Multiple arrests made after homeless advocates protest outside homes of Columbus officials

The residences of three Columbus city officials became the site of protests Sunday evening as advocates for the homeless held demonstrations attempting to sway leaders to halt the looming eviction of those residing at a homeless camp on the Near East Side.

According to the Columbus Division of Police, four people were arrested and a fifth was issued a summons — all cited for trespassing on private property during the protests at the homes of City Council President Shannon Hardin, Councilwoman Shayla Favor and City Attorney Zach Klein.

First Collective, the nonprofit group of social justice activists that operates what has come to be known as Camp Shameless on Mound Street, livestreamed the protests and arrests of demonstrators on social media.

As protests unfolded, First Collective also shared on Twitter a list of five demands it has for city officials, including the rescinding of the planned eviction of those living at the camp.

The city issued a trespass notice in late July to those residing on the land, which is partially owned by the city, instructing them to leave the camp by Thursday. However, that notice has since been extended to Sept. 14.

Signally their desire to remain at the site, First Collective activists say they've submitted a proposal to the city to convert the land into a tiny home settlement, but that the plan was dismissed by the city.

Ahead of Sunday's demonstrations, First Collective had begun raising money for its legal fund via social media, foreshadowing that its leaders anticipated that arrests would occur.

“We knew that was a risk; it’s always a risk when you’re protesting,” said Elizabeth Blackburn, a First Collective volunteer who lives at the homeless camp. “It just felt as a group that it was important to take the fight to the people who were making decisions and to the people who were most responsible for the situation."

A total of eight individuals demonstrated outside of the three houses, with five of them ultimately being arrested, Blackburn said. One of those arrested uses a wheelchair and for that reason was not able to be booked at the jail, and so was instead given a court summons, Blackburn said.

Three arrests occurred outside of Klein's home, according to Blackburn.

The remaining two activists were arrested Sunday evening outside of Hardin's residence after Hardin called police dispatchers around 5 p.m. to notify them that demonstrators had set up tents, sleeping bags and signs in his front lawn, according to an affidavit of probable cause filed in Franklin County Municipal Court. Court records state that Hardin talked to the demonstrators, who refused to leave when asked.

Among those arrested was Clintonville resident Joe Motil, a local activist who has said he's preparing for a mayoral run. When reached by The Dispatch on Monday morning shortly after being released from jail, Motil confirmed the account contained in court records of his arrest.

"We had everything all ready; we had tents that just pop up real quick," Motil said. "We had sleeping bags, pads to sleep on, we had a cooler for water, we had signs to put up."

In a release shared later on Monday, Motil said he had an interaction with Hardin where he said Hardin told him that he was not interested in engaging with Motil in this way and that he would call the police if they did not leave.

"Hardin refused to have any dialogue with me in his front yard with respect to the scheduled bulldozing of the Camp Shameless," Motil said.

After refusing a police request to move into the public right of way, he and another demonstrator were cited for misdemeanor trespassing and put in a police van bound for the Jackson Pike jail, where Motil said they were fingerprinted, had mug shots taken, and spent the night in a holding area with about 50 men. Motil said the protesters were released Monday morning on their own recognizance without posting bond, and were given a Thursday court date.

Because Klein's home was among the locations where arrests occurred, a spokeswoman for his office confirmed that a special prosecutor will handle the cases to avoid a conflict of interest.

Expressing disappointment with the method protesters chose to express their objections, city leaders reached Monday by The Dispatch insisted that they have maintained continual dialogue with activists and others about strategies to address homelessness.

"We recognize that homelessness is a problem in our city, and as community leaders, we have to continue to work hard to ensure that people are able to receive the help and services they need," according to a statement from Klein's office provided to The Dispatch.

Mike Brown, Hardin's chief of staff, said in an email to The Dispatch that the Columbus City Council has requested and received information from the Department of Development regarding the Mound Street camp, which they understand to be unsafe and unsanitary.

"Council President Hardin offered to meet with folks this week to discuss their concerns, but several chose to stay camped in his yard and were arrested," Brown said. "Our goal as always with the Community Shelter Board and other partners is to assist as many people as possible to choose to get the housing or treatment they need."

A spokesperson for Favor referred comments to Hardin's office, as well as to the city Department of Development.

Among First Collective's demands is also a request that matters in Columbus involving the homeless population be moved from the jurisdiction of the city's Department of Development and to the Columbus Public Health due to the fact that many who are chronically homeless also suffer from mental illness and addiction.

Other demands from First Collective include that the city end the Environmental Remediation Contract associated with encampment sweeps; that the city create a committee to review and revise policies around homelessness; and that the city make space and funding available for overnight warming centers during winter months.

Michael Stevens, the city’s director of development, said his department has collaborated with First Collective on possible solutions, but that these new demands had never been communicated to his office. He declined to comment about their feasibility until his office had more time to review the requests.

