Time Poverty Is The Health Issue We’re Not Paying Attention To But Should Be

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Much ink has been spilled on how we all have the same 24 hours in a day, the only difference being how we choose to use them. “Saying you don’t have time is the adult version of saying your dog ate your homework,” one quote widely shared on Facebook reads. Other posts remind us, “Yes, you’re busy, we all are. Don’t be a drama queen and just do it.” The takeaway? Making the most of your time is how you get where you want to go. In this way of thinking, the key to unlocking the age-old dilemma is simply prioritization.

Thing is, we don’t all have the same amount of free time to begin with. Time, like money, is something certain people have more of than others. Every spare minute affords basic human rights and privileges, making excess hours a luxury and rendering a portion of the population “time poor.”

To clarify, time poverty is the subjective experience of having too much to do and not enough time in the day to do it, says Ashley Whillans, PhD, author of Time Smart: How to Reclaim Your Time and Live a Happier Life. You may experience this if you’re consistently working late or if you have children. Add in laundry, grocery shopping, paperwork, and any emergencies, and your already limited discretionary time can quickly dwindle to nothing.

This juggling act of priorities likely sounds familiar.

But women, who take on the majority of unpaid labor at home and often end up the default parent, are among those with the most balls in the air, per a recent study in the Journal of Global Health. “In many ways, women are the ones who will cut back work hours, or even pull out of the labor force,” says Liana Sayer, PhD, director of the Maryland Time Use Laboratory. “Or they’ll simply try and do both a paid job and their unpaid labor, leaving less time for leisure and sleep.”

The pandemic only exacerbated these existing issues, leading nearly 3 million women to leave the workforce as of February 2021. While some women reaped the benefits of work from home, 80 percent of those surveyed in Deloitte Global’s 2021 report, Women @ Work: A Global Outlook, said their workloads increased due to the pandemic, and nearly half adapted their working hours to accommodate increased caregiving duties, which hampered their relationship with their employer.

When inadequate wages are associated with race and ethnicity, it usually means heavier time burdens.

Low-income women of color face the steepest pay gap, which ends up fracturing their time and complicating their paid and social roles. “Because so many women of color work [shift] occupations, like warehouse or care work, and have to be available at odd times…the hours for anything else are taken away,” says Angela Glover Blackwell, founder-in-residence at PolicyLink, a research and action institute for racial and economic equity. “They’re starved for the time it takes to invest in relationships with family or community.”

These women may hope to fit in a parent-teacher conference, but when paid time off isn’t guaranteed and shift assignments are announced the day before, to-do lists end up looking more like wish lists.

Black women bear the brunt of time poverty, as 68.3 percent are their family’s primary financial support, per the Center for American Progress. That’s more than double the percentage of white women and over 50 percent more than Hispanic women. Even at home, relaxation time can be a rarity when you’re busy cooking meals and helping with homework.

What’s more, 21 percent of Black female-headed households didn’t have access to a vehicle in 2017, per the National Equity Atlas—meaning precious minutes are spent on public transportation. The goal for this demographic? Survival. The grit and productivity of “hustle culture” celebrated in other circles is, in their case, just a means to get by.

The more you consider the time required to get and stay above the poverty line, the more apparent the effect on well-being becomes.

Those struggling most to make ends meet often don’t have time for self-care. They’re unable to schedule routine doctor’s checkups, to exercise, or to adequately address their mental health. Even nutritious dinners rarely make the cut. Women who work multiple jobs to earn a living wage are often left to rely on fast-food joints, since grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods may be few and far between. Even if they do find time to stock their pantries, buying in bulk is out of the question unless they have a car or access to one.

