Phish Sphere Shows Revel in the Vegas Venue's Unreal Possibilities

Taylor Wallace

Most big live-entertainment venues weren’t built with music as the first priority. The arenas and stadiums where you can catch the biggest acts are by and large optimized for sports, not sound. In this regard, and in many other ways, Sphere—the “The” is very much not Sphere’s preferred nomenclature—is a world apart. Madison Square Garden boss James Dolan spent $2.3 billion to build this high-tech temple to audio and visual obsessiveness in Las Vegas, and after five years of construction it finally opened last September, with a U2 residency that was repeatedly extended to a total of 40 nights.

Even before you get anywhere near it, Sphere commands attention. The venue’s instantly iconic “exosphere” utilizes 580,000 square feet of LEDs to display high-definition video art and advertisements day and night. You’ll first glimpse it from afar, bulging up like a mysterious alien orb between hotels on the Strip, or reflected, glimmering, in a glass façade. “Whoa—Sphere,” you’ll find yourself acknowledging, to no one in particular. Sphere claims you can even see Sphere from space, although this may or may not be true.

Sphere is all superlatives, and it’s challenging to write about the place without getting lost in hyperbolic white noise. But it really is a one-of-a kind live-music Valhalla, and there really is no large-scale concert experience to rival it anywhere on this planet. Scoff at the hype all you want: Sooner or later an artist you really dig will announce a Sphere residency, and you’ll inevitably find yourself struggling to decide how much money you can justify spending on a night inside this marvelous thing.

The second band to headline Sphere was Phish, another institution equally unburdened by definite articles. Over the course of its 40-year career, the Vermont quartet has staked out a subculture of its own making by doing things its own way, focusing most of its energy on the live concert experience as opposed to album sales, cultivating an obsessive fan base through tireless touring and an uncompromising commitment to improvisation. Mainstream culture may have filed Phish under “jam band” long ago, but at its core the outfit is really a theatrical rock band, purveyors of psychedelia mutated by eclectic influences ranging from prog to bluegrass to barbershop, not to mention the occasional use of vacuum cleaners as wind instruments.

Phish booked just four nights at Sphere, far fewer than the market craved; face-value tickets for the Thursday-to-Sunday run sold out in nanoseconds, as did Ticketmaster's extortionary “platinum” tickets, for prices that made most responsible adults ask themselves questions like, “Christ on a cracker, is this really worth over a grand a ticket?” (Or as slightly less responsible parents might have wondered, “But when you think about it, is college still worth the investment?”)

But once you forget about the money—which is exactly what Vegas is designed to help you do—the experience is overwhelming. Imagine your favorite planetarium or IMAX theater, and multiply it by a magnitude of WTF. To put it in scientific terms, this room is ginormous, with a volume that could accommodate the Statue of Liberty—we’re talking the full-size Lady Liberty, not the compromised second draft from Planet of the Apes. The 160,000-square-foot LED screen extends all the way from the floor behind the stage, arcing up, up, up, and then, holy smokes, still further up, to 366 feet at its highest point, before curving all the way back to the last section in the rear. Look back at it from a lower level, and the 18,000-member audience seems to swell up like a giant wave of humanity, paused just before it starts to crest.

Sphere’s LED canvas is by far the largest video screen on earth, capable of 16K ultra-high resolution. Behind the screen, out of sight but all-pervasive, are 168,000 speakers that use something called the Helmholtz Equation, which—in Sphere PR-speak—“create[s]…a new sonic technology known as ‘wave field synthesis.’” The gist: It’s a sound system that can be focused like a cannon to send each instrument, and even discrete riffs, sweeping and swirling around the vast room like invisible but palpable auditory pinballs. Gone are the slapback echoes and sludgy sound that plague most arena-rock shows; the acoustics and sound engineering are impeccable, light years beyond any other music venue of this size.

