Ukraine Is Deploying This Classic American Missile, Bringing a Cold Warrior Back to Life

Ukraine’s military has shared the first image of its newly-operationally-deployed MIM-23 Improved HAWK (or ‘I-HAWK’) air defense battery. The American medium-range air defense system, identifiable by its distinctive M192 three-rail launchers, was widely deployed during the Cold War and continues to serve in many countries more than 60 years after it was first deployed. The missile seen in the photo bears marking indicating that it was manufactured in 1981.

In the fall of 2022, Spain announced that it would donate a battery of six launchers—which arrived that December—and followed that donation with 12 more launchers. The United States, meanwhile, furnished supporting radars and control systems for two HAWK batteries, as well as compatible missiles and missile-refurbishing services. Sweden has also contributed key hardware to enable the activation of Ukraine’s HAWKs.

Reflecting the military’s love of forced acronyms, ‘HAWK’ is ostensibly an acronym for Homing-All the Way Killer. This system uses Semi-Active Radar Homing (SARH), in which a passive seeker on the missile homes in on the reflected radar waves of an aircraft ‘illuminated’ by a spotlight-like active radar on the ground.

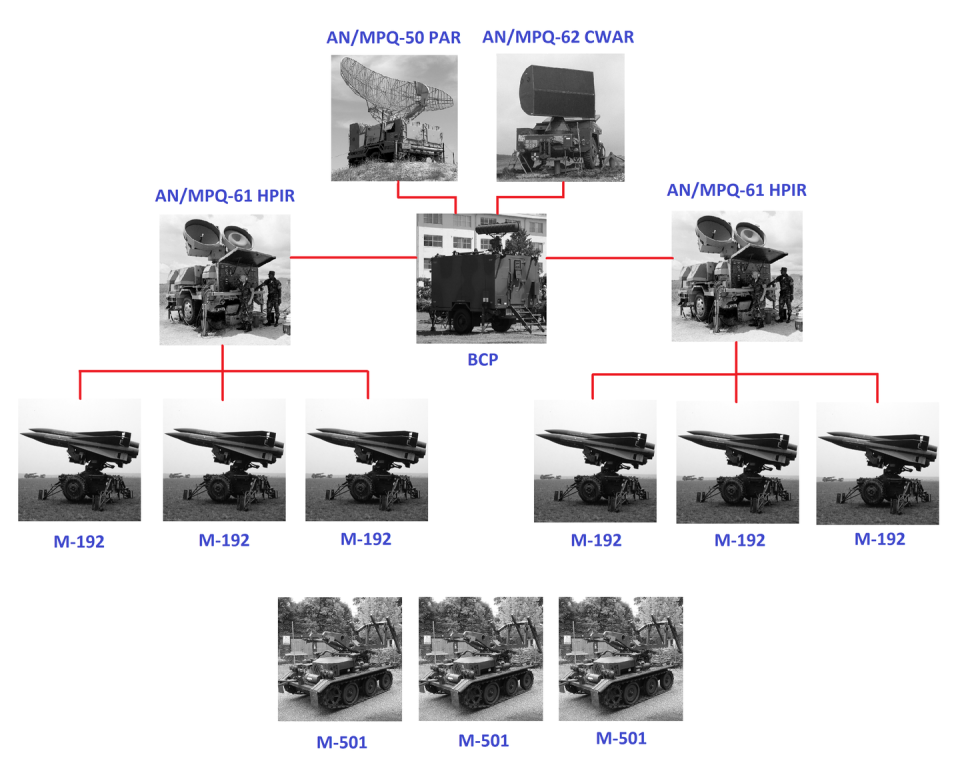

The battery donated to Ukraine is the ultimate Phase III model—typically consisting of two rotating search radars (AN/MPQ-50 PAR and AN/MPQ-62 CWAR) to initially detect aircraft approaching at medium-to-high and low-altitude respectively, and six launchers mounting three missiles each. When targets are acquired, they’re lit up by two AN/MPQ-61 illuminator doppler radars known as HIPIRs, which are used to guide the missiles. HIPIRs incidentally pose a radiation risk to nearby personnel when oriented downwards.

Rounding out each battery are six 60 KW generators and three M501 missile-loading tractors that carry a total of 36 missile reloads.

Though Ukraine first received HAWKs in December of 2022, it was ten months before the first video showing kills by one of the launchers was shared by the country. The targets—visibly destroyed over water (one of them fairly close to the launcher)—are believed to be amongst 13 Shaheds and one Kh-59 missile destroyed that day, mostly near the port of Odesa.

A US 🇺🇸 MIM-23 Hawk Air Defense System shooting down likely Russian fired Shahed Kamikaze Drones overnight today in Ukraine 🇺🇦 pic.twitter.com/FR4K3lXUKd

— Ukraine Battle Map (@ukraine_map) October 23, 2023

It’s possible that the delay reflects a quiet upgrade of Spain’s donated HAWK systems to the latest HAWK XXI configuration, which uses the modern AN/MPQ-64 phased array radar also employed by Ukraine’s donated NASAMs air defense batteries.

