Ransomware has been around for almost 30 years, so why does it feel like it's getting worse?

Ransomware is not new. The malware, which encrypts data and demands payment in exchange for decryption keys, has been with us for almost 30 years.

So why does it feel like it's getting worse? Well, that's because it is getting worse.

SEE ALSO: A new ransomware is sweeping the globe, but there's a vaccine

In seemingly no time at all, ransomware has gone from an obscure threat faced by a select few to a plague crippling hospitals, banks, public transportation systems, and even video games. Frustratingly, the explosive growth of ransomware shows no signs of abating — leaving victims wondering why them, and why now?

The answer to both of those questions involves cryptocurrency and the National Security Agency.

But first, a little history

The first known ransomware attack hit the healthcare industry way back in 1989. According to the cybersecurity blog Practically Unhackable, a biologist by the name of Joseph Popp sent close to 20,000 floppy disks to researchers claiming they contained a survey which would help scientists determine a patient's risk for contracting HIV.

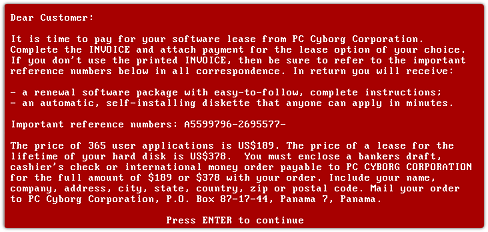

What was left unmentioned in the promotional material was that the disks also encrypted file names on infected computers — rendering them practically unusable. Instead of their typical boot screens, victims were shown a message demanding a $189 payment in order to unlock the system.

Image: Palo Alto Networks

Popp, who had a PhD from Harvard, was an evolutionary biologist and fell outside of what we think of today as a stereotypical hacker. According to The Atlantic, after he was arrested and charged with blackmail, Popp insisted that he intended to donate the proceeds from his scheme to HIV-related research.

Regardless of his true motives, the success of Popp's attack was limited by two key factors: The floppy disks were sent out via the mail system, and the encryption employed by what became known as PC Cyborg was reversible without his help.

Twenty-eight years later, things have changed for the worse in the world of ransomware.

Cryptocurrency and the NSA

When we talk about the scale of modern ransomware attacks, it's important to keep two criteria in mind: frequency and reach.

A 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Justice noted 7,694 ransomware complaints since 2005, which it acknowledged is probably undercounting the number of actual attacks. The May WannaCry ransomware, for its part, hit over 150 countries. Two factors played a key role in those jaw-dropping figures: the rise of cryptocurrency and the availability of dumped hacking exploits hoarded by the NSA.

Cryptocurrency like Bitcoin allows attackers a real shot at actually receiving ransom payments. In a major step up from the payment mechanism implemented by Joseph Popp, hackers no longer need to set up a PO box and hope the physical cashier's checks flow in. Instead, they can simply direct victims to make payments to specific Bitcoin addresses.

According to the cybersecurity company Palo Alto Networks, the first ransomware to demand payment in Bitcoin was the 2013 Cryptowall. It was by no means the last, however. The relative ease of cryptocurrency payments combined with the growing popularity of Bitcoin surely contributed to what a 2016 IBM report found was a 300 percent increase in ransomware incidents over the preceding year.

Image: B. TONGO/EPA/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

As for the growing reach of such attacks? While there are many factors at play, one obvious inflection point can be found in the April Shadow Brokers dump where the hacking group notoriously released a host of exploits originating from the National Security Agency. Among that list was one vulnerability by the name EternalBlue, which, when paired with ransomware, allowed for the worm-like propagation of the WannaCry attack.

The same exploit reportedly played a key (but not exclusive) role in the spread of NotPetya — ransomware that has hit at least 65 countries and whose likely primary goal is to cause destruction.

And while Microsoft had already released a patch for EternalBlue by the time is swept the globe, the wildfire spread of WannaCry and NotPetya serve as a stark reminder that not everyone stays up to date with security patches.

So where does that leave us?

The unprecedented scale of these two attacks, powered by stolen NSA exploits and facilitated by cryptocurrency, suggests we have entered a new age of virulent ransomware. To make matters worse, attacks like WannaCry are likely to become