“I do find it very unfortunate that they resorted to political theater on the private property of elected leaders who are working to identify solutions,” Stevens said.

Prior to opening the camp at the end of March, First Collective had operated one such warming center at the Old First Presbyterian Church on Bryden Road.

In the months since the camp opened, anywhere from 15 to 20 people have lived at the site, including some organizers with First Collective.

As community donations poured in, the camp grew, amassing a stockpile of food, medicine and other supplies. Volunteers and the camp's homeless residents built fences, hung signs and installed solar panels to provide a stable power source, while outreach workers have regularly visited the site to connect residents with housing services and addiction treatment.

However, when city leaders became aware that volunteers at the camp had begun building a permanent structure that was cemented into the ground, they took action. City officials have also said they became aware of illicit activities and public health concerns they allege are prevalent at the camp, including alleged drug use and littering.

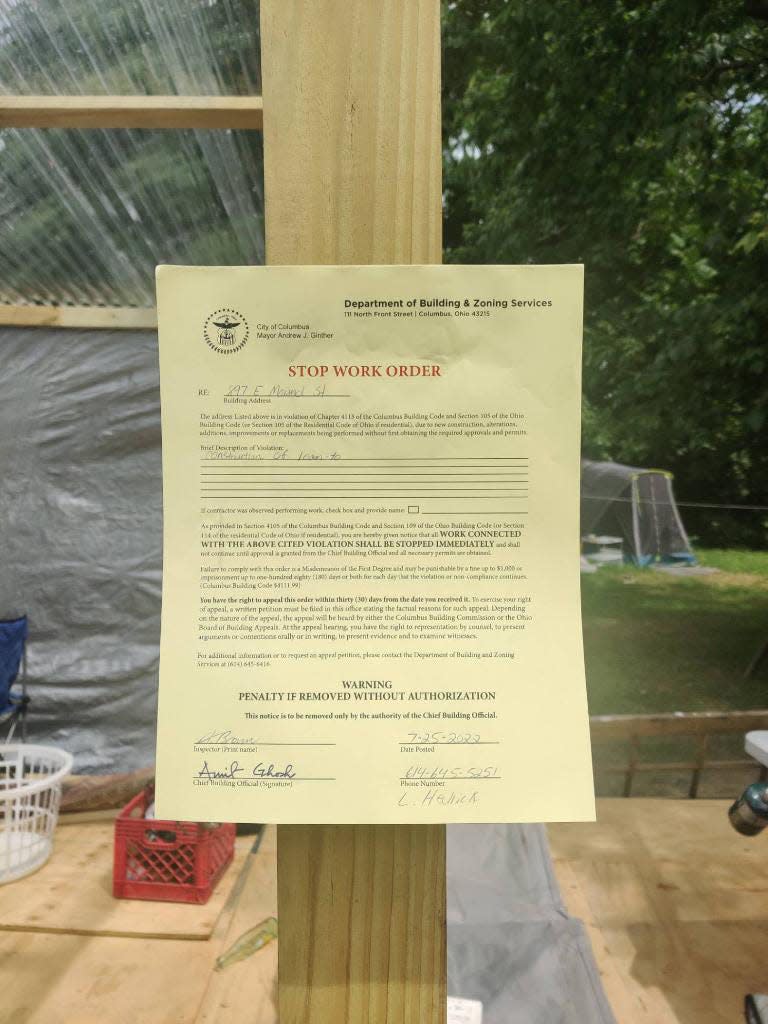

On July 22, the city issued a work stop order in regards to the structure, which volunteers at the camp removed from the ground and adhered to wooden pallets. That order was followed on July 28 with a trespass notice to the camp informing them that they would need to leave by Sept. 1.

Now that the notice has been extended until Sept. 14, city officials hope it will provide more time to help those residents who remain at the camp to be connected with services they need, whether it be housing assistance or substance abuse treatment facilities.

According to the Department of Development, eight of the 12 or 13 individuals staying at the location have completed paperwork to transition into housing. The four remaining individuals staying at the camp have been offered assistance, which they have declined.

“We'll continue to offer them assistance and resources, but we can't condone actions that break the law," Stevens said. “We need to address that and do this remediation, but that doesn't mean we're not going to continue to serve those individuals and make sure we meet their needs."

In the meantime, First Collective is hosting a resource fair from 8 a.m. to noon Thursday at the Mound Street camp.

"It’s our hope that we can continue to work with the outreach people and arrive at a solution for the residents," Blackburn said.

Dispatch reporters Bethany Bruner and Bill Bush contributed to this article.

elagatta@dispatch.com

@EricLagatta

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Homeless advocates arrested at protests at homes of Columbus officials

generic

generic