However, imagery of the Ukrainian HAWK battery itself has been lacking, perhaps to maintain ambiguity regarding its location and the configuration of its radars. The first image has been blurred to obscure clues to its location, and only shows a loaded M192 launcher covered with camouflage netting, not the battery’s various radars.

I-HAWK missiles all measure 370 millimeters in diameter and weigh nearly three quarters of a ton. Their M117 rocket motors burn for 26 seconds, boosting the missile to over 2.4 times the speed of sound and achieving a maximum intercept range of 22 miles (or, some sources claim, 26-31 miles). The rocket can reach as high as 60,000 feet, sufficient to reach nearly all manned aircraft. However, HAWKs cannot engage targets closer than one mile away.

The dated HAWK is unglamorous compared to cutting-edge Patriot air defenses that Ukraine has used to shoot down ostensibly unstoppable hypersonic missiles and destroy a half-dozen advanced jets over supposedly safe airspace.

But the Patriot’s multi-million dollar missiles can only go so far when Russia surges more than a hundred drones and missiles for the larger-scale air raids of its Winter strategic bombing campaign. Ukraine needs quantity, not just quality—particularly as it will inevitably exhaust supplies of old Soviet air defense missiles.

Thus, the HAWKs are a welcome addition to Ukraine’s arsenal—particularly as they have proven more than capable with a historical tally of roughly 100 manned aircraft kills.

HAWK, America’s Cold War Air Defense Missile

Development of the HAWK surface-to-air missile began in 1952 and was ultimately split between Northrop (for the ground-based systems) and Raytheon (for the missile). It was in both U.S. Army and Marine Corps service by 1960, and became the mainstay of the Pentagon’s Cold War ground-based air defenses, which were forward deployed in Germany, Japan, and South Korea.

HAWK battalions were also stationed in Florida during the Cuban Missile Crisis and deployed to Vietnam in 1965, where they protected bases at Bien Hoa, Chu Lai, Da Nang, Saigon, and Na Trang. Though they lost missiles, radars, launchers, and personnel to Viet Cong infiltrators and artillery attacks, they never ended up firing at North Vietnamese aircraft.

Instead, the first HAWK systems to fire in anger were those exported to Israel in 1965. During the War of Attrition, they shot down at least five Egyptian supersonic Su-7 attack jets, several MiG-17 and MiG-21 fighters, and an Il-28 jet bomber.

In the subsequent 1973 Yom Kippur War, Egyptian air strikes often targeted HAWK batteries and managed to knock two of them out. In turn, Israel’s 12 HAWK batteries claimed to have downed 22 Syrian and Egyptian aircraft out of 25 attempted engagements (each involving two shots fired to improve hit odds).

A Marine Corps study of air defenses in that war concluded that Israel’s HAWKs demonstrated a good success rate, but weren’t able to outright repel or deter Egyptian airstrikes and helicopter-borne commando raids due to rearward positioning, inability to detect low-flying aircraft, and rules of engagement designed to reduce friendly fire risks.

The original ‘Basic HAWKs’ indeed had a high technical failure rate, poor predicted hit probabilities (about 56%), and limited low altitude interception capabilities. But in 1972, the MIM-23B Improved HAWK—or I-HAWK—entered service with new missiles, radars, and fire control system.

Furthermore, for two decades, I-HAWK received continual upgrades known as Phases I through III (with rounds designated MIM-23C through MIM-23M) that enhanced its range, blast radius, resistance to enemy jammers, and ability to sort out ground clutter when engaging low-flying aircraft. Enhancements included a new 10x magnification thermal/electro-optical sight for visual-range engagements and the replacement of vacuum tubes with solid-state electronics. Predicted hit rates rose to 85%.

The final Phase III models introduced a new ‘fan beam’ radar mode—this allowed one battery to engage up to 12 targets simultaneously and enhanced anti-ballistic missile capability from revised warheads with ‘larger-caliber’ shrapnel.

Marine Corps I-HAWKs deployed during the 1991 Persian Gulf War nearly fired in anger when they targeted two Iraqi Mirage F1s attacking a Saudi oil terminal at Ras Tanura, only for Air Force F-15C fighters to beat them to the punch. The Army finally shelved its HAWK batteries in 1994. The Marine Corps held on to its HAWKs through 2002 before entirely retiring its medium-range air defenses.

The I-HAWK instead experienced its most prolonged combat use at the hands of Iran. In 1974, two of the 24 I-HAWK batteries acquired by the country (along with one Rapir missile battery) deployed into Iraqi Kurdistan and reportedly downed 18 Iraqi aircraft attacking Iran-backed Kurdish rebels.

However, their true legacy was written in the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, during which they accounted for the demises of roughly 40 Iraqi jets—including Su-22, MiG-23, and even two Tu-22 Blinder supersonic bombers. They also, however, downed several friendly F-4 and F-14 fighters by accident.

