The Real Story of Supreme

From a block away, you could smell the Nag Champa in the air, like a sandalwood smoke signal. As you got closer you could hear the music echoing through the canyon of Manhattan, then see the crowd outside the building, sometimes 40 or 50 deep, spilling off the sidewalk onto Lafayette Street. The locus of it all was ostensibly a store—but back then, when it first opened, in 1994, retail concerns seemed incidental to the real purpose of Supreme, which sprung to life as a frenetic meet-up spot for the growing downtown New York skate community.

In those days Lafayette Street wasn't the commercial thoroughfare it is now, so kids from the boroughs and from New Jersey, Long Island, and upstate could gather without having to worry about being hassled by the cops or encroaching on the upscale businesses that now dot the neighborhood. At that time, there were no metal barricades or security guards, though the notorious lines of customers that would eventually necessitate such things would start soon enough. Out of sight, in an office or a back room, the man who conjured it all into being—Supreme's founder, James Jebbia—could be found working the phones, haranguing his suppliers, coaxing another drop of tees, hoodies, and caps. He was on a mission to fill his perpetually empty shelves, impervious to the notion that something grand was taking shape.

One of those who flocked to the store was the filmmaker Harmony Korine, who had moved into his first apartment, just a couple of blocks away, a few months before Supreme opened. “I never really even thought of it, in the very beginning, as a business,” he tells me. “It was more of a hangout spot. You know, a place for that specific crew.” Supreme's start coincided with the making of Korine's first film, Kids, directed by Larry Clark, which famously depicted that same crew's style and antics downtown. “It was raw,” he says of the energy that the store tapped into. “It was a specific attitude, and probably the DNA is [still] there now, but it really was a pure New York City kind of street skating.”

The appeal of Supreme was instant. Jen Brill, who today is a prominent New York creative director with close ties to the brand, was an Upper East Side high-school student in 1994, when she first started venturing to Lafayette, just to see who was working at the new skate shop. “It was the cutest boys with the best styles and the shittiest attitudes,” she says. “There was crazy energy around the store. It didn't feel like a shop. Because they definitely didn't want to sell you anything. Maybe they didn't even want you in the store.”

Brill wasn't the only one struck by what was happening downtown. Skating had for years enjoyed a gritty reputation in New York, but suddenly the cultural fringes were crashing into the mainstream. Kids was released in 1995, but so was Clueless, starring Alicia Silverstone, which depicted a fundamentally different but equally stylized kind of skate crew. That same year ESPN held the first X-Games, a mass-market spectacle that put skateboarding in the undignified company of other “extreme sports,” like street luge and sky surfing.

Twenty-five years later, as fads (like televised street luge) have fallen by the wayside, Supreme remains a skate brand—a purveyor of all the hard and soft goods one needs for the sport. But it is something much more than that, too. Since its beginning, in 1994, Supreme has slowly worked its way to the very center of culture and fashion. Or more accurately, culture and fashion have reconfigured themselves around Supreme. Supreme's clothing and accessories sell out instantly, and the brand has become a fashion-world collaborator of the highest caliber with projects now under way with designers high (Comme des Garçons, Undercover) and low (Hanes, Champion). Though the particulars of the privately held company's business are undisclosed, a $500 million investment in 2017 from the multinational private equity firm the Carlyle Group, for a 50 percent stake, put Supreme's valuation at $1 billion.

But you wouldn't necessarily know it by walking into a Supreme store today, where the music is still loud and the Nag Champa is still thick in the air. (In addition to the New York locations, there are now outposts in Los Angeles, Paris, and London, as well as six in Japan.) And you might not fully appreciate Supreme's profound sway simply by reading fashion magazines or style blogs, which rarely, if ever, feature Supreme ads or interviews with its founder. You certainly wouldn't learn of the brand's influence by shopping in malls and department stores—Supreme doesn't have any wholesale accounts, so you won't find its merchandise in those places. Loud as the clothing can be—red fur coats, leopard-print pants, “FUCK”-emblazoned denim—the brand is nearly silent, letting the clothes and the people who wear them do the talking.

James Jebbia, who, as ever, guides virtually every aspect of the company that he founded, declined to be interviewed in person for this story but agreed instead to respond to my written questions via an in-house interlocutor—and provided perhaps the deepest and most insightful articulation of his vision and design philosophy that he's yet offered on record. Jebbia's life and business remain, for the most part, a mystery to those who aren't part of his inner circle. What's clear is that he operates on his own terms and refuses to make concessions based on what anyone else wants or does.

