Sexism, Feminism, and the Movement: Kathleen Hanna Doesn’t Hold Back in New Memoir

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

More from Spin:

There is a scene in the 1995 “The Getaway, Almost” episode of Roseanne where the titular character and her sister Jackie pick up a hitchhiker who turns out to be a riot grrrl. She plays them Bikini Kill’s “Don’t Need You” and once Roseanne and Jackie hear the message behind the jarring music, they start a conversation about sexism, feminism, and the movement. Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna writes about this episode in her much-anticipated memoir, Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk, which hits bookshelves on May 14. Hanna drags the episode for its errors, but, the fact that a top-rated mainstream network series spent much of its episode spotlighting what Hanna and her fellow riot grrls were doing is significant.

In fact, everything Hanna has done as an artist is significant. This becomes even more apparent in the context of Rebel Girl. That’s not to say that Hanna is blowing her own horn in the memoir, quite the opposite. She tells her story, from a very early age, with brutal honesty. She speaks frankly and unapologetically about dealing with abuse—including emotional from her father, and, to a certain degree, from her mother—censorship, being silenced, being shut out, being a stripper on the evenings where she wasn’t performing with Bikini Kill. Hanna pulls no punches when she tells the unequivocal truth about being raped—more than once—and being on the receiving end of Courtney Love’s fist. Her accounts of her time with Kurt Cobain are poignant and heartbreaking. Hanna was the one who came up with “Smells like Teen Spirit” when she went on a drunken spray painting spree with Cobain and sprayed “Kurt smells like Teen Spirit” in reference to her trip to the drugstore earlier that day, spotting the deodorant and wondering, “What does teen spirit smell like?

Hanna had already revealed quite a lot in the 2013 documentary, The Punk Singer: A Film About Kathleen Hanna, which traced a speedy trajectory of her life leading to her battles with late stage Lyme disease. In it we see her in various stages of illness, Beastie Boys’ Adam Horovitz, the model husband, at her side, administering medication and providing endless support. Rebel Girl pushes the reveal much further with in-depth detail about not only Hanna’s illness, but also her and Horovitz’s love affair-turned-happy marriage and their adopted son, Julius.

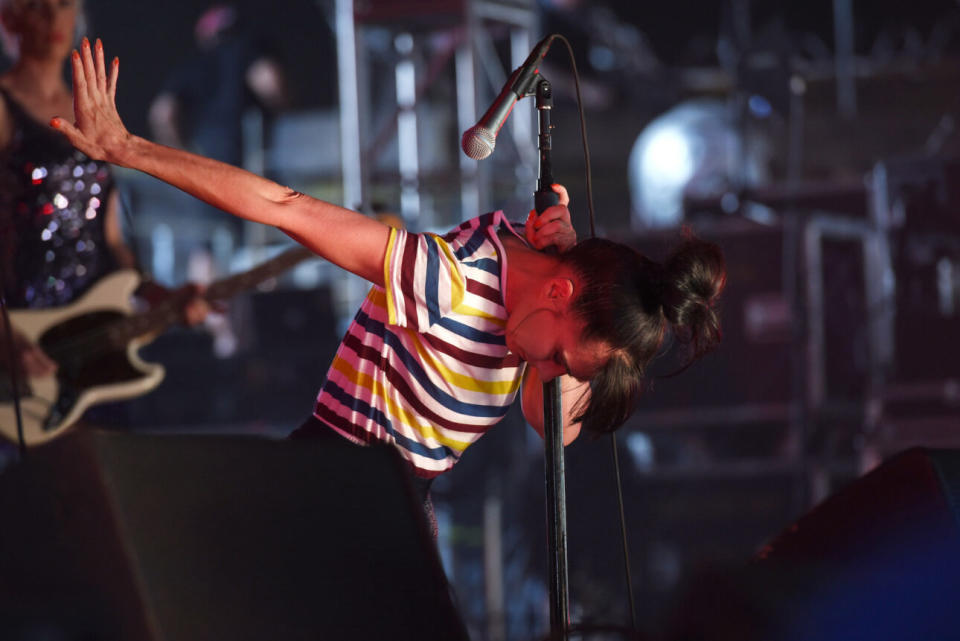

Rebel Girl is thorough, including piecing together Hanna’s organic moves from Bikini Kill to Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin. With the “fourth wave” of feminism in full effect, the time is more than right for Hanna to take to the stage, both with Bikini Kill, whose international tour begins June 1 and to talk about Rebel Girl. Hanna’s book tour kicks off on Rebel Girl’s publish date in Brooklyn, New York at Greenlight Bookstore. Joining Hanna on the book tour will be a slew of celebrity hosts including Molly Ringwald and Amy Poehler.

