Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon and the greatest movies never made

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Quentin Tarantino declared years ago that he was planning to retire after a 10th and final film. What that film will be is newly in doubt, following the announcement that he has scrapped a script called The Movie Critic, even though it was scheduled to shoot within months.

Here’s what little we know about the story. With Taxi-Driver-esque overtones, it was to have followed a lonely, somewhat unhinged second-string film reviewer writing for a fictitious porn magazine in the late 1970s. A 16-year-old Tarantino, who was inspired by a similar person in real life, might have been a minor character.

Rumours had it that certain iconic scenes from 1970s cinema (such as the Paul-Schrader-scripted Rolling Thunder) were to have been remade for it, and also that a host of stars from earlier Tarantino joints – perhaps even playing their earlier characters – would have appeared in a kind of “goodbye metaverse” send-off. John Travolta, Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie and Jamie Foxx were all names floated.

Tarantino had led us to expect, not a career-capping epic – which he feels he already achieved with Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood – but “more of an epilogue”. Why he axed this film, in the absence of any statement from him, has been a matter of rabid speculation online. He has said before that “most directors’ last films are f–king lousy”, and perhaps the pressure of going out on top sent him back to the drawing board. He has dispensed with plenty of other scripts in the past.

Whatever his rationale, changing his mind about The Movie Critic means that it gets a brand new plaque in the hall of fame for unmade films – the ones that might have been great, but came unstuck for a host of reasons before they got in front of cameras. Here are a fateful eight of the other most infamous examples.

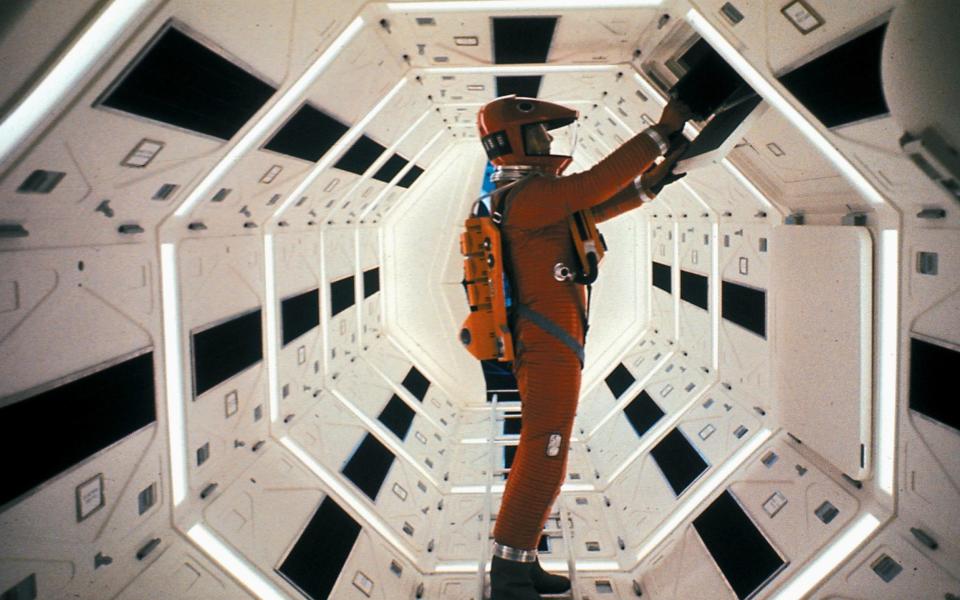

1. Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon

In September 1968, several hundred books about Napoleon Bonaparte were shipped from Paris to the London office of Stanley Kubrick. He set about ransacking them for research material with typically obsessive fervour. 2001: A Space Odyssey had just come out and this was to be next; he planned the film – “an epic poem of action” – with a strategic bravura worthy of Boney himself. As he worked on draft after draft of the screenplay, he toyed with David Hemmings or Oskar Werner for the leading role, but eventually settled on Jack Nicholson as his preferred choice.