“The reason that we do things the way we do is because we respect the customer,” he says. For Jebbia this is not a mere marketing platitude but rather a kind of guiding, almost sacred, principle. From the beginning, he studied what was happening in the streets, relying on what he observed, not on himself or another designer, to chart the brand's creative path.

“The influence was the people who were around the shop—the skaters,” Jebbia says. “They would wear cool shit; they wouldn't wear skate clothes. It would be Polo, it would be a Gucci belt, it would be Champion. We made what we really liked. And it kind of was a gradual thing. From a few tees, a few sweats, a pair of cargo pants, a backpack. But the influence was definitely the young skaters in New York. Also traveling to Japan and seeing their great style. Traveling to London. It was a combination of that. I never really looked at it as ‘This is what a skate brand must make.’ ”

Supreme is famous for its box logo—a red rectangle with white text, inspired by the artist Barbara Kruger's text and photo-collage work—which appears every season on T-shirts, hoodies, and caps. But for years Supreme has also been making oxford shirts, chinos, selvage denim, M-65 jackets, pocket tees, and other pieces that speak to a different kind of downtown population: artists, architects, graphic designers—anyone who might otherwise be shopping at A.P.C. or Agnès B. for quiet, casual clothes that fit well and last a long time. There have been far fewer blog posts dedicated to Supreme's flannel shirts and cashmere sweaters, but all of these sensible pieces are just as fundamental to the brand as the box logo itself.

“I've always looked at it as, why shouldn't we make good stuff?” Jebbia says about exceeding the expectations of a skate brand. Supreme stores are notoriously impeccable—the T-shirts, folded with razor-sharp edges, neatly stacked; the clothes spaced just so on the racks.

Jebbia's retail mastery comes in part from his experience working at Parachute in the 1980s. The now defunct brand of futuristic fashion—worn by notable style beacons of the era such as Madonna, Michael Jackson, David Bowie, and Rip, the abhorrent drug dealer from Bret Easton Ellis's novel Less Than Zero—once had outposts in Chicago, Los Angeles, Toronto, and Bal Harbour, Florida. The shop was on Wooster Street, across from the original Comme des Garçons boutique, which had opened in 1983, the year Jebbia arrived in the States from Sussex, England, when he was 19.

Six years later, in 1989, Jebbia opened the foundational streetwear boutique Union on Spring Street, which led him to a meeting with Shawn Stüssy. Before long, Jebbia was starting the first Stüssy store in New York, also on Wooster Street. Union and Stüssy, along with Triple 5 Soul and XLarge, made up a new kind of retail scene in SoHo, one based around a subculture, not designers. There was just one piece missing: a skate shop. “I was not thinking about it at the time,” Jebbia says. “But it was just an instinct that something was needed.”