One week ahead of the book tour, Hanna speaks to SPIN about the trauma that resurfaced when writing Rebel Girl and how it continues during the promotional cycle of the book. To quote Hanna, “There’s no HR in punk rock.”

Writing this book must have been very difficult.

KATHLEEN HANNA: Yeah, it was horrible. It sucked. I learned a lot by going through what I went through writing the book. I came out the other side feeling a huge weight lifted off my shoulders. There is a silver lining, but at the same time, it was absolutely hideous to revisit some of this stuff and find out I hadn’t processed a lot of it. I wasn’t able to write about it and not process it. I took months off at a time and went to therapy. The good thing [the book] did was I found a trauma therapist and started dealing with that stuff. I’m not walking around in fight or flight every day in my life anymore.

You revealed a lot in The Punk Singer, but you went so much further in Rebel Girl. What gave you the courage to do that?

I’m older. I moved from New York to California. I was going to be near my mom which gave me a lot of confidence. My mom always gives me unconditional love and support and having her near makes everything easier for me. I felt like I was walking around with this hideous slug trail of stories that I needed to just get rid of and excise. Because I was leaving New York, I wanted to leave a lot of the ‘90s and early 2000s, leave them with the boxes I got rid of. It was really important to me that my new lifestyle be one that allows for happiness, where I’m not constantly being triggered and retraumatized all the time. I want to be a good parent to my son. I want to have really happy, lovely times with him.

When the things that you love bring you so much pain—whether that be a family which is supposed to be a place of security and safety, but all you find within that is pain, or being on stage and you find so much pain there as well—it can make you afraid of feeling happy because you think the next thing that’s going to happen is it’s going to get ripped away from you. Through the process of the book, I wanted to come to terms with the crappy things in my life and the joyous things in my life and be able to move on from them. The way I can move on is by facing them head on.

The whole time you were an internationally recognized figure, releasing records, touring, you still had a day job. Was that because of not wanting to compromise your ideals?

Having jobs made me more appreciative of time off. I wanted to do something with it because the jobs were terrible. They were sucking the life out of me. As soon as I could get back on stage or get back to writing music, I felt like, “I don’t want to waste my valuable time. I don’t have time to fuck around.” I think it cut through some bullshit I didn’t care about. It sucked to not have any money, but, back then, it was so different because I lived in a small town. In Olympia, you used to be able to get a room in a house for $100. I was very happy with my lifestyle. I could go to Target. I could go to the thrift store and buy almost anything I wanted. I could get groceries for myself. There were lean times where I was waiting for my next check, but I don’t look back on it as depressing. There was definite frustration when I saw people working not as hard as me who had it made or had generational wealth. It’s not like I never get bitter or never feel jealous. But I feel really fortunate that I came of age as a musician in Olympia, Washington.

You eventually did sign to a major label then had less money than you had when you were an independent artist.

It was an interesting experiment. I was thinking, “Do I regret not going after the brass ring more or not being more popular?” But I have the kind of career that I want to have. Doing these interviews has brought the ‘90s back to me, and also the early 2000s. The cumulative amount of sexual harassment that I suffered at my art job, which was making music, was really extreme. It’s something I didn’t harp on too much in the book, though it was mentioned.

Let me put it this way: When I was a kid, I loved waterskiing. My grandparents in Oregon had a crappy boat from Sears on a lake in Troutdale. In the summers, I would go out there, but in order to water ski, my skeezy uncle would have to drive the boat. He would always grab my ass and make comments about me and try and get me to make out with his friends who were in their 20s and I was 12. Not a good situation. But I put up with it because I loved waterskiing. In my 12-year-old mind, I was like, ‘This is the price I pay to do the thing I love.’ I thought eventually I would get out of that cycle.

When I got on stage, and here I am in a band, and this is the thing I love to do the most, I didn’t realize it was just going to be that same skeezy uncle situation for most of my career. It’s not like that now, because we have a crew and I don’t get that treatment because I don’t see it—though I’m sure it’s still there. But I had to put up with these men dehumanizing me at every fucking venue, in some different psychotic way, every show. And then having men in the audience also be violent and scream at me every show.

