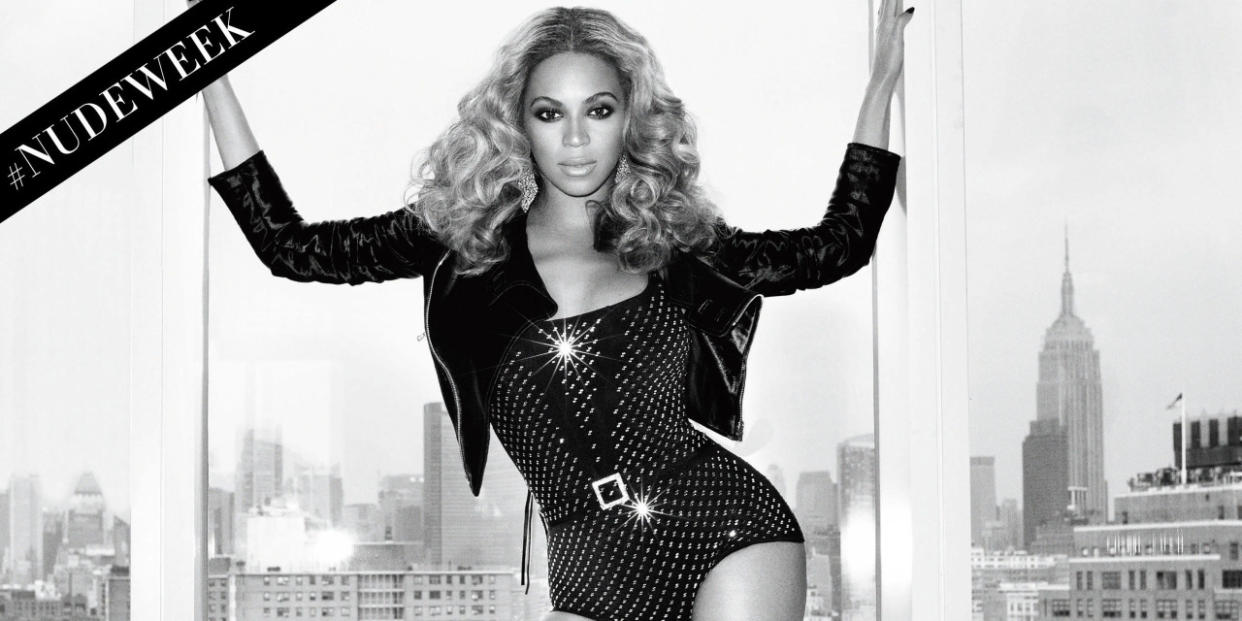

Just Because I'm Black Doesn't Mean I Want to Look Like Beyonce

When I see my naked body, I’m unable to hide. I have to face myself head-on to really see myself clearly: my dark skin and my kinky hair, my wide nose and hips, my tattooed arm and my dark eyes. I’m used to seeing these parts of myself in a certain light, as something separate from myself-something that others see, but I don’t own. I’m used to seeing my body through the eyes of my lovers, through the eyes of my peers, my parents-but most of all, through the eyes of a society that expects me to look like, and feel as good in my “fierce” skin as, Beyoncé. But I don’t.

As a black woman, I’ve always been aware of my race before my gender. It started subtlety at first: the difficulty in finding make-up that would actually show up on my skin, the self-consciousness of not being “black enough” for the black kids, but too black for anyone else. If I wanted to fit in, I needed to learn how to navigate accordingly. I needed to learn how to assimilate my looks. Instead, overwhelmed and dejected, I chose to mentally opt out. I refused to partake in it at all.

The idea of beauty has always confused and intimidated me, mostly because body image is complicated for black women to discuss. The archetype of our bodies-fierce, strong and powerful-has been objectified and fetishized for decades, but it comes at a price. Famous women that “look like” me, with the same dark skin and “different” features, are seen as dramatic objects, desired for their tough rapper or celebrity status. But this body ideal never felt like mine. Rather, it felt like a sense of rejection. I felt excluded from what is considered black woman attractiveness.

“The archetype of our bodies-fierce, strong and powerful-has been objectified and fetishized for decades, but it comes at a price.”

I looked for answers, but only received discouraging ones. If I didn’t fit into this black woman beauty ideal, I needed to be as close to Eurocentric beauty as possible: fair-skinned, pouty-lipped, and curvy in only the acceptable places. So I was left at an impossible crossroad-I wanted to be attractive but I didn’t want to be punished for not fitting into whatever box others chose for me. I wanted to feel that sense of power that I saw in other black women-like Beyoncé, Nicki Minaj, and Rhianna-but trying to exist in the space between mammy and Jezebel was exhausting.

Then I would see white women take on cornrows, unnaturally full lips and full hips and I couldn’t help but feel commodified-an object to pick apart. They get to choose what they like best about us and leave the rest at the wayside.

I thought that opting out altogether showed that I was superior to this need to feel beautiful. But I slowly learned it just promoted an unhealthy sense of false empowerment. Yes, these A-list black women are lauded for their “bad ass” archetype, their staunch physique, their “don’t fuck with me” beauty. But that shouldn’t negate my own. This was the hardest lesson to learn.

So I started slowly. I set out to find a femininity that I could claim as my own. I scoured thrift store racks to find unique pieces that looked (and sometimes smelled) like things I’d seen in old movies or my imagination; things Beyoncé would never wear, but that I loved. Then, once my confidence grew, so did the boldness with how I wanted to look.

My moment of real rebellion came when I decided to cut off my long, straightened hair. For black women, our hair is the ultimate accessory, and often our biggest tool of assimilation-one of the few parts of Eurocentric beauty we can participate in, with the variety of hairstyles it affords us. But for me to fully reclaim my own version-and vision-of beauty, I needed to reject it completely. My new short hair was a promise to myself that I was no longer hiding behind something I thought I had to be. I committed to only being myself.

Terrified, I watched the strands fall to the ground, giving birth to tight curls barely a centimeter above my scalp. I looked in the mirror and immediately felt a sense of peace. I thought, Yes. This is who I’m meant to be.

Finally able to see myself away from the gaze of others, I have been able to reclaim my feminine body as beautiful. I can exist as far from the margins of expectation and stereotypical black beauty as I choose. I have learned that beauty, like anything else, exists for myself before anyone else. This doesn’t make me immune to the daily struggles of being a black woman, but it injects much-needed tranquility into my life.

My naked self may not be everyone’s idea of beauty, but to finally feel good looking in the mirror is just as empowering as I imagined it to be.