“Stereophonic” duo David Adjmi and Will Butler break down writing a behind-the-scenes drama about 1970s rock stars

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"I wanted it to feel more like a documentary, so that we are getting whatever we are privy to in the fly-on-the-wall experience of watching the play," says playwright David Adjmi.

It's all happening — Stereophonic is making the jump to Broadway.

The play, which premiered last fall at Playwrights Horizons to critical acclaim and opens April 19 at the Golden Theatre on Broadway, follows a fictional 1970s rock band on the cusp of superstardom as they struggle through recording their new album. Written by David Adjmi, the play also features original music by Arcade Fire's Will Butler. But don't call it a musical. It's a play with songs.

"It's not a musical because the music isn't being used to forward the narrative of the story, and it's all diegetic music," explains Adjmi. "They do sing, but they're not breaking the fourth wall. There was a version where I thought maybe I would do that, maybe it would be A Chorus Line when they're in the recording booth and each person would have their moment. But I didn't end up doing that."

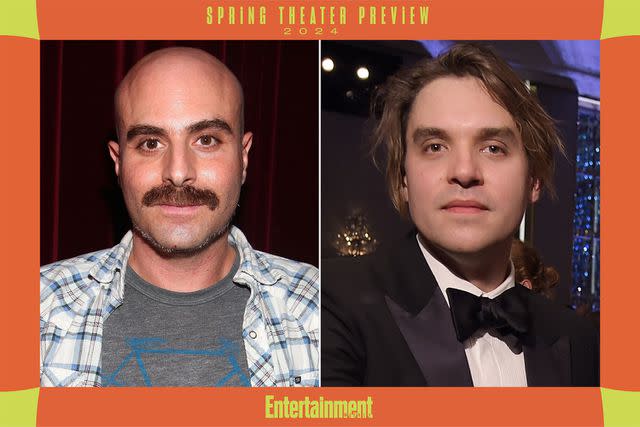

Astrid Stawiarz/Getty; Michael Loccisano/Getty

David Adjmi; Will Butler"But the music is used in a very unusual way," he continues. "I wanted it to feel more like a documentary so that we are getting whatever we are privy to in the fly-on-the-wall experience of watching the play. That's what we see. The same way you would see people rehearsing something in a documentary."

Butler and Adjmi have been collaborating on the play since 2014, exchanging snippets of the play and pieces of songs as they built their work together. "I had had enough of a structure to know where the songs could fit," says Adjmi. "It was incredibly architectonic, and it was almost like doing math problems, figuring out where these songs could go and when they could return in a different iteration. I knew I wanted to do something where I would show the development of songs, not just have a performance of a lovely song."

With that in mind, Adjmi and Butler shared a selection from the Stereophonic script, the scene that opens the second half of the play at the top of Act 3. "It's a great example of how the mundaneness of process in this play actually belies a whole host of neurotic neuroses and submerged conflicts and interpersonal dynamics," says Adjmi, as to why he chose this scene. "This is a tinderbox scene in the play because the stuff that is submerged is actually now coming up to the surface. Everyone is so exhausted; they've been there months longer than they thought they were going to be there. And people are starting to fray a little bit."

Let's take a look.

David Adjmi

David Adjmi

(1) Be sure to wear flowers in your hair

This scene opens with Diana (Sarah Pidgeon) attempting to lay down her vocals for the song "East of Eden," which Butler wrote. "I feel like these characters have maybe seen the movie or they're James Dean fans," says Butler of the title. "They're just like, 'Eden, that's so f--ing evocative. But it's more about the Garden of Eden than about John Steinbeck. 'East of Eden' is just a phrase that sticks in your brain."

Butler also wanted to use the song's title and lyrics to hint at the complicated gender dynamics between Diana and Peter (Tom Pecinka), as well as elements of their upbringing. "This scene is also very gendered," he adds. "There is a very 'Adam and Eve working by the sweat of their brows, and their children are going to kill each other' energy. It's very biblical. Diana went to church growing up, and she knows the story of the Garden of Eden, and she knows that James Dean was in the movie East of Eden."

One of the specific lyrics references wearing "flowers in my hair," and Butler purposely included that to evoke iconic imagery of flower power culture, drawing a line between who Diana and Peter were when they first met and where they are now. "They talk about how they used to be hippies, and she was sewing stars and moons on his jeans," Butler says. "There's a scene where [Holly] talks about how she idolized Diane and Peter in this time. Now, in this scene, you're seeing what it's like to be grown-ups trying to make something real, and how you have to hurt each other. It has this undertone where it's very loss of innocence, but also making all of humanity."

(2) Slashes

Adjmi writes with overlapping dialogue, denoted by double slashes on the page. "In some ways, this whole play is a musical because it's all scored out on the page," he quips. "The way that I write, it's almost like an architectural blueprint. I've always done it because I've always loved the sound of very precise, overlapping dialogue, and I want them exact. With this particular play, I wanted it to be like a Robert Altman film, so that it had that quality of spontaneity and sounded totally extemporaneous."

