weapons as safely as possible. Although many gun owners keep weapons in the home for protection, the reality is that having a firearm in the home raises the risk that the occupant will be the victim of homicide, suicide or an accident with a gun.

Agrawal would like to investigate how effective the ASK campaign is, which encourages pediatricians to ask caregivers if there is a gun in the home where their child plays.

Miller, who published a study last month about parents who leave their guns unlocked even if their child has a condition that puts them at risk for suicide, wants to push his research further.

Qualitative and quantitative studies could help us better understand how to talk about the risks of owning a firearm, he explained, especially when that gun is stored unlocked or loaded ― or both ― or when someone in the home is going through a tough time, or has a mental illness, substance abuse, anger problems or children.

“And that’s just for starters,” Miller said of his hypothetical research plans.

5. Make more gun violence research centers a reality.

Dr. Garen Wintemute launched a gun violence research center at University of California, Davis last summer and now he wants five more, with budgets of $2 million per year for five years, renewable on a competitive basis.

Additional centers would allow investigators to study gun violence on the state level, and the resulting research could later inform state-specific policy solutions, he said. Compared to decentralized projects, research centers concentrate decades of expertise under one roof, which enhances the overall quality of what the group produces. “Magic happens around the table,” Wintemute explained.

Before he launched the UC Firearm Violence Prevention Research Center, Wintemute, a professor of emergency medicine who has researched gun violence for more than three decades, donated more than $1 million of his own money to keep his research going after federal funding dried up in the wake of the Dickey Amendment.

Beyond opening additional centers, Wintemute would want to see 20 large-scale research and evaluation projects in place at any given time, which he estimates would cost $500,000 to $1 million per year and would last for three to five years, as well as 50 smaller projects, clocking in around $100 million to $250 million per year for two or three years.

As a veteran gun violence researcher, Wintemute knows how important it is to have a pipeline of young investigators moving into the field, and he’d like to see money go toward supporting investigators who want to transition into gun violence research, as well as new investigators, postdoctoral scholars, doctoral students and graduate students.

“As capacity and the qualified labor force grow, funding should grow as well, ” he said.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.