I Became The Poster Boy For Monkeypox Activism, But There’s Much More To This Story

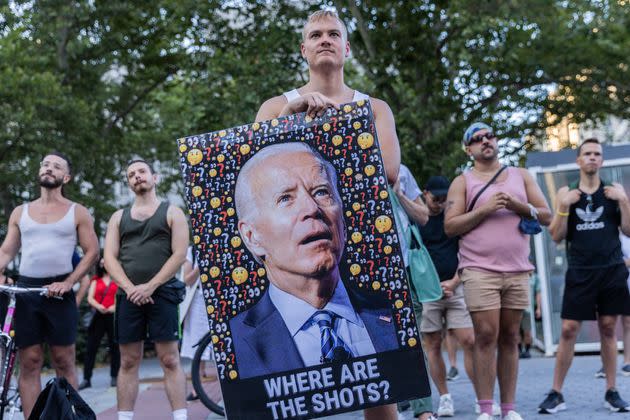

The author (center, in blue shirt) seen at a July 21 demonstration in New York City, calling for government action to combat the spread of monkeypox. (Photo: Jeenah Moon via Getty Images)

Whose suffering is deemed worthy of being considered a crisis, and whose can be dismissed as normal and ignorable? How much pain is required for an emergency to be declared?

These are political questions I’ve been thinking about for years as a historian of catastrophes, and they’ve once again become tragically relevant as another infectious disease spreads around the world. As a scholar who mostly concerns himself with relatively obscure German philosophers, I never expected to be quoted in The New York Times applying their insights to a gay health crisis in 2022.

The Biden administration has declared monkeypox a national health emergency, a step that will allow for quicker allocation of funding and resources for health agencies, vaccination and treatment. It has also added to its emergency task force LGBTQ figures such as Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, a national authority on HIV/AIDS. These are very welcome steps, but they are also long overdue.

Why did the administration wait until there were more than 7,000 cases of the infection ― almost certainly a drastic undercount ― to mobilize resources that, if deployed two months ago when cases were still in the low dozens, might well have nipped the outbreak in the bud? As everyone already seems to agree, monkeypox has been a public health catastrophe playing out before our eyes since the first case was reported in the U.S. on May 18. The opportunities we had for containment in the meantime were squandered, and subsequently we have seen serious inequities in access to vaccination and treatment.

On July 23, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a “global health emergency,” the strongest call to action it can make. A week later, New York City did the same, despite having already been the center of the outbreak for weeks. The WHO finally recognized this emergency only because its director overruled a split emergency committee to insist that the loudest alarm bell should be rung. Previously, the group apparently decided monkeypox did not meet the threshold of an “emergency” partly because it had not spread beyond the primary risk group, men who have sex with men.

That’s right: As long as monkeypox was only spreading at an uncontrolled rate among gay men — many of whom were experiencing extraordinary suffering — it was not seen as an emergency.

At the same time, this virus has been endemic in places like Nigeria for years. Virologist Joseph Osmundson recently lamented that we don’t have any clinical data on either the Jynneos vaccine or the TPOXX antiviral drug: “We have no human data because we ignore the suffering of people in Central and West Africa.”

As with COVID-19, experts now finally seem to agree this outbreak is an “extraordinary event” requiring an urgent global response. I jumped at each declaration of emergency and shared it on social media. At last, the world seemed to have woken up to the nightmare affecting people I care about in the queer communities to which I belong, in New York and Berlin. The evening of the WHO’s declaration, I went out dancing in Brooklyn with friends, unsettled by the outbreak in our midst but feeling more secure than most, and navigating the risks as I went. It’s become a familiar routine: asking people about their status.

My friends and I were some of the lucky few who received a first dose of the highly effective vaccine several weeks before. (An article at Science notes that the second dose mainly extends rather than enhances protection, and many agencies have rightly prioritized distributing first doses.) At that point, New York City had distributed just a few thousand doses, woefully inadequate given its estimated 700,000 queer residents.

The WHO apparently decided monkeypox did not meet the threshold of an 'emergency' partly because it had not spread beyond the primary risk group -- men who have sex with men.

Imagine my surprise when I awoke Monday after the WHO’s declaration to find my phone bombarded with notifications. I had become a poster boy of activism demanding stronger government response to the outbreak, with my face and protest sign accompanying coverage on Al Jazeera and “NBC Nightly News” with Lester Holt, and in print and online articles about the outbreak from Le Monde, NPR, the BBC, Gay City News, Forbes India, Them, The Washington Post and, most recently, on the homepage of Vox. Friends kept sending screenshots and messaging me, “You’re famous!” I responded, “I’m just one angry fag.”