This script is even more complicated, given that the page is split in half to separate the scenes happening in the recording booth and those at the sound board. "Half of the page has to be the control room, which is where the engineers hang out, and that's in front of the glass, and then the sound room is behind the glass," explains Adjmi. "Diana is in the sound room in the scene, and they're in the control room. It doesn't read like Arthur Miller, let's put it that way."

(3) Eat the mic

In this scene, sound engineer Grover (Eli Gelb) asks Diana to get closer to the microphone. Butler explains what that does sonically, "Depending on the microphone, the closer you get, the more base frequencies you get out of the voice," he says. "Basically, you get a richer sound the closer you are to the microphone and the farther away you get, it gets more naturalistic. But if you get up close, then you can take out some of the low end and you have the full richness to play with. David picked it up from an engineer, but it is a real thing where microphone distance catches the emotion in a different way."

Butler also wants to be sure audiences know that the show is mic'd with the actual microphones the band would have used in the 1970s. It was an intensive process to figure out what would translate through theater speakers to give them the sound they wanted. "We would audition different microphones," he explains. "Psychologically, it was a trip because you want it to sound like the studio, but you're in a theater space with a big theater reverb and you want it to fill the space. How do you do that is a technical thing, and it affects the composition. This is the era where sound is the composition. You're composing in electrons etched onto a tape. That's your oil paint —electrons on a tape. And then how those electrons come out of the speakers is the composition, more than notes on the page."

David Adjmi

(4) No do-overs

Grover suggests that they all get some sleep and return to the song the next day, but Peter is adamant that they won't revisit anything. "He knows that she can hit the note," says Adjmi of Peter's reluctance to start over the next day. "Peter is exhausted in the scene, and he's not behaving totally rationally. He wants the album done, he wants to be efficient, and he thinks she can do it. If she can't do it, let's find a solution right now. That's the mindset that he's in. Also, this process has been going on for so damn long, and they are all a bit afraid at this point. No one is thinking terribly clearly."

(5) Pass the Courvoisier

It wouldn't be a 1970s rock story without plenty of drugs and booze — and here, we see Diana reaching for a bottle of Courvoisier to help coat her throat as she struggles to lay down her track. "I got that specifically from watching documentaries about people in rock bands in the seventies," says Adjmi. "I know that Kanye West and rappers really were into Courvoisier, but they had been drinking it at least since the '70s."

Butler adds that any singer who cares for their voice would never use such a tactic now. "Everyone now is a goddamn hippie," he says. "Alcohol dries out your vocal cords, and even lemon is not that good for you. You can put honey in your tea if you want. But room temperature water is really the best."

(6) Finding the key

When Peter asks Diana if she wants to change the key, it might seem like he's trying to be helpful, but it's actually an extremely hostile move. "This is perceived as something hardcore to say," says Adjmi. "That's an insult. 'Let's change so that you don't have to sing in this key.' That's considered really bad form. But the profession is not just note-hitter. You need to summon something from the collective human unconscious that will speak to the rest of humanity for all time, no big deal."

(7) This is me trying

Diana admits that she's struggling as she keeps trying to hit this note in the scene. Before digging into the emotional subtext of this scene, there's the objective challenge of writing a song that will allow an actor to strain for a note in a way that will play realistically. "How do we make it so it's believable that she can't hit this note?" asks Butler. "How is she messing it up in a realistic way and what is she forgetting to do and what is Peter catching that she's forgetting to do? It is like a math problem. We were tweaking the vocal melody well into rehearsals to be like, 'What's the gap where it feels like she can't hit it or she's a little too drunk or a little too tired or isn't breathing in the right way to hit it? And then what releases that?'"

While Butler tried to solve for his musical X-factor here, Adjmi wanted the song and Diana's struggles in the booth to convey something deeper about her relationships. "She's on a ledge in the scene," the playwright adds. "She's drowning in this booth. Diana is in a very troubled relationship with someone she adores, who is also a very demanding producer and somebody she relies upon to help make her songs as good as they can be. But she also feels oppressed by that. So, she is in the crosshairs of all these very contradictory emotions."

"All of her psychological patterns — that we all have in relationships when we become desperate or we feel insecure — are activated by the situation that she's in," continues Adjmi. "It's a professional situation, but it's also a personal situation because her boyfriend is out there producing this and making demands of her. And the more that he demands, the worse it gets. There is a genuine, very deep and profound love between these two people. But there is something about the dynamic of being an artist and becoming famous that doesn't work. She knows it, so she has hit this peak of contradictions in herself. There's something that she has to do in order to hit this note, and she's not getting out of the booth until she does it. But you'll have to come see the play."

David Adjmi

(8) Not enough tape

In addition to the interpersonal drama between Peter and Diana simmering under the surface, there's also the challenge of recording to physical tape — and the possibility of running out. "I was trying to figure out ways of increasing the tension in the scene," says Adjmi. "What would make it more urgent? And our sound designer, was like, 'Well, if they're running out of tracks.' That was an actual anthropological detail — the materiality of tape and what could happen to it and how it can get warped or you can ruin the low end or we run out of it. That was a very real thing that we don't have to deal with at all right now because everything's digital. I really liked calling attention to that stuff because it feels historical. Now, my stomach hurts when I watch this scene, it's so tense."

Related content:

Read the original article on Entertainment Weekly.