What Israel Could Teach the U.S. about Cybersecurity

A promotion for the Israel Defense Forces at the CyberTech 2016 conference. (Images by Rob Pegoraro/Yahoo Tech)

The first day of the recent CyberTech 2016 conference on cybersecurity in Tel Aviv, Yuval Steinitz, Israel’s minister of national infrastructure, energy and water resources, dramatically demonstrated the urgency of the matter at hand: He admitted that the state electric authority itself was currently “facing a very serious cyber attack.”

His government agency had identified the malware and isolated the infected computers. And the attack affected only a regulator of the electric industry, not the actual power generation or transmission systems. But Steinitz’s point still stood: “This is a fresh example of the sensitivity of infrastructure to such attacks.“

Or, as Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu put it during an address earlier that day: “In the Internet of everything, everything can be penetrated. Everything can be sabotaged, everything can be subverted.”

Israel knows this better than most countries. It has been on the receiving end of numerous online attacks of varying levels of competence (though not as many as the United States receives), and it has launched some particularly advanced and effective assaults of its own — most famously, the Stuxnet malware that it and the U.S. reportedly collaborated on to disable Iranian nuclear centrifuges.

“Israel is one of the top targets of cyber attacks, and also a source of a lot of defensive and offensive cybersecurity technology,” according to Johannes Ullrich, dean of research at the SANS Technology Institute, a cybersecurity research and training organization in Bethesda, Maryland. A report released before the conference by the IVC Research Center, a Tel Aviv tech-startup hub, touted Israel as second in the world to only the U.S. in cybersecurity.

I spent a week in Israel to get an overdue introduction to its cybersecurity sector, courtesy of a trip for a group of U.S. journalists and analysts sponsored by the America-Israel Friendship League, a New York- and Tel Aviv-based nonprofit, and by Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I wanted to see how the countries private and public sectors were coping with cybersecurity threats and to see what U.S. might learn from them.

My conclusion: If only the Israeli approach were something we could pack in a box and put on a plane to the States.