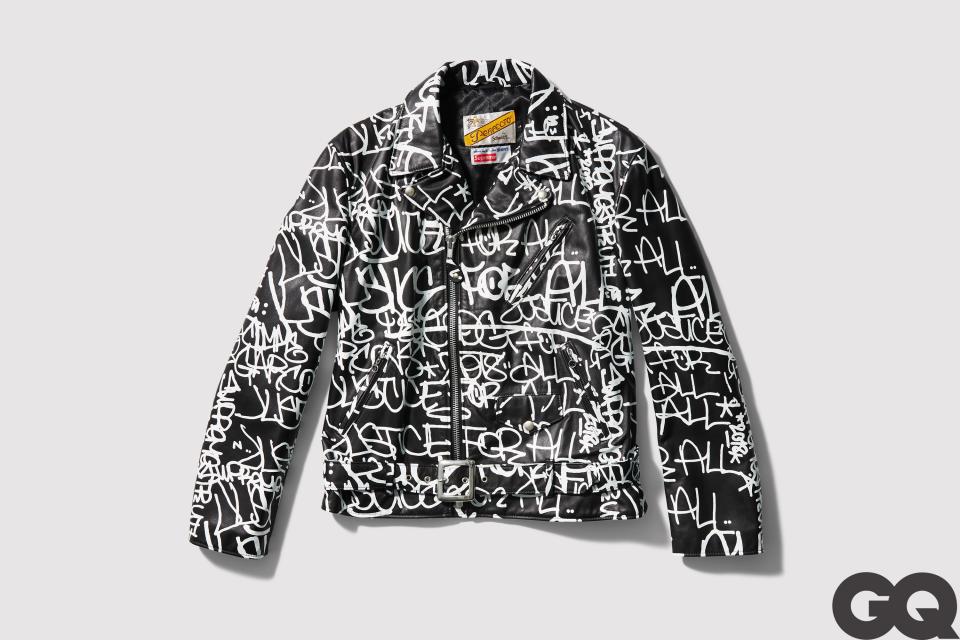

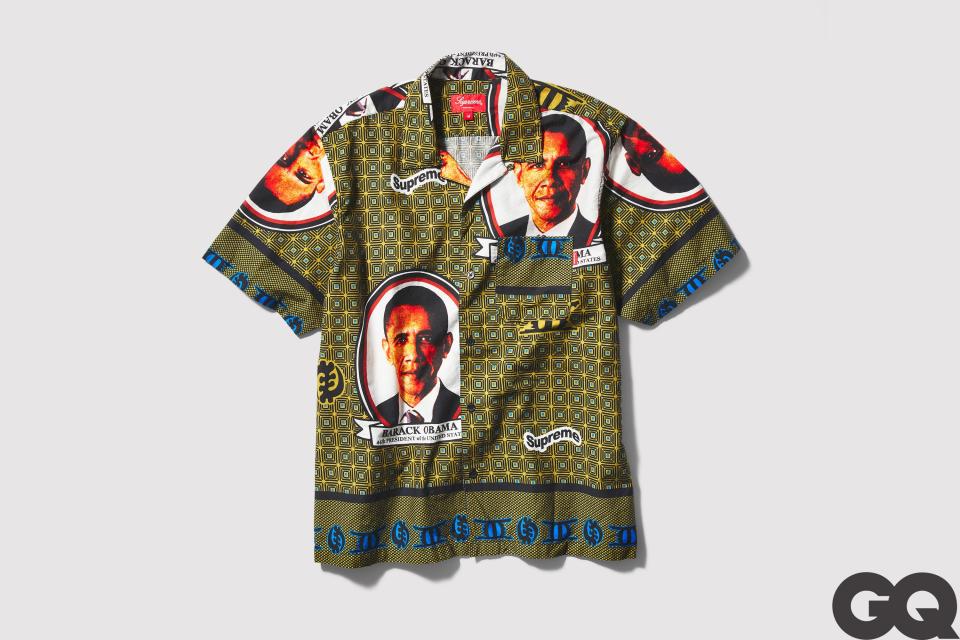

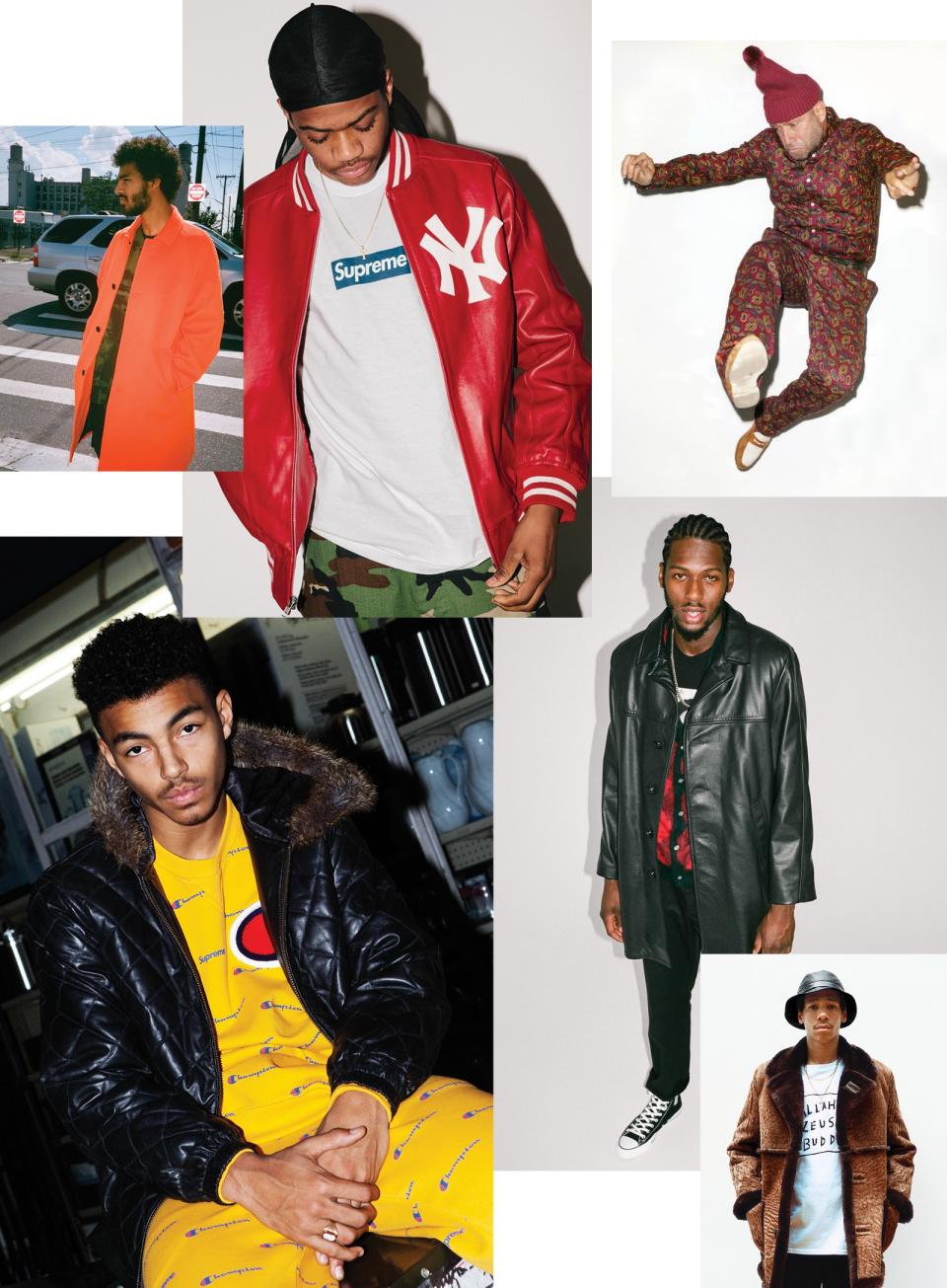

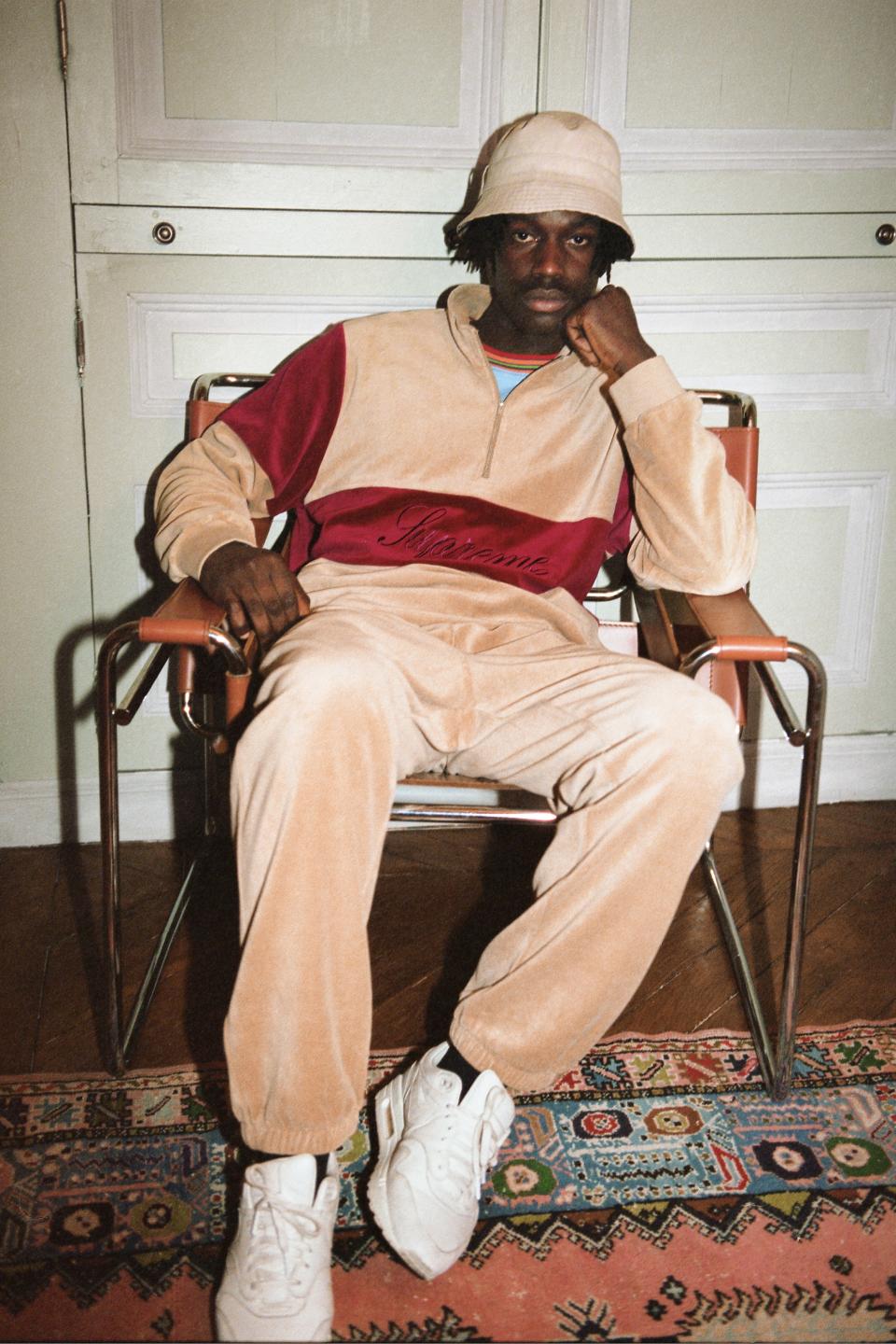

A Rare Look at the Supreme Fashion Archive

The formula for success—for building a brand that lasts for 25 years—sounds simple enough: Create a high-quality product that will last a long time, sell it for an accessible price, and make people desperately want to buy it. But executing such a plan is far trickier. And in figuring out how to thrive according to strict adherence to its own highly specific principles and logic, Supreme has, deliberately or not, re-arranged the alignment of the entire fashion industry.

“It's a fashion leader,” says Alastair McKimm, a longtime fan who has styled for the brand and was recently appointed editor in chief of i-D magazine. “The reason that it's so successful and the reason that it's so influential is the fact that it's been there, growing slowly, being very, very well managed from day one.” He says Supreme has led the charge in the new consumerism: “small collections, making things very limited, making things very exciting when you actually get your hands on them.”

Limiting quantities has become Supreme's M.O. and one of its most important innovations. It's part of why the brand has so many loyal fans—and why it has left so many hopeful shoppers frustrated and bitter. But the strategy evolved naturally out of the early days, when the shop was nearly empty. Short runs were produced out of necessity because Jebbia lacked the resources