Growing Up Rich and Utterly Wild in 1980s New York City

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

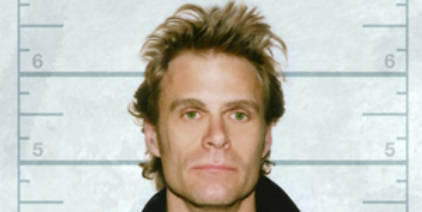

Rob Sedgwick, whose younger sister is the actor Kyra Sedgwick, grew up in a prominent New York City family in the 1970s and '80s. He bounced around private schools in his teens and found some success as an actor in his early twenties. But then one day police raided his Upper West Side home (his grandparents’ 12-room apartment; they were in the West Indies) and discovered 250 pounds of marijuana.

The bust is the backdrop for Sedgwick’s Bob Goes to Jail, published this week by Rare Bird Books, which describes the circumstances that lead him to suggest to a drug-dealer acquaintance that his grandparent’s doorman building would be a perfect place to base operations. The book offers vignettes from his childhood and describes his drinking and drug use, but Sedgwick cautioned in a recent phone conversation that readers should not expect a typical memoir. “There is no redemption narrative here,” he said.

“I wanted to describe things I experienced because I think they are interesting and hopefully shed light on a time and place that doesn’t exist anymore.”

Sedgwick was raised during a pre-helicopter moment in parenting that turned many Manhattan kids (including rich ones like him) loose on a still ungentrified city. He sailed from Upper East Side living rooms to downtown mobster hangouts to strip clubs (where his girlfriend moonlighted) to TV and film studios with unadulterated glee. Along the way, he meets a cast of fascinating characters.

Sedgwick, who has been sober for 25 years and now teaches acting, started out writing his story as a script for a one-man show, but then a friend read it and suggested it would work better as a book. He took the advice, arranging the narrative into scene-like chapters. Many are deceptively benign—he and his siblings move into an opulent new home after his mother remarries. Others are exuberant—he rolls around on his bed covered in thousands of dollars after the first big deal. Some are enraging—a young Rob realizes at the moment of his arrest that he’ll get off easy because of the color of his skin.

“I know parts of it are not pretty. I was a schmuck who made every bad decision possible. But I wanted to render this person—myself at that moment—and the other people around me accurately. It was a crazy time and you have to look at it head on. Otherwise, why bother?”

Chapter One of Rob Sedgwick's Bob Goes to Jail is excerpted below with the permission of Rare Bird Books.

So I had the load in front and Jordan had the load in back, and Jordan was saying:

“Cash, cash, cash!”

I looked up, and there were eight to 10 guys streaming into the lobby with more artillery than you’ve ever seen, and it just looked too real. I figured they had to be water pistols because they looked too detailed, too significant, too vivid to be really real. My mind slowed everything down like Joe Montana, like Larry Bird. At first I thought: This is Jordan’s birthday. These are friends of Jordan’s that I don’t know.

And then I thought: No. This is a joke. This is a joke, and these are friends of Jordan’s that I don’t know, even though I know all of Jordan’s friends.

And then I was spun around, and I saw myself in the lobby mirror with one of those cylinder machine guns at the base of my brain and another gun at my side and one to the middle of my back. They swung me back around. One guy was pistol-whipping Jordan on the ground as they dragged me to the elevator.

At the elevator was a prominent sign that read: “No more than five people on the elevator at one time.” All eight of us got on. It stalled.

One of the guys brought out one of those huge hammer jobs that belonged on an anvil and started hammering the side of the elevator. “I can get the car moving again,” and they responded, “You better not do anything stupid.”

I had three guns on me, and I was cuffed. Who am I, Bruce Lee?

I placed my foot on the sliding door of the elevator and pushed it open, and that reactivated whatever ancient mechanism was on the fritz. We were on our way up. I told the guys about Tybalt, my dog—the love of my life, the reason I dragged my ass out of bed in the morning, usually clobbered with a hangover mean enough to paralyze a small county.

They said that if he did anything they would have to shoot him.

Then one of the guys—Andy, I would find out later—said overlapping, “Look, I got dogs, I know how you feel. I’ll let you in the apartment first. If you can settle him down and if he seems okay, we won’t shoot him.”

