What Cormac McCarthy's letters to Knoxville couple say about the famously private author

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Pulitzer Prize-winning author Cormac McCarthy died in 2023, Knoxville residents were quick to reminisce about his deep connections to the city. Many credit McCarthy, whose family moved here in 1937, with introducing Knoxville to the world with the publication of “Suttree” in 1979.

A number of local spots pay homage to McCarthy, but he was famously private and rarely granted interviews. So any chance to catch a glimpse of the author as a person are highly valued by both fans and scholars.

And that’s why the recent sale of personal letters and photos tying McCarthy to Knoxville, along with one of only two final-copy typescripts of "No Country For Old Men" known to exist, garnered an enormous amount of interest.

The signed typescript in question, along with most of the previously unknown archive of McCarthy letters, photographs, postcards and other ephemera, originally was headed for sale at theABAA New York International Antiquarian Book Fair this April.

The items didn't last that long on the open market, however. Most of the correspondence was snapped up by the Southwestern Writers Collection/Wittliff Collections at Texas State University, one of the largest collections in the country documenting McCarthy's entire writing career.

What was in the collection of Cormac McCarthy materials?

The archive was marketed by Stuart Lutz, who specializes in the correspondence of "household famous" people, such as the presidents, Revolutionary War and Civil War figures, famous writers and important scientists. Lutz might be familiar to fans of "Pawn Stars," where he appears as a historic document expert.

Lutz became involved, he said, because he does a lot of authentications for John Case of Case Antiques. Case had been appraising the collection for Knox County resident Lanelle Holley; Lanelle and her late husband, John, had been friends with McCarthy dating back to the early 1960s.

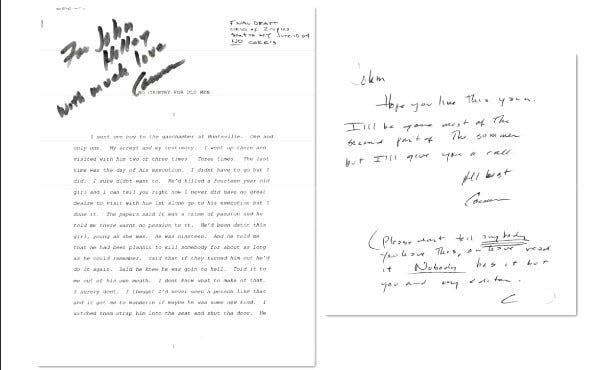

Lutz described the items for sale as including the typescript for "No Country for Old Men," marked “FINAL DRAFT ORIG of 2 copies” and with a brief note in black marker on the front cover: “For John Holley with much love Cormac." It was accompanied by a letter to John Holley that reads, “John Hope you like this yarn. I’ll be gone most of the second part of the summer but I’ll give you a call. All best Cormac (Please don’t tell anybody you have this, or have read it. Nobody has it but you and my editor. C."

The lot also included typescripts of "The Gardener's Son," a screenplay written by McCarthy in 1977 that was published as a book in 1996, and "Cities of the Plain," the final volume of the Border Trilogy published in 1998.

The letters to the Holleys were valuable because McCarthy "kept his circle small," Lutz said, adding, "He had a limited number of people he corresponded with over the years. One thing about this archive, it shows that he never forgot the Holleys ... Even as he got bigger and wealthier, he never forgot them, it says a lot."

How were John and Lanelle Holley connected to Cormac McCarthy?

When Lanelle met John Holley in 1963, the two men were friends already. But McCarthy became an integral part of the couple's life from the get-go; he was there the night John proposed to Lanelle after a whirlwind courtship

And an impulsive decision to have McCarthy spend that Christmas with them cemented the connection.

"He was living in Wears Valley and we were just sitting there on Christmas Eve about 11 o'clock and John said, 'I wonder what Cormac is doing for Christmas,'" Lanelle said, adding the couple was living in Asheville at the time. "So we left North Carolina and drove across the mountains with snow over the side of the car. We got there, oh, sometime around two-ish, I guess, and he was up. We picked him up and brought him back home."

McCarthy ended up living with the Holleys for at least a few months.

"He was such a delight to have around you," Lanelle said. "He's not somebody that you wish (would leave). ... It seemed perfectly normal. Cormac was so easy (to be around). And so pleasant, and happy."

The genesis of a writing life

In those early years, McCarthy came to stay on more than one occasion, Lanelle said, adding this was long before he was considered a "writer." McCarthy's first novel, "The Orchard Keeper," was published in 1965.

"Nothing had happened at that point," she said, adding that McCarthy would sometimes disappear for days while he was writing. "But he was writing and it was striking because at first you think, is this just something that he wants to happen? Or is he really serious about this? ... And then as it kept getting a little stronger with the writing, (we knew) that he was very serious about it. It was just supposed to happen."

