One Woman’s Story of Surviving Domestic Violence as an Undocumented Immigrant

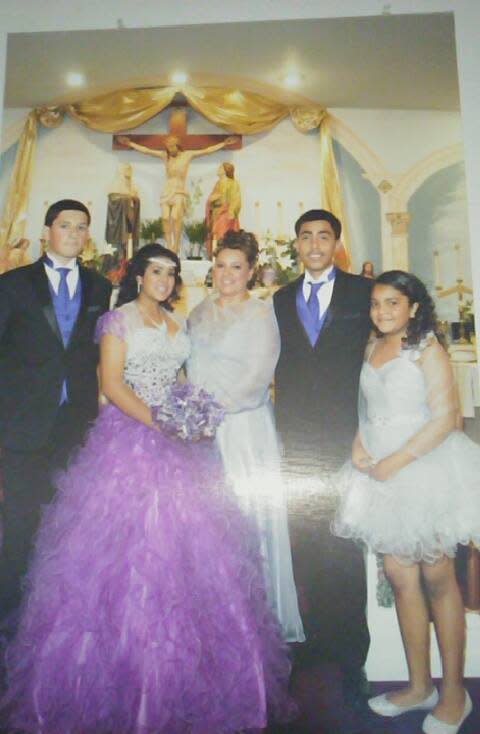

Blasa, with her family, hopes her own daughters grow up feeling empowered. (Photo courtesy Blasa Oyoque)

Blasa Oyoque has been in the United States for over thirteen years. She came from Mexico to be with the father of her children; twice she crossed the border without documentation. The first time she tried to cross, she was in the back of a car with one of her children by her side, their bodies barely covered by a thin piece of cloth. After some time in the United States, she ultimately went back to Mexico to be with her parents. But her desire to have her children with their father, all together as one family, led her to once again seek to immigrate without documentation. The second time she was by herself, in the back of a van, again covered up.

But Blasa Oyoque isn’t just an undocumented immigrant. She is also a mother, an entrepreneur, and a survivor of domestic violence.

Oyoque met the father of her children in Mexico. She said when they were living in Mexico, they had what she considered to be a normal relationship. He had manipulative tendencies, but when he decided to cross the border to the United States, she ultimately followed. It was then that the man she had risked so much to be with became even more manipulative and controlling. While he would go out every night with his friends, alone, he banned Blasca from having any friends of her own, from leaving the house, from learning to drive, to going to work.

Related: SAFE Act Introduced to Protect Domestic Violence Survivors in the Workplace

Speaking through a translator, Oyoque told Yahoo Health that it was, to date, the most isolating time in her life.

And then her partner started using drugs. At first he hid it, she said, to keep the children from finding out. But eventually he stopped caring. He would openly not only use drugs, but womanize. Then, when Oyokue was seven months pregnant, he started to beat her more intensely. Which is when Oyokue decided she had to leave, for the safety of not only herself, but both her children and the child still unborn she was carrying.

When she separated from her partner, her family in Mexico criticized Oyokue for her decision, and to this day they still tell her that she should get back together with him for the “sake of the children.”

Oyokue says that when she first met her now former partner, he was already starting to become physically abusive, but it times the behavior would ebb. She was fearful. She stayed. But as his behavior escalated she knew she had to leave him. After the time when he beat her while she was pregnant, she called the police to report the incident. He was put in jail – but only three months after she reported him the first time.

When he had been jailed, Oyokue’s former partner thought it had been for a rape charge. He learned only later that it was for the domestic violence charges filed by Oyokue.

Related: 16 Poignant Photos Show What A Domestic Violence Shelter Really Looks Like

But despite his jail time, Oyokue’s partner still had not been deported. She says he became afraid of her, though, as she threatened to call the police if he ever came near her or her children again. He evaded deportation for another six years before a minor traffic stop eventually forced him out of the country for good as a result of newer, stiffer penalties for domestic violence perpetrators.

(Photo courtesy Blasa Oyoque)

When Oyokue left her partner, before he even served his jail time, she again dealt with extreme isolation. Being a stay at home mom, she says, had been so isolating – and even more so given the way her partner prevented her from having any real contact with the outside world. Simply to try to meet people, Oyokue would take her children for long walks, up and down the streets of their city. She learned to drive so she could start working and providing for her children.

