What Do Your Rooms Say About You? The Answer Might Be a Surprise

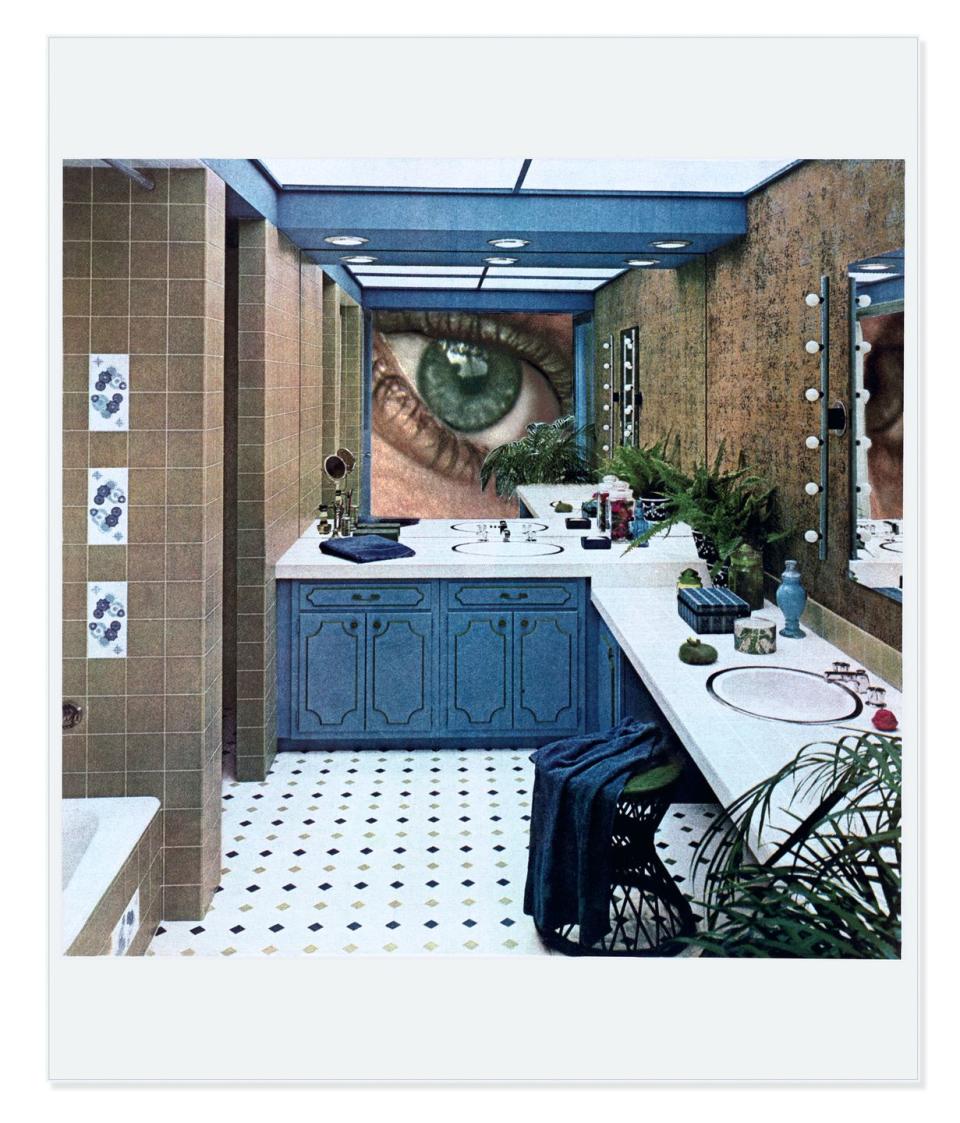

Above: Nakeya Brown’s Assimilation Blues (2016), from the photographer’s “Mass Production Comes Home” series.

In 1916, Henri Matisse painted The Piano Lesson, which features his young son Pierre at the family piano. Part of a seminal series of intimate portraits, the work is a visual illusion that blurs the boundaries between inside and outside. Points of entry are unclear; the assumed safety of shelter feels precarious, even slightly threatened.

The public display of our private spaces has a long history in art-making. From photographers to dancers and other creatives, many artists have attempted to engage with interiors—illuminating and recasting the banal spaces of everyday life as sites for the extraordinary. At a time when many of us are opening our homes to outsiders through the form of gridded squares and virtual gazes, the topic takes on a renewed relevance.

In Inherent Distance (2018), the conceptual photographer Elliott Jerome Brown, Jr., depicts a small kitchen. On the left, a young man bends over an opened oven door; on the right, another man, partially out of the frame and wearing a neon-orange cap, keeps a hand tucked in his pocket. Between them is a white door bisected by a dark wooden bar that suggests both a gap and a point of connection. The work encourages the viewer to revel in the potential of the unknown—and to consider both what the bolted door is keeping out, and what it is keeping in.

Another contemporary photographer, Nakeya Brown, has created a series of still-life images as a visual commentary on the relationship between Black women and mass-produced household products. In one, a canister of Blue Magic hair conditioner rests upon a wooden stool in front of a wall covered in floral wallpaper. The jar of hair product, an iconic staple in certain households, is presented on a pedestal as something to be revered. (And if you know, you know.)

I was reminded of a performance by the late choreographer Blondell Cummings, who had collaborated with Meredith Monk, Brian Eno, and others in New York’s postmodern dance community in the 1980s. Cummings’s piece “Commitment: Two Portraits,” which included the renowned Chicken Soup (1981), subtly invoked the lineage of Black women’s labor within and beyond domestic spaces. In the piece, she fiercely scrubs the floor and gracefully handles a cast-iron skillet as though it were a feather. “Hard work has become a pleasure, a distraction, in these long solitary days,” she says. It’s a proclamation that seems eerily relevant to the current moment.

Maintaining one’s shelter from the outside world requires labor, and domestic pleasure is often best yielded by following arduous rituals. When we’re confined to our homes, and that labor and those rituals are all we have, what tensions do we unearth? In 1998, mixed-media artist Tracey Emin unveiled the first iteration of her work My Bed. The work examines Emin’s personal wreckage of depression—alcohol and juice bottles, unfolded newspapers, cigarettes, and tissues surround an unmade bed. In Emin’s telling, there is something dually alluring and devouring about a bed, especially during an imposed solitude.

Where Emin considers the bedroom, the artist Martha Rosler—whose photomontage works appropriate pop culture—heads to another space in the home. Her Bathroom Surveillance, or Vanity Eye presents a large, watchful eye inset within a picture-perfect 1960s bathroom. Recently, a friend and I talked about how the last year has forced a reckoning with our appearance through the discernment of a Zoom optic. As trivial as this may seem in an era of massive grief, we concluded that the camera is unflattering. And yet, after a lifetime of policing our own beauty, the silver lining is that we are learning to be more accepting of our raw selves in the eye of the Zoom beholder.

Though the late artist Alma Thomas began as a figurative painter, the canvases she filled from her Washington, D.C., kitchen transitioned into abstraction, often featuring her signature thick, colorful dashes. Thomas’s Celestial Fantasy (1973)—inspired by human journeys to the moon—attests to her interest in realms beyond her window. Her later works are rooted in repetition, with patterns overlaid against backgrounds that are not quite transparent. This is what the domestic gives us—an opportunity to reveal and conceal, out of a great will to survive.

Taylor Aldridge is a writer and visual arts curator at the California African American Museum.

This story originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of ELLE Decor. SUBSCRIBE

You Might Also Like