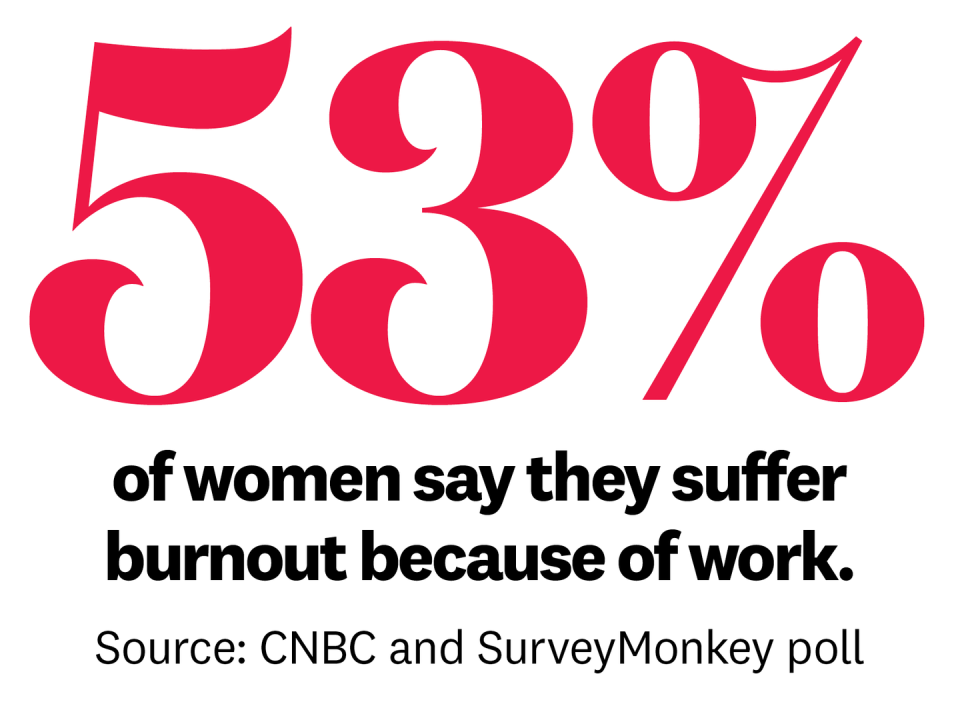

You can see how the well-meaning suggestions to lean on friends when you’re weary, get more sleep, and keep healthy snacks on hand just aren’t options here. “Time stress has a stronger negative effect on happiness than being unemployed,” Whillans adds. It also ups the risk for cardiovascular disease, higher BMI, and depression, according to research.

