What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in Mary and George

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Mary and George—a dramatization of the stratospheric rise of the Villiers family to power and influence during the reign of Elizabeth I’s successor James I—is one of the new breed of period dramas like The Great or The Favourite, where, apparently unconstrained by the rigid social mores, constricting formality of dress, or religious edicts of their time, characters behave like contemporary privileged libertines, indulging in ripe swearing and over-the-top sexual activities. At least in this case, the show’s creators can legitimately argue that the series’ baroque sex and graphic violence is in keeping with what Jacobean dramatists like John Webster put on the stage.

The ambition, superb strategic thinking, and ruthlessness demonstrated by the central figure, Mary Villiers (Julianne Moore at her most chilly), might seem anachronistic, but she really was that much of a girlboss, climbing from relative obscurity via advantageous marriages (the usual and indeed only way for a woman to better her social position in 17th-century England) to become a countess and one of the most powerful women in the country. So along the way, her rise might have included pimping out her son to the king, kidnapping her future daughter-in-law to force her into an unwanted marriage, and committing another son to an asylum, but hey—the path to power is never easy. Mary did in fact do all these things, as shown in the series, but there is scant evidence for the murders the show also attributes to her.

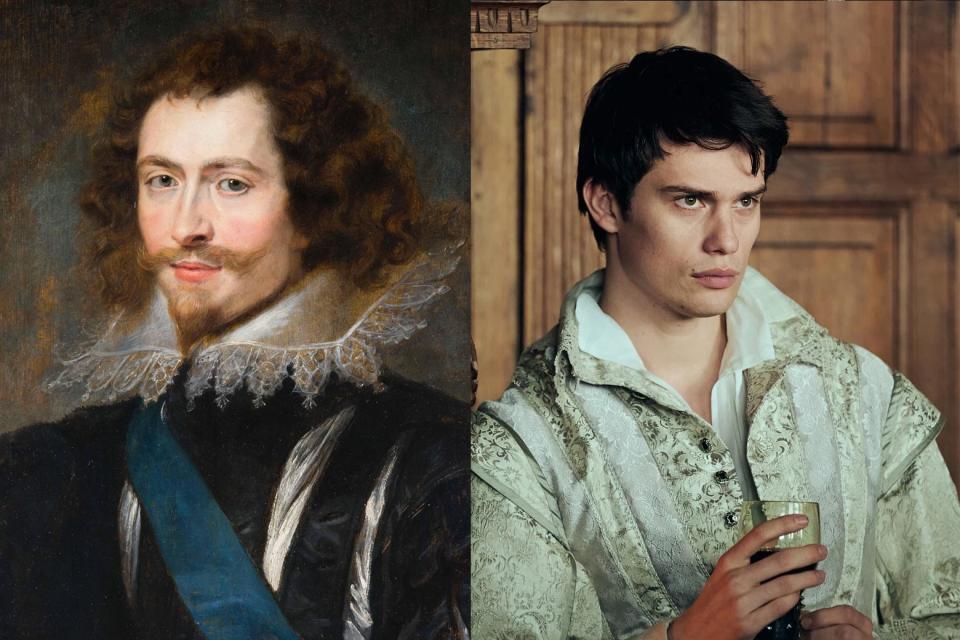

That said, there was a lot of room for dramatic license because, as Benjamin Woolley, the author of the nonfiction book that served as the show’s source material, observed, “We don’t know a great deal about her. We don’t even know when she was born.” The life of her son George, known as “handsomest-bodied man in England” (Nicholas Galitzine, who doesn’t disappoint), is much better documented. Though as you might expect, there were any number of contemporaneous sources ready to repeat scurrilous gossip about a man who rapidly rose from the minor gentry to being the first person not of royal blood to be created a dukedom (the first Duke of Buckingham)—not to mention becoming the most important nonroyal person in Britain, influencing royal marriages, foreign policy, and taking the country to war, all the while amassing a huge personal fortune—based almost entirely on his ability to beguile the king. Here, we explore what’s gossip, what’s invention, and what’s fact in Mary and George.

When, thanks to George’s ascendancy, Mary is finally presented at court, the assembled aristocrats whisper that she started out as a lady’s maid and escaped this lowly position by seducing and marrying her first husband, George Villiers, an abusive country squire. We later learn that although George Villiers paid for papers ostensibly attesting to his wife’s being part of the Beaumonts, an old established family of landed gentry, Mary is being blackmailed by an official who has found papers proving her actual antecedents were undistinguished and that she was originally a servant. (The blackmailer meets a sticky end.)