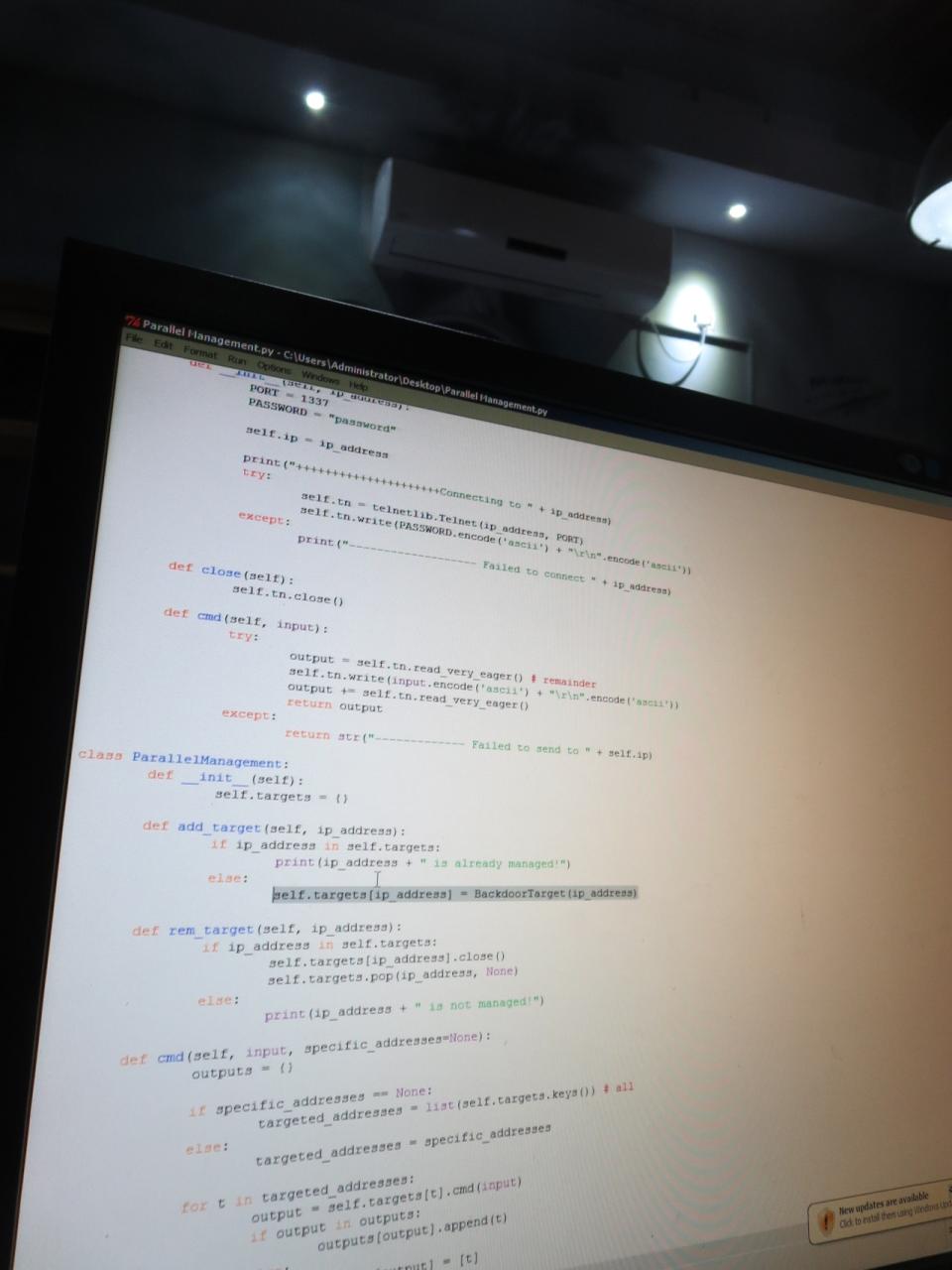

Lines of code on a monitor at CyberGym’s training facility.

Keeping the lights on

“Yes, we are in war,” said Israel Electric Corp. senior vice president Yosi Shneck at the start of a briefing at the company’s headquarters in Haifa. “If not war, at least a significant battle.”

At the low end, the almost-entirely-state-owned utility is subject to 4 to 5 million online attacks a month; at the peak of the “OpIsreal” campaign, that number approached 25 million. None have succeeded in taking IEC’s grid offline, although Shneck wouldn’t say how close they’d been.

“I don’t think we are smarter, but I am sure that we are unique in one thing: We are in a political situation that puts us in front,” Shneck said.

He did say that the nature of these attacks had changed, with fewer “distributed denial of service” attacks (in which massive numbers of computers are used to flood a targeted site with useless traffic) but more phishing attacks and attempts to tunnel into its networks with long-lived “advanced persistent threat” malware.

It’s important to remember that these attacks don’t all represent a Stuxnet level of danger. "Israel isn’t really high up on the level of state-on-state targets,” said Alex Crowther, cyber-policy specialist at the National Defense University’s Center for Technology and National Security Policy. “The top three most capable states are China, Russia and the United States, and none of them are going to target Israel.”

Against them, IEC has about 100 full-time cybersecurity employees and a 24-hour security operations center that monitors 16,000 events a second for signs of trouble, even if it’s just a door opened at a power facility.

The company has since spun off a security training operation, CyberGym, that challenges technicians to defend against attacks in a simulated power-plant control room on its campus in Caesarea.

If the “blue team” trainees lose control of their systems to the “red team” adversaries in an adjacent building (decorated with such hacker-ish art as a painting of Darth Vader and a stormtrooper in business attire), their lights will go out, an alarm will sound, and water can flood the floor.

I asked CEO Ofir Hason whether any U.S. utilities had sent employees to take its training. None have so far, he said, but the company is looking to open a location in the U.S.

That’s a good thing, observed one veteran of the U.S.-Israel technology relationship. “There’s a lot of knowledge you can bring here to the U.S. — experience, knowledge, training,” said Ronen Kenan, managing partner of Atlanta-based BizDev USA Israel. Alex Crowther concurred: “They have a lot to teach at the tactical level.”

Hacker art to motivate “red team” instructors at CyberGym.

