Socialism played a prominent role in Oklahoma politics more than a century ago

Use the word socialism in the last decade, and you’ll likely conjure images of political ads claiming takeover of the United States by the country’s “coastal elites.”

But from the turn of the 20th century through the end of the World War I, socialism was commonplace throughout much of the country, including finding a substantial support system among Oklahomans.

“Proportionally it (Oklahoma) was the largest Socialist Party given the small population of the state. It had more dues-paying members than New York State at its height,” said Stephen Norwood, history professor at the University of Oklahoma. “At its peak strength, the Oklahoma Socialist Party could pull close to a third of the vote.”

The rise of socialism in Oklahoma

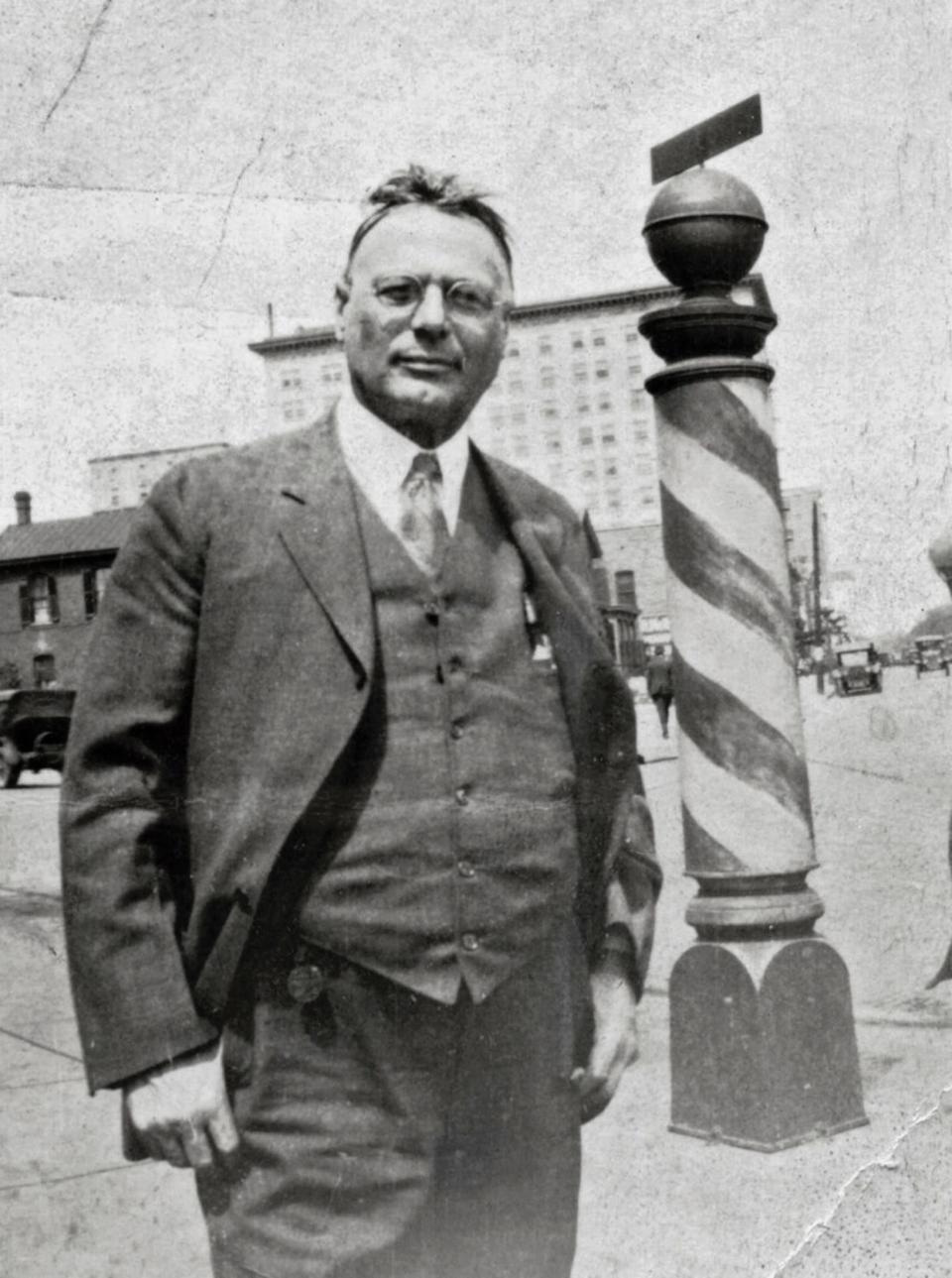

East Coast and Midwestern cities led much of the early socialist movements where the focus fell on those workers in industrialized areas. However leaders of the movement like Oscar Ameringer soon saw an opportunity among those living in rural areas of the country, as well.

“When Ameringer came to Oklahoma in 1907, he realized looking around that you could not build a socialist movement on the traditional socialist base,” Norwood said. “There wasn't much industry in Oklahoma."

More: All but one of Oklahoma City's 2022 mayoral candidates file final contribution reports

Ameringer, originally from Germany, first found his way into organizing with labor movements in Ohio and Louisiana before moving to Oklahoma to work in the Socialist Party. Instead of focusing on the traditional views driven by Marx’s writings and the belief that industrial workers would lead the movement, what Ameringer found in Oklahoma was an impoverished state made up of largely agricultural workers. Many of those workers were tenant farmers who did not own the land on which they worked.