In truth, Mary was never a lady’s maid, which would have made her a servant, but she was, said Woolley, a “waiting woman” to one of her relatives, a waiting woman being “sort of between service and gentry, so she occupied this rather ambiguous social rank.” A good analogy might be the Victorian “companion,” usually a somewhat impoverished spinster or widow who had no household of her own and was taken in by a more affluent relative to be a sort of personal assistant/dogsbody to the mistress of the house. She would not have dined in the servants’ hall but would not have dined with the family either, inhabiting, like a governess, a social gray zone.

In actuality, Mary was genuinely a Beaumont, and Villiers, her first husband, was a cousin of her mother’s. But although they had a pedigree, the Beaumonts had no real money, so she started out as, if not a servant, a poor relation.

Following Mary’s clever strategic advice, George comes to James I’s attention and takes up residence at court after being appointed a royal cupbearer. Robert Carr, James’ current favorite (despite his being very happily married to Lady Carr), senses competition and seeks to humiliate the newcomer. The relatively naïve George finds himself relegated to playing the cello with a veil over his head in the king’s private apartments as a mostly male orgy is in progress.

No one can say for certain what went on behind closed doors, but from what we know of James, such libertinism seems unlikely. Certainly James was known for a roving eye for beautiful young men, or “Ganymedes,” named after the beautiful youth of Greek mythology who stole the rampantly heterosexual Zeus’ heart. But this might have been fake news circulated to stir up anti-Scottish prejudice (James I of England, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, was simultaneously James VI of Scotland) or resentment toward the favorites. The received view of James was summed up by historian Lawrence Stone, who wrote, “As a hated Scot, James was suspect to the English from the beginning. … Reports of his blatantly homosexual attachments and his alcoholic excesses were diligently spread back to a horrified countryside,” especially since Henry VIII, that model of morality, had made consensual sex between men illegal in 1533.

Much of this reputation for licentiousness was based on diplomatic gossip. In 1618, the Venetian ambassador reported home that “the King honoured [the Duke of Buckingham] with marks of extraordinary affection, patting his face,” while the French ambassador, quoted in Michael Young’s King James and the History of Homosexuality, asserted that he “had too much modesty to report everything” he saw in graphic detail, comparing James’ retreats to the English town of Newmarket with his coterie of Ganymedes to the dissolute Emperor Tiberius’s notorious sojourns on Capri.

While the orgies are dubious, James definitely had intense romantic attachments to three men (of whom Villiers was the last) in his life. There is no doubt that he was deeply in love with Villiers. Another letter from the Venetian ambassador observed that “the King has given [Villiers] all his heart, who will not eat, sup or remain an hour without him and considers him his whole joy,” while a member of Parliament named John Oglander noted he “never yet saw any fond husband make so much or so great dalliance over his beautiful spouse as I have seen King James over his favorites, especially the Duke of Buckingham.”

Moreover, when Villiers was made a privy councillor in 1617 at age 24, James made a speech saying, “You may be sure that I love the Earl of Buckingham more than anyone else,” and later that year sent Villiers a portrait of himself with his heart in his hand along with passionate letters addressing Villiers as his “sweet heart.”

While no definitive proof exists that the relationship was fully sexual, a restoration of James’s residence, Apethorpe Palace, in 2008 revealed a previously unknown passage linking the king’s and Villiers’ bedchambers.

On the other hand, James also wrote a book of advice for his young son in which he condemned sodomy as an unforgivable crime on par with witchcraft and murder. In James’ day, sodomy was seen as a vice that accompanied or grew out of other sins; there was no sense of homosexuality as a component of identity (the term homosexuality wasn’t even introduced until the end of the Victorian era). In the prevailing medical theory of the time, male and female bodies were considered to be fundamentally the same, with sex differences determined by the way bodily “humours” (special fluids, like bile and phlegm) flowed through them. A man wanting sex with another man was thought to have an imbalance in his humours. As for Villiers, his homosexual behavior seems to have been at least in part strategic, since after James’ death he reinvented himself as robustly straight.

In fact, the series’ presentation of James as something of a rough diamond interested mostly in hunting, drinking, and ogling young men, while not exactly wrong, is limited. Besides the aforementioned book of advice, James wrote books on subjects as diverse as the divine right of kings, the evils of witchcraft, and a prescient warning about the harms of tobacco use. He commissioned and sponsored the translation of the Bible into English that is still known as the King James Version and is remarkable for being a work of literature as well as scripture. He was also the patron of the theater company known as the King’s Men, whose resident playwright was one William Shakespeare. No fool, the Bard wrote a play about a Scottish king troubled by the supernatural, with many of the quotes and rituals used by the play’s three witches lifted directly from his patron’s book on the subject.

