Hard yakka cultivates an internet of modern farming

An abundance of fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, and seafood are always on display when we walk into our local supermarket. But how often do any of us really think about the efforts our local farmers go through to make sure this fresh produce is available at our disposal?

Connected cows

(Image: Supplied)

connected-cows.jpg

The pressure on farmers to continue to produce at the same rate -- or even higher -- is set to worsen as worldwide predictions have concluded that we will face a global food shortage crisis in less than 50 years. Findings in the latest report (PDF) by the Global Harvest Initiative show that the world population will exceed 9 billion people in 2050, and, as a result, the demand for food is likely to outpace the amount that can be produced.

This echoes a similar prediction (PDF) made by the Australian government's Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Forestry, which highlighted that in order for Australia to maintain a stable food security level, there is a need to increase global agricultural output by 70 percent by 2050.

Australia's agricultural sector accounts for 2.4 percent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). However, in recent times, according to the National Farmers' Federation, agricultural productivity growth has slowed to 1 percent per annum, illustrating the need for the sector to look at new ways to ensure that the industry is able to keep up with growing population demands.

Justin Goc and his team at Tasmania's Barilla Bay Oysters have been working closely with Sense-T -- a collaboration between the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), the University of Tasmania, IBM, and the Tasmanian government -- to identify how sensing technology can help Tasmania's agricultural community drive future stability.

As part of the project, biological indicators were installed throughout the farm. For the last two years, the indicators have been measuring environmental factors such as the salinity in water, the temperature in and out of water, and wind levels. The data collected from these indicators is now being collated to create a catalogue.

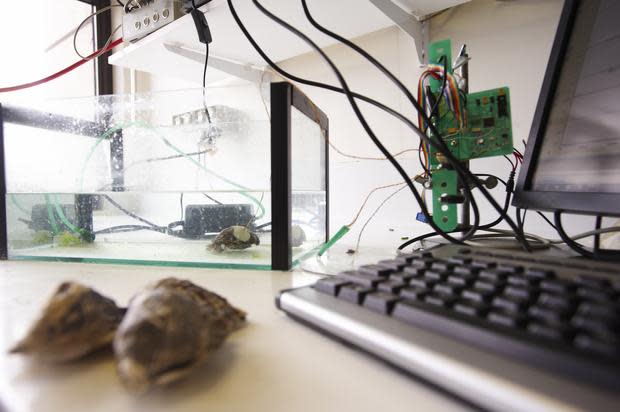

Lab oysters with sensors

(Image: Supplied)

lab-oysters-with-sensors.jpg

Goc, the general manager of Barilla Bay Oysters, said that ideally, he would eventually like to see the data play a role in assisting the farm to figure out the mystery of why oysters fatten up or don't fatten up.

"It can be a massive waiting game; sometimes it could just occur, and other times it doesn't. Usually, it's called seasonality. Why that is, the data may be able to shed some light over it," he said.

Goc also believes that the technology may potentially be useful in helping the farm to further understand the biology behind oysters.

"If we've got elevated temperatures and a lack of wind, then we will know if we're going to get an extended period of warmer weather, then that means we may have to accelerate our growing programs, because the oysters will grow quicker. This is instead of six weeks, where you might have to do it in four weeks to get the same outcome that you did before," he said.

"All of these things can then be cross-referenced and help build a catalogue. We hope we can draw parallels between seasons and understand the biology of the animal, how it works, and why it's happy and why it isn't happy."

However, Goc said that using technology in oyster farming can never replace a farmer's experience; rather, it would act as an assistant, to help fine tune their existing knowledge.

"With oyster farmers, you can never discount the raw experience of dealing with your lease areas and learning the information yourself. These concepts are only there to help and assist our experience."

CSIRO's soil moisture sensor

(Image: Supplied)

soil-measure.jpg

For crop growers, the CSIRO has been trialling the phenonet system, a sensor network that collects information and monitors plants, soil conditions, irrigation levels, and other environmental conditions such as weather patterns to help farmers become better informed about which crops they should plant to get a better harvest.

Arkady Zaslavsky, CSIRO digital productivity senior principal research scientist, said during a Gartner presentation in February that farmers are after information that will let them know what they need to do.

"Not only from experience, but through the use of science, so they need to know the weather forecast, when to irrigate, how much fertilisation to put in, and so on."

He highlighted, though, that only a small percentage of the information collected from the fields is considered valuable.

"We collect the data from the field every five minutes, where there is a sensor reading of about 20 bytes. When you multiply that by the amount of sensors in the amount of plots, where there is potentially over 1 million plots, we are dealing with petabytes of agricultural data just coming from digital agricultural fields.

"Now, if we look at this data in terms of what is useful for processing, it turns out that 99.95 percent of that data is useless. Only 0.5 percent of the data is called 'golden' data points, which we use for processing and visualising," he said.

At the same time, researchers from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) are now looking at the possibility of using robots to help crop farmers improve their productivity. QUT has designed a prototype AgBot II equipped with cameras, sensors, and software that can navigate, detect, and classify weeds and manage them either chemically or mechanically. It has also been designed to apply fertiliser for site-specific crop management. Trials of the technology are expected to commence in June 2015.

QUT robotics professor Tristan Perez said there is enormous potential to give farmers access to data that will assist them in management decisions, particularly given that weed and pest management in crops is a serious problem. He added that the AgBots could potentially replace large, expensive tractors, and work 24 hours a day.

Queensland University of Technology's AgBott II prototype

(Image: Supplied)

165426944191fbce907f1k.jpg

"There is enormous potential for AgBots to be combined with sensor networks and drones to provide a farmer with large amounts of data, which ... can be combined with mathematical models and novel statistical techniques (big data analytics) to extract key information for management decisions -- not only on when to apply herbicides, pesticides, and fertilisers, but how much to use," he said.

Meanwhile, cows are being tagged with collars installed with GPS tracking to enable farmers to locate their herds, identify where they go and where they feed, and examine the health of each individual animal. The CSIRO is currently trialling the technology in its Smart Farm in New England, New South Wales, and Smart Homestead in Townsville, Queensland.

Zaslavsky said one of the biggest challenges that the data collected from the cows -- roughly 200MB of data per cow each year -- helps farmers address is in early detection of when an animal becomes sick. This enables farmers to separate the individual animal from the herd and maintain the health of the others.

Raja Jurdak, CSIRO autonomous systems principal research scientist, added that the vision the CSIRO has for the Smart Farm is for all the information collected from the cows to be fed back to farmers on a single dashboard, creating a support system to better manage farms. For example, it could help farmers decide when they should bring their animals in, when to irrigate, and when there are abnormalities in an animal's behaviour.

"[Farmers] would often have infrequent access to information, and, if they do, it's often through manual inspection by having the animal on a scale. Typically, it's very labour intensive to get the animals there," he said.

"With the new approach, you'd have a structure and an automated scale with data connectivity, and that would facilitate the process a lot more."

Jurdak added that the organisation sees the potential of using the collars for sheep farming, too, as farmers are looking to trace where each animal goes, where it grazes, the quality of its milk, and the state of its wool.

"We've tested some sensors on some pregnant sheep, because when a sheep is pregnant, there is a certain pattern of movement that characterises that they are pregnant. Our sensors can detect that movement, so we can closely monitor the sheep at that time to make sure that when it gives birth, it's a healthy lamb," he said.