Norwood said after the Land Run, much of the land in the state ended up in the hands of coal companies, oil companies, railroad companies and other wealthy landowners, leaving small farmers no choice but to rent from them.

“That meant that if you're in that situation, you don't have any real hope for a future. You'll be living in poverty generation after generation like sharecroppers in the South,” he said. “The socialists provided some hope for these people."

An early Ameringer meeting took place in Harrah, Norwood said, as he began traveling across the state sharing the socialist platform and message. Norwood said Ameringer describes this meeting in his autobiography.

"He notices that the man who greeted him and was going to introduce him to the audience was really soaked to the skin, and he asked him why that was,” Norwood said. “There had been a torrential downpour, the sort that we often have in Oklahoma, and the bridges had been washed out but he wasn't going to miss the opportunity to introduce Oscar Ameringer so he swam across the river.”

More: Social issues at forefront of Oklahoma state superintendent race

Ameringer was impressed by the dedication of the farmers who were living at little more than a subsistence level. However, in addition to changing their message and leaning away from some of the stronger Marxist ideals, the socialists also had to lean into religion for the poor rural populations of Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas, rather than denouncing it as other socialists throughout the country did.

“They used religious imagery,” Norwood said. “People come from all around in their wagons, or on horseback or on foot and they're used to listening to ministers preaching, so the socialist orders would adopt the same kind of — almost a fire and brimstone, apocalyptic style — in presenting the socialist message.”

The goals of Oklahoma’s socialists

Norwood said unlike the National Socialist Party, Oklahoma’s socialists did not advocate for the traditional ideal of publicly owned resources, often seen as being on the left-wing of the party or the part of socialism known as red due to its affiliation with Marxist ideals.

“Now in Oklahoma, that's not going to work. If you make that your message, you're not going to get anywhere; you have to be more flexible,” he said. “What they proposed was taking the big landholdings and dividing them into small farms that would be individually owned private farms.”

Candidates representing Oklahoma’s Socialist Party often polled close to a third of the statewide vote in elections. Ameringer himself would capture about 23% of the vote in the 1911 race for mayor of Oklahoma City.

In the 1914 gubernatorial elections, Fred W. Holt received 41% and 35% of the vote in Marshall and Roger Mills counties, respectively, where socialism was strongest, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Socialism falls out of favor

In 1917 at the height of World War I, a group of tenant farmers in Oklahoma staged a revolt along the banks of the South Canadian River. This uprising, known as the Green Corn Rebellion, was in protest of the country’s forced draft or conscription policy.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, “men planned to march to Washington and end the war, surviving on the way by eating barbecued beef and roasted green corn, the latter giving the rebellion its name.”

“It didn't get very far, and it was suppressed — posses were quickly recruited — and went after these armed men and suppressed the uprising,” Norwood said. “But the green corn rebels did seize some banks and county offices.”

More: Oklahoma GOP Congressional candidate John Bennett calls for execution of Dr. Anthony Fauci

Norwood said the uprising, while unsuccessful, did denote larger pacifist anti-war sentiments that the rebels were playing off. While the Socialist Party and Ameringer discouraged the uprising and it was not an official socialist sponsored act, it led to the first wave of the party’s decline.

"It's after 1920 or so it declines very fast,” Norwood said. "The peak is really in the 1910s. Historically, the party itself is just really a shell after 1932."

There was a brief resurgence with the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Democrat who united many of the people who had supported socialism, including small farmers, labor unions and African Americans.

Socialism’s effects on other movements

Like the rest of the country, Oklahoma saw the development of unions with the growth of the socialist movement. Most of Oklahoma's unions found their start with socialist leaders like Ameringer.

The Oklahoma Renters’ Union and Twin-Territorial Federation of Labor, later the Oklahoma Federation of Labor, were among the earliest established in the state. These unions like their national counterparts led pushes to improve working conditions for workers across a number of industries.

Ameringer and many leaders in the socialist movement across the nation were also advocates for African American rights. However, in Oklahoma this is one area where the party largely ignored progress, Norwood said. While Ameringer pushed to overturn Oklahoma’s grandfather clause, an amendment to the state’s constitution that took the right to vote away from most Black residents, many other socialists were not concerned with these matters.

“That's always a problem in that period and for labor organizing generally is that there is a significant amount of racism among poor whites,” Norwood said.

More: Democratic US Senate candidate Madison Horn gets to stay on ballot in Oklahoma

The development of the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union during the Great Depression, an interracial union that originated in Arkansas but quickly spread to include many Oklahoma farmers, would begin a shift in attitudes.

Norwood said racism still existed in the Socialist Party, but the party did “go beyond the two major parties in their proposals on civil rights.” As the civil rights movement advanced, more socialist leaders in the African American community emerged, including Bayerd Rustin, the organizer of the 1963 March on Washington.

“I think the one thing that the socialists probably put out there is all people are human beings deserving to be treated with dignity, to have a fair shake in life, to have some protection against sudden impoverishment.”

Norwood says socialism today is a "watered down" form of the earlier movement, adopted by others parties, including those who would now classify themselves as liberal Democrats or leftists.

“Socialism as it's defined now is also not quite what it used to be,” Norwood said. “The classic definition of socialism is the public ownership of the means of production and distribution. Anyone calling themselves socialists now isn’t going that far; it's more building a safety net.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: How Oklahoma's Socialist party shaped the state

generic

generic