to keep a steady assortment of goods in stock. “We'd make some tees, some sweats; if they don't sell, we're going to be stuck with them,” he says. The solution was to produce less. And if something sold well, instead of manufacturing more of that thing, he'd often make something different. “It wasn't a shop full of basics, where you could get the same product month after month. What we were doing had to have some excitement to it.”

Naturally, gauging what might be successful was harder to do in an age before things like Instagram. Jebbia never knew what was going to move. Of course, just about everything did: “We'd actually have some seasons where we were sold out of the summer product at the end of March. We'd have nothing to sell in April, May, June, July. People would come in and be like, ‘This shop is shit. Why are people talking about this?’ And what are we gonna say? ‘If you'd have come in two weeks ago, it looked really good’?”

Jebbia's solution to his inventory problem was a simple, but radical, one: He found a way to replenish his supply weekly. While many shoppers now hold out until end-of-season sales to buy, Supreme has created a considerable sense of urgency that has made every Thursday—“drop day,” in the parlance of Supreme fans—a major event.

And indeed, the concept has lately proliferated. Thanks to Supreme, the “drop” has become a fashion buzzword—much like what happened with the terms “streetwear” and “collaboration.” Celine's creative director, Hedi Slimane, made news recently by reportedly planning a major business overhaul to create a “fluid delivery cycle.” Meaning: There will be drops. Balenciaga, Burberry, Moncler, and others have been using the model in hopes of adding some heat to their collaborations and limited runs. Gucci's buzzy drops come frequently and sell fast, including Supreme-esque capsule collections made in collaboration with the New York Yankees and the Spanish artist Coco Capitán. This tactic is seen as a way for big legacy brands to connect with younger shoppers. It's also a work-around for competing in a retail system upended by Supreme.

As the brand grew and began to expand—it opened its first outpost in Japan in 1996—Jebbia started thinking beyond hoodies, tees, and caps. But that doesn't mean he stopped thinking about hoodies, tees, and caps. Craig Atkinson, the CEO of CYC Designs, which owns the brands Wings & Horns and Reigning Champ, began working with Supreme around this time. Jebbia had come across some sweatshirts that the company was making and was impressed. Before long, CYC was producing almost all of the sweats Supreme was sending to market. Atkinson was struck by Jebbia's personal obsession with the sweatshirts. “He was maniacally passionate in terms of the quality, whether it's the color, or the fit, or the materials that we would develop for them,” Atkinson says. He recalls interactions sometimes getting heated. Long arguments over the particular merits of a shade of navy weren't uncommon. “James just had a very high expectation,” Atkinson says. “And I'd say he has a very high taste level as well.”

