John Fogerty Remembers Duane Eddy: ‘Unlike Any Guitar I’d Ever Heard’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

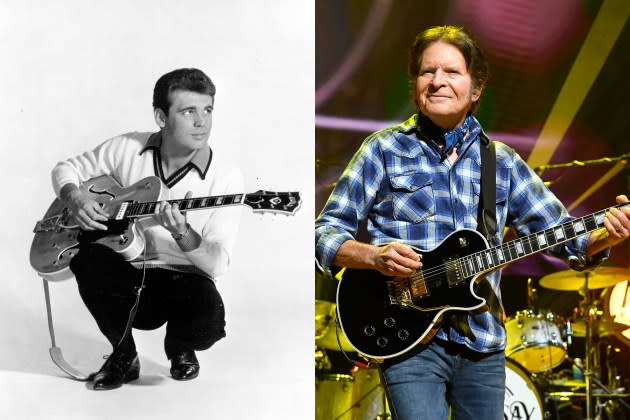

Starting with “Rebel-‘Rouser” in 1958, Duane Eddy’s instrumental hits from the early rock & roll era made the guitar the star of the show. On that song and those to follow, like “Peter Gunn,” “Cannonball,” and “Forty Miles of Bad Road,” Eddy used vibrato and lent his guitar a deep sound by emphasizing bass strings. In doing so, he influenced an entire incoming generation of guitar players — including Bruce Springsteen, George Harrison, Jimi Hendrix, and John Fogerty. After the news of Eddy’s death was announced on Wednesday — he died April 30 at 86 of complications from cancer — Fogerty spoke with Rolling Stone about the impact Eddy had on Fogerty’s music and his contribution to Eddy’s 1987 comeback album.

When I was 12 or 13, I remember hearing “Moovin’ ‘N Groovin’.” It was unlike any other guitar I’d ever heard. It had this wonderful, huge, big sound, and then he started twanging the strings. The sound was massive and the guitar tone was perfect; where he placed the notes made so much sense. Here was this guy not singing but just playing the guitar. I wasn’t singing yet, but he was exactly what I wanted to do. I was a fan of other singers, like Elvis, but Duane showed up just being the leader of the band. I thought he was the king right away. It was such an inspiration for me. You looked at his pictures and he was really good-looking and cool in a Fifties style, very much like an Elvis or a James Dean. There was some sense of defiance.

More from Rolling Stone

Billy Joel Is Ending One of the Longest Droughts in Music. Who's Next?

Five Decades Later, John Fogerty Finally Gains Ownership of CCR Catalog

Then I heard “Rebel-‘Rouser.” There was rock & roll and then, suddenly, “Rebel-‘Rouser” seemed to transcend everything. It was like, “Wow, he dares to do that?” “Moovin’ ‘N Groovin’” and “Ramrod” were great, but “Rebel-‘Rouser” had an actual melody, like a song, which was just so unusual. I started buying his records. The whole first album, Have ‘Twangy’ Guitar Will Travel, was just a masterpiece. I still think it’s one of the greatest albums ever made: the music just flowed, and all the songs are wonderfully recorded and wonderfully played. Also, on that first album, you saw that he had a “recording band” and a “traveling band.” Not that that I took that [phrase, for the Creedence Clearwater Revival song] or maybe I did; it’s hard to say. But I got the idea that recording involved more and more people and the traveling band was pared down for the rigors of the road.

Another thing that was very inspirational to me was the fact that Duane was playing instrumentals with no lyrics, but the titles of his songs were very imaginative. “Cannonball.” “The Lonely One.” “Forty Miles of Bad Road.” All those titles evoked an image in your mind about the music as you listened to it. He could have had a track and called it “XYZ Blues” — it wouldn’t have mattered, because there were no lyrics. But he used a lot of imagination to give you a greater sense of the song. He was expanding the persona of his song and his records.

The first time I saw Duane, I went to an Oakland Auditorium extravaganza show with many acts on it, probably around 1958 or 1959. There were three yet to be members of Creedence Clearwater sitting in the front row, watching Duane at that show.

There was an underlying country element in his music on a song like “Detour” on his first album. And that showed up for me when I did something like my song “Big Train (from Memphis)” or “Cross-Tie Walker” on the Green River album, where Duane’s influence was specifically stylistically hitting me.

In 1987, I moved down to Los Angeles and was staying at Howard Johnson’s in the San Fernando Valley for a week or so. One day I went down to the club or bar in the hotel; in those days, I would stay too long in that place, put it that way. And there was Duane sitting in the club and we struck up a conversation. He was very nice, very friendly. It turned out he was working on an album, and I heard his room number and realized I was in the floor right above him. I couldn’t believe it! I was mystified in a way that a little boy is meeting his idol.

Then he said, “Why don’t you come over to studio? I’d like you to be on the record.” Oh, man. Wow. I was taken aback. I went to the studio and there were James Burton and Steve Cropper. Duane was working with some pretty heavy-hitters there, but we were all very deferential to him. He was a guitar god to us, the inventor of this wonderful thing. He was very warm and gracious and had this effortless way of getting that to happen in the studio. He had what some people would call a dry sense of humor. He would say something but not bust himself up. He just said it. And then you busted up.

When I was about 14 and Duane was the king of the guitar on the radio, I said to myself, “You know, someday there’s going be a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and Duane Eddy is going to be in it.” Of course, none of those things existed when I was saying this around 1960. Lo and behold, Duane got inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame [in January 1994], and they called me up and said, “John, we’d like you to be the one that inducts Duane.” I said, “Fantastic.” I’m all ready to fly to New York, probably two days before the ceremony. Then I get awakened in Southern California at 4:31 in the morning by a giant earthquake. Our house was about 40 percent destroyed. That changed our plans immediately. I realized we’re not going to the airport this morning and leaving our young children behind, so I had to call up the folks at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

A couple of days later, I woke up that morning in California and said, “Well, today’s the day they’re going to have the ceremony and they’re doing it at the Waldorf Astoria,” and I thought, “Duane’s probably staying there.” So about seven o’clock his time, I called up the hotel and asked for the room of Duane Eddy. And they put me through! I said, “Hi, Duane, this is John Fogerty.” He says, “Hi John,” in that low voice, and I said, “Congratulations to you. I know you’re about to go downstairs to the ceremony and I’m really disappointed that I won’t be able to induct you, so I want to read my speech to you in case you know, the other guy doesn’t do it.”

Then I read Duane my speech over the phone. It was just a really wonderful moment for me. He was probably a little embarrassed, since I’m sure I was pretty flowery about it all. But he was the face of guitar for quite a while in rock & roll.

Best of Rolling Stone