The unlikely staying power of the humble floppy disk

When Sony stopped manufacturing new floppy disks in 2011, most assumed the outdated storage medium – of which there is only a finite, decreasing number left – would die off.

But 15 years later, there are still those who "hold on to floppies", said Techspot, whether for "nostalgia-fuelled pleasure or necessity".

Although from a "different era of computing", to this day floppy disks have an "enduring appeal", said the BBC. Some people are "in love with them", while around the world there are those who "depend on them".

'Floppy disks just work'

"Few things bring a smile to the face of long-time techies over 30 (or thereabouts) quite like the mention of floppy disks," said Techspot.

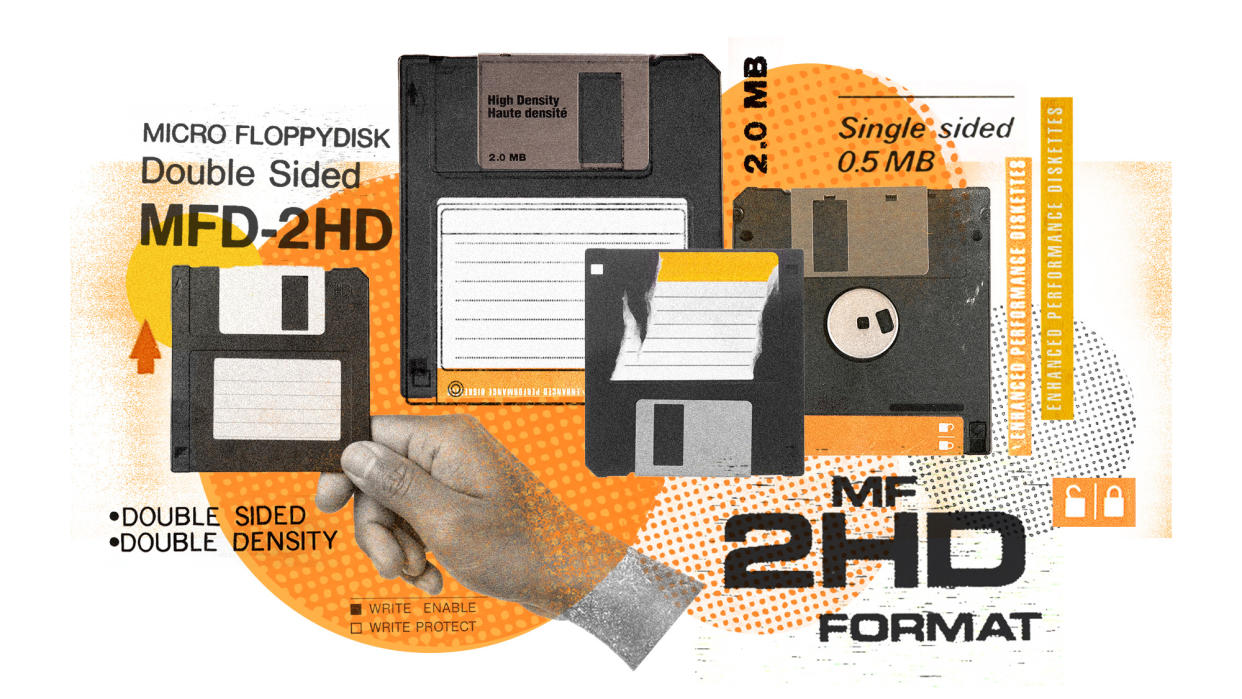

The "floppy" emerged in around 1970 – so named because you could bend the original disks without breaking them. For about three decades, they were the main way people stored and backed up computer data.

But by the 1990s they had largely fallen out of fashion, as technological advances like memory sticks and CDs, and later cloud storage, could store a far larger amount of information. The floppy was "immortalised" as the "save" icon on most computer applications, said the BBC.

Now, floppy users are "slowly dying out", and the finite number of disks in the world is "gradually dwindling". But various "legacy industrial and government systems" around the world still use them, and some city transport systems even run on them. Some Boeing 747 aeroplanes use floppy disks to load "critical software updates" into their navigation computers.

In the 2010s, US officials were discovered to still be using floppy disks to manage their nuclear weapons force. In 2022, Japan's digital minister "declared war" on floppy disks and other retro tech like CDs and mini-discs, after a committee discovered nearly 2,000 areas in which businesses were still required to use them.

For a lot of people, "floppy disks just work", said the BBC. Why spend money upgrading technology that's "basically fine"?

A 'powerfully weird little niche'

Although floppy disk music "peaked" in the 2010s, it's "still going strong" in the 2020s, said The Verge. In the 2020 category, online music release catalogue Discogs.com shows a "healthy 500-plus floppy releases", more than the documented number released in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s combined.

The floppy is a "quiet mainstay in DIY-driven media", wrote culture reporter Alexis Ong, especially in the so-called "lobit" subculture, which celebrates low-bitrate music "as a form of art and practicality".

While physical media are being "miserably, myopically phased out of everyday retail", the "powerfully weird little niche" of floppy music is still "alive and kicking".

Perhaps their appeal can be explained because "we've moved a little closer to their impending extinction", said Ong. Floppies "aren't made for long-term storage", which forces users to "confront the transience of art and information in the face of time and decay".

Maybe "one out of 100 floppies goes bad for me", musician and disk hobbyist Espen Kraft told the BBC. That's despite careful storage in a dry, non-humid environment. Storing collections in an attic or cellar risks a far higher rate of corrupted disks. Meanwhile, with nobody manufacturing the disks any more, computer systems that read them will only become more difficult to maintain.

The floppy is also running on "borrowed time", said Ong. Tom Persky, who runs floppydisk.com – the only remaining floppy seller – supposedly has about half a million disks in stock. The disks are also "pretty expensive" to buy, said Thomas Walskaar of Floppy Totaal.

So how to explain their enduring popularity? Perhaps floppy disks are "perfect reminders of how violently smashing bytes together on a thin, vulnerable plastic/magnet sandwich is still one of the most punk things you can do as a musician", said Ong.

Or, suggests Floppy Totaal's Niek Hilkmann, perhaps the appeal is more symbolic: a floppy "shows us that nothing is eternal and everything that seems to be very vague or obscure, especially in the digital realm, isn't that at all".