Brands like A Bathing Ape and Neighborhood—Jebbia's new neighbors in Harajuku—had already established large fan bases. He was drawing inspiration. But Japanese brands and their customers were not the only things Jebbia had his eye on in the late '90s and early '00s. “We weren't blind to Helmut Lang. We weren't blind to FUBU, either,” Jebbia says. “There was an awareness of a lot of what was going on out there, being in New York. But there wasn't as many big fashion brands then. There just wasn't. But I've got to say: Helmut Lang at that time was really important, personally.”

Atkinson recalls that Helmut Lang was the singular brand Jebbia referenced during their time working together. “He only used to wear Helmut Lang T-shirts,” he says. “He was very particular about how the collars fit him. He used that as a benchmark.”

Noah founder Brendon Babenzien put it plainly: “I think Supreme created the world that the entire [fashion] industry lives in today.”

Jebbia says that his standards for quality were based on what was already being made. “With a lot of the skate brands at the time, the quality wasn't good, the fabrics were kind of crappy,” Jebbia says. “So we had to make our product as good as the brands that kids in New York were wearing: Polo, Nautica, Carhartt, Levis.” By avoiding wholesale he could keep prices down. “Our thing,” Jebbia says, “was to try and make things as good as the best brands out there—but not the fashion brands—and have that quality that people are going to wear these items for a long, long time.”

As the ambitions grew, the operation became more sophisticated. Luke Meier, who'd been put in charge of design in 2002, supervised a growing staff that had expanded capabilities. Meier recalls that the immediacy with which his designs hit the store were huge boons for Supreme. “When you think about a tailor shop or somewhere where they're really making a product, you can sell it, like, a block away,” he says. “You feel very closely connected to who's buying it, who's wearing it, why it's cool. It's not like you're in some studio across the world.”

Meier moved on from his full-time position at Supreme in 2009 and later launched the label OAMC. In 2017 he and his wife, Lucie Meier, were named co-creative directors of Jil Sander. “Surprisingly,” he says of leaping from Supreme to a high-fashion luxury brand, “it's not so different.”

Angelo Baque, who founded the brand Awake NY, started at Supreme in 2006, back when, he says, the company was still a “mom-and-pop” operation. In the years that followed, the brand expanded rapidly, introducing new pieces like, say, the aforementioned oxford shirts and cardigans. “Twelve years later everyone is making those,” he says, “but for Supreme to make a cardigan in 2007, that was fucking revolutionary for the brand.”

For much of that period of expansion, Brendon Babenzien was in charge of design at Supreme (he has since launched his own brand, Noah). “It was really fun,” Babenzien says, “being able to indulge both the youthful side—the side that I grew up with—but also address some of the needs of our audience who had been with the brand from the beginning.” In other words, making sweaters that were as sought-after as Supreme's tees. “I had high hopes to have Supreme be able to simultaneously make really progressive things and truly classic things,” he says. “I think we accomplished that.”

Pulling off that kind of expansion, Jebbia says, required paying careful attention to Supreme's customers. “We try and evolve,” he says. “Twenty years ago, if we'd have put a fur coat out at the shop, the skaters would have stormed out. Our windows would have been smashed. Young people are a lot more open-minded today. We're trying to make things for today's youth. We're not stuck in a box.”

One undeniable result of all this growth is that in the past few years, Supreme has become massively popular. There's a very good chance that if you are not a Supreme obsessive, you have a young cousin or niece or nephew who is. There were also those who were there from the beginning, like Leonard McGurr, the artist better known as Futura, who has a pair of camo cargo pants that he bought at Supreme on Lafayette in 1995 and still wears today. Guys who never felt ripped off buying a $42 camp cap or a $110 oxford shirt, so they kept going back.

