‘Genius’ Helmer Michael Grandage On Filming ‘Guys And Dolls’ And The Kinship Between Lit Editors And Stage Directors

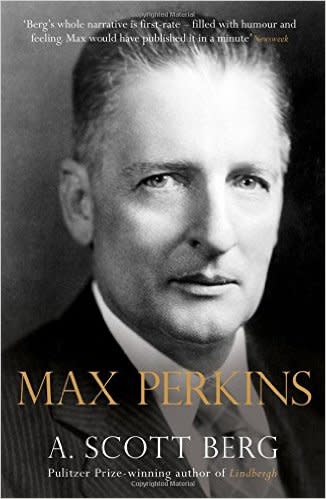

While the focus of most in the New York stage community last week fell on the Tony Awards, Tony-winning director Michael Grandage spent his Gotham week promoting Genius and mobilizing his upcoming bigscreen version of the classic musical Guys and Dolls, which he’ll direct for Fox. Genius is a small gem of a film that stars Colin Firth as famed Scribner’s literary editor Maxwell Perkins. He develops an unusual father-son relationship with bombastic novelist Thomas Wolfe, adding him to a stable of writers that included Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Jude Law plays Wolfe and Nicole Kidman and Laura Linney also star in an adaptation of the A. Scott Berg biography scripted by John Logan, with whom Grandage collaborated on the celebrated stage play Red. Grandage, who took over as artistic director of the Donmar Warehouse after Sam Mendes left to direct films, has directed stage plays at a prolific pace and waited until age 53 to make his way behind the camera. Sounds like he’s here to stay as he focuses on Guys and Dolls and a movie version of Photograph 51 with Kidman.

DEADLINE: In Genius, you and John Logan have made a movie about a literary editor who spent his days red penciling prose to bring out the best in Thomas Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. This is your first film after years directing stage productions, bringing out the best from major stars. Is it too much to imagine you identified most closely with the literary editor Maxwell Perkins on those grounds?

GRANDAGE: Well, you’re correct and interestingly enough you’re the first person I’ve talked to who’s said it before I’ve said it. Most people just say why did you want to direct this movie, and don’t really see the clarity of the link between the editor and the role of the director. Nobody really knows what a director does, certainly in the theatre I can speak for that. I like that. I think it’s this great privilege of working with a role and extraordinary talent, honing it and working with to bring it before the public. And when we’ve done it, we take a back seat to let them have the relationship with the audience. So there is certainly a parallel there. When I read the script, the appeal was this overriding friendship between Perkins and Wolfe that exists on the page and you know would be dramatically good because most films are based on a central friendship or a central relationship of some kind.

DEADLINE: How hard is it though, to make the red penciling of words cinematic?

GRANDAGE: How do you make the editing process, and literature, dramatic? That came down to the nature of their relationship with the words. But certainly the way in for me when I first read this screenplay, was that it felt like someone opened a little secret door of the world of the director and the world of the editor. We do inhabit the same place and that spoke to me on a very personal level. But making Genius for that reason alone wouldn’t have been fruitful. You’ve got to make something come alive in the process of editing a book which has nothing to do at one level with directing a play.

DEADLINE: Beyond opening up a new career in film, what was your objective with this period piece?

GRANDAGE: I’d love it to have a number of things to come out of it. The first thing I’d obviously like is that Wolfe is put back into a place in American literature history that he once had. I believe he was taken off the curriculum in the 1970s, and since then has lost the reputation he once had. A generation since doesn’t even really know who he is. There is certainly a group of people in their late-50s or mid-50s and over who absolutely engaged with Wolfe as young people. They know all of Wolfe’s writings; it was part of their education. Since it came off the curriculum, Wolfe has disappeared. I wish I knew why.

DEADLINE: It is remarkable to watch the scene where a declining F. Scott Fitzgerald talks about how he made two dollars in royalties from The Great Gatsby in the same year that Wolfe made a fortune from Look Homeward Angel. Gatsby is now one of the most revered American novels. Why has Fitzgerald withstood the test of time and not Wolfe?

GRANDAGE: I guess the most obvious thing to say is that we have progressed our way with language to where we now, in the 21st Century, need to speak and say what we need to say in very, very short silent bursts and short sound bites. Where would that leave the big sprawling literary titan who as the film indicates, needed several sentences to say what could be said in one sentence? That was part of his DNA and what he enjoyed doing. Even if this film made some people read Wolfe, would they be able to appreciate him? He refers to it a bit in the film, that he has this Proust-ian tendency to enjoy going off to places, and the reader has to stay engaged and has to want to go off on one with him. I don’t know whether there is a hunger for that anymore where we are now in 2016. I’d like to think there is, and I certainly know there’s a hunger for it in every inquiring mind who is interested in literature. But in the bigger population could Wolfe’s books hold up, whereas somewhere the narrative tension of Hemingway and the narrative tension of Fitzgerald still holds true, their great stories? They say quite a lot, succinctly. It is fascinating that in his day, Wolfe was more successful than both of them, financially, and with the amount of books that were bought when they came out. Somewhere, clearly in the 1970s, somebody somewhere thought fit to keep Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and all the rest of them at the top of the education pile, but then to remove Wolfe. How that came about is probably an investigation in itself.

