This Week In Space: Mining Asteroids, Reusing Spacecraft, and Orbiting Venus

In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) makes all the rules about air travel. But what about space travel? It turns out that Congress has actually barred the FAA from setting rules for it. A new law will now keep it that way until at least 2023.

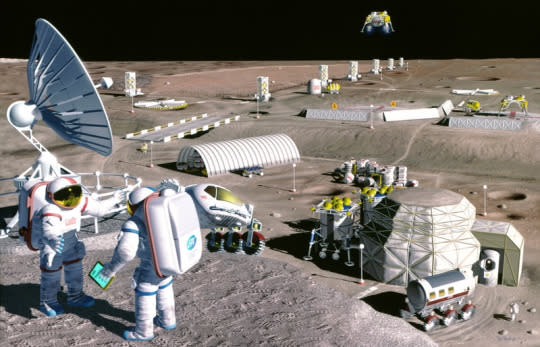

Perhaps more interestingly, the same law allows for “commercial recovery of space resources” — meaning that if you could fire a rocket, go to an asteroid, and dig up a bunch of valuable metals, they’d belong to you. Right now the cost of going into space is the limiting factor in making a profit by mining asteroids. But it’s definitely possible that it will become cost-effective sometime this century.

And once it does, there’s plenty of valuable stuff floating around out there. Asteroids contain significant supplies of many elements that are quite rare on Earth. There’s also stuff that’s freely available here on Earth but quite valuable to people in space: drinking water, oxygen, and elements to make propellant (so you could refuel your rocket in space rather than carrying a full round-trip’s worth of fuel with you).

The new law also officially extends the life of the International Space Station through 2024. After all the years and Space Shuttle missions spent building the ISS, it’s hard to imagine that it might be shut down. But it is already 15 years old. And even this new lease on life might not mark the end for the space station: There’s been some talk that it might last through 2028. And because it’s modular, elements of the space station could be swapped in and out, either keeping it alive indefinitely or recycling the parts for reuse in a new station.

Recycling rockets

Jeff Bezos’s somewhat secretive space company Blue Origin made news by launching a rocket into space and landing it back at the company’s Texas spaceport. The video has to be seen to be believed, though it uses technologies that we’ve used in landing probes on other planets before.

(Video: Blue Origin)

Blue Origin has beaten its competitor, SpaceX, to the punch: The latter has tried to land its Falcon rocket on a platform at sea a couple of times, but hasn’t quite made it yet. SpaceX is now talking about landing one of its rockets at Cape Canaveral instead of in the ocean.

The big deal here is that reusable rockets make access to space much cheaper. If every commercial airliner had to be thrown away after a single use, there would be no commercial airline industry. Re-using not just the spacecraft but the rockets that shoot it into orbit is a key to making the getting of stuff (including people) into space a practical possibility.

Japanese space drama

It’s a big week for the Japanese space agency, with two different spacecraft in action this week. One of them is providing pretty pictures while the other is providing some high drama.

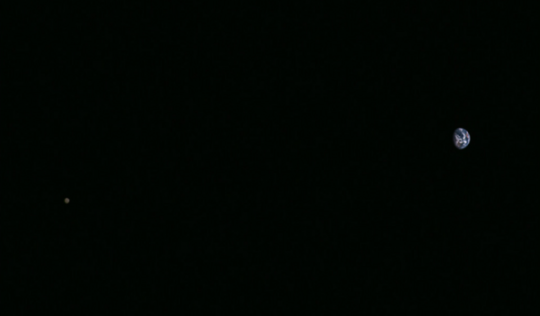

The pretty pictures come courtesy of Hayabusa 2, a craft that’s headed to an asteroid to examine it and (speaking of mining asteroids) collect some samples and return them to Earth. As a part of its orbital maneuvering, Hayabusa 2 flew past Earth this week and was visible in the sky over Japan. On the way, it snapped a spectacular picture of the Earth and the Moon. That’s us! Everybody wave.

Moon (left) and Earth (right). (Photo: JAXA)

Then there’s Akatsuki, the Japanese probe that was destined for Venus in 2010 when its thrusters failed and it sailed on by. After a whole lot of working the problem and examining what was wrong with the craft, the space agency figured out that it could use the Akatsuki’s secondary thrust system to nudge the craft into Venus’s orbit. Over the last year, the agency has been been making the necessary — and subtle — orbital maneuvers to get ready.

On Monday, Akatsuki faces its moment of truth: The damaged craft will fire its Reactor Control System thrusters one more time and attempt to insert into Venus orbit, where it can collect data on Venus’s atmosphere. The result won’t be quite what was originally intended — there’s only enough propellant to get Akatsuki into a looping orbit where it will approach Venus every eight or nine days — but it’s better than nothing. If the Japanese space agency can pull it off, it’ll be a pretty great save.