One of those guys is Andrew Rieth, now a 44-year-old geophysicist and father of five who lives near Houston and encountered Supreme back in 2001 while flipping through a skate mag. He noticed a skater wearing a Supreme hat, took interest in the brand, and called the shop. They politely told Rieth that they don't do phone orders, so he went where many people who were after Supreme in those days went: eBay. “This was before the modern-day Supreme hype,” he says. Still, caps that retailed for $28 were selling for $75. Later that year, on a trip to New York, he visited the store for the first time. “I was completely blown away when I walked in the door,” he says. “I was expecting a standard skate shop with standard skate brands. Instead they had a full line of their own clothing—super-thick hoodies, made-in-USA selvage jeans, nylon M-65s with zip-in pile linings that looked like something you would dream of finding in a surplus store. Everything had this really raw, authentic feel to it. At the same time, the thought of spending $150 on jeans or a hoodie, or $300 for a jacket, was completely foreign to me.”

Rieth walked out with just a tiger-stripe camo hat, but in the years that followed, before Supreme debuted its web shop, Rieth's collection grew. “Getting ahold of Supreme was kind of a mission.” He'd make occasional trips to New York, find pieces on eBay, and trade with friends he met through online forums. He was always impressed by the quality and design of the pieces. “The thing about Supreme, even now, is that they have always had this cool mix of military, sportswear, workwear, and vintage that you can kind of pick and choose from in a way that's tailored to your own taste. Over the years Supreme's collections have grown larger and generally louder, but I can still find things that are still low-key, tasteful, unique, and well-made.”

Since 2013, Supreme has released complete collections twice per year: fall-winter and spring-summer. These collections include everything from suits and overcoats to basketball jerseys, leather jackets, and silk shirts, as well as the famous collection of random functional accessories and sports gear (this past spring-summer a Pearl drum kit, a Super Soaker water gun, and Band-Aid bandages all brandished the Supreme logo). New collections are debuted in their entirety in advance, then divided into the weekly drops that occur every Thursday over the course of a few months. Unless there are leaks (and frequently there are), you don't know what's going to drop in any given week.

For Supreme fans, a specific thrill is derived from this system. The hottest items are decided long before they may be released. To some—to many—these pieces become essential to that season's fits. If there's a shirt in the collection that you must own, for instance, you have to check for it every Thursday until it arrives—it could be several weeks into the season—then hope you can be fast enough to buy it before it sells out.

And sell out they often do. Any Supreme regular knows that pain. But it only adds to the thrill. “Everybody feels like they're part of this underground society, you know?” says McKimm. There is a palpable awareness that you aren't the only one on the hunt.

Many Supreme pieces are designed based on reference—tweaked versions of existing pieces from the past. The truly obsessed make a hobby of digging deep into vintage archives to discover the originals, whether it's an obscure album cover that Supreme flipped into a logo, or a hard-to-find vintage military parka. But often the references aren't so hard to spot, especially for those familiar with skate and hip-hop style of the '90s. “I feel that was a golden era for clothes, for music, for art, for a lot of things,” Jebbia says.

The notion of celebrating individual style isn't specific to 1994, and it isn't specific to 2019. It's fundamental to the very act of coming of age. Which is why the youth have returned to Supreme, again and again, for three generations now. “As fashion editors and fashion directors, stylists, whatever, you're always just looking at what's happening with the new generation,” McKimm says, “and Supreme is just always right there with them.”

Since Babenzien's departure in 2015, Supreme has not named another designer or revealed any information about the structure of its creative team. Jebbia did appear, however, in 2018 at the Council of Fashion Designers of America Awards ceremony to accept the menswear prize.

“A lot of traditionalists felt like it was an unusual brand to be competing in a menswear category,” says CFDA president Steven Kolb. “I feel it was an authentic and honorable nomination, and win. And certainly spoke a lot about our industry and the direction of fashion. And also for creativity.”

Jebbia accepted the award in a gray suit, white shirt, no tie. In his succinct speech, he said: “I've never considered Supreme to be a fashion company, or myself a designer, but I appreciate the recognition for what we do.”

Fashion company or not, the moment placed Jebbia in a room with Ralph Lauren and Raf Simons and forced him to reckon with the question. I asked Babenzien for his perspective on Supreme's relationship to fashion, and he put it plainly: “I think Supreme created the world that the entire industry lives in today.”

967476984

Powerful as Supreme has become as a trendsetter, the company is still fiercely committed to its own novel approach. Supreme didn't launch a website until 2006. It was purposefully late to Instagram, too. Outside of Japanese fashion magazines and downtown NYC wheat-paste poster campaigns, Supreme's only real marketing efforts are made in the skate world. Conveniently, marketing to skaters is likely the best way for Supreme to market to the fashion world. In other words, the fact that Supreme doesn't pander to the fashion industry only makes its allure more powerful.