In trying to support her family, now as a single mother, Oyokue worried about deportation herself. She knew her prospects for employment were limited since she did not have a social security number and did not want to threaten her family’s living status in their adopted country. So she started her own business, making tamales. She survived, she says, by making and serving tamales. Oyokue grew her tamale business, eventually getting into catering as well. During this time she also sold Avon.

“I became an entrepreneur,” she says, knowing she would do whatever it was she had to do to earn an honest living and support her family. To this day, she still works two jobs.

(Photo courtesy Blasa Oyoque)

Oyokue also found herself lucky to become involved with an organization for domestic violence survivors. It was through this organization that she was informed that she could apply for a visa because she had been a domestic violence survivor. She immediately began the process and now, eight years later, is in the midst of the final paperwork for securing her green card.

She says that at the time of her abuse, she didn’t worry about the consequences of being deported because of her immigration status. The only thing on her mind at the time was surviving the abuse, protecting her children, and seeing justice served. “I wanted him punished,” she says of her abuser. “What he did was not right. I wanted to protect my unborn child.”

She credits the domestic violence organization with changing her life but helping her begin the process of becoming legalized. “They helped me go to the next level,” she says.

And most rewarding, she says, was that the organization offered her an opportunity to help other women, women who were starting out from where she had once been. She became motivated, she says, to keep these women coming in for the support available to them, to receive more information regarding domestic violence issues. Oyokue herself started giving presentations to other undocumented survivors of domestic violence, assembling power points and other visuals, doing whatever she could to encourage women like her to become empowered. Oyokue says she was not only grateful for the opportunity to learn so much herself, but to help engage so many other women.

One of Oyokue’s primary focuses now is working with women who don’t know that their domestic violence status can lead them to be legalized. “It took me so long because I didn’t know,” she says.

“Empowering others is something I enjoy,” she shares, noting that the women she works with often come in “feeling inferior, hopeless. They don’t know where to start. They don’t know why they continue in the situation they are in. I tell them that they have learn to love themselves first, value themselves. If they don’t feel like they are worth something and they don’t love themselves, they’re always going to be under the hood of machismo. I empower other to be unafraid to report their abuses.”

(Photo courtesy Blasa Oyoque)

Oyokue says she hopes her own two daughters grow up to love and respect themselves and that they learn early on how to be in control of their own lives and not be manipulated by others as a result of not having the power to love and respect themselves.

Her daughters participate in the Cuidate program through the Responsible Sex Education Program of Planned Parenthood of Southern Nevada. Translating as “Take Care of Yourself” in Spanish, Cuidate is a small-group, culturally-based intervention program to reduce HIV and sexual risk behaviors among Latino youth utilizing videos, music, role playing, and interactive games to help Latino youth learn about safer sex practices and how best to negotiate those practices for themselves. Oyokue says her daughters actively recruit friends from their community to come to the Cuidate programs – and to then engage and train others themselves.

Oyokue herself is also a Promotora de le Salud Reproductive with Planned Parenthood of Southern Nevada, or promoters of reproductive heatlh. Oyokue holds “platicas,” or dialogues, in her home for other Spanish-speaking women to come and be amongst peers, to talk about the reproductive and sexual health issues – including domestic violence – and to gain the resources and tools they need to themselves educate their friends, neighbors, and community about the services available to them through Planned Parenthood. Oyokue herself often gives presentations to other women on a variety of sexual and reproductive health topics for her community.

“Blasca always opens her door,” says Rosita Castillo, the Program Manager for the Promotres de Salud and Cuidate of Planned Parenthood of Southern Nevada. “She has a poster on her wall” with promotores information and an award she received for her participation in the program proudly displayed on her wall, Castillo says.

(Photo courtesy Blasa Oyoque)

After she receives her green card, Oyokue looks forward to returning to Mexico and seeing her family there – especially now that, because of all the support and knowledge she has since acquired since leaving her abuser, she is no longer afraid of the father of her children. She says her children respect her and support her because they have seen how hard she works to survive. She dreams of someday having a newer car, buying a house, and seeing her children go to college.

Oyokue says the message she would like to give to all people suffering from domestic violence is not to be afraid. “Don’t be afraid to report. Don’t be afraid to look for help. Seek help. And love yourself.”