How the Barbour Jacket Has Stayed a Must-Own for Over a Century

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On a cool summer morning in South Shields, England, Barbour factory workers are beginning the approximately 650 jackets they complete in a day. At the start of the production line, a man named Gary cuts lengths of waxed cloth; a woman named Mary cuts pattern linings. Every worker gets a specific uniform color—machinists in green, supervisors in blue, quality control in purple—and they sit in rows, school photos of their children taped to the arms of sewing machines, as the disembodied yet recognizable elements of a Barbour jacket proceed down a modest assembly line.

Each jacket represents five archetypes: fishermen, hunters, motorcyclists, soldiers, and the people who wish to look like them. By the time one garment is finished, it has been touched by dozens of hands and holds 125 years of history. As Barbour prepares to commemorate its quasquicentennial, those who make and wear the brand reflect on the way this family business still resonates all over the world.

For 50 years, the company has been run by Dame Margaret Barbour, whose husband, John, passed away suddenly in 1968 from a brain aneurysm at only 29. On her watch, Dame Margaret introduced an evolution of the Barbour line that elevated its pieces from staples to symbols of style. She designed the now-classic Bedale and Beaufort jackets in the 1980s, streamlined outerwear that became essential to the trendsetters of the era, known as Sloane Rangers. (Think Princess Diana striding through the British countryside.) Icons like Steve McQueen, James Bond, and Kate Moss are closely associated with the Barbour jacket. Together they create a unified theory of casually contradictory Western elegance: royalty prized for seeming, somehow, ordinary and ordained.

Now Dame Margaret is looking ahead to when her daughter, Helen Barbour, as vice-chair, will step into her role. As a member of the fifth generation of the Barbour family, Helen describes the work she does as being both inherited and intuitive. After a lifetime of watching her mother, she has a sixth sense for what is or isn’t Barbour; putting it into words would require language too simple for the complicated interweaving of family and commerce. “The whole development of the business has been organic,” she explains in the boardroom that sits above the factory. “Obviously we look at trends, but it still has a foot in the original Barbour camp. You’ve got to stick with what you know—the loyal customers like what it’s all about, what it stands for.”

The man responsible for balancing the expectations for the brand with an unstoppable fashion cycle is Ian Bergin, the director of men’s wear. He studied politics in school and briefly worked as an electrician before falling into fashion. His role involves pulling from the archive of Barbour jackets and thinking about how customers today cross-reference the company’s history against their contemporary needs. In his studio, Bergin keeps uniforms worn by officers during World War II. They were customized based on personal preference, with insignia showing their rank hidden from the view of aerial gunners. To touch these materials is to remember a time when military apparel was intended for humans, not machines.

It’s clear that Barbour considers its merchandise to be good jackets for good people. An internal company newsletter left on the reception desk, for example, proudly displays the statistic that 50 percent of all Barbour owners are also dog owners. The brand holds three royal warrants, esteemed marks of quality; Prince Charles gave his in large part because of Barbour’s dedication to sustainability. The Barbour Foundation was created in 1988 by Dame Margaret, and the company reports that since then, $25 million has been donated to mostly local cultural, community, and charitable organizations.

In the back corner of the factory, the production line becomes the repair department. Around 14,000 jackets are sent back every year, and an additional 11,000 are restored by customer-service stations in North America and Asia. Barbour customers try to keep their jackets for life, going to great lengths to do so. Company policy states that two hours is the maximum length of time for a repair. If it’ll take longer, a new jacket is recommended, though exceptions are often made for silly or sentimental reasons. The head of repairs is named Donna, and she delights in the sometimes absurd nature of requests. On the day of my visit, she holds up a jacket that had been shredded by a very small animal, then shows me the photo that accompanied it: a forlorn puppy sitting beside a handwritten note reading, “I’m sorry, the wax tasted too good.” One man asked the company to preserve his jacket for another generation, sending photos explaining that he once carried his baby daughter in the side pocket and now does the same with his granddaughter. (The company inspires even more pocket-centric lore, including the refrain that the back pocket of the Beaufort is for storing game and the side pocket of the Bedale fits a bottle of Champagne.)

Whereas some customers hold on to their vintage jackets for as long as they can, others are introduced to the brand at a cultural inflection point: The 2007 Glastonbury Festival, at which bold-faced names like Lily Allen, Arctic Monkeys, and Alexa Chung wore their jackets as a shield against rain and mud, was one such moment, while blockbuster films have provided more. When Helen Mirren sported a Beaufort jacket in costume as Elizabeth II in The Queen (2006), sales doubled. When Daniel Craig played James Bond in 2012’s Skyfall, he wore a sports jacket made in collaboration with Japanese designer Tokihito Yoshida. Online Hypebeast communities lost their minds, and seven years later, used versions of the jacket have fetched prices over $350.

