How tech companies are propelling the environmental movement, and why it's time to do more

Due to their influence, funds, and will to act, tech companies have emerged as key players in the environmental movement. Here's what we think they need to do to take it to the next level.

Loudoun County, Virginia, is home to more than 4.3 million square feet of data centers and claims that 70% of internet traffic flows through it every single day. It hosts the servers of many major tech companies, and because of that, it has enormous influence on the world -- even though hardly anyone knows its name.

But the county -- its data centers, its people, its economy, its land -- is still in the hands of the coal industry.

Clean energy has shown renewed signs of progress in 2014, and it has energized environmentalists, technologists, social entrepreneurs, and educators alike. This year, the tech industry in particular has received a lot of praise for its work toward renewable energy.

Photos of solar panels on the roofs of giant corporate buildings, vast wind farms sprawling across the desert, and massive hydropower plants along the coasts are widely circulated. Startups in Silicon Valley and around the world have focused efforts on solving problems facing the energy sector such as battery storage, energy transmission, and big data analytics. Companies have become more transparent about their environmental practices and scaled up their efforts in corporate social responsibility.

But the truth of the matter is, large scale improvement -- like significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and the slowing of climate change -- doesn't happen when tech companies narrowly focus on their own operations and build their facilities in already environmentally progressive states like California or Nevada.

It happens when they get involved with states like Virginia.

Dominion Energy is the utility provider for Virginia, and coal and natural gas accounted for 98% of its electricity in 2013. Only 2% was from renewables. The state of Virginia is a leading coal producer; about 4.5% of US coal production east of the Mississippi River in 2012 came from the state. And Norfolk, Virginia, America's largest coal export facility, processed more than 38% of US coal exports that year, according to the Energy Information Administration.

So if it's true that the majority of internet traffic flows through the servers in Loudoun County, and the majority of tech companies still rely on coal, that means that the majority of the internet continues to be powered by finite fossil fuels.

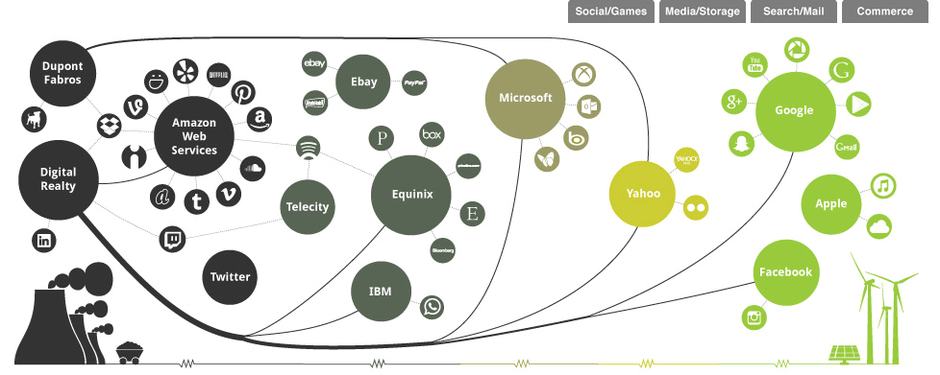

According to Greenpeace's most recent report, the cloud consumes as much energy as what would be the world's sixth largest country. After Greenpeace began calling out the world's largest tech companies a few years ago, Apple, Google, Facebook, and others vowed to power their data centers with 100% renewable energy. Apple and Facebook have built new data centers that run on 100% renewable energy, and Google is more than a third of the way to that goal.

But Amazon, the other tech giant, remained silent until several weeks ago. The company finally announced in a low-key statement on its website that Amazon Web Services (AWS) -- its cloud computing division -- has a "long-term commitment to achieve 100% renewable energy usage for our global infrastructure footprint."

AWS servers host Netflix, Pinterest, Spotify, Vine, Airbnb, and many other websites. According to David Pomerantz, media officer for Greenpeace, Amazon operates at least 10 data centers in its "US-East" region, and its largest is in Northern Virginia.