Dubbed ‘Death Valley’ by Iraqi pilots, Iran’s HAWKs disrupted and deterred numerous strike formations, sometimes compelling aircraft to ditch weapons and abort missions. HAWK batteries contributed to heavy Iraqi aviation losses in Iran’s recapture of Khorramshahr in 1982, the First Battle of al-Faw in 1986, the battles for Khalq island (despite several lost to Iraqi air strikes), and Iraq’s counter-bombardment of Iran’s failed Val Fajr I and Karbala 5 offensives.

Reportedly, early Soviet SMALTA and TAKAN jamming systems used by Iraq were ineffective against I-HAWKs, though the later SMALTA-5 proved more effective. Iran also adapted its F-14 Tomcat jets to carry modified HAWK (known as Sedjils) for long-range air-to-air combat and scored several kills. Iran’s appetite for HAWKs was such that the Reagan administration illegally sold 238 HAWK missiles to Iran as part of a covert scheme to (also illegally) fund Contra rebels in Nicaragua.

MIM-23 saw action in several other conflicts. In 1982, an Israeli HAWK downed a notoriously fast Syrian MiG-25 Foxbat flying at high altitude over Lebanon. When Iraq invaded Kuwait, Kuwaiti HAWK batteries allegedly shot down as many as 22 Iraqi airplanes and one helicopter.

A French HAWK unit deployed to Chad during its struggle against Libyan invasion claimed an unusual kill in 1986, downing a big Tu-22B jet that was bombing its position from directly overhead. More recently, in 2020, several Turkish HAWK systems deployed to Al-Watiya airbase in Libya were apparently knocked out by an air strike of either the LNA faction or its foreign allies.

Many countries still operate HAWK batteries. Spain first acquired four MIM-23A batteries from the U.S. in 1965. These went to its 74th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiment in Seville and Cadiz, complementing its armament of 40- and 90-millimeter flak guns. Then, in the 1990s, Madrid acquired two retired U.S. I-HAWK batteries.

Those units remaining in Spanish service have been upgraded to a HAWK XXI variant, which replaces the system’s rotating search radars with the modern AN/MPQ-64 Sentinel phased array radar, a new Norweigian-built command center, and ballistic missile defense capability.

The HAWK lands in Ukraine

As the HAWK’s launchers and radars are trailer-based, the MIM-23 is less mobile than most of Ukraine’s Soviet medium-range air defenses. That means it may be more vulnerable to air defense suppression attacks both from specialized home-on-radar missiles and general strike assets (glide bombs, Lancet or Shahed kamikaze drones, and ballistic missiles). Such risks may be partially mitigated by keeping HAWK units away from the frontline in a rear-area defense role.

Following heavy early-war losses to Ukraine’s Buk systems, Russian warplanes rarely venture much within range of Ukraine’s medium-range air defenses. While maintaining deterrence of manned aviation is intrinsically valuable, Ukraine’s HAWKs will mostly engage in swatting at Russian drones and missiles.

Admittedly, drones like Shahed or Lancet are likely between one-fifth and one-tenth the price of the HAWK’s current $250,000 price tag. But sometimes, cheap and gun-based defenses simply aren’t in position to stop attacks. In those cases, its better to expend a MIM-23 missile than something newer and more expensive.

Furthermore, even the original MIM-23A HAWK was tested successfully against ballistic missiles, and the MIM-23K or J variant missiles boast special warheads for defeating such highly challenging targets. Notably, the U.S. Army has already tested integrating HAWKs into its Patriot air defense networks, enhancing both system’s effectiveness. And HAWK missiles are cheaper than any cruise or ballistic missiles they might potentially intercept.

The HAWK’s potential scalability is also a vital attribute, as the U.S. has built over 40,000 MIM-23 missiles since 1960, along with hundreds of launchers. Several major operators of the system have recently—or will soon—retire their batteries. That means there are several possible avenues for Ukraine to scrounge additional HAWK systems or components.

Indeed, the U.S. is allegedly arranging purchase of around 100 I-HAWK launchers from Taiwan as it retires the system for transfer to Ukraine. If furnished with sufficient missiles, an ancillary fire control system, and a radar system, these could theoretically allow Ukraine to standup around 16 more batteries (plus change).

However, some retired HAWK systems (including those of the U.S. and the 17 I-HAWK batteries operated by Israel) have been found to be unusable without major refurbishing due to poor storage conditions. And with the war in Ukraine serving as a gruesome warning of the importance of deep air defense inventories, some HAWK operators like Egypt, Greece, Romania, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey might prefer to hold onto their HAWK inventory... just in case.

Given Russia’s frenetic efforts to produce new missiles and scrounge up old munitions to sustain attacks, HAWK systems represent an important avenue for sustaining Ukrainian air defenses in a conflict that’s turning out to be more of a marathon than a sprint.

You Might Also Like