Armed forces as farm team

Almost every Israeli working in cybersecurity shares the experience of compulsory service in the Israel Defense Forces. And many of them, in turn, come out of a particular part of the IDF, the ”8200” intelligence unit.

“It’s the Israeli version of the NSA,” explained Nir Lempert, a former deputy commander of the 8200 unit and now CEO of C. Mer Industries, a tech holding company — except that the National Security Agency can’t force people work there for the first few years of their careers.

“The unit can choose every year the best people,” Lempert said. “Now imagine that as the CEO of a company, I can choose the best of the best. This is a real privilege.”

As I talked to various security startups on the CyberTech show floor, the importance of 8200 and similar IDF units kept coming up.

"Service in the 8200 is a little like an MBA in the U.S.,” said Amit Rahav, a marketing vice president at the network-security firm Secret Double Octopus.

“The biggest driver for cybertech in Israel is the intelligence and military communities,” commented Dror Liwer, founder of the wireless-security company Coronet.

Having this sort of farm team has made it easier to decide who merits a job or an investment, said Jerusalem Venture Partners managing partner Gadi Torish: "It was fairly easy to track their references back to their intelligence units in the military.”

But that connection comes with some costs as well. “There is a sensitivity in the world to companies associated with their government,” said Gil Schwed, CEO of Check Point Software Technologies.

And because the government exempts Israel’s Arab citizens from conscription (a few of them volunteer anyway), some homegrown talent may never show up on the 8200’s radar. It’s unclear how well such ventures as a new technology accelerator in Nazareth to assist Israeli Arab startups can offset that.

Prime minister Benjamim Netanyahu speaks at CyberTech.

Top-down priority, top-down direction

Another facet of Israel’s approach that may be tough to export is its government-driven approach.

Israel Electric, for instance, is not only 99.85 percent government owned, but its cybersecurity regulator is the government’s Shin Bet security agency — the equivalent of having the FBI oversee a utility’s cybersecurity here.

Cybersecurity has been an official government priority since 2002, when then-prime minister Ariel Sharon set up a data-security unit in Shin Bet. (For reference’s sake, that was about the time in the U.S. when we officially realized we shouldn’t have let Enron treat the California power grid as its playground.) And that top-down emphasis will only increase.

Netanyahu made that point in his speech when he noted Israel’s creation of a national cybersecurity authority to direct efforts across private industry.

“We are coordinating all of our civilian cybersecurity efforts in one address,” he said. “Every single business, here is what we expect you to do in cyber.”

Gabi Siboni, head of the Institute for National Security Studies’ cybersecurity program, suggested that Americans wouldn’t like that approach: “I know that in your part of the world, regulation is a bad word, but I assume that in 10 years everything will be regulated.“

The government also invests directly in startups: The Office of the Chief Scientist in the Ministry of Economy has about $500 million a year, matched by private money, to put into promising companies.

Israel’s collective experience of being a New Jersey-sized country repeatedly attacked by its neighbors makes national security an easier priority for everybody to agree on. “If you have this small homogenous state which feels threatened, which has faced extinction… they are very focused,” Crowther said. “They are able to do cybersecurity stuff that we can’t do.”

A cluster of tiny houses at a CyberTech exhibit dramatizes the effect of an attack on the power grid.

What’s to share?

All this experience and attention was not enough to stop Israel’s electric authority from being hacked, nor did it stop such earlier intrusions as the 2014 compromises of three Israeli defense contractors or a successful malware attack in 2012 on Israel’s police department.

And while some tech figures here may sound a little cocky sometimes — “We have an amazing opportunity here as Israel, because 95 percent of those companies worldwide don’t know anything about cyber,” said CyberSpark Initiative CEO Roni Zehavi — others noted that Israel didn’t build this itself.

“The multinationals, primarily the U.S. multinationals here, are part of our revolution,” said JVP founder and parliamentarian Erel Margalit, a Labor member of the Knesset. “We needed the U.S. management culture and needed venture capital to kick ass.”

The U.S., in turn, could learn a thing or two from the seriousness Israel brings to online security, even if its state-centric approach isn’t likely to fit here. Or, as IEC’s Shneck put it, sounding perhaps a bit paranoid but speaking truth, “The most risky moment for an organization is when they feel protected.”

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.