Many of Our Favorite Nursery Rhymes Have a Sinister History

Understanding problematic conditioning, even when it is couched in nostalgia, is key to raising liberated children.

Adobe Stock/Kindred by Parents

Fact checked by Karen Cilli

As Black History Month approaches, it’s important to acknowledge some of the overlooked ways in which remnants of white supremacy still exist and filter into our lives. There’s no harm in being reflective and taking a hard look at our everyday routines and questioning deep-seated racism, even ones disguised as jovial jingles.

While many nursery rhymes from our childhood evoke warm feelings of nostalgia and fond familiarity, some of them have dark, sordid roots that give a very real insight into the level of racism that Black people faced for centuries.

Nursery rhymes can be dated back to the 18th century but their popularity really took off in the 19th century. According to a 2017 study, as well as supporting language and cognitive development, nursery rhymes are a useful tool for developing skills in communication. This includes communicating in socially and age-appropriate ways, understanding the symbolic use of language, storytelling, and gaining relevant knowledge about the world.

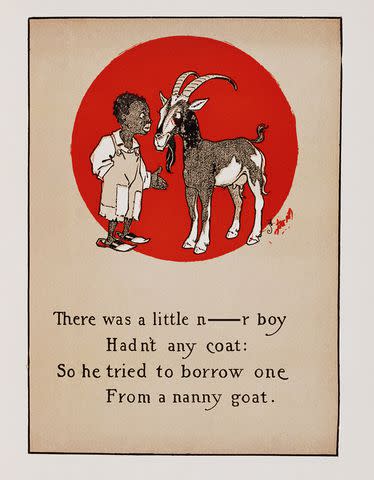

This connection between childhood development and nursery rhymes is what makes the nature of racism within some of them so insidious – children were being taught how to hate and how to engage with anti-Black rhetoric from a very early age. Hating Black people was woven into their education and their play.

Tiffany M. B. Anderson, assistant professor at Texas A&M, notes in her 2009 paper that white people “refused to compromise their ideology of the freed slaves’ inferiority.” She continues that the existence of these songs in children’s nursery rhyme books “represents the early racist indoctrination of children.”

Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

Let’s take a look at some of the lyrical atrocities to shed light on where humanity went wrong.

While you might be familiar with the watered-down version of "Eeny, meeny, miny, mo,” the real version packs a nasty punch:

"Eeny, meeny, miny, mo/Catch a n***er by the toe/If he hollers let him go/Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe.”

There were alternative endings such as “catch a negro by his toe, if he hollers, make him pay twenty dollars every day” and "every time the n***er hollers, make him pay you fifty dollars.” Each racist variety was connected to catching Black slaves as they tried to run away.

In his 1888 book The Counting-Out Rhymes of Children: A Study of Folk-Lore, Henry Carrington Bolton deep dives into popular "counting-out rhymes" sung by children at the time. He found several different versions of “Eeny, meeny, miny, mo” existed worldwide and a handful of them, largely around the USA, used the n-word followed by variations of “if he hollers/screams/squeals.”

The PC version of this rhyme is still popular today and is used by children worldwide to determine who is “it” in a game of tag.

Related: 8 Martin Luther King Jr. Quotes to Teach Our Children How Radical He Was

A more stomach-churning nursery rhyme is “Ten Little Monkeys,” and while it sounds perfectly acceptable, in its former racist glory the title and the words were a far cry from benign.

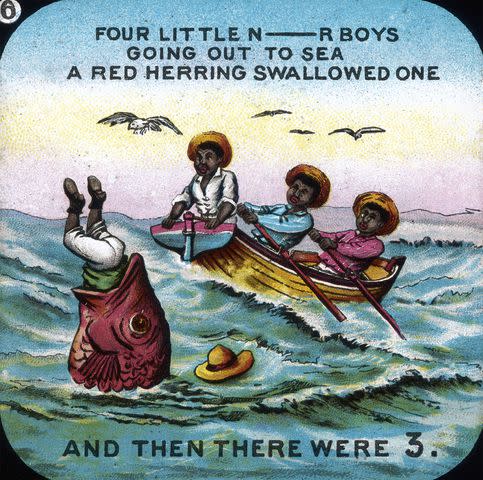

The original 1869 nursery rhyme was called “Ten Little N***ers” and it taught children to count backward by highlighting 10 different violently macabre ways for little Black boys to die. It was essentially a celebration of the demise of Black children, dressed as a sweet tune.

Some of the sinister lyrics included “ten little n***er boys went out to dine; one choked his little self, and then there were nine” and “seven little n***er boys chopping up sticks; one chopped himself in half, and then there were six.”

As highlighted by Anderson, “the white population who circulated the song intended to characterize the Black freedman as barbaric and ignorant, and the song also connected the white-constructed definition of ‘n***er’ to the Black man’s consciousness.”

“Ten Little N***ers” was so popular, it was heavily used in minstrel blackface shows and was even used by Agatha Christie in her 1939 novel of the same name, about ten killings on a remote island (eventually retitled “And Then There Were None”).

Another minstrel show hit was “N***er Love a Watermelon Ha! Ha! Ha!”, well-known now as the ice cream truck song or “Do Your Ears Hang Low?”. The original is debated to be “Old Zip Coon” which dates back to minstrel shows in 1834 but it was rewritten in 1916 as a folk song to further mock Black people, stereotyping them as dimwitted, clown-faced, watermelon-loving creatures. Regardless of the timeline of this song’s origin and history, it has always been firmly rooted in Black caricature and ridicule.

CORBIS Historical/Getty Images

The nursery rhymes mentioned (along with others such as Jimmy Crack Corn and Camptown Races) helped build a generation of non-compassionate, non-empathetic racists who, from childhood, took joy in the suffering of Black people. The fact that children well into the 1970s and 1980s were taught these offensive lyrics that advocated hate and normalized cruelty only further instilled racist ideologies that are now deeply ingrained in society and manifest as anti-Blackness.

Anderson describes this as “mental conditioning.” She goes on to write that these songs “taught white Americans how to view subjects that were previously objectified in the cloak of slavery and taught Blacks how to view themselves through the perspective of white Americans.”

The current dilemma is what happens when our Black children come back home from school and sing one of these nursery rhymes with origins of Black hatred. Should we move on and accept that changing the racist lyrics counts as effective action? Should we expect schools to do more to work towards eliminating these songs from our children’s formative years? Or do the child development values of learning these specific traditional nursery rhymes outweigh their historical context?

Though their words have been modified, the recognizable melodies of these nursery rhymes are still a scar to the Black community and a stark reminder of the trauma inflicted in the very recent past.

It should be acknowledged that these songs were not created for everyone to share and enjoy equally—they were created to ensure Black people were dehumanized, a laughingstock, and a source of white entertainment. If we are being fair and honest, they have no place among future generations but if they need to exist, they should do so only as a means of educating age-appropriate students on America’s racist roots.

For more Parents news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Parents.