Jerry Seinfeld Says Movies Are Over. Here’s Why He Made One Anyway

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

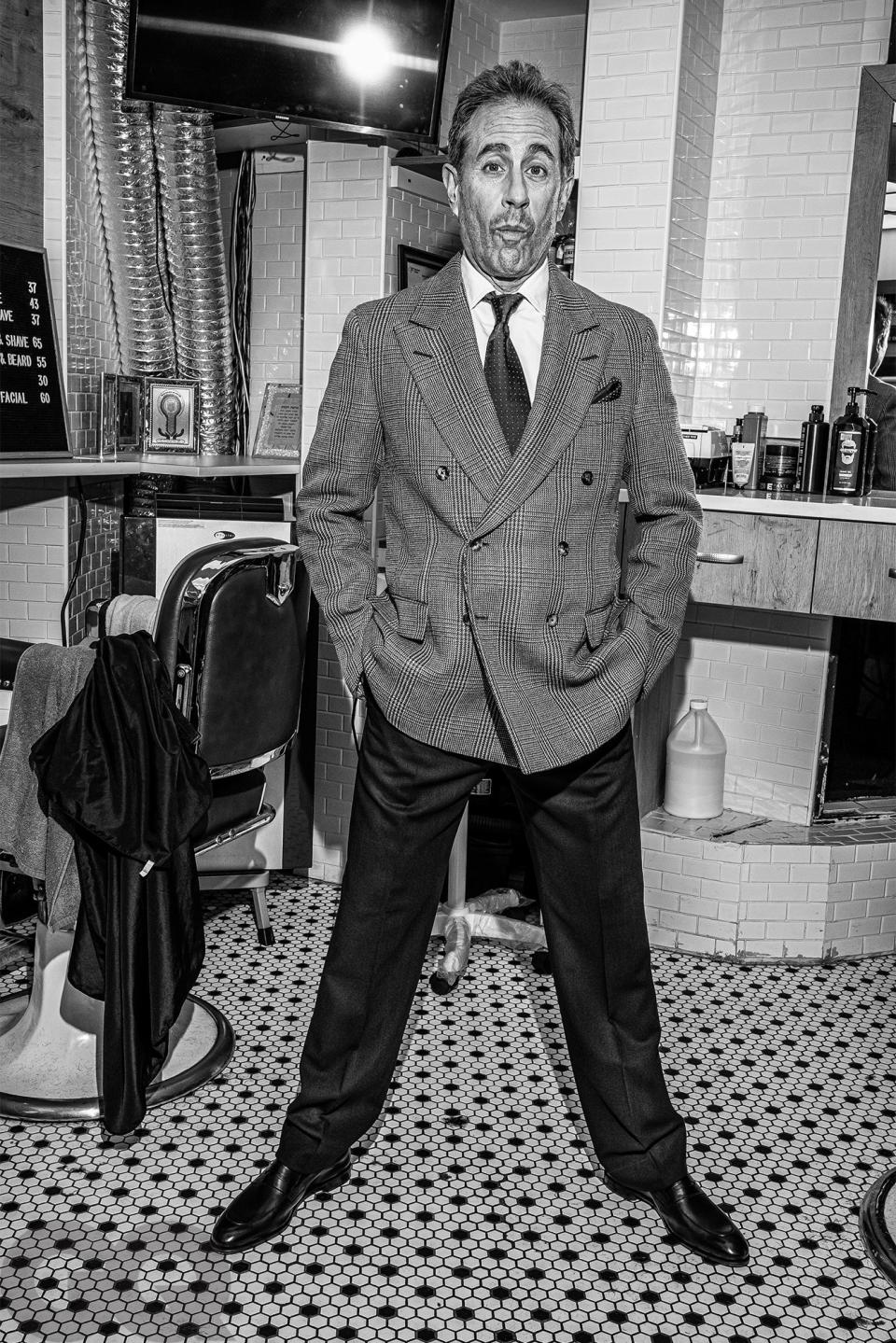

Vest and tie by Drake's. Shirt and pants by Isaia.