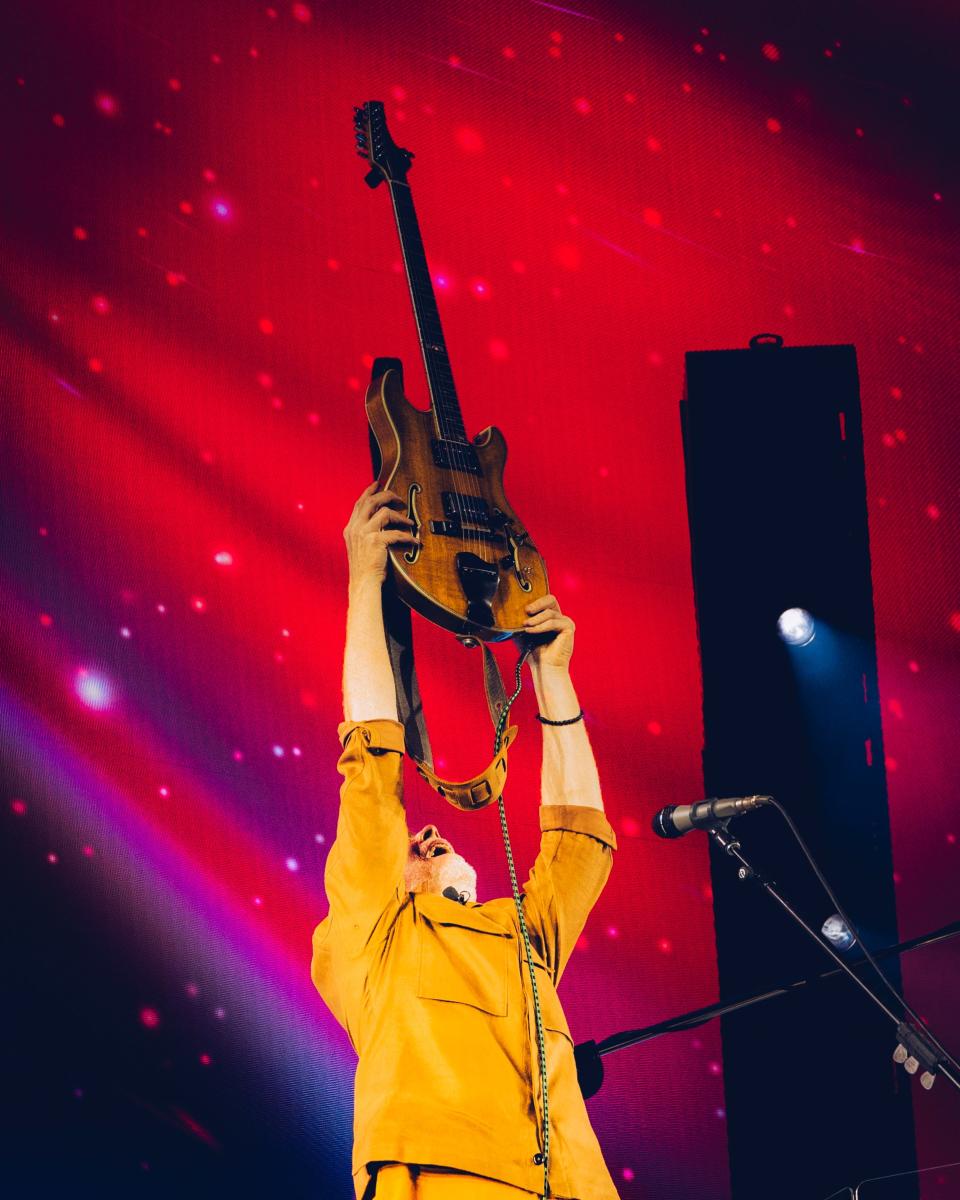

In short, even setting aside the visuals—and the seats with built-in haptics transmitting the music’s deepest vibrations directly to your spine—it’s such a perfect playground for a band like Phish that you have to wonder if Dolan has secretly been its biggest fan all along. (He’s undoubtedly a big fan of the money Phish has raked into Madison Square Garden during its 83 appearances at that venue.) The Phish mix was dialed in with an immersive clarity. Each of bassist Mike Gordon’s propulsive plucks on the Serek strings were front and center; keyboardist Page McConnell’s wide range of effects swirled and crunched throughout the room with sparkling vibrancy; and the percussive work of drummer Jon Fishman, a precise and unstoppable freak of nature behind the kit, kept everything moving like crisp clockwork. Anastasio, on guitar, was completely in command and knew exactly what to deliver in this space seemingly built for him.