In the series, James’ queen, Anne of Denmark, is very understanding about the king’s homosexual inclinations and often offers him advice and a shoulder to cry on about his extramarital relationships, seeming more like a big sister than a wife.

This sounds too good to be true, and it is. Initially the royal couple was happy, but a rift opened in 1594 when James, then just King of Scotland, insisted the newborn longed-for heir, Prince Henry, be raised apart from his mother at Stirling Castle. After this, James and Anne led increasingly separate lives at court, where she had to put up with the king’s blatant infatuations with his favorites. The rift was further widened by Anne continuing to worship as a Catholic and surrounding herself with Catholic ladies-in-waiting, despite James’—and most of Scotland’s—staunch Protestantism.

Nevertheless, the couple managed to have seven children, three of whom lived to adulthood. However, after the birth and death of her daughter Sophia in 1607, and resulting gynecological issues, Anne declared she didn’t want any more children and the couple rarely lived together, with Anne preferring to stay in London and the king in more rural residences where he could hunt. However, although James visited Anne only three times during her final illness, he was, as the show suggests, deeply affected by her death.

As his star rises, George gets caught up in the court’s byzantine geopolitics and jostling for power. Originally George is mentored by the scholar and Attorney General Sir Francis Bacon, who wants peace with Spain, but then falls afoul of Bacon’s rival and his brother’s father-in-law Sir Edward Coke, parliamentary leader and cheerleader for war with Spain. Mary advises her son to tell Coke he will testify against Bacon, so George visits the Spanish ambassador and asks for proof that Bacon has been working in Spain’s employ. In return, he offers to persuade James’ son and heir, Charles (Prince Henry having died), to marry the Spanish infanta.

Parliament refuses to agree to this alliance with a Catholic kingdom, so Charles and George decide the best thing to do is go on a surprise unofficial visit to Spain, where the less-than-prepossessing Charles can sweep the infanta off her feet. At a very formal audience at the Spanish court, Charles decides to woo the infanta by singing a sad song to her, and amazingly, it works. The infanta is captivated.

This is not what happened in reality. But you can see why the show’s writers found it easier than the real story, which would have gotten bogged down in the ever-shifting complicated alliances of European royal families, the feuds between different branches of the Habsburg dynasty, the causes of the Thirty Years’ War, and similar weighty matters that would take 40 episodes to explain and lose viewers in droves.

In actuality, Prince Charles and Villiers did travel on their own in 1623 and just turned up uninvited at the Spanish Court, which was a distinct break from protocol. But the chances of a Spanish infanta being allowed to meet a man outside her immediate family was exactly zero and Charles was told he could not pay court to her in person, singing or no. The best he could manage was to catch a glimpse of her while a carriage he and Villiers were traveling in passed by a carriage the infanta and the queen, her sister-in-law, were in. That was it.

Sir Francis Bacon loses his power struggle with Sir Edward Coke after Mary threatens to expose him as a traitor in the pay of Spain. Coke banishes him from court and strips him of his titles. Things get even worse for the former attorney general when his syphilis deteriorates, and shortly before his death he is forced to wear a metal nose to hide the disappearance of his natural one—a consequence of late-stage syphilis attacking cartilage.

In reality, Bacon did not die of syphilis and there is no proof that he had it. His actual cause of death was far more interesting. Together with the king’s physician, he conducted an experiment on whether freezing meat would preserve it as effectively as salting it, and to this end the two men stuffed a chicken with snow. This reportedly resulted in his catching a chill and he died of pneumonia a couple of days later.

As with James, the show presents a not inaccurate but flattened view of Bacon. More than just a political wheeler-dealer, he was one of the preeminent intellectual figures of the English Renaissance. His writings on natural philosophy stressing the importance of closely observing events in nature led to his being considered the father of empiricism and a major influence on the development of the scientific method.

As well as being a member of Parliament, he was a practicing barrister (at one point becoming legal advisor to Elizabeth I and thus the first designated Queen’s Counsel), and his legal writings are thought to have influenced the drafting of the Napoleonic Code, the basis for France’s legal system. He also played a major part in establishing Britain’s colonies in North America, especially Virginia and the Carolinas, and Newfoundland in Canada.

If Mary and George’s creators wanted to inject a note of unexpected scandal into this life of accomplishment, there was no need to invent a fatal dose of a venereal disease. At the age of 45, Bacon married his wife Alice and wrote two sonnets declaring his love for her. She was 13.