Several factors scuppered the film. In 1970, Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo came out, and was a demoralising box office flop. Kubrick tried to revive his Napoleon later in the decade, but the economics of the time became inimical: enormous inflation rates meant the necessary budget for a three-hour battle epic was too risky for any American studio. It would haunt Kubrick for years as the film that got away, and he probably wouldn’t have been consoled by Ridley Scott managing to get his surprisingly jocose version off the ground.

2. Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune

A half-century before Denis Villeneuve and a decade before David Lynch, a surrealist’s far-out take on Dune came tantalisingly close to fruition. Jodorowsky, an underground god for his head-trips El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973), somehow persuaded a consortium of French producers that his vision for it could be achieved, despite a script Frank Herbert saw (“It was the size of a phone book”) which would have lasted at least 11 hours on screen and cost $15m.

For Jodorowsky, Salvador Dalí alone demanded $100,000 per hour to play the Emperor of the Known Universe, Shaddam IV, alongside Orson Welles as “floating fatman” Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha, and a generally insane international cast: Gloria Swanson, Alain Delon, Hervé Villechaize, Udo Kier, Geraldine Chaplin, David Carradine. Jodorowsky’s own 12-year-old son Brontis would play Paul Atreides.

Impressively, around $10m was raised, with $2m spent in pre-production on creature designs by Moebius, sets by HR Giger, special effects by Dark Star’s Dan O’Bannon, and music by Pink Floyd. The documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013) retells this quixotic saga, which ate up years of many talented lives, before that budgetary shortfall snuffed it out.

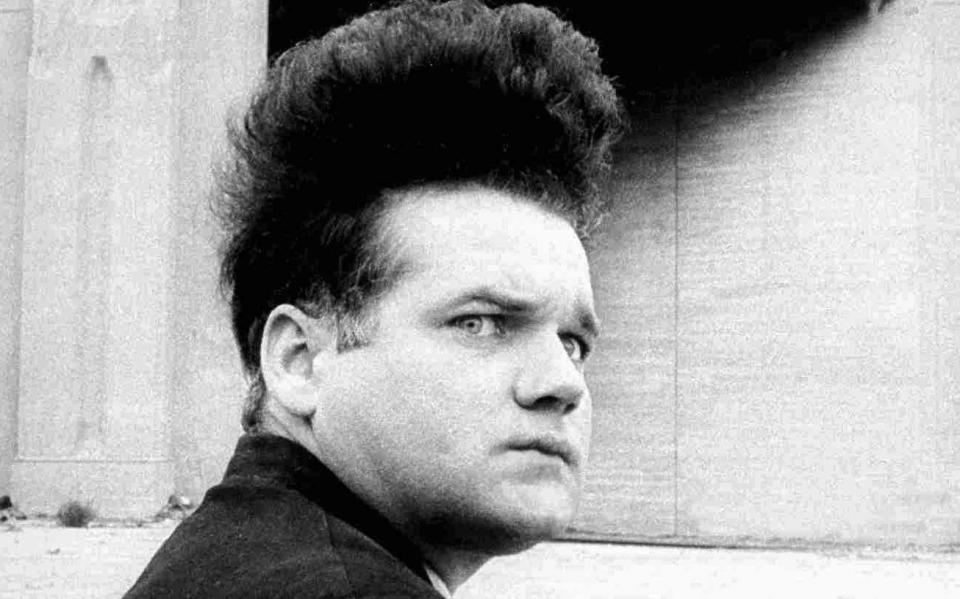

3. Orson Welles’s Heart of Darkness

In 1939, the 24-year-old Orson Welles had proved a great deal already, coming off his feted staging of Julius Caesar and radio production of The War of the Worlds. He presented RKO Pictures, then one of Hollywood’s big five studios, with a 174-page script derived from Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella, which he intended to be his first feature.

Welles would play Marlow almost entirely in voiceover, because the camera was meant to represent the character’s gaze from beginning to end, with a total of 165 first-person panning shots meticulously described in the script. He even considered playing Colonel Kurtz as well, to underline his statement about the duality of man.