"We don't know exactly how much electricity Amazon uses there, since the company still hasn't published that data, but it's safe to say that it's a lot. We and other analysts have estimated that over half of Amazon's servers are in this region," he said.

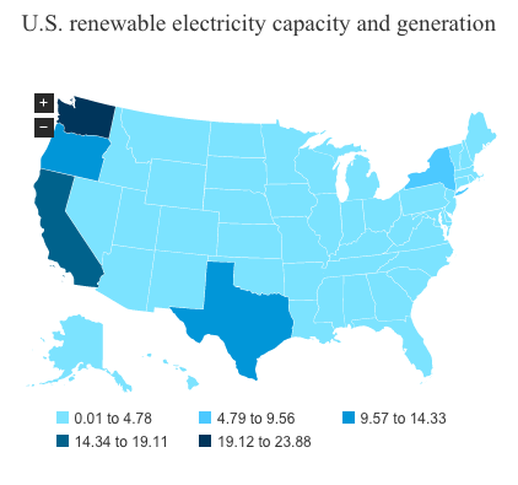

Image: EIA

The transition to renewable energy will affect many people, because fossil fuels are embedded deeply in Virginia's culture and economy. But it's an issue that will eventually surface in every state as the US and the world move forward to tackle energy sustainability and climate change.

Economic effects, difficulty of implementation, and fear of the unknown are just some of the reasons lawmakers stalemate over environmental policy changes and why they become so politicized. But now, tech companies are starting to fill the gaps that the government won't, while serving as examples of how relatively fast and cost-effective it is to make these changes.

Where governments lacks speed, the tech industry moves at a staggering pace. Utilities lack efficiency; technology companies are obsessed with innovation. Many of these communities lack funding or people to effect change; tech giants have both. And where environmental organizations cause polarizing debates, tech companies remain mostly neutral.

Amazon has a choice to move forward with its pledge -- and it will involve, as most progress does -- getting entangled with state and federal laws, the utility industry, fossil fuel companies, and various stakeholders.

Of course, the company's decision in Loudoun County is only one example in this larger picture of progress. But it's an important one. Amazon, who declined to comment on its commitment to use renewable energy in its data centers, is now at a very public crossroads.

Because it has such a footprint on the east coast, where coal reigns king, it has a chance to make a difference in the way Loudoun County is powered -- and maybe, how renewable energy is addressed in the future.

"Amazon could do any number of things, including pushing Dominion to improve that offering, pushing them to invest in more renewable energy, buying renewable energy from another provider, or pushing state policymakers to tear down some of the barriers to renewable energy growth in Virginia," said Pomerantz. "What it really can't do, if it wants to make good on its new 100% renewable energy pledge, is sit still."

State of affairs

In 2013, renewable energy accounted for about 10% of total US energy consumption and 13% of electricity generation, according to the EIA. And at the state level, there isn't much preparation either. A study earlier this year from Georgetown Climate Center showed that less than half of US states are preparing for the looming effects of climate change.

This year, President Obama finally addressed climate change by instituting the first ever federal ruling, the Clean Power Plan, to cut carbon emissions by 30% under 2005 levels by 2030. But recently, the EPA has discussed an extension for the ruling after much lobbying by utility companies during the past few months.

One of Google's wind farms.

Image: Google

Greenhouse gas emissions increased at their fastest rate in 30 years in 2013, according to the World Meteorological Organization. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that January to October of 2014 had the highest global temperatures on record.

Addressing climate change is a global conversation, and with the rapid growth of technology around the world, it is becoming even more urgent, public, and connected.

According to the US Census, almost 75% of the US population has access to the internet. Over half of American adults use their cell phone to go online, according to Pew Research.

China is expected to have 200 million new internet users by 2015, and companies such as Amazon are planning to open China-based data centers to meet that demand. In 2011, between 1.5% and 3% of energy generation in China went toward powering the internet. And although people in emerging markets are largely offline, the internet, particularly on smartphones, has seen tremendous growth, and people who get it integrate it into their lives very quickly.