Of all the things one might associate with Jerry Seinfeld, excited sentimentality might be the last. But remembering the day he shot the recent finale of Curb Your Enthusiasm, his voice approaches something dangerously close to swelling. “As I drove home that night, my scalp was just tingling. I thought what we had done was just the coolest, wildest, most remarkable thing,” he says of his surprise (though much guessed at) appearance. It was, he says, the callback to end all callbacks, a comedian’s dream. “What you have there is a joke that was set up 25 years ago and then paid off 25 years later! How do you even describe something like that?”

“It was so much fun,” says Larry David, who admits that he once swore to GQ that he would never, ever attempt something like the original Seinfeld finale. “What changed is that we started with this premise of Larry getting arrested for giving water to somebody on line to vote and it was like, ‘Where are we taking this thing?’ That’s when [executive producer and director] Jeff Schaffer had the idea. I said, ‘Okay, sure, let’s do the same terrible thing again.’ People hate it! Jerry loved the idea. He was game immediately.”

“We all got very excited: ‘Let’s talk about the finale in the finale!’” Seinfeld says of the scene’s final line. “It was absolutely one of the highlights of my professional life.” After a small bit of prodding, David also admits to feeling a small bit of closure and peace.

On this bright day, Seinfeld is sitting in a conference room high above Manhattan, the view stretching out toward the Upper West Side, a domain over which Seinfeld remains the undisputed master, if you will. Curb’s callback only put a finer point on how firmly entrenched in the culture Seinfeld, the show, still is—a guest that checked out a quarter century ago, but never really left the premises. Of course, the version of New York he made famous is long gone, as lost a world as the 1960s in which his new movie, Unfrosted, is set. Seinfeld is philosophical about it. “Every world is lost. It’s all lost,” he says. “Whatever you remember, it’s gone. Forget it. One of people’s great foolishnesses is thinking, This is the way it is.”

Some things do stay the same, however. For instance, breakfast.

One of the earliest bits that Seinfeld performed in a stand-up career now entering its sixth decade was about cereal—“Where in the world do you get your balls to call a breakfast cereal LIFE?”—and his attention has never waned. According to David, the legendary moment in which he and Seinfeld met in the aisle of a New York supermarket and conceived of a show about nothing, the two were talking about…you guessed it. “That’s what we were discussing in that grocery store, when I said, ‘This is the show.’”

Seinfeld has never made a mystery of what interests him and what doesn’t. The one regular gig he’s had since Seinfeld laid it out plainly: Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee is as concise a portfolio as you’re likely to get—even in the correct order. There is no shortage of comedians ready and willing to heroicize stand-up, but nobody has been more insistently single-minded in their devotion to the art, craft, and performance of that medium than Seinfeld. Even during the run of Seinfeld, you got the feeling he viewed the show as an unfortunate diversion from his real work. Since the show ended, he has barely done any other kind of work. Watching him onstage, you notice that his elbow falls naturally into the precise bend for holding a microphone up to one's mouth, as though he evolved for this and only this: Homo comedius.

It’s surprising then that, on the verge of 70, he is trying something completely new: making his directorial debut with Unfrosted, which is both a story of the creation of the Pop-Tart, and a kind of lunatic apotheosis of Seinfeld’s breakfast obsession. The film is set in cereal Valhalla, Battle Creek, Michigan, in the early 1960s, an era that has long fascinated Seinfeld and from which, it sometimes seems, he leapt directly into the 1980s. The story, the brainchild of Seinfeld writer Spike Feresten, centers on the warring cereal giants Kellogg’s and Post, and the race between their two heads (played by Jim Gaffigan and Amy Schumer) to invent a new breakfast category. It is the movie equivalent of the Seinfeldian stand-up method of working a concept from every possible angle, milking every possible joke about the most important meal of the day until there isn’t a drop left in the bowl. (For all that, it’s only moderately more batshit than the real history of Battle Creek, which is its own rabbit hole, if you have an hour or 10.)

The past year has also brought more unfamiliar territory. Seinfeld traveled to Israel immediately after the October 7 attacks by Hamas and posted several social media posts generally supporting Israel. This has brought an unaccustomed level of attention and vocal protest to somebody who has generally been resolutely apolitical.

But for now, it’s morning, so we begin…where else?

What is so funny about breakfast?

Everything! I love the great dumbness of life.

There’s dumbness everywhere. Why do you keep returning to this corner of it?