Hearing this music fused with the ultra-high-def video was revelatory; Sphere can provide imagery of such clarity and at such an unreal scale that you may, like comedian Drew Carey, see the face of God.

How much would you pay to see the face of God? When Dolan sketched his idea for an ambitious new venue on a legal pad back in 2015, he said he wanted to “reinvent the live-entertainment industry.” Say what you will about Dolan, but mission fucking accomplished. Whether Sphere recoups its multibillion-dollar investment and becomes profitable will depend on the savviness of its programming and the continued existence of enough people with the disposable income to pay the eye-watering cost of admission—DINKs FTW! Sphere is either a last ludicrous monument to late-capitalist decadence or a license to print money, or maybe both. But judged solely on the merits of its engineering, interior design, acoustics, and technological innovation, it’s also an unequivocal success.

U2’s Sphere set lists were largely identical from night to night, as were the videos that unfurled across Sphere’s gigantic screen during each song. Phish’s Sphere performances were obviously a different story. Over the course of its comparatively shorter career, the band has prided itself on never performing the same set twice, and its improvisational ethos means that a song that’s over in five minutes at one show can become an epic rock odyssey that spans 45 minutes at the next (Is this still Lawn Boy? IYKYK).

So how the hell do you plan and create 12-plus hours of video art to accompany music so unpredictable? Phish’s Sphere design team, spearheaded by co-creative director Abigail Rosen Holmes (whose credits include the lighting design for the iconic Talking Heads performance captured in Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense), solved this problem by creating immersive backdrops with time and space to breathe. On the third night, during an extended “Pillow Jets,” a bioluminescent forest sprouted behind the band, glowing and expanding along with the unrelenting grooves. Later, during the anti-school rocker “Chalkdust Torture,” bands of golden star clusters filled the screens, stretching from Las Vegas to the Omega Nebula, ultimately turning green as the crowd of 18K Spherians were assimilated into the Matrix, where I write to you happily and with utmost satisfaction to report that AI is not to be feared and resistance is suboptimal.

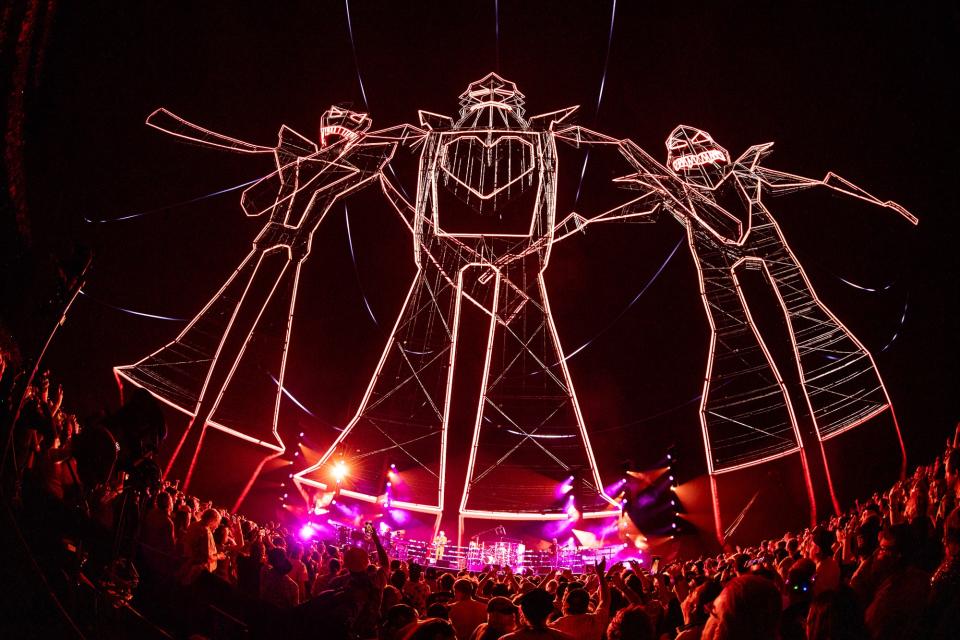

The most crowd-pleasing imagery of the run was arguably the trio of gigantic 4D robots that came to life above the stage during the final night’s performance of “Ghost.” At turns menacing and goofy, the robots grew in size and seemed to advance out into the room with unclear intentions until they were temporarily replaced by another robot with lights in its eyes that it beamed at specific sections of the audience, targeting individual groups for assimilation. Look, maybe you had to be there. (And in the words of the immortal Otto Mann, you didn’t need drugs to enjoy it—just to enhance it.)

During the ’90s, an era whose dominant rock bands mostly served their songs up with a scowl, Phish could be found bouncing giddily on trampolines, performing on the back of moving trucks, donning “musical costumes” on Halloween, performing choreographed dances to certain songs, and bowing in unison like a traveling theater troupe at the end of every act. In 1993, it performed four shows at different venues on a stage set built to resemble a giant day-glo fish tank. Fast-forward 40 years, and the act is still transporting audiences under water, only this time it's doing it in front of a vast, hyperrealistic coral reef, with undulating kelp and schools of fish swerving to the music.

During the third night’s “Fuego,” stylized video of the band members lit up in volcanic red appeared high on the screen; their images grew more fractured as the song progressed. Again, maybe you had to be there; Sphere visuals—at once high tech and firmly in the psychedelic tradition of ’60s-era Joshua Light Show projections—defy easy description. But imagine being tossed around inside a giant kaleidoscope. Or being transported into an extradimensional tesseract like Matthew McConaughey at the end of Interstellar. Those who’ve experienced ayahuasca (including anyone smoking its synthetic version during the show) may have recognized the multicolored “grid” that expanded up into the heavens during songs like “Axilla, Part II.”

Of course, they can’t all be bangers. Video of a puppy licking a camera lens in extreme close-up ad nauseum during the improvised vocal jam in the prog masterpiece “You Enjoy Myself” was funny at first, but soon wore out its welcome. Then again, what kind of monster objects to puppy kisses? And a few less-than-awe-inspiring moments did provide a necessary breather during four nights of otherwise overwhelming visual stimulus. Many in attendance chose to sit down during parts of the performance, something you rarely see at a Phish show unless there’s about to be trouble. In Sphere’s haptic seats, sitting down was almost as intense as standing up: You could tilt your head back and marvel at hundreds of multicolored pulsating bubbles seemingly floating out of the screens and into the air above you as the vibrations pulsed through your chair.

The band seemed fully aware of how lucky it was, and most of the audience seemed similarly cognizant. A relief, considering what some of them paid. There were far fewer cellphones in the air than one might expect based on the videos that emerged from U2’s Sphere run, and far less shouty chatter. Instead, a hushed awe often took hold of the crowd, and grew particularly acute during songs like “Divided Sky.” The emotional peak of the run came during the encore on night two, when Phish performed its ’90s power ballad “Wading in the Velvet Sea,” a song that famously brought McConnell to tears when he sang it during what was to be Phish’s final performance in 2004. Twenty years later, 40 years on from the band’s formation, the Sphere version was accompanied by images of Phish's members and their families, spanning the group's history, from when they were just kids goofing around in a band to their current incarnation as dads still goofing around in a band, while taking it very seriously at the same time.

Music, the most temporally bound art form, has a funny way of leapfrogging through time; a song can collapse the distance between otherwise disparate moments of our lives. Seeing the floating photos of these four friends laughing together across decades, still together after all these years, underscored how rare and precious this phenomenon is. Who among us gets to hang out and be creative with their best friends from childhood as part of their jobs? And how much longer can this go on before someone gets tangled in a guitar cord while jumping on a trampoline and fractures a hip? But the montage was also a reminder that in live music, spectacle (and even awe-inspiring scale) are a means to an end; whether inside the world’s largest manmade spherical object or in the back of a bar, the audience’s emotional reaction is what matters.

What’s thrilling about Sphere at this juncture is that as much as Phish achieved, the potential of the place has yet to be fully tapped. It will be exciting to see what a Taylor Swift, a Harry Styles, or a Beyoncé might do with all the state-of-the-art toys the venue has to offer. In a world of packaged, disposable content and mass experiences that leave little room for true surprise, there is a demonstrable thirst for unique experiences. It’s a market that Phish has tapped into and cultivated throughout its career, and if anything, Sphere simply gave the group a way to deliver its audience more of what they do so well.

Originally Appeared on GQ