The Journalist Who Brought Down Jeffrey Epstein Still Has Questions That Drive Her Crazy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

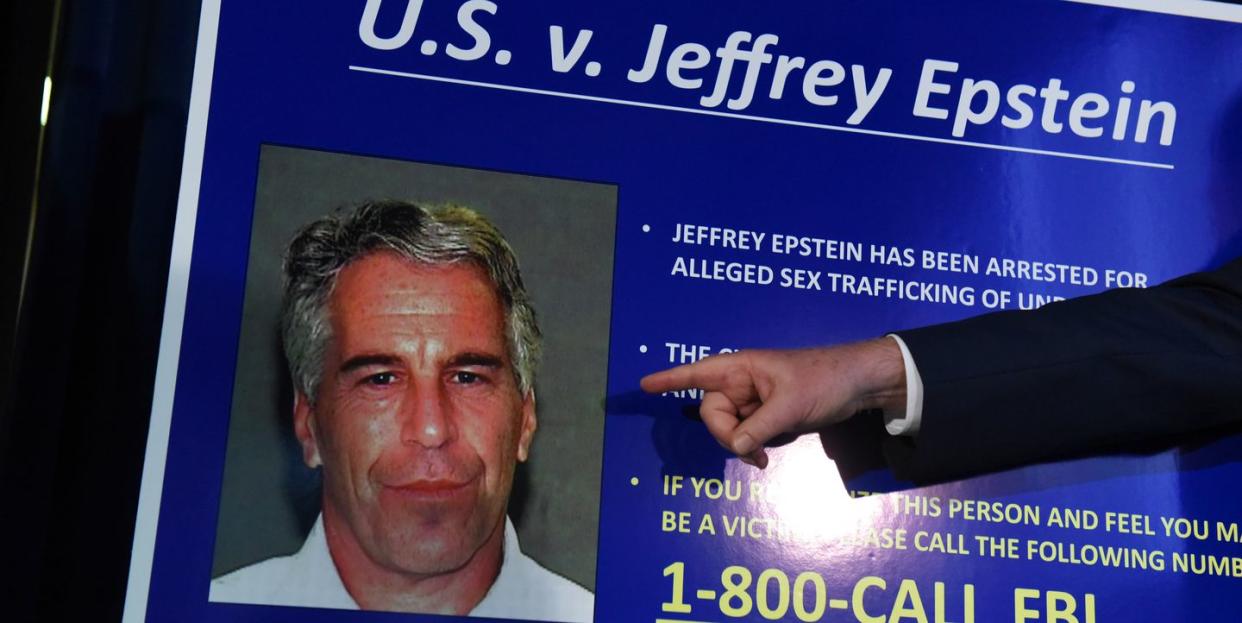

In 2018, Julie K. Brown wrote a trio of articles for the Miami Herald about a decade-old plea deal Jeffrey Epstein received on charges that he sexually assaulted numerous teenage girls. The case had already been covered extensively—including by the Herald—but Brown broke new ground by exposing how Epstein used his wealth and connections to sidestep meaningful punishment and by describing the devastating effects his crimes, and the failure of the criminal justice system to hold him to account, had on his victims.

The series set in motion a massive reexamination of the case. Other news organizations launched their own new investigations as did federal prosecutors. Epstein was soon arrested and the former prosecutor who okayed the lenient deal—Alexander Acosta—faced such intense criticism that he resigned from his position as President Trump’s Secretary of Labor.

The series won multiple awards and Brown and her colleague Emily Michot [a visual journalist at the Herald who photographed victims and filmed interviews for the digital version of the piece] continue to be lauded for their exceptional work.

In a new book out this week, Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story, Brown describes the months of reporting and legwork she and her colleagues put into those stories, and even though many of the facts of the case are now familiar, it's a harrowing and illuminating read. Ahead of its publication, the author spoke to T&C about the challenges of reporting the story and the questions that still driving her crazy.

People had been writing about Epstein for years when you started on your articles. What made you think there was something new?