There’s dumbness everywhere. But I really do love cereal. I love the wetness and the crunchiness. I love spoons. I love bowls. When I was single, in my kitchen, I would keep a bowl with the spoon in it and my friends would laugh. Why take it out of the bowl? That’s where it’s going!

Larry David told me that it was because there’s a k in breakfast. He says that everybody knows k is the funniest letter.

Oh, yes. Everybody knows. K or c. It’s the sound. When you’re trying to get people’s attention in a crowded nightclub, they can hear k.

You’ve made the point that we all know you could be doing anything you want. So why this movie?

Because they wouldn’t put me in Mad Men. I love that kind of comedy. I love office comedies. I love stupid people in suits. And it was Covid. I had nothing to do. So I got talked into it. It wasn’t my idea. Seinfeld wasn’t my idea either. I keep getting dragged into things and surrounded by the most amazing people. These movie people are unbelievable. They’re insane. Like we had a prop master, Trish Gallaher Glenn. She had a room and it was floor-to-ceiling toys and bikes and clothes, everything from that era. Everybody does their job 150%. It is weird.

It’s sort of amazing that this was new to you, this late in your career.

It was totally new to me. I thought I had done some cool stuff, but it was nothing like the way these people work. They’re so dead serious! They don’t have any idea that the movie business is over. They have no idea.

Did you tell them?

I did not tell them that. But film doesn’t occupy the pinnacle in the social, cultural hierarchy that it did for most of our lives. When a movie came out, if it was good, we all went to see it. We all discussed it. We quoted lines and scenes we liked. Now we’re walking through a fire hose of water, just trying to see.

What do you think has replaced film?

Depression? Malaise? I would say confusion. Disorientation replaced the movie business. Everyone I know in show business, every day, is going, What’s going on? How do you do this? What are we supposed to do now?

Do you feel the same way, or are you grandfathered in?

I’ve done enough stuff that I have my own thing, which is more valuable than it’s ever been. Stand-up is like you’re a cabinetmaker, and everybody needs a guy who’s good with wood.

Break down that metaphor for me.

There’s trees everywhere, but to make a nice table, it’s not so easy. So, the metaphor is that if you have good craft and craftsmanship, you’re kind of impervious to the whims of the industry. Audiences are now flocking to stand-up because it’s something you can’t fake. It’s like platform diving. You could say you’re a platform diver, but in two seconds we can see if you are or you aren’t. That’s what people like about stand-up. They can trust it. Everything else is fake.

You’ve talked about how stand-up is about power: standing onstage, alone, demanding that people listen and have a physical reaction. How did the power of being a director compare?

Being a director feels like running a ranch in the West. It’s kind of a mess. You’ve got horses and cattle and chickens and broken fences and filth. You’ve got a lot of people and a lot of physical things. Stand-up is this very pure experience. This is why I’m so addicted to it. The only other thing in life that I truly idolize is surfing. I watch a lot of Instagram surfing videos, and when somebody catches a great wave and they’re just sliding down it, it just hypnotizes me. That’s how it feels when you’re having a good set—like you’ve caught this gigantic energy and are just sliding down it. There’s nothing pure in making a movie. There’s no flow. It’s highly complex and messy.

Do you surf yourself?

No, I tried. I did it for about a week, 20 years ago. You have to dedicate yourself to these great things. And I don’t believe in being good at a lot of things—or even more than one. But I love to watch it. I think if I get a chance to be human again, I would do just that. You wake up in the morning and you paddle out. You make whatever little money you need to survive. That seems like the greatest life to me.

Or you could become very wealthy in early middle-age, stop doing the hard stuff, and go off and become a surfer.

No, no. You want to be broke. You want it to be all you’ve got. That’s when life is great. People are always trying to add more stuff to life. Reduce it to simpler, pure moments. That’s the golden way of living, I think.

The other thing about this movie is how Midwestern it is. When you started going out on the road, after being raised on Long Island and living in New York, places like Battle Creek must have seemed like Mars. What was the Midwest like to you?

Hilarious. John Updike had the greatest line: “New Yorkers think anyone who doesn’t live in New York is in some sense kidding.” That was me. I felt like, Let me go to this place and show them what we are like, and they will pay to see that. I still feel like that’s what I do: Let me show you what a New Yorker is like. I think you’ll find it interesting.

This is what I think of as the Seinfeld paradox: It’s so specifically New York and so specifically Jewish, and yet there’s a station where I live, in New Orleans, that as far as I can tell plays only Seinfeld 24/7. I’m sure there’s also one in Omaha and Louisville and everywhere else. This has always seemed mysterious.

Well, let me solve the mystery for you. It is Jason Alexander, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and Michael Richards. Those three people transformed this very small, idiosyncratic thing, which should have always been small and niche. They made this unrelatable material accessible. There’s no other way it would have happened.

You don’t feel like you were a part of it?

I was part of it. But I wasn’t on their level. I did what I could to help.

Had the Seinfeld finale bothered you all these years?

A little bit, yeah. I don’t believe in regret. I think it’s arrogant to think you could have done something different. You couldn’t. That’s why you did what you did. But me and Jeff Schaffer and Larry were standing around, talking about TV finales and which we thought were great. I feel Mad Men was the greatest. A lot of people like the Bob Newhart one. Mary Tyler Moore was okay. I think Mad Men was the greatest final moment of a series I’ve ever seen. So satisfying. So funny. And they said that they had sat and watched the Seinfeld finale, trying to figure out what went wrong. And it was obviously about the final scene, leaving them in the jail cell…

I think it’s the opposite! I think that, just like Mad Men, in fact, the bulk of that final episode is forgettable—because it was a clip show—but the last moment is perfect.

Why?

Because it was this aha moment about what those characters really were and where they belonged. I assumed that it wasn’t really prison, it was hell.

See, I don’t agree with any of that. I think we were affected by some things that people had said, that they were selfish or whatever. And looking back on it, I think they were great! I love them. First of all, you’re not doing comedy without self-directed individuals. That’s an essential element of comedy, since Shakespeare and forever. You can’t do comedy without selfish people. That’s what people relate to.

This is all before the era of TV antiheroes. Do you think that people’s perception of them has changed in retrospect?

They think they’re funny. Nothing else matters.

A long time ago, I interviewed Alan King and he told me a story about when he knew everything about comedy had changed. He was doing a show uptown and afterwards he and Fat Jack E. Leonard went downtown to this club to see this guy work. “He started talking about himself. Instead of, ‘This guy goes to a doctor,’ it was suddenly, ‘I went to the doctor.’ Instead of ‘A man says to his wife,’ it was ‘I said to my wife.’” And then King said, “The name of that comedian was…”

And you thought he was going to say Woody or Lenny or somebody like that.

Yes, exactly. Instead, he said, “The name of that comic was…Danny Thomas!” Who, to me, was as old-fashioned as could possibly be. My point is that the question of how personal a comedian should be, and how much of his or herself they should reveal, has been around for a long time. And you’ve always put yourself squarely on the more old-fashioned side of revealing very little about yourself.

I do this one bit about “I don’t have arguments with my wife. I don’t think things that are in conflict with my wife.” Now when I say those things, the audience knows that they can’t be true. But they don’t care. They don’t care, because they want to hear the joke. The great joy to me is: I’m making this up, but let me see if I can make it sound like it makes sense to me. That’s what comedy is to me. They know I’m lying from the first line, and they don’t care. I always say, I don’t want to hear amusing anecdotes from your journal. Tell me about something that couldn’t possibly have happened. That’s what I want to hear.

Does it make you feel out of step?

I just think if you are a comedian and you want to survive, your only flotation device in the oceanic waters of show business is real laughs. When you’re young and cute and interesting and 23, or 33, a lot of things work. When you’re 53, if you want people to get in their car, and pay cash, and schlep into those seats…it’s harder. I would just caution the next generation, if you want to do this your whole life, which every comedian does, make sure you’re getting real laughs.

Are you saying the more confessional style of comedy is anti-laugh?

No, no, no. I’m saying I know a million comedians whose work dried up at 53. You’ve got to be ready for that. Make sure you’re working to be ready for that.

You talk about the life-or-death stakes of getting laughs in your preface to Michael Richards’s new memoir, and the Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee episode with him is very moving. Would you like to see him performing again?

