Santa Cruz Guitars' Richard Hoover explains the science of vintage wood and guitar tone

Some things improve with age. Guitars certainly sound better over time, particularly acoustic guitars, because it’s literally all about the wood. This is a subject Santa Cruz Guitars Company captain Richard Hoover knows all too well.

When we last spoke to him, Hoover was crafting the company’s stunning Vault Series from some of the most prized ancient wood on the planet for release at the NAMM show. We had chance to catch up with him again at the event for a follow-up discussion about old-growth woods. Here’s what he had to say.

Why does old wood sound better?

“The reason to a large degree is that the sticky resins within the wood don’t harden from the evaporation of moisture. You remove moisture when you dry wood out, but there is still sticky stuff left in there.

“Let’s say a commercial mass-production guitar was made from a piece of wood cut from a tree, dried carefully and stabilized, but the resins remain sticky. It then goes into a guitar within less than a year, maybe even six months. When string energy goes through, it’s resisted by sticky stuff.

“Every minute when it’s living, the tree’s sap has a low viscosity and flows freely to deliver nutrition throughout the tree’s structure. As soon as the tree dies, the sap begins a process of polymerization, like glue drying. Over time it becomes crystal-like. Give the guitar 10 years, 50 years, 100 years, and it progressively becomes more resonant and sounds better.

“The resins harden no matter whether the wood is underwater, in outer space or in a master luthier’s violin, because the process is not dependent on oxygen – it’s the chemical change that hardens the resins and improves the tone of the instrument.

“Why wait when we can start with more-resonant old wood? We can do that working at our scale of less than 500 custom guitars per year, whereas it would be difficult or prohibitive for a large production company.”

What’s better about sinker wood that has been submerged in water for a significant period of time?

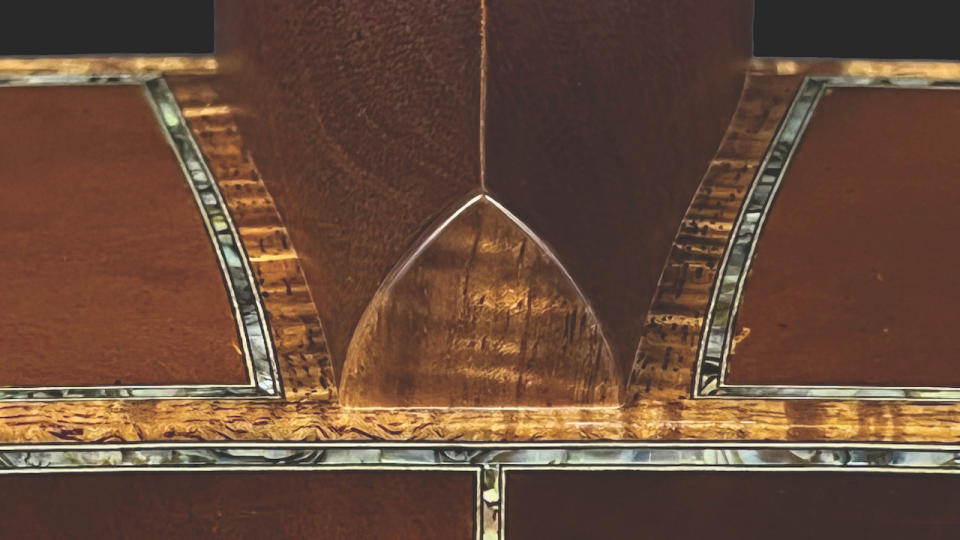

“Let’s use the redwood from the Vault Series H13 1854 as our example. There are two kinds of old-growth reclaimed redwood in nature. In this case, there’s the sinker that would have tumbled into the San Lorenzo River, got lodged and stayed there for a few hundred years; and there’s buckskin, which could have been a tree standing right next to it but didn’t quite make it in the river and stayed on the bank.

READ MORE

“They’re both going to go through the same process of polymerization and sound better over time. I haven’t experienced a qualitative tonal difference, but the cosmetic difference is very apparent. The buckskin is generally lighter while the sinker, particularly this Purple San Lorenzo sinker redwood, is much darker because of the mineral content that would have leached in and oxidized over years.”

What’s the first step you take to ensure bringing out the most potential beauty?

“The guy I got this from is like an artisanal lumberjack. He doesn’t set it up in a saw and slice off the pieces like almost everything else. In the old days, like in the violin tradition, you would split it. A tree grows like a bundle of soda straws. With wind and gravity, those will move around.

“When you cut a board out with a saw, those holes are coming out everywhere. They’re not straight up and down because the grain is going in and out everywhere. But if you split it, the board comes out right on. It separates the straws, and you get perfectly uniform ‘run out.’”

For more info on Santa Cruz Guitars and its lineup of instruments, visit the company's website.