Look, this story was a big open secret for a very, very long time. A lot of attempts were made to do it in a different way, but in most cases it just didn't resonate because, in my view, anyway, the focus wasn't on the right thing. Much of the emphasis in the past was on the celebrity aspect: you know, Bill Clinton, the “Lolita Express,” and the “Pedophile Island.” I just kept shaking my head thinking, none of this tells me how it happened.” Then I thought, what if I try to take this apart like a cold case detective and start from the beginning and look at every single thing again? Maybe, after all this time has gone by, somebody who has information might be more willing to reveal it than they had been before.

Was there a specific moment when you knew you were onto something?

It wasn't just one thing, like reading the court documents or interviewing the victims. A lot of aspects sort of crystallized at the same time. But I do think getting the lead detective and the police chief to cooperate with me was a huge part of the story. In my view it was almost as important as getting the victims to talk because the two of them had never given an on-the-record interview before. They had talked to a lot of journalists off the record. But as you know, it's much more powerful to get people to put their name to a story, and to say, here's what happened.

You spend a lot of time in the book describing things that almost derailed your investigation. Why was this important to include?

I don't think a lot of people understand the process—mostly because we as journalists don't talk about it. For example, I hit a lot of dead ends—so many dead ends—and there is still stuff I want to know. I also had a lot of help along the way and I wanted readers to see how that part works. For example, Monika Leal [the Herald's director of information services] tracked down crucial information about Epstein's past, his finances, and things like that. My editor, Casey Frank, was a big piece of it—we butted heads a lot but that was necessary and made for a better story. Emily Michot was often the voice of reason during the reporting. We have different personalities—it's good to have some say, “Maybe you should look at it from this point of view.” The list goes on.

What was the most frustrating dead end?

I think getting all the way to the part [in the investigation] where you know something happened at the very top and a decision was made to offer the plea deal [in 2008] but not really be able to reveal exactly who said, “We are not going to prosecute him.” We know that Acosta ultimately made that decision, but why? He had been fighting in Washington to have the power to prosecute Epstein. So it doesn’t make sense to me that he then decided not to.

And then there’s the fact that Acosta's emails from this time period disappeared. I mean, how does that happen? You know, there's no mention in the investigative report by the DOJ that they couldn't find anybody else's emails—just his. Why isn't some senator screaming, “Where are Acosta's emails?”

You focus a lot on how Epstein wielded money and political influence. Did any of it shock you?

I think the lawyer aspect of it. Why did the prosecutors work so closely with Jeffrey's defense lawyers? Even the civil lawyers did. It's a boys club in a lot of these wealthier communities where you have big-time lawyers and other people in power, like sheriffs and state attorneys, and they just pick up the phone and say to each other, “Hey, I want to meet with you.” If you have money or means, then all you have to do is hire one of them and they can just walk into the U.S. attorney's office or invite him or her for a cup of coffee.

You describe a rough patch in your own childhood. Did having had that experience help you understand the difficulties some of the girls Epstein victimized faced in their own lives?

I've done stories about vulnerable people throughout my career. I covered women in prison and crimes against young people. I guess I feel a kinship with people who struggle because I’ve struggled myself, and perhaps that helps me in my interviews with them. I remember talking to one [victim’s] mother, and she was describing how they never celebrated Christmas because she had to work that day. Instead, they’d picked another day that week to celebrate. Something clicked in my head—I hadn't thought about it in decades—I told her how my mother worked, too, and always waited until Christmas Eve to buy a tree and sometimes it was snowing and we’d almost not make it and it used to drive me crazy. It was a connection.

Did working on the book reveal anything new to you about the case?

One of the questions people sometimes ask me is, “Why do we need to care about this after all this time? Everybody knows about this story now.” But I don't think that we know everything about the story. Some of the victims continue to be angry because many of the enablers and other people who participated in this have not been held accountable. And I think it's important for investigators and the FBI and Justice Department to continue to probe exactly how this happened and why and then make improvements to the system so that it doesn't happen again.

You Might Also Like