If he wants to. I think he’s one of the most talented performers I’ve ever seen in history. I actually had a great thing for him in the movie. He was going to play my father. We wanted to come up with a tragic childhood story that made me want to invent the Pop-Tart, and it was going to be the death of my father trying to make bacon and eggs. But it didn’t survive.

The movie has a very funny January 6 parody in it, which was a little surprising, given how apolitical you’ve been. And then there’s been the response to your trip to visit Israel a few weeks after October 7. Tell me about the decision to do that.

Well, I’m Jewish. And you grow up learning about antisemitism, but it’s kind of in a book. It never crossed my mind that people would look at me as anything other than, “I like this comedian. I don’t like this comedian.” I think most Jews of my generation never thought about antisemitism. It was from history books. And then it was something different. It was something different.

Were you surprised by the reaction?

Every Jewish person I know was surprised by how hostile the reaction was.

Do you regret it?

No, not at all. I don’t preach about it. I have my personal feelings about it that I discuss privately. It’s not part of what I can do comedically, but my feelings are very strong.

How are you feeling about turning 70?

I don’t care. Zero. I used to talk about my age in my act when I was in my mid-60s, but 70, I haven’t found what’s funny about it. I don’t think audiences would find it funny. I think it would upset them. It doesn’t upset me. I think it’s funny and meaningless. But I think they come out and they feel in their minds like it’s a couple of years after the show ended. I don’t want to upset them. I’m there to make them happy.

Here we are in baseball season. My question for you, as a fellow Mets fan, is how do fans of other teams live with announcing teams so inferior to Gary Cohen, Ron Darling, and Keith Hernandez?

I have no idea. I couldn’t watch it. They spoil you for everybody else. There are some others that I like, but nothing beats Gary, Keith, and Ron. And it really is Gary. He brings it on another level.

Here’s a thought experiment: What if you had to choose between winning the World Series but losing Gary, Keith, and Ron? I’m glad that nobody has given me that power to decide. Because I’m with them 130 nights a year; it would be only one night that we won the Series.

That is fantastic. But what you forget is how every other day you’re not going to feel good, depending on whether they won or lost the night before. Somebody asked me the other night: Would I trade my comedy career for playing 10 years on the Mets and we win the World Series and I go to the Hall of Fame. And I said no, because 10 years is still too short. The thing about Gary, Keith, and Ron is, there are few people in life that seem happy doing what they’re doing. These guys go to the park every day and they’re happy to be there. And I think that adds an undercurrent of relief. It’s a relief to be around people who are happy doing what they’re doing. Maybe that’s another reason people go to see comedians. I’m not trying to be anything else. When I walked into a comedy club the very first time, I was probably 18, that was the first time as a human on earth that I felt like, Oh, I’m home.

I’ve been thinking about that time frame. We’re talking about the early 1970s. You’re feeling stifled in the conformist Long Island suburbs. You’re right on time to grow your hair long, take acid, and join the counterculture. Were you even tempted by that path?

I was. But stand-up comedy is growing your hair long and taking acid. Just verbally. That’s what it is. And I mean, I was skydiving. Riding my motorcycle very riskily. Pot smoking. All of it. As soon as I got into stand-up, I was like, I don’t need any of that crap. I’m done with all of it.

Does anybody, say your wife, ask when you’re going to stop?

People who know me know that every other part of my life is a tremendous effort, and difficult to enjoy. I have a wonderful family. I have good friends. I’m just sick of the chicken. I don’t want to go out and have chicken anymore. It’s the same goddamned thing over and over. It’s just chicken. But stand-up—and I really have to apologize for belaboring the surfing analogy—it’s always the ocean, but every wave is different.

I’m actually glad you brought it back up, because I can’t stop thinking about how you watch it and love it but aren’t interested in actually doing it.

There’s nothing I revile quite as much as a dilettante. I don’t like doing something to a mediocre level. It’s great to be 70, because you really get to preach with some authority: Get good at something. That’s it. Everything else is bullshit.

Brett Martin is a GQ correspondent.

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Bruce Gilden at Magnum Photos

Styled by Brandon Tan

Tailoring by Ksenia Golub

Grooming by Rebecca Restrepo at Walter Schupfer Management

Special Thanks to Barber Shop NYC

Originally Appeared on GQ