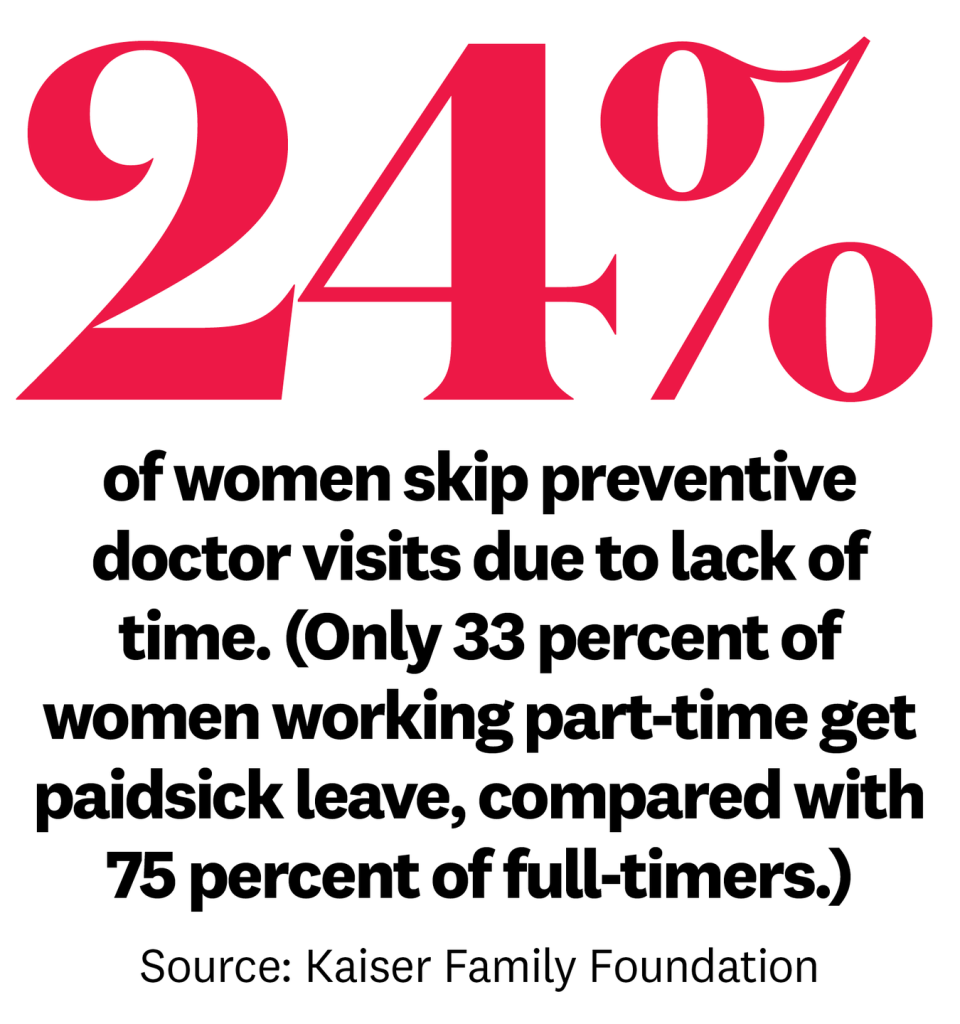

When women do find a moment to prioritize well-being? It’s usually not their own: Seventy-seven percent of mothers took their children to doctor’s appointments, compared with one-fifth of fathers, per a survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation. For those without access to paid sick leave, a check-up may not even be in the cards.

Upping time-management savvy or "hustling harder" to focus on what and who you love would do little to mitigate time poverty.

The issue calls for systemic restructuring—changes in the status quo. “One of the key factors perpetuating the cycle of poverty is not just material constraints, but also temporal constraints,” says Whillans. In other words, poverty won’t be adequately addressed until policy makers and organization leaders acknowledge it’s caused by both financial and time inequality.

One solution, offered by Saru Jayaraman, director of the Food Labor Research Center at UC Berkeley and president of One Fair Wage: Raise the minimum wage. It’s something, she says, Congress could do this year.

“The restaurant industry is the largest employer of women and women of color in the US—nearly 14 million workers,” Jayaraman offers as an example. “The very simple step of raising their wages from $2 to $15 dollars an hour with tips on top would allow them to not have to work two or three jobs. It would allow them to spend time with their children, not just provide quick food on the table.”

Quality of work must be considered, too. “Being able to have predictable hours, sick leave, and family leave, and being able to take off in an emergency are vital,” says Glover Blackwell. As is having a voice to speak out about workplace conditions.

If ever there was a time to reflect on the detriments of being time-poor, it’s at the tail end of a devastating pandemic, when time felt precious yet full of risk. Jayaraman notes 2020 headlines about women who had the opportunity to spend more time with family, to focus on hobbies they’d been neglecting, and come to the realization that their work-life balance was non-existent and so chose to leave their jobs.

For millions of Americans, she says, those options aren’t on the table. Instead, low-income women whose businesses couldn’t offer work from home options or were shuttered altogether, spent hundreds of hours calling unemployment agencies in the hopes that their next 24 hours might be better than the last.

Even if you haven’t experienced this issue yourself, knowing your access to the resource differs from others’ can help you see why your list of musts likely differs too. (Often, it’s not so much the choices you make, but the circumstances you live in.) So, consider this mind-blow moment the first step to changing everything—for yourself and others.

You Might Also Like