In terms of marketing, Supreme does have one true superpower when it comes to reaching a wider audience—one thing that it consistently executes masterfully. That is the “brand x brand” collaboration, now employed by everyone from Target and Vineyard Vines to Rick Owens and Birkenstock. Supreme did not invent the collaboration, but starting in 2002, with the first Nike x Supreme sneaker release, it proved that a big-brand partnership could be explosive in the best possible way. Since then Supreme's numerous collabs—most recently with Comme des Garçons, Louis Vuitton, and Jean Paul Gaultier—have expanded the brand's range and allowed it to dabble in a more elevated kind of fashion.

There is no science to how and when these collaborations occur. “If we could have done a thing with Louis Vuitton 25 years ago, we would have,” Jebbia says. “Or Chanel. For us, whenever we do something, it's something we feel like, for young people, this isn't already a part of their world. Or it isn't accessible to them. We could do something that opens people's minds to something they hadn't known or thought about before. Like when we worked with Lou Reed. That was just cool. What's good is good. That's really the criteria. And if it's been done, we don't do it. Simple as that.”

These collaborations succeed in two ways: They fulfill Jebbia's mission of giving kids a chance to get their hands on rare and expensive fashion for a cheaper price, and they let established fashion designers experience Supreme's unique ability to sell clothes.

“It's flattering to see that the younger generations find my fashions relevant,” Gaultier tells me. “And inspiring that the collection sold out within minutes.”

Then there is the sophisticated curation of art and culture that is integrated into the ethos of the brand, including marketing campaigns starring surprising, high-wattage celebs like Lady Gaga, Diddy, and Kermit the Frog, and editions of skate decks featuring the works of A-list art stars like Jeff Koons, Marilyn Minter, and Damien Hirst. These cultural collaborations were not the norm 20 years ago. Now few fashion brands release collections without both a celebrity-fronted campaign and an art-star collaboration.

Supreme has been credited (or derided, depending on whom you ask) extensively for bringing streetwear to the forefront of fashion, for pioneering brand collaborations, and for recruiting art superstars to put on a box logo T-shirt, but one simple thing is often overlooked: Those things only work if the clothes are good.

Supreme's Lafayette store is currently closed for renovation. The downtown shop is temporarily located nearby, on the corner of Bowery and Spring Street. The crowds outside consist of noticeably different characters than they did 25 years ago. Those milling in the lines come from all over the world, and they queue up behind metal barricades, waiting for security guards to let them in, one by one. They don't all skate, and some of them wait in line with their parents.

Of course, for anything cool, there is peril in popularity. But Supreme has so far been insulated from the dangers of selling out. This is partly because of good timing.

“In the early, mid-'90s there was always a sense of sellout culture,” Harmony Korine says. “Then all of a sudden it was obliterated. And then culture was up for grabs. It was like a bomb had dropped. There were no more rules. It was just about making things, and seeing things in a different way. And then that's when it became the most free. Then you could do collaborations with White Castle.” Supreme has worked with everyone from outsider artist Daniel Johnston to Budweiser, and never has a collaboration hurt its credibility. No other brand has been able to be as cool and as popular at once.

“The truth is, there will never be another Supreme,” says Baque. “That's why everyone is so curious about it, and that's why all the companies are trying to figure it out and they're scrambling.” Jebbia, Baque says, “is like your Phil Jackson of streetwear. He knows how to put those teams together. At the end of the day, he has the vision, and it's not about money and it's not about talent and one person; it's about having the right crew of people and finding that balance.”

Still, McKimm wonders what the limits are. “I think now it's almost at the point where it's so big, what's the future of that?” he asks. “Do you make it even more underground or exclusive, or do you let it grow and give people more access to it?”

It's the million—no, billion—dollar question, so I asked Jebbia. “We can just do what we've always done,” he says. “Which is try and be open, try and be very aware of what's going on, and try to make the best things possible for today's generation while keeping it true to ourselves. I don't have a crystal ball. But I think that we'd have to stay the course if we're not as hot. We'd do exactly the same stuff. We're in the business where that can happen—it is what it is. Many brands have been through that; some come out of it, some don't. We'd remain who we are. We wouldn't change.”

Noah Johnson is GQ's style editor.

A version of this story originally appeared in the August 2019 issue with the title "Inside Supreme."

Get it first by subscribing to GQ

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Still-life photographs by Josephine Schiele

Soft-goods stylist: Claire Tedaldi

Hair by Aja Allen using Rene Furterer Hair

Grooming by Katie Pellegrino using Revive Skincare and Dior Makeup

Originally Appeared on GQ