Putting Wolfe aside, I liked that the film looks at the process of editing. When I travel, when I am on the subway or in a park, I see people reading novels. They engage in the narrative and maybe that’s all that matters, but I love the idea that a film like this in some way helps people understand that behind the book, it wasn’t just a lonely writer in a room writing, and then the book appeared in their hands, but that that is actually a part of that process that includes engagement with somebody else on a very literary level. I have some novelist friends in England and one of them, Edna O’Brien, she was the first person who brought Max Perkins to my attention. She said, ‘The problem these days is a lack of great, great editors. We don’t have a Max Perkins around.” I can’t speak for all novelists, but the ones I know crave great editors. That is part of this, but the core is the emotional central relationship that John Logan rightly focused on in order to make that film dramatically interesting. These sidebars, the notion of editing, Wolfe’s place in the world, the parallels for me between director and editor, I just found it all fascinating.

DEADLINE: Perkins’ working relationship with Wolfe was not unlike capping an oil well, and the trick was to manipulate the writer and make it seem like the editors’ ideas were the writer’s ideas. Though they had a father-son relationship, Wolfe became bitter about Perkins getting too much credit for his success. How do you handle it when you need for actors to carry out your vision, but you want them to think something good was their idea all along?

GRANDAGE: I think it is important always that the director has a vision not just for the actors, but for creative things that range from design to story. You’ve got to be able to answer the question, why do you want to do this play, or this movie, and you’ve got to become good at articulating the big “why” because that is why a lot of people are going to sign up for it. Then it becomes this collaboration, and one of my jobs is to allow that to flourish and not cap the creativity. You need to have everyone support your vision, but you must be open to the possibility that you will have to consider things that might take your vision in a different direction. My process is to always be open to everybody else in the process, and allow things that are occasionally different to your vision, and to not be so closed that you can’t accommodate it. Going into a rehearsal with an actor, you need to have done so much background and research that you know everything that there is possibly to know about the piece. Then you can offer guidance to an actor.

There are three opportunities; it can go one of three ways. First of all, let’s just take the actor. The actor can give the line, it can be lost and doesn’t know how to do a line. Then the next version is that the actor can do a line pretty much as you hoped it would be. Then the third one is that the actor could do something completely different with the line, but is just as valid as anything you had in your head.

DEADLINE: What happens in those latter cases?

GRANDAGE: I think for options two and three the best directors should shut up and keep quiet. I think obviously in option one, I think your job is to come in like an expert, you can help, it may be a fit, but in two and three the actor has found a way how to do the line without you actually intervening so they will have much greater opportunity to own the line. I can sometimes see though performances, where something has been given to a good actor and deep down they know they’re doing it for somebody rather than owning it for themselves.

DEADLINE: How do you avoid that?

GRANDAGE: It’s a very, very fine line and even very, very difficult to notice. But I think I’ve learned that with great actors, if they’re just suddenly there in front of you and say a line, you as the director have to do an immediate assessment in your head. Was that line as good as anything I thought of? If it was, then shut up. I think directors can interfere and affect performances in a detrimental way, but I think one of the most important things about directing is actually letting something happen without feeling your need to show them you’re a director.

DEADLINE: Stage plays evolve not only in rehearsal, but through nightly repetition during the actual run. Features films are different. What was the biggest difference in your first film?

GRANDAGE: The fundamental difference is the great arc of the play that develops when you’re watching it with an audience, whereas in films you work in much, much, much shorter bursts during the shooting period. Sixty seconds to two or three minutes is about a long as it gets for a take. You’re looking at the arc of how it worked within that take, but as director you have to be concerned with the editing process before the editing process has begun, thinking a little bit about the arc of the film and how that take sits. Your process of dissection is different. You dissect in the theatre, in the rehearsal room where you put it all together, and then again when you take it onto the stage, before an audience, and you don’t have to pull it apart in any way. Whereas in film you are looking at an individual scene on the shoot, and you are absolutely analyzing every version of that moment you want or think you might need.

DEADLINE: How do you compensate for lack of experience behind the camera?