One of the things I’m processing now at the ripe old age of 55 is, what do you do if the things that you love have been attached in your mind to pain? It makes you scared. I didn’t want to be a bigger name in the music business partially because I mentally couldn’t handle what I thought would just be more and more pain and more dehumanization and more objectification. So I did it as self-protection more than wanting to stay elitist or have a cult following or something like that. But I was happy with what I had in the small world I had. As somebody who wanted to be a community builder, even having a niche amount of fame had real detriment to it. I’m still grappling with that stuff. I’m not like “Oh, I came out the other side and I’m totally happy and everything’s great.” In doing these interviews, I’ve had to be like, “Wow, I never processed any of that. I just went to the next show.”

In the book there are inflammatory stories about, among others, Steve Albini and Courtney Love. Was there any concern about naming names?

You do the crime, you do the time. I don’t want to hurt either of those people. I don’t want either of them to be targeted in any negative way because of the things I wrote. I hold no ill will towards either of them. But this is the truth of my story. I’m sure I could show up in people’s stories in a really toxic, negative way as well and more power to them. Steve Albini wrote a really amazing article about independent labels versus major labels. I thought it was a well written, important article, almost a canonical text for people who are involved in underground music. I could still really enjoy that and get a lot out of it even though I had not such a great experience. I’m sure he’s changed his ways since then, but I was writing about my experience in the ‘90s, and my experience in the ‘90s was, he was in a band called Rapeman and told me to my face it was based on a superhero who raped women. Somebody thinking that was okay was horrifying to me. And that experience was a typical experience being in the punk scene in the ‘90s. It can still be a typical experience for a lot of people today.

I definitely had to take stuff out for legal reasons, but it wasn’t anything super substantial. It’s a fact that Steve Albini was in a band called Rapeman. It’s a fact that I was physically assaulted by Courtney Love at Lollapalooza. It’s well documented. There are court papers to prove it. People who’ve stepped into my life and been toxic, I don’t care what they think of me. I’m more worried about how my mom is going to handle it when she reads the book. I care more about the people around me feeling okay about it.

Speaking of people around you, Ad-Rock [Adam Horovitz] comes across as the husband of the century.

He’s really awesome. But you know what? All men should be as awesome as he is. It shouldn’t be remarkable. My friends are like, “He so loves you and he’s so supportive. It makes me want more out of my relationship when I see the way he is around you.” I’m just like, “But you should have that. Everybody should have that.” Also, he can be a douchebag, let’s be honest, as can I. We both have our moments of not being cool to each other or not our best selves. But that wasn’t something I wanted to talk about in the book. You’ve got to keep some things personal.

How do you feel feminism has changed over the years?

The great thing that’s changed in feminism is that it doesn’t have to be called feminism. It’s intersectional. People who truly care about the way that racism and sexism can present in a myriad of ways in people’s lives, whether it be having privilege or bearing the brunt of those things at the same time, people are more mindful of various ways that people express gender and that it’s not a binary anymore. An important thing for me to remember is that we do need to have arguments and not always agree and that arguments can be very productive and fruitful. That’s what keeps anything, whether it’s a feminist scene or a collective or a band, alive, is to have arguments and to disagree and to listen to differing viewpoints. That’s something that’s very lost in our culture. I want to have a conversation with other women in music who make different choices than I do because I can learn a lot from the conversation.

What are your thoughts about abortion becoming a political tool?

The conversation needs to be widened from just people who can get pregnant to the fact that there have been people in this country who have died of very curable illnesses, and who still die a very curable illnesses, every day, because the healthcare system is broken, and the insurance system is totally based on greed and denying people’s claims. If we’re talking about women who are dying because they’re not getting healthcare, it often needs to be talking about people who live in areas where there is no healthcare or who can’t afford insurance, and even when they can afford insurance are being denied access to healthcare. They’re just using abortion as an issue and they are not thinking, “People are actually going to die from this.” They’re thinking, “This is our political issue that we can use as a crowbar to stack the Supreme Court,” and do millions of other really horrible things like erase reality-based history books from schools and allow trans or nonbinary kids to get beat up or even killed at school. It’s absolutely despicable. We can’t just focus on clickbait articles about these very specific situations. I feel like we need to look at it as a larger issue of the death of democracy and the rise of totalitarianism, and what are we going to do about it. A lot of us feel—especially with the Supreme Court being what it is—really hopeless and helpless. And again, that’s really triggering. If you’ve ever been sexually assaulted, you definitely know what feeling helpless and hopeless is. Welcome back to the terrordome.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.