There is a magical-thinking quality to being a Barbour person. Bergin suggests that the brand is beloved because it is all about a “classless” item, an imaginary concept—it’s true anyone can buy a Barbour jacket, but a king in his Barbour is still king. Customers choose Barbour out of their collected desire to live in what they view as a better world, and to look like what they believe is a better person. This harmonious vision sweeps far past the horizon of current Barbour owners. I ask Helen and Bergin what they would say to a person who has never worn a Barbour jacket. “Is there someone in the whole world?” Helen asks, not entirely rhetorically. “I would say you’re mad. You need one. You must live somewhere where it never rains,” she responds practically. Bergin looks at it more philosophically. “A beacon of consistency in a world gone mad, especially at the moment,” he says, “it’s an old friend.” He pauses for a second. “Did Helen say something similar?”

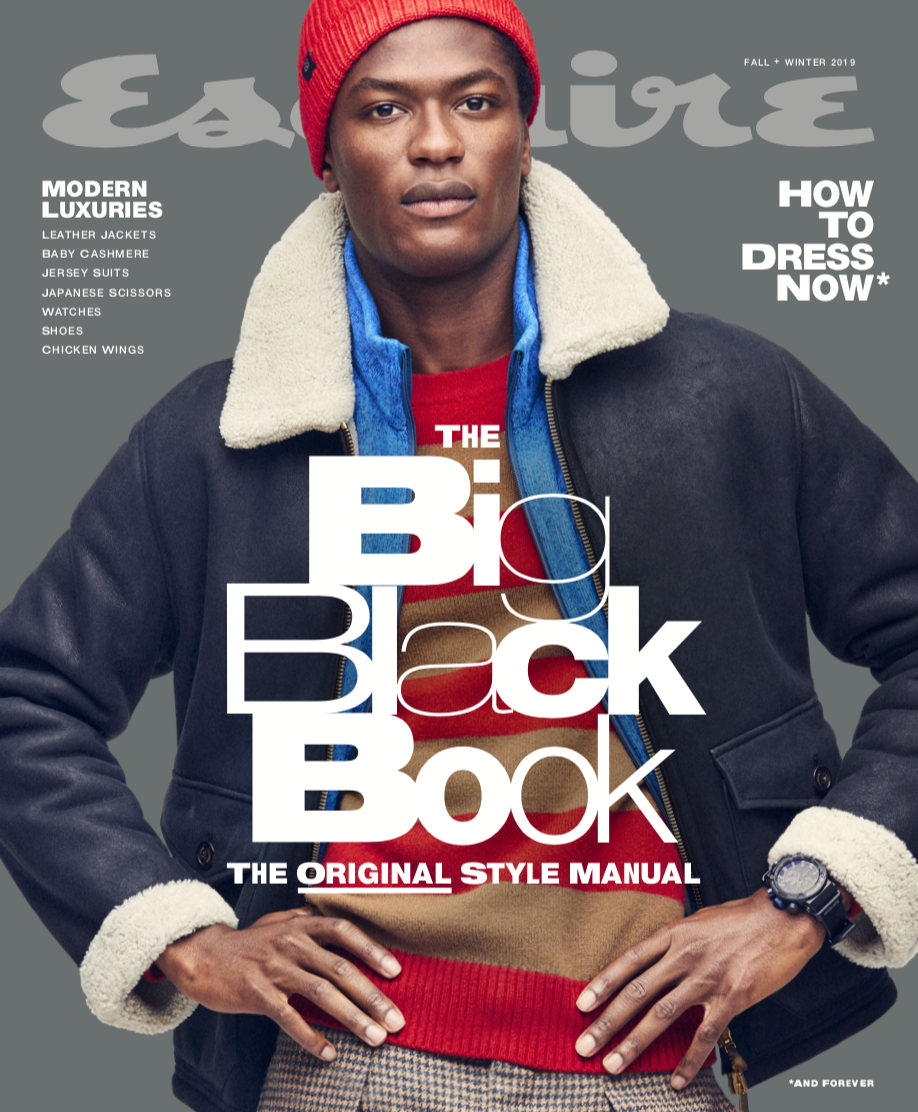

This article appears in the Fall/Winter 2019 Big Black Book

Fall/Winter Big Black Book

buysub.com

$12.99

Allie HollowayYou Might Also Like