Georgia bird and poultry experts work to prevent spread of deadly avian flu

Throughout the country, a highly transmissible avian flu has been sweeping through bird populations.

To protect Georgia flocks, poultry experts are working to monitor and prevent the disease to safeguard beloved wildlife and one of Georgia's most productive industries.

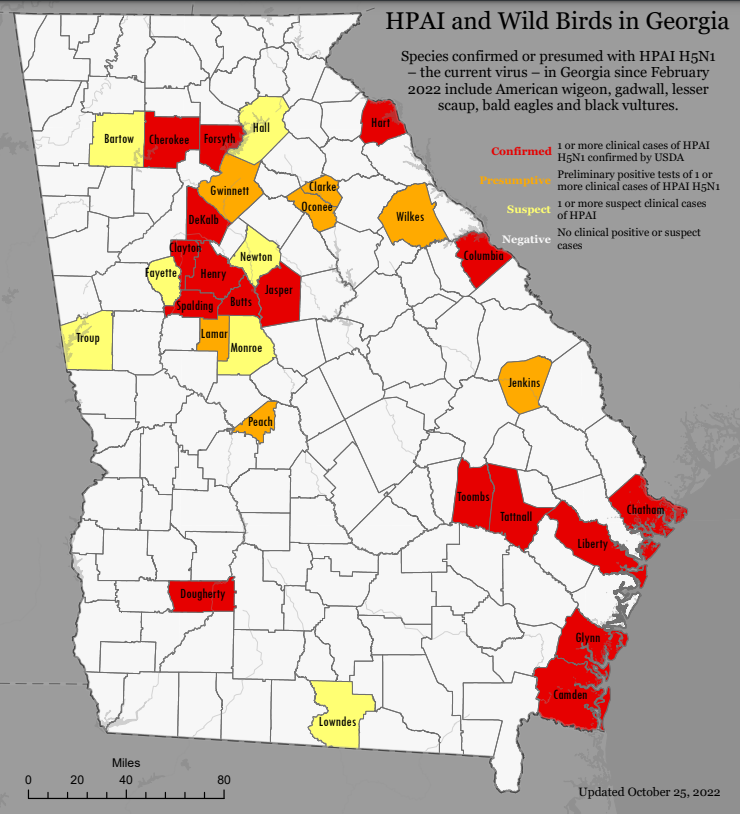

The Georgia Department of Natural Resource's Wildlife Division has detected Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in several counties throughout the state, with more counties containing possible cases.

Swamp mine: Okefenokee Swamp mine is back on as Army Corps of Engineers settles lawsuit

Saving the bees: New vaccine under development at UGA might help save some honeybees

Wild birds, which can travel far distances, are a vector for the virus and its spread across counties. Counties designated yellow and orange on their map have samples headed to state and national labs for multiple levels of confirmation.

While cases of the illness has sprung up throughout the country, there have been limited cases in Georgia's managed flocks. In June and August, HPAI was detected in Toombs and Henry counties, respectively.

What is HPAI?

The current avian flu outbreak is due to H5N1, which is highly pathogenic, meaning the virus is highly infectious and has a greater potential to kill birds. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, this strain of virus hasn't been passed from human-to-human, and overall human infections are very rare. There's only been one reported human case in the U.S., and it was a worker who was in direct contact with deceased birds.

According to Georgia's state veterinarian Dr. Janemarie Hennebelle, waterfowl – like ducks and geese – and other wild birds contribute to the spread of HPAI by shedding the virus into the environment. It can then come into contact with domestic poultry, like backyard chickens.

HPAI doesn't show up as a sniffly-nosed chicken, though. Hennebelle said symptoms for the illness can include a drop in egg production, discolored combs (the rubbery flesh on a chicken's head) and feet, decreased food and/or water consumption and sudden death.

In the wild

Bob Sargent, program manager and wildlife biologist focusing on non-game wildlife for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, said he first encountered HPAI with bald eagle nest surveys last winter.

On Georgia's coast, the virus in March was detected in failing eagle nests, where baby eagles were dying at unusual rates. Before that, hunter-harvested ducks in Hart County tested positive, as well as ducks which washed up on the coast during February and March.

Cases had already occurred in neighboring states like Florida and throughout the country, Sargent said. In Georgia, eagles have been a species of concern, and Sargent said that vultures – which can eat infected carrion and are naturally social, sharing the virus among themselves – are greatly impacted by the virus.

Birds of prey have been the most affected, Sargent said. Songbirds have been far less impacted, although songbirds which eat carrion like blue jays and crows have tested positive.

Managing the flocks

Controlling a virus in wild birds is a major challenge, with Georgia focusing on surveillance and identification. But for the backyard and commercial flocks, there's increased vigilance and protections the state is preparing.

"The key to keeping HPAI out of commercial and backyard flocks is to practice good biosecurity," Hennebelle said.

When HPAI is detected in commercial or backyard flocks, the Georgia Department of Agriculture (GDA) implements its response plan, which includes quarantining and culling the affected flock. The agency also does surveillance of birds near the premises of the ill ones to ensure the virus doesn't spread.

Other recommendations for good biosecurity include:

Separating your flock from exposure to wild birds and contaminated material, equipment, supplies, etc., by creating a line of separation to keep what is outside of your chicken house out.

Using dedicated boots and clothes while entering your chicken house.

Apply disinfectant to boots when entering a chicken house.

Avian influenza doesn't pose a threat to the food supply, Hennebelle said, but it significantly affects poultry health and a quick response is necessary to contain further spread.

Local response, nationwide coordination

Poultry farming is a top industry in Georgia.

According to the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension, broilers and eggs are Georgia's two largest agricultural commodities, making up nearly 40 percent of the state's production value.

Given its importance to the state economy, Casey Ritz, a professor focusing on poultry in UGA's Center for Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, said state and national collaboration is key to protecting flocks.

Limited breeding: Georgia DNR limits ownership and breeding of Burmese pythons, tegus and other reptiles

Endangered: Georgia gopher tortoises skirt endangered status citing steady conservation

Ritz said the UGA Extension has partnered with the Poultry Lab Network, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Georgia Department of Agriculture to respond to the viruses spread, but the UGA Extension is taking a lead in education.

The UGA Extension also has upgraded its webpage with more information and ways to report cases of concern. Through guidelines the office developed, county extension agents have been trained to "triage" and walk through a checklist to determine if a poultry veterinarian is needed to investigate a possible case of HPAI. They are also prepared, with other agencies, to conduct proper disposal of infected birds.

When to report

Not every single bird death is a likely HPAI case, and the DNR has guidance for the public to decide whether or not to report bird mortalities. The public should not approach or handle sick or dead birds to reduce the risk of transmitting disease.

Georgians should report multiple dead vultures, crows, waterfowl (ducks and geese), waterbirds (cormorants, pelicans, herons and egrets) and shorebirds (gulls, terns, sandpipers, plovers) seen at a single site.

The agency also recommends reporting individual dead or sick birds of prey (eagles, hawks, falcons, owls and osprey).

If you find multiple dead songbirds or other species not specified above, call 1-800-366-2661 or a local DNR office.

To learn more about HPAI or to report a group-bird mortality, visit bit.ly/3Xefu5e.

Marisa Mecke is an environmental journalist. She can be reached at mmecke@gannett.com or by phone at (912) 328-4411.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Poultry and bird experts protect against highly infectious avian flu

generic

generic