I didn’t give a shit about myself at that moment. If they shot my dog, I’d be next.

I opened the door and spoke to Tybalt. He understood immediately that I was in deep shit and that this was no time for monkey business. He backed up slowly, carefully, no fast moves, giving the semi-frenzied men a wide berth so they knew this was their ball game, that everyone else’s rules were out the window. His paws were practically up. Then he sat solemn and calm to cool everyone off. It worked. The pack of humans took a collective breath, and in a couple of brief but precious seconds everything went from scary to just really bad and everyone’s trigger fingers seemed to relax.

I knew these guys were some kind of cowboy superhero cops; as we entered the apartment, the first words out of anybody’s mouth were not Miranda but “Where’s the cash? Where’s the cash?” There was no Miranda warning until we were well into the apartment. There was our first load: a refrigerator box filled with 250 pounds of dope, standing sentinel in the dining room like an upright coffin. And there were all the other accoutrements: Hefty trash bags to be filled; Bounce to offset the scent; duffel bags from the now sadly defunct Morris Brothers (a neighborhood store across the street that had been around since before NBC had a color peacock), which would later be filled with pot to sell to other drug dealers; and a scale.

We were caught on the shitter in the midst of shitting.

The TV was on in the living room, the Knicks playing the Larry Bird Celtics, and one of the guys started doing dips on an exercise bar I’d set up near the TV to work on my lower pecs and triceps when there was a game on. He could barely hoist himself up once, but there was something in his bumbling effort that made him seem almost sweet.

Ralph Scott, soon to be revealed as the bad cop, asked me again where the cash was.

I said I didn’t know.

He indicated the refrigerator box filled with 250 pounds of pot and asked me if that was for personal use.

I told him no.

He asked what the Bounce was for. And I told him.

He asked me what the trash bags were for. And I told him.

He asked me who Jordan was. I told him Jordan was in charge.

He nodded at the jar of Vaseline on the table in front of me (which I kept handy to smear on my winter-chapped lips) and suggested that I would need that in prison.

He wasn’t very nice, and it dawned on me that maybe I should stop answering Ralph’s questions and talk to a lawyer.

This time we left the apartment in two shifts so we wouldn’t stall the elevator. Amazingly, we didn’t run into any other tenants while leaving the building. I gave the narcy doorman a look because he always stared at me like I was up to something and I was sure he was the one who tipped off the Drug Enforcement Agency. On the way out, I twisted my body Houdini-style so my fingertips could sneak out the apartment keys to give the doorman so someone could take care of Tybalt.

Jordan had disappeared.

They shoved me into the cruiser. I looked out the windows at the Town Shop for Brassieres, Shakespeare & Co., Zabar’s, people freely walking up and down the wide boulevards of Broadway, doing stuff. My inalienable right to wander around footloose and fancy-free just got snuffed. I was in the back of a cop car with my hands cuffed behind me, headed downtown.

The agent driving me was the same one who couldn’t do dips.

The car was hermetically sealed, quiet. Almost serene. “What’s that exercise called?” he asked.

“Dips,” I said.

“Oh. And they’re for your…”

“Lower pecs and triceps mainly.”

“Christ, what a fat fuck. And to think I used to swim in high school, not drown, and actually beat people.” Then he said, as he casually turned down Twelfth Avenue, “I have a feeling things are going to turn out okay for you. I know they seem bad now, but I think you’re going to be all right.” Looking in the rearview mirror to catch his expression, I caught a glimpse of my own whiteness and figured it would give me a fairer shake.

We arrived at Fifty-Seventh and Twelfth, home of car dealerships and DEA headquarters. A shitty, almost deliberately depressing area of town. Jordan was already there. We were usually pickle silly with each other, but now there was no silly, only a peculiar amount of mouth tension. We looked at each other as if this were the betrayal-discovery-we’re fucked scene in a movie.

We were processed, fingerprinted, photographed, and put in a cell together, both of us very weirded out.

Jordan asked me what I told them and I said not much: just that the boxes were to be distributed, the Bounce was there to cover the odor, the bags were to divvy the stuff up, that we used the scale to weigh stuff, and that he—Jordan—was in charge.

Jordan said those were probably not good things to say.

Reprinted with the permission of Rare Bird Books.

You Might Also Like