What Clarkson’s Farm teaches us about male friendship

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Behind the sensational headlines of Clarkson’s Farm, lies a quieter but no-less-riveting tale. The friendships Jeremy Clarkson has made on his Oxfordshire estate have brought out some hitherto unseen qualities in the 64-year-old. Whereas Clarkson’s friendship with his Grand Tour co-presenters James May and Richard Hammond can feel like a power struggle between three spoilt delinquents from a luxury borstal, Clarkson’s relationship with farming partner Kaleb Cooper offers a slow-burning tale of two very different men happy in each other’s company.

The shtick between Cooper and Clarkson is highly comic and reminiscent of Shakespeare. As Prince Hal says of his attempt to humiliate Falstaff with an elaborate prank, “It would be argument for a week, laughter for a month, and a good jest for ever.” Down on the farm you will also find mockery, comic hyperbole and pratfalls.

This state of male arrested development has been explored with varying degrees of subtlety in films as diverse as The Hangover, The World’s End, American Pie and This is Spinal Tap. Essential to the template is the fact that women are unwelcome (unless it is for one specific purpose). The received wisdom is that women can obstruct male friendship or even – with marriage – bring about its demise.

You can trace this back to Jerome K Jerome’s 1889 comic novel Three Men in a Boat which, while lacking the overt vulgarity of its descendants, revels in the idea of male friends needing to get away from it all. Here we have three middle-class gentlemen cavorting up the Thames, freed from the shackles of Victorian London life.

Another thing common to all of the above is that they exist in spaces devoid of emotional connection. But is this because men are bad at intimacy, or because that’s what they actually want?

Certainly, the idea of the “gang” suggests the latter – a large group where the scope for deep and meaningful connections is scarce. And yet, if we look at entertainment and literature, the idea of the gang often reveals a more noble purpose. For example, there are the nine friends who make up The Fellowship of the Ring from JRR Tolkien’s lore and the seven disparate warriors from Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 film The Seven Samurai. “I’m with you,” says Gorobei, one of the Seven, to their leader Kambei. “But although I understand why you would take up the farmers’ cause, it’s your character that I find most compelling. In life one finds friends in the strangest places.”

This is echoed in countless war, fantasy and science-fiction films and TV shows, from The Deer Hunter to The A-Team. The stories gain their pathos through the gradual erosion of the group, as one member after another is lost or sacrifices himself for the others. In this version of male friendship, the affection grows as the group moves on; the bonds tighten as they suffer. The gang also provides the space for different types of men to feel a sense of belonging so that each can provide something unique: the natural leader; the strong, silent one; the joker; the apprentice; the rebel.

The most powerful and enduring male friendship of all is the love affair, in which two men – usually of opposite character and social class – form a bond akin to marriage. This is an ancient archetype that can be traced back to David and Jonathan in the Old Testament and Achilles and Patroclus in The Iliad. While neither relationship is depicted as anything other than platonic, modern readings always stress their homoerotic nature.

The dominant friend with the loyal companion is constantly explored in literature – from the complex Hamlet and down-to-earth Horatio to David Copperfield idolising the Byronic Steerforth to the thousand iterations of Holmes and Watson. Meanwhile, the criminally underrated 1976 film Robin and Marian explores this co-dependency as friends grow old, with the ever-loyal Little John clinging to Robin Hood’s side: part manservant, part bodyguard, part emotional support.

Sometimes, friends are forced together by necessity or they drift apart when circumstances change. Sometimes they are kept together by failure or separated by success. In Alexander Payne’s sublime 2005 film Sideways, Miles and Jack are united, in their male menopausal angst, by what they have not achieved. In the BBC sitcom Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads? (1973-74), writers Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais returned to the characters of Bob and Terry seven years on, to explore how class and social mobility in Gateshead were straining their lifelong friendship. In the earlier series, Bob and Terry’s relationship had represented the working-class aspirations of the mid-1960s, but by the 1970s things had changed – with conflict arising from the values of staunchly unreconstructed Terry versus the socially ambitious Bob.

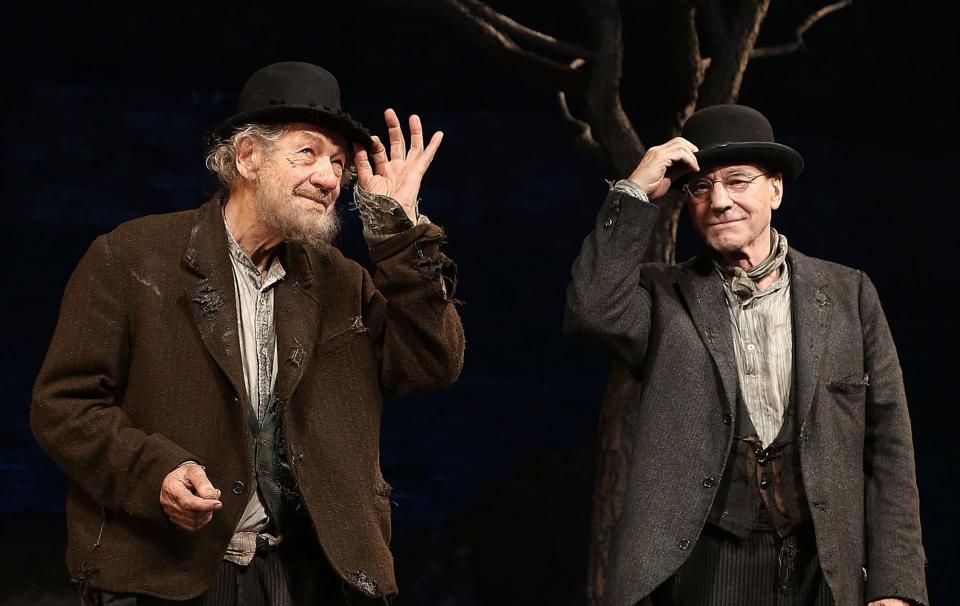

With male friendship comes comfort and safety, but sometimes constraint. As Blake writes in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship.” In Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, such intensity becomes a grim addiction, with Vladimir and Estragon bound to each other in perpetuity while wishing they were not. The underlying truth here is that men need each other, despite trying to maintain the pretence of isolation.

Reflecting on my own experience of male friendship, I recognise all the above varieties. I know men who hold on to their manchild co-conspirators as a way of periodically escaping the realities of adulthood. But being in a gang rarely survives families and middle age, nor does the platonic love affair, which requires a singular focus. What remains is a group of survivors, no longer seeking the thrills of youth, and questing instead for honesty and unconditional support. A happy few indeed, if you’re lucky.

Such support is well illustrated by the BBC’s surprise hit Mortimer & Whitehouse: Gone Fishing, with the humour of Bob Mortimer and Paul Whitehouse channelled through a shared awareness of recent health scares. The kinship is partly one of dread. The programme’s elegiac quality, as if we were seeing The Wind in the Willows’ Ratty and Mole in their dotage, comes from the sense of time passing.

What Gone Fishing achieves, and what Clarkson’s Farm aspires to, is that ultimate goal of all male friendship – simply to be at ease with someone.

Clarkson’s Farm 3 starts is on Amazon Prime Video now