When Lanelle first started reading McCarthy’s work, she wasn’t sure how the writing, which she called "a little dark," would be received."They were so different that I thought oh, my goodness, are they all like this?" she recalled. "But then you were reading and you didn't put him down. ... We knew after about the third book that this was for real, this is something he would be doing, even though they weren't like everybody else's books."

McCarthy rarely granted interviews, not concerned with fame

Up until 1991, none of McCarthy's novels had sold more than 5,000 hardcover copies. He did not win widespread recognition until "All the Pretty Horses" became a New York Times bestseller in 1992, selling 190,000 hardcover copies within six months.

The Holleys were taken aback when their longtime friend became a celebrity, Lanelle said.

‘We will never see his like again’: Remembering Cormac McCarthy beyond his bleak novels

"My daughter came in and said, 'I found Cormac on the internet,'" she said. "I said, 'No, I don't think so.' She got really upset with me for not believing her and she brought her phone in and showed me his picture."

Excited, Lanelle called McCarthy and asked him if he had seen the article online. His response?

"He said, 'Honey, I don't have a computer," she said with a laugh. "He didn't even have a cell phone at the time. ... He just had no idea of the amount of books that were being written about him and about what (his) ideas were about, all the people that were just eating up every word … He couldn't care less. That wasn't his mission."

'I can still have all my memories'

McCarthy continued to keep in touch with the Holleys over the years, getting together with John several times. But even when they didn’t see each other, she said, they talked frequently on the phone. John Holley died in 2015.

After McCarthy died in 2023, friends "strongly suggested" she should get all the letters, typescripts and signed books insured and appraised, Lanelle said.

During that process, John Case suggested she auction some of the collection off.

"That’s what I decided to do," she said. "I kept a few things to be able to look at occasionally − but I can still have all my memories."

Why did Texas State want the Cormac McCarthy archive?

The Southwestern Writers Collection/Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos holds several Cormac McCarthy-related collections that contain almost 100 boxes and include research, notes, hand-written and typed drafts, correspondence and other materials documenting McCarthy’s career.

The Southwestern Writers Collection acquired the bulk of its McCarthy papers in December 2007; the collection documents McCarthy's entire writing career including correspondence, notes, handwritten and typed drafts, setting copies and proofs of his novels.

The acquisition of the papers was the work of founding donor Bill Witliff, said The Witliff Collections Director David Coleman.

As he tells the story, Wittliff was involved in the Sundance Film Festival and read a script McCarthy had submitted, a piece that eventually formed the basis of "Cities of the Plain."

Wittliff wrote a note to McCarthy that said, "We're going to pass on this as a script, but you are an amazing writer." And that started a correspondence and friendship, Coleman said, adding that over the years Wittliff would send McCarthy the occasional note telling him he wanted to house his archives.

When it finally came to pass, the director said, it was "a huge coup for us."

Snapshots, casual notes prove invaluable to Cormac McCarthy scholars

Texas State opted to purchase only the more personal items from the Holley archive, Coleman said.

"We got a small collection of postcards and notes from Cormac to them, they're very sweet," he said. "And then there's a little plastic photo album with snapshots, color and black and white, from the '60s to I guess the '80s. They are nice to have − the world hasn't seen a whole lot of photos of Cormac from his personal life."

Coleman called The Witliff Collections "the center" of McCarthy research, adding, "We're excited to acquire something like this. We know our researchers will love to look through these materials."

McCarthy, Coleman explained, has a reputation of having been somewhat of a recluse. And that's what makes his correspondence with the Holleys so special to an archivist.

"I think what you see is that (reputation) is really in regards to the press and not to his friends," Coleman said. "He had a lot of friends, he was interested in 1,001 topics and could talk about anything. He was very sociable with his friends."

McCarthy avoided interviews because, said Coleman, he really didn't like talking about his work. And that was true across the board.

"I've talked to people who met Cormac, and soon as anyone would bring up a character or a book, that would be the end of it," he said. "Not in a rude way, but it would stop the conversation."

It is always interesting to find out about a famous writer's personal life, Coleman explained, even with seemingly mundane correspondence. The Holleys' notes are valuable because they show a real piece of McCarthy's personality.

"It shows him as a normal person, not a writer," he said of the letters. "He even sent John a note saying something like, here's a passage about horses, I'd love to hear your thoughts on it − don't hold back your critique."

That happened while McCarthy was writing the "Border" trilogy, Lanelle Holley said.

McCarthy always "wanted to make things as accurate as absolutely possible," she explained, adding, "My husband used to be in rodeos and just knew what could and couldn't be done. So those three books, Cormac either sent him a copy or a manuscript and he (would say), 'Read this for me and tell me if all this is feasible.' And so he would read it and would circle things that couldn't be done and say, you know, you wouldn't do this."

Liz Kellar is a Tennessee Connect reporter. Email liz.kellar@knoxnews.com.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: What Cormac McCarthy's letters to Knoxville couple say about author