The tech industry is starting to use that power, money, and growth to affect positive change in areas where government efforts are stagnant. That's not necessarily driven by altruism, of course -- it's just good business. But since the tech industry is driven by competitiveness, these clean energy moves are becoming effective in building a movement.

"In addition to the environmental benefits, we see renewable energy as a business opportunity," said a Google spokesperson. "Perhaps most importantly, we look for scalable solutions that can have the highest possible impact. It's great if we solve a problem for ourselves, but we also want to be looking for opportunities to directly address problems that limit the growth of renewable energy. Over the years we've been open and shared our approach to renewable energy with the industry (and the public) in a series of white papers, blog posts and events."

Google is also drawing a few lines in the sand. In 2014, the company withdrew from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and executive chairman Eric Schmidt said ALEC was "just literally lying" when denying climate change. Microsoft withdrew its support from ALEC back in 2012.

However, it's not only the tech behemoths who are standing up for the environment. Salesforce, Box, and Rackspace are also leading the way in environmental responsibility, committing to 100% renewable energy, setting attainable goals each year to reach that point, and making sure they're transparent about it.

"I do think that has a huge effect," Pomerantz said. "It's a big effect on the business community, a lot of people who maybe don't care what Greenpeace has to think about climate change, they're more impressed [with that]."

"Economic influence will be a bigger driver of expanding clean energy than just environmental well-being." Matthew Stepp, CCI

This momentum throughout the industry -- and particularly, the leadership shown by big tech companies -- has potential, said Matthew Stepp, executive director of the Center for Clean Energy Information. And the action from those companies shows that it just makes economic sense.

"It's absolutely true that the economic influence of companies like Amazon will push some of these states to act more flexibly when it comes to their energy mix because it's easy for Amazon to move elsewhere that is more amenable to its sustainability demands," Stepp said.

Ultimately, he said, he believes states will make it work because it means more jobs within their borders. Whether that flips a state to adopt very aggressive clean energy policies remains to be seen, though. Many of the states will probably be able to accommodate renewable energy practices without implementing really aggressive policies like carbon pricing or portfolio standards.

He added: "I think that goes to show that economic influence will be a bigger driver of expanding clean energy than just environmental well-being."

The longstanding movement

Technology and nature have been at odds throughout history. But tech companies now have the knowledge and resources to effect change -- so they now have a choice. They are no longer dependent on one source of energy, and most of the time, they aren't dependent on the government.

"Flexible policy is critical as well as continued support for technology development that opens up new opportunities for these companies to offer more innovative, efficient technologies, as well as reduce their carbon footprint even more," Stepp said.

Apple's data center in North Carolina.

Image: Apple

The environmental movement has been viewed as a left-wing liberal push since the radical events of the 1960s. The iconic image for most people is probably of a dirty protester chained to a tree, or lying in front of a bulldozer. It's the movement that spawned Greenpeace, PETA, NRDC. It's the movement that called dramatic attention to climate change and global warming, that made them seem like they were optional to believe. But it has successfully served the public good by advocating for cleaner water, expansion of protected lands for parks and forests, safer working environments for coal miners, preservation of biodiversity, and more.

Awareness around the need for an environmental movement started in the 19th century, after the Industrial Revolution, when coal burned at an unprecedented rate in major cities because of vast, rapid growth and innovation, and pollution from factories poured into the air, and chemical waste flowed into water sources. The first environmental law -- the Alkali Act -- was passed in 1863 in Britain to regulate pollution.

Early on, radical environmental ideals were pushed by individuals and organizations. They banded together to stop coal pollution, to conserve natural lands, to safely sanitize cities. In the late 19th century, literature on the subject by Henry David Thoreau, and the establishment of the Sierra Club by John Muir, ignited the movement.

It wasn't until the 1950s that the movement truly started to take off in the US. As technological innovation progressed, people began to realize it often came at a cost to the natural world. So began the backlash against chemical companies. The Nature Conservancy was established in 1951. The Air Pollution Control Act was passed in 1955. Carbon dioxide levels raised to 300 parts per million during the decade, and NGOs like the Sierra Club started to gain recognition for their protests.

Then, in 1962, it got much more serious. Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, and it became the catalyst for the modern environmental movement. Largely because of her work, DDT -- which had been considered a miracle of modern technology -- was banned in 1972. Perhaps the most important aspect of Carson's book, though, was her warning against technological innovation -- that humans should not ruin nature with their progress. But she didn't call for federal regulations, because the government could be in the hands of the industries that were destroying the planet. She wanted the people to understand those processes and their consequences.

"For the tech sector to really leverage all of its influence, it needs to impact government decisions as well." David Pomerantz, Greenpeace

Fast forward to today: the current grid system is about to be turned upside down, because of renewable energy technologies. People, companies, and communities now have the opportunity to generate their own power by installing solar panels, and they don't want utility companies to make all of the money off of it.

Technological innovation -- and by default, tech companies -- have a big role to play in this conversation, because no one has quite figured out the formula yet.

"New business models will be at the heart of transforming [and] accelerating adoption of renewable energy at scale. Right now we have a lot of big renewable deals where one large entity creates their own private energy, or deals that only work when there are incentives," said Melissa Gray, senior director of corporate social responsibility for Rackspace. "Not everyone can do that, so we need more options for different sized players and that make sense long term to scale out."

The risk of too much talk

Earlier this year, Pew Research asked participants of a study if they thought "environmentalist" described them. More than 40% of respondents agreed -- with the exception of millennials. Only 32% of them said yes. NPR looked into the phenomenon and found that millennials (18 to 33 year olds) felt like the term has been corrupted or too politicized. Many of them want to be known for doing good for the environment, and supporting those causes -- but they're not committed to the label.

However, one thing millennials -- and really, most people in general -- are fairly committed to is their favorite technology companies. The people who will wait in line for three days at the Apple Store will probably also back Tim Cook's bold stance on the environment.

Getting involved with the government is important, Gray said, but rallying fans can be just as critical. And that has proven true. Tech companies, though they may be scolded for their fickle privacy policies, pointless software updates, and expensive tools, are generally well-trusted by the public to be progressive and do good for the world.

"Rackspace opted to define an energy policy to rally 'Rackers' around how we thought about it and our resultant actions," Gray added. "We continue to work internally to define our advocacy strategy. We'll be doing more in 2015 in these areas."

Environmental organizations like Greenpeace have always been watchdogs for the environment. Now, though, as the world continually becomes more connected, and people have the ability to track their products and their personal impact on the world, everyone has the power to monitor and pressure companies to clean up their acts.

Image: Greenpeace

But looking into these things isn't necessarily associating with environmentalism. It's simply understanding the way businesses work. Companies want to be able to tell stories about doing good to strengthen their brands and build stronger bonds with customers. It's why each year, new companies take Greenpeace's pledge.

It's why transparency is lauded more than ever. And it's why companies are widely promoting their corporate social responsibility work. Some are even going a step farther and becoming benefit corporations.

The danger with all of this is greenwashing. As people focus more on the future of the planet, companies realize they can fare better in the public eye with these commitments, and make them without a real plan of action.

"Amazon's 100% commitment, we were certainly excited to see," Pomerantz said. "But a wave of happy stories without any action... we have to make sure that is a conversation."

Another big risk is that companies like Amazon start to clean up their own power sources because of the pressure from customers and the industry, but they only do so myopically.

"For the tech sector to really leverage all of its influence, it needs to impact government decisions as well," Pomerantz said. "The risk is...they focus just on those in the narrowest sense without trying to change the broader system around them."