A few days prior, I had attended a rally for action on monkeypox co-organized by a number of progressive queer activist organizations, including ACT UP New York and PrEP4All, for which I have enormous respect. The crowd that evening, consisting mostly of gay men, gathered in the oppressive heat, wearing “SILENCE = DEATH” T-shirts and carrying signs bearing sharp words. One sign read: “You Did This to Us in the ’80s When AIDS Patients Needed Emergency Treatment.” Another declared: “This outbreak didn’t need to happen. We are getting sick because of government failure.”

Hurrying to meet friends at the demonstration, I jotted a slogan in marker on the lid of an empty shoe box: “MONKEYPOX: WHERE IS YOUR RAGE?” Echoing past ACT UP protests going back to its founding in 1987, the demonstration was symbolic and theatrical, but not only that ― it targeted a specific political site, Foley Square, a hub for New York City government where decisions about life and death are made. The site was also chosen because it was close enough that PrEP4All co-founder James Krellenstein could lead us in chants of “SHAME! SHAME! SHAME!” directed at the adjacent offices of the city’s under-resourced and, at the time, unresponsive Department of Health.

I found it ironic, and frustrating, that the photo of me and my white cis-male gay friends had taken off, when the demonstration had been admirably organized to platform the voices that are so often marginalized when it comes to public health issues. Speakers included veteran activists, queer people of color, trans men and women, sex workers and those living with disabilities and HIV, as well as a few local politicians.

The organizers made a series of demands to expand vaccination and treatment, some of which, like releasing the antiviral treatment TPOXX from useless bureaucracy, have since been partly accomplished. Others, like getting the Food and Drug Administration to approve the hundreds of thousands of ready vaccine doses we have left sitting unapproved in a plant in Denmark, remain a national embarrassment and outrage. Further demands like providing financial support for those who are infected and cannot work, or who need alternate housing to quarantine, have yet to be addressed.

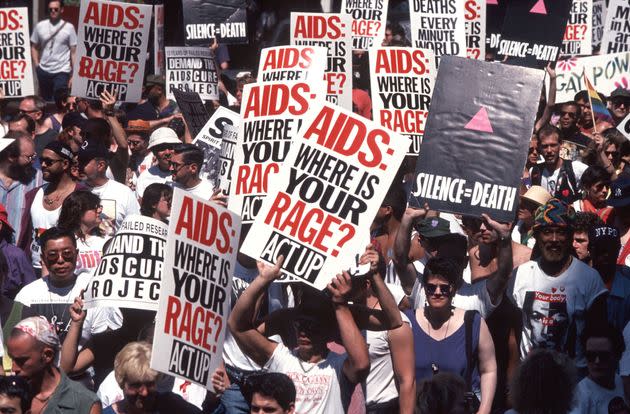

I was glad my protest sign struck a chord, because it conveys a long history of queer activism channeling anger. I was specifically inspired by an ACT UP New York banner and poster I recalled from the New York Pride March in 1994, which celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. The poster read: “AIDS: WHERE IS YOUR RAGE?” The reverse of the poster reads “HOW MANY OF US WILL BE ALIVE FOR STONEWALL 35?” The context had changed, but there we were again ― a bunch of queers pissed off and united in our anger.

An ACT UP demonstration at the 25th annual Gay Pride Parade in New York City on June 26, 1994. Many demonstrators carried a sign reading "AIDS: Where is your rage?" -- which would inspire the author's monkeypox sign in 2022. (Photo: Allan Tannenbaum via Getty Images)

In 1994, livesaving combination therapy drugs were still two years away, and people with AIDS were dying in droves, with AIDS deaths in the U.S. that year topping 40,000. Even AIDS activism had lost steam, as ACT UP splintered and many who had joined because they had nothing left to lose succumbed to the disease themselves. 1994 was a low point, when the light about to emerge at the end of the tunnel could not yet be glimpsed. When lifesaving treatments finally came out in 1996, some, like the conservative gay writer Andrew Sullivan, myopically proclaimed “the end of AIDS,” thinking only of white, privileged gay men with access to these still extremely expensive drugs.

That victory, we can now see plainly, was short-lived. Twenty-five years later, hundreds of thousands of people around the world were still dying from AIDS each year, including in our own backyard. A Gregg Bordowitz exhibition last year at MoMA PS1 in Queens provocatively proclaimed on huge banners: “THE AIDS CRISIS IS STILL BEGINNING.”

Last year I published an article titled “When does an epidemic become a ‘crisis’?” on analogies and disanalogies between the AIDS crisis and COVID-19. Following the onset of the pandemic in 2020, I was struck by insights about pandemics generally for the COVID crisis du jour from veteran AIDS activists like Larry Kramer, Sarah Schulman and Cleve Jones, as well as writers like Susan Sontag who had addressed the epidemic through fiction. There were certain obvious parallels between the two, such as New York being an epicenter, with corpses piling up in hospital hallways and an early mood of uncertainty and fear. But what interested me more were the disanalogies. One epidemic potentially affected everyone, whereas the other, at first, seemed contained to marginal groups.

Early on in the COVID pandemic, AIDS activist Mark King thus bristled at the analogy, calling it “offensive.” “In the early 1980s, AIDS was killing all the right people. Homosexuals and drug addicts and Black men and women,” he wrote. “There is no comparison to a new viral outbreak that might kill people society actually values, like your grandmother and her friends in the nursing home.” While COVID-19 was quickly declared a global crisis demanding unprecedented response, AIDS languished for years as a non-crisis — ignored or even justified suffering — and only became a crisis over the course of years, after it was made into a political issue by groups like ACT UP.

By reactivating a slogan from the AIDS crisis, I hoped to channel the political emotions that made ACT UP, according to Schulman’s recent history of the group, one of the most effective social movements in recent history, saving countless lives. According to its mission statement, ACT UP brought together diverse coalitions “united in anger” and dedicated to ending the AIDS crisis. Its roots can be traced to a 1987 speech that Kramer gave at a New York LGBT center, where he began by asking two-thirds of the audience to stand up, and told them that they would be dead in five years if they didn’t act. “If my speech tonight doesn’t scare the shit out of you, you are in real trouble,” he said. “If what you’re hearing doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage and action, gay men will have no future here on Earth. How long does it take before you get angry and fight back?”

Galvanized by the talk, many decided to meet weekly to stay informed on the HIV/AIDS struggle. Activist David Barr later reflected: “Rallying together and expressing our anger was a really good replacement for just feeling scared all the time ... The anger is what helped us fight off a sense of hopelessness.”

At first glance, the comparison between anger about the two months of bungled government response to monkeypox and years of criminal inaction on AIDS can seem inappropriate ― or, as King said of the COVID analogies, even offensive. Thus far, there have been no deaths related to this outbreak, though that could change if the disease spreads to elderly or immunocompromised populations. But some analogies are impossible to overlook. As New York state Sen. Brad Hoylman (D) recently said: “Because it’s impacting such a limited population — I hate to say, meaning gay and bisexual men — the sense of urgency is lacking.” And as Andy Garcia and Jesse Milan Jr. said about the ’80s in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: “Vulnerable communities recognized early on that the government was not going to help us. They didn’t act because ‘the right people were dying.’”

People, including activist Wyatt Harms (center), protest during a July 21 rally at New York's Foley Square calling for more government action to combat the spread of monkeypox. (Photo: Jeenah Moon via Getty Images)

These diseases differ greatly, but the response to monkeypox should nevertheless be guided by warnings to avoid the failures of the AIDS crisis, as several articles offering “lessons from [the] AIDS crisis” have advised. Watching the case count climb, it has seemed scandalous to those who lived through the AIDS crisis how little has been learned about pandemic response and the value of public health for moments of exigency.

Beyond the group affected by the disease, there lie deeper, structural analogies. “The stark and clear parallels are the lack of investment and the negligence,” said Jason Rosenberg of ACT UP New York. “We saw little to no investment when we saw the few outbreaks that were happening in May. AIDS activists told the federal government back in May that we need to act on this, we need quicker investment in our stockpile of monkeypox vaccines. And time and time again, they refused that call to action.”

What’s so frustrating to those who have been watching this outbreak grow the past two months is that it was largely preventable. Unlike HIV or COVID, monkeypox is a known pathogen for which we already had millions of doses of highly effective vaccines. This is an outbreak that we had the resources to contain. It’s just that several levels of government failed to do so.

But there was another, more palpable reason for my anger at the rally: Some of my friends have endured indescribable pain, yet for weeks, few were willing to talk about it or able to be heard, given false assumptions in the medical community about the effects this “mild” virus had. Patients now liken their experience to shitting glass, having a hot curling iron up your ass, crying every time you have to pee, and being in so much pain that you can’t sleep for days without narcotics. Finally, the same day the WHO proclaimed monkeypox an emergency, The Guardian ran a story with the headline “‘I literally screamed out loud in pain’: my two weeks of monkeypox hell.”

Of course, this is not the same as mass death. Still, we should recognize it as terrible suffering that’s all the more tragic because much of it could have been prevented. These people’s pain, unacknowledged and even denied, caused my rage.

Why are we not talking about the painful reality of this disease? Because it’s embarrassing or uncouth? Because it’s disgusting and may further stigmatize the affected, predominantly queer communities?

“There is a shame involved in this,” said the activist Mordechai Levovitz. “There is a taboo. This is something that, for people who had [rashes and lesions] on their face, something that they can’t hide.”

King noted that for older men, the lesions can trigger memories of compulsively checking one’s body multiple times a day for Kaposi’s sarcoma, the characteristic lesions associated with AIDS ― thus bringing back the trauma of “the revolt of our own bodies, our fear of being disfigured, the unease that it might actually be punishment for our wicked ways.” Monkeypox has so far not proven deadly, but my community is again being traumatized and scarred. And we still don’t know enough about other possible effects like blindness.

Monkeypox appeared on my radar in mid-May. A partner of mine in Berlin attended the Darklands sex festival in Belgium, where some of the first cases were reported. In those early days, media puzzled about whether and how to report on a disease spreading mostly among men who have sex with men. By May 22, a United Nations agency denounced some rhetoric surrounding the illness as “homophobic and racist,” noting that stigma and shame interfere with education and treatment. A few days later, Slate warned that monkeypox could generate a wave of homophobia, and urged against linking it with gay sex until more evidence emerged. But now we have that evidence: Thus far, 95% of cases have been linked to sex, and 98% of infected people are gay or bisexual men or men who sleep with men.

It is only our anger that will protect us.Mordechai Levovitz, activist

Still, the history of AIDS shows that it is crucial to avoid labeling monkeypox a “gay disease” or even a sexually transmitted one. AIDS was initially called “gay-related immune deficiency,” which led to stigma regarding not just AIDS but also groups like women, babies, and hemophiliacs being denied access to testing, drug trials and treatment. With children recently contracting monkeypox, there’s reason to think this disease, too, could very well spread. Days before, at the rally, Levovitz had reflected on how this might fuel conspiracies about LGBTQ grooming. “In a few months from now, on the front of every magazine will be children with monkeypox on their face. And they’ll blame us for this,” he said. “It is only our anger that will protect us.”

Despite the lessons of AIDS and COVID, the official response to monkeypox has been a disaster at every level of government. Starting in June, I heard horror stories of people exposed to the virus who could not get a vaccine or drugs that could have drastically ameliorated their sickness. I heard about other people, in agony, being turned away from emergency rooms and sent from doctor to doctor. ACT UP veteran Peter Staley was included on a large call with the Biden administration in early June, leading him to prematurely thank the administration for its early response in contrast to the AIDS crisis. But Staley has since condemned the U.S. response, calling it a “fucking mess,” and said, “There’s just nobody acting like this is a fucking emergency.” While he said this response was not “AIDS 2.0” ― recalling how the Reagan government ignored gay victims due to blatant homophobia ― Staley described it as “COVID 2.0,” a repeat of the very same mistakes.

Vaccines have been haphazardly and unequally allocated through crashed websites, long lines and unanswered calls to health agencies. Friends have likened getting a vaccination appointment to the Hunger Games. The latest round of thousands of additional vaccine appointments filled up within minutes. Many areas of the country have received no vaccine allocations at all. Scalable commercial testing was slow to be approved, and there is still no guarantee that it will be free as COVID tests are; we simply have not allocated enough resources.

The response thus far has been chaotic and inadequate, “like saying we have a tanker of water coming next week when the fire is happening today,” says Gregg Gonsalves, an ACT UP veteran and Yale epidemiologist. Meanwhile, my queer friends in Canada were fully vaccinated many weeks ago, thanks to a rollout that has even attracted vaccine tourists. That proactive and coordinated response is much closer to what public health should look like.

Public health in America doesn’t have to be in such shambles. Indeed, it wasn’t always this way. At the rally, ACT UP veteran and Treatment Action Group founder Mark Harrington reminded the mostly younger generation present about the remarkable response to the 1947 smallpox outbreak in New York City. Within just three weeks of its discovery, the U.S. Public Health Service and city health officials procured enough smallpox vaccine, largely within the city in public vaccine manufactures, to inoculate more than 6 million people. What could have been a deadly outbreak was nipped in the bud and resulted in only 12 infections and two deaths.

Much of that infrastructure and know-how has been lost through decades of underinvestment and privatization since the Reagan years. It seems it is only in times of crisis that the American public remembers that health care is and has always been a right. Harrington’s remarks reflected key lessons from ACT UP: Political progress is not won by heroic individuals, but by broad coalitions, and government only responds to crisis when it is forced to do so. Staley already says he regrets trusting the Biden administration’s early promises about the steps it was taking. “We dropped the ball,” he said. “We just should have stayed in screaming mode every step of the way.”

“Who keeps us safe?” we chanted at the rally. And we answered ourselves: “We keep us safe.”

“Who protects us?”

“We protect us.”

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. candidate in history and humanities at Princeton, where he is writing a dissertation about the concept of catastrophe in 20th-century German thought.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.

generic

generic