It wasn’t just the $1m budget, for an untried filmmaker, that gave RKO pause. Welles’s intent to revolutionise film aesthetics plainly scared them; the theme of lust for power made the moguls uneasy; and the script’s stance against fascism made it a hot potato, with international relations on a knife-edge. Welles abandoned it, and embarked on Plan B: Citizen Kane.

4. Ken Russell’s Dracula

At some point between Tommy (1975) and Altered States (1980), Russell wrote his treatment of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. As you might expect, a dutiful prestige literary piece it was not. He transposed the plot from the 1890s to the 1920s, made Lucy an opera diva, and imagined the Count as a debauched, personality-swapping aesthete. (He would later accuse Francis Ford Coppola of plagiarising ideas for his 1992 version.)

Actors thought to have been in the frame include Peter O’Toole or Oliver Reed as the Count; Peter Ustinov as Van Helsing; Mia Farrow as Lucy; Sarah Miles as Mina, and Michael York as Jonathan Harker. Most head-spinningly of all – Mick Fleetwood, in an unknown role. “If you lived for centuries,” Russell wrote, “would you go weak in the knees at a picture of a dull clerk’s fiancée and lock yourself away in a gloomy castle? I wouldn’t. I’ve come up with a reason why Dracula would want to live forever.” Alas, when Universal’s 1979 Frank Langella version went into production, it drove a stake through this one.

5. Robert Bresson’s La Genèse (Genesis)

The Book of Genesis: The Movie? The redoubtable French auteur Robert Bresson, following a string of high masterpieces, nearly got this very idea off the ground in 1963, with Dino De Laurentiis agreeing to produce it. Bresson planned to take us from the creation of the universe to the building of the Tower of Babel. He even did some test shoots – but the Noah’s Ark sequence proved a major headache.

De Laurentiis had hired dozens of paired wild animals, but they couldn’t be persuaded to act nearly as well as the donkey would in Bresson’s Au hasard, Balthazar (1966). The director’s solution – “One will see only their footprints in the sand” – did not fill his producer with confidence, and the project capsized.

Much later, Bresson tried unsuccessfully to revive it in the mid-1980s, when it would have been his final film. “I want to do it so badly,” he told the critic Michel Ciment in 1983. “I’ll rush at it the way one rushes into the ocean.”

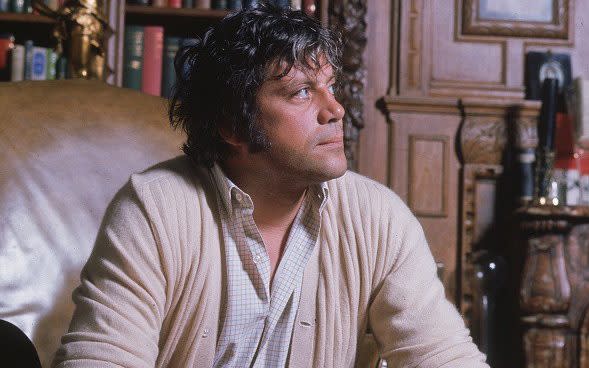

6. David Lynch’s Ronnie Rocket

Eraserhead (1977) swivelled heads on the underground circuit and made the prospect of Lynch’s follow-up very exciting. He immediately had one in mind: Ronnie Rocket, subtitled The Absurd Mystery of the Strange Forces of Existence. It involved a detective trying to enter a second dimension while standing on one leg, while being stalked by electricity-wielding “Donut Men”; there was also the side plot of a teenage dwarf called Ronald d’Arte, who has to be plugged into the mains to survive.

Beyond these characters, the film’s realm would be one of smokestacks, sparks and oil slicks, while the script, according to one précis, contained “idealised 1950s culture, industrial design, midgets, and physical deformity” – practically a blueprint, then, for every Lynch film that followed.

The problem, as usual, was budgetary: Lynch needed to step up into the big leagues with The Elephant Man (1980) and his very own Dune (1984) before he could secure that kind of money; and several potential backers went bankrupt along the way. By the time he scouted Northern England for locations, modernisation had wrecked all the industrial landmarks he needed. “Cheap storm windows and graffiti have ruined the world for Ronnie Rocket,” he explained in 2013. The film remains in a state of indefinite hibernation.

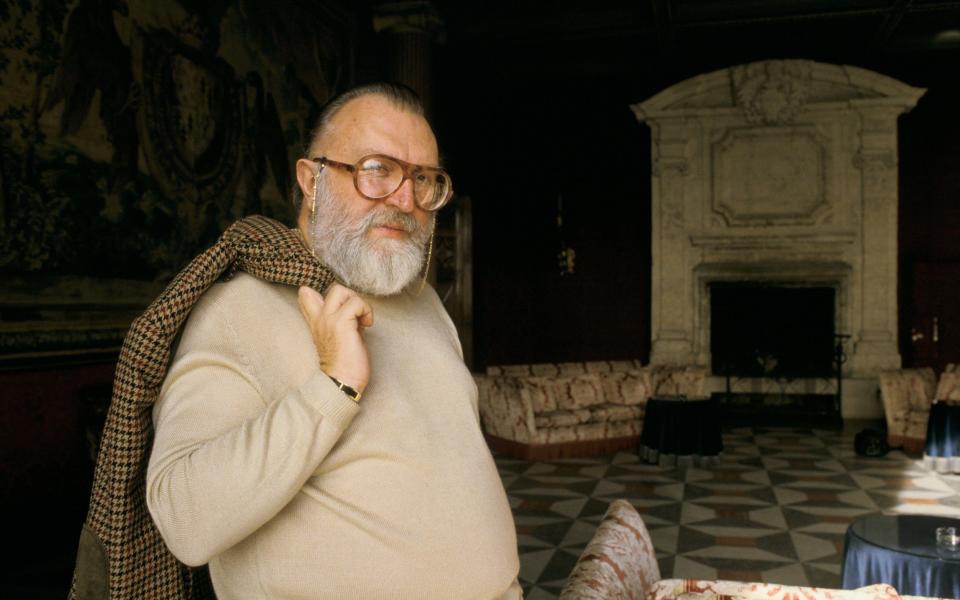

7. Sergio Leone’s Leningrad: The 900 Days

As Leone often described it, puffing on cigars, his final film would have started with a close-up on the hands of Dmitri Shostakovich at the piano, groping for the notes of his seventh symphony, the Leningrad. We’re in the summer of 1941, when he wrote the first three movements in the thick of the city’s 900-day siege.

In the most elaborate – and expensive – single shot to be conceived at the time, Leone’s camera, with the music’s sweeping crescendo, would pull back through the composer’s open window, and take us down through the “gaping wound” of the city at dawn: past queues of starving Russians, corpses, abandoned funerals, floggings of captured German soldiers, tramways criss-crossing through a suburb, and lorries on a bumpy ride to the trenches, out to a steppe, where a legion of 1,000 Black Panzer tanks lay in wait for an order to fire.

The trouble was, though Leone claimed he would be casting Robert De Niro as a trapped American newsreel photographer, this was news to De Niro, and no complete script ever materialised beyond the notion of how to begin it. While the director succeeded in raising $15m of theoretical Russian funding, he never got moving with it before dying in 1989.

8. Guillermo del Toro’s At the Mountains of Madness

This century’s most famous unmade film is probably del Toro’s long-harboured adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s best-known novel. This tale of an Antarctic voyage that veers off-course into the maw of a lost alien civilisation could hardly be more in tune with all del Toro’s nightmarish obsessions. As with almost all the films on this list, trace elements of this project pop up in many of the director’s other films, before and after he ever-so-nearly got it made.

It was ready to shoot in June 2011, with Tom Cruise in the leading role of a scrambling explorer and James Cameron producing. The sticking point was how horrific all the tentacled encounters would be: Universal were unwilling to stump up for the film’s $150 budget if del Toro was bent on delivering something with a commercially dicey R rating. They tried to talk him down to PG-13, but he couldn’t do that to Lovecraft. And so, the production cratered. Del Toro didn’t give up on the author, though, and recently managed to adapt two of his short stories for the Netflix anthology show, Cabinet of Curiosities.