Working on their own processes is key for morale and branding, but as for impacting climate change, it doesn't make much of a difference. Rather, Stepp said, tech companies are mostly influencing consumer behavior through their products, like Google buying Nest, AT&T and its work on connected cars, Verizon and its smart home technologies.

This extends to startups in the industry, as well. As the cleantech space becomes more crowded, it's important to make sure companies are moving the narrative in the right direction: awareness, then action -- which could be the key to influence other industries such as energy, retail, travel, and manufacturing.

If they don't, they're leaving a lot of opportunity unfulfilled. For them as successful businesses. For recruiting potential customers. For garnering good press. And for preserving the environment.

"The tech companies won't usher in the grand low-carbon energy transformation we need, but they will be an enabler of it," Stepp said.

The next wave

2015 will be a telling one for clean technology. Not only will climate change politics come to be more defined and regulations brought to the table, but technologies will have to expand beyond California to areas -- like Virginia -- that are more reluctant to adopt them.

Apple made a realistic energy goal and achieved it. From the moment the company pledged it would power data centers with renewable energy, it only took two years for them to go from fossil fuels to 100% clean energy. To make those changes, Apple had to work with Duke Energy, the largest utility in the US, which uses mostly coal and nuclear plants to power its grid.

The combined lobbying of Apple, Google, and Facebook, who all have data center projects in North Carolina, has forced Duke to make even larger scale changes since then. The utility announced it will build three solar facilities in the state and it has also signed five power purchase agreements (PPAs) with solar energy generation developers, which means a $500 million invested in renewable energy and 278 megawatts of generated solar power for the state. That's just a piece of its broader plan to invest $2 billion in renewable power around the world by 2018.

With PPAs, which are long-term financial commitments to buy renewable energy through specific utilities, tech companies have dramatically impacted the way states develop clean energy facilities. For example, Google has five large-scale PPAs in places like Iowa, Oklahoma, and Sweden. They've also worked with Duke in North Carolina to create a green tariff that allows them and other large energy customers to more easily choose renewable energy. As Google and other companies rapidly grow their footprints in states like Oregon, Utah, and Iowa, they have brought with them changes to utility agreements and energy policies.

But while tech companies lobby utilities, the the fossil fuel industry is lobbying lawmakers to make it more difficult for people to buy or lease renewable energy and curb environmental rules.

"We would like to see the industry come together to reach a point where choosing renewable energy is easy, where regulatory and market barriers are minimized and anyone who wants renewable energy has access to it," said a Google spokesperson.

The energy and tech industries will have to work together to make net metering (the way utilities resell renewable energy generated by homes) and permitting -- which are both processes that often make installing solar more expensive and slow -- easier.

"New business models will be at the heart of transforming [and] accelerating adoption of renewable energy at scale." Melissa Gray, Rackspace

Consumers and businesses will also have to put pressure on the utility industry so that they can fully benefit from the energy they generate from their own renewable energy sources such as solar.

Climate change and sustainability are global issues, and tech companies can't deal with them without reaching beyond the boundaries of their own facilities and operations. That will require more talks with policymakers, more lobbying, and more fights with the fossil fuel industry, which has a huge stake and influence in government operations around the world.

Sitting in a board room in talks with Dominion Energy executives isn't as photogenic as a beautiful sprawling wind farm in Texas, but it does present an important opportunity for these companies to rework the narrative of climate change policy.

"Companies can think big and aim not to sort of clean up their problem in the narrowest way possible, but to really create [systemic] change," Pomerantz said.

Many years of stereotypes, radical protests and campaigns, and lawsuits have plagued the environmental movement. But the world is moving from paper to digital; from large scale manufacturing to custom creation; and from coal plants to solar farms. It's becoming more clear that innovation by the multi-billion dollar companies who power our increasingly precious resource called the internet, and the passion behind environmentalism, don't have to be mutually exclusive. And they certainly don't have to be enemies.

In fact, the combination of the two might be humanity's best hope to drive swift and significant changes in the years ahead.