GRANDAGE: I was out of my comfort zone for my first feature here, I’d never done it before so I was very aware that I needed a lot of prep. I visited other sets. I visited other editing rooms. I had gotten used to what every part of the process would be, but then you’ll run into all your own film and you can only deal with that. I learned a lot for instance from Nicole Kidman when I was working with her. She is a very seasoned film actress who knew her way around a camera very, very well. We did two or three takes and she knew what I was after. We’d have a long discussion about that before rehearsal and she came phenomenally prepared. We did a couple of takes and by the third take quite frequently I’d gotten what I needed. She was happy that she had delivered it to a certain level, but frequently she would say, “I love this moment with Colin Firth; would you like me to do something completely different now just so you’ve got options in the edit? I discovered that’s the big difference between a film and a play. When you go into the edit you make a different film to the one you shot, and certainly a different film to the screenplay you went into the shoot with. So the film almost gets made three times; in preparation, in the shoot and then in the edit. And the edit is the one you’re left with.

DEADLINE: Michael Fassbender was originally going to play the Wolfe role that went to Jude Law. What’s the hardest thing about taking a not overtly commercial premise and then vamp for backing and find it comes down to foreign sales formulas based on the value of specific actors?

GRANDAGE: The experience was astonishing on many levels. I didn’t appreciate how much finance is raised at one’s given profile at a moment. Not a given profile necessarily earned over time, but how someone has been performing in very, very recent history. So it’s quite interesting that you think that just going back for a nanosecond in the theatre…you build a career in the theatre on the whole. Unless you get off the rails that means you put layer upon layer upon layer in your profile if your life continues to rise as an actor. In film that’s not untrue, but you are definitely only as good as your last film. When I took on this project it had Michael Fassbender and Colin Firth attached, and we went out and started to raise money against those two. Then Michael became unavailable for the period we wanted to do the movie in, and we moved it a little bit and then he became even more unavailable. We decided to part company there very amicably and I was left with just Colin Firth and in the process of raising money. It was at that point that it became about a group of things rather than a single actor.

So replacing Colin Firth and Michael Fassbender with Colin Firth, Nicole Kidman, Laura Linney, Jude Law, with cameos from Guy Pearce and Dominic West, what does that all add up to in the financing of this movie? The answer from all of the people, film management and everybody who had parts of our backing was it fit in very nicely, on the back of this John Logan screenplay that had been doing the rounds for some time. People really admired and respected the script. I found that process completely fascinating.

DEADLINE: How does losing a star like Fassbender impact your creative plans?

GRANDAGE: The other thing that was looking nice to me actually which was while Michael Fassbender was moving out of the film was…the day I remember it happening, it was also a day where I had an opportunity, having inherited those two actors, to stamp my own identity a bit more onto the film by casting somebody I believed could do Thomas Wolfe in the way that I saw Thomas Wolfe in my head. That’s why I turned to Jude at that point. He’s somebody I’ve worked with a lot on stage, and he’s somebody I know as an actor to be the one quality I knew I was looking for, for somebody playing Wolfe. I wanted a theatre actor, somebody to dare themselves to be as big and as larger than life if it’s possible to be and not to do too much self-censoring that they go. In an early scene with Max, he says, ‘I’m not a circus animal you know, I want people to take me seriously.’ But the truth is he comes across as a bit of a circus animal and that’s why he’s so paranoid about it, and I wanted an actor who could embrace that, and I knew the great joy of working with somebody so much whether it’s Hamlet or Henry V or any of those big huge, huge guys. I knew Jude would be that person.

DEADLINE: John Logan spent about 14 years in this adaptation of Scott Berg’s book on Perkins. Between Hemingway and Fitzgerald, those were two authors far more familiar in today’s world, and very eccentric characters. Why Wolfe?

GRANDAGE: It’s a personal story attached to Wolfe that attracted Logan because you’re absolutely right. In his book, Scott Berg deals with Max Perkins’ brilliance across all of his authors. I think the bit that appeals to Logan was less about where he sat in who’s the greatest writer here, and much more that Wolfe became a son that Max never had and wanted. It became a kind of father/son relationship which was one of the great themes that John does explore in his work as he did with his play Red. He was also fascinated by the fact that Wolfe’s life was cut short, so it begs so many questions about what would have happened if he had gone on to live another 30 years in terms of where his place would be in literature now. And there’s so many good dramatic things that Wolfe and Perkins bring up that maybe a film about Hemingway and Perkins or Fitzgerald and Perkins wouldn’t necessarily offer, in the dramatic part of their lives together rather than the literature. It’s something that governed John’s keen interest in it.

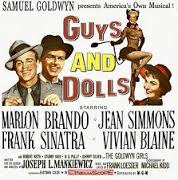

DEADLINE: So you’ve gotten a small movie under your belt and now you’ll direct Guys and Dolls, about the highest profile musical project one could imagine. Hollywood has tried to mount this for almost two decades, with every actor who can sing vying for the roles played in the movie by Sinatra and Brando. You directed a West End revival of the show, so what can you tell us about how you’ll make a period piece relevant, and are big actors now banging down your door?

GRANDAGE: Since your piece came out actually, the floodgates have opened. So thank you, actually. I had such an extraordinary time during Genius and I didn’t know I was going to. Remember, I’d put off film because I decided you shouldn’t really leave theatre to make a film, if you are running a theatre company. That’s what I did, and I put off a lot of very interesting scripts that had come my way. It just didn’t feel like the right time. Then when this did happen, I seized it and enjoyed throwing myself out of my comfort zone because actually I felt very alive. The whole process of Genius from start to finish was creatively very, very fulfilling, possibly the most fulfilling time I’ve had in my career. Partly because every part of it was new, which is always wonderful. I kept waiting for the day that I wouldn’t enjoy it. Would it be the edit? Would it be the mix? Every single part of it was wonderful. When I sat with my agent Brian Siberell at CAA at the end of that process, he said, ‘Well? Do you want to do another one?’ I said, ‘Hell yes. I’d love to do another one.’ I asked him the status of Guys and Dolls and he came back and said, it’s still with Fox, but dormant. It had a screenplay by Danny Strong and was waiting a director. I went and pitched for it.

I was very clear why I would like to make a Guys and Dolls for a new audience in a new century, but honoring all of the great things that make it Guys and Dolls. I could see it. I wanted to free it completely from the stage which frankly is where even the original film slightly belongs because of the way they designed it, and the way it was very much a piece that captured that first production in the 50s. I want to return it to the 30s where it sat with the Runyon books, but somehow absolutely link it to a modern audience, some of that through the casting, and the way you might perceive certain characters in a different way. I made my pitch and it went very well obviously and Fox bought it. The picked up the rights again and we’re now moving forward with it. And you’re right, I do know the material very well, but I also want to free myself from anything at staging and make a film of it and not make the version of a stage musical of it. The casting will help define that. I’ve come up with a vision that I’m starting now to share with more people because up until last week the only people I was sharing it with was Fox. We’ve brought in a casting director. I’m meeting production designers, costume designers, I’m meeting DPs. I’ve had some meetings in New York, while here promoting Genius.

DEADLINE: You have also said you want to direct a film based on Photograph 51, where Nicole Kidman played Rosalind Franklin, whose role in the discovery of DNA was marginalized. I just wrote about a rival project landing at eOne, which bought the spec script. So now you’ll become part of that movie tradition of a footrace to mount a movie first?

GRANDAGE: I think the film prospects for Photograph 51 are strong in that Nicole Kidman wants to make a movie of it with me. We’ve already got a screenplay from Anna Ziegler, who wrote the stage play, so that’s moving ahead. It’s really about when we do it and how we do it, and I guess in terms of it sitting alongside other versions of the Rosalind Franklin story, it might be one of those things where whoever gets there first just does it. I remember the two Capote films that fell in close proximity to each other, and further back, the two versions of Les Liaison Dangereuses. I’m not sure I’d want to be part of a group of films coming out about Rosalind Franklin. I think one of the joys of Photograph 51, like John Logan’s Red, is that it takes a moment in somebody’s life, and it’s not a biography. A significant moment in their life can tell you everything you need to know about that life, through the prism of that one key moment. We’re on schedule in terms of where we need to be. There’s a very good screenplay. There’s an actress signed up for it, effectively. There’s a director that wants to direct. So it’s really just a question of where it fits in with me doing Guys and Dolls and Nicole doing her next three projects back-to-back. Yeah, I’d like to make that happen. I’d like to make that a reality because my understanding in talking to some other people who have found other Rosalind Franklin material, nobody else is quite that far ahead yet. We’re going to try and get Photograph 51 back onto Broadway at some point, and my company back in England is certainly actively looking for theatre projects to do. Right now we’re putting something together for the end of this year and I may well be involved in one of those in terms of directing. But my next film I think is almost certainly going to be Guys and Dolls. Although one thing I’m learning is that film is not like theatre. There, when we say we will begin rehearsals on September 13, and it will all be over by January 25, that’s usually the way it happens. Not always the case with film.

Related stories

Number 9 Films And StudioCanal-Owned RED Teaming Up for Henry James Adaptation 'Portrait Of A Lady'

Nicole Kidman Joins 'Top Of The Lake' Season 2 In Reteam With Jane Campion

Docs 'De Palma' and 'The Music Of Strangers' Top Weekend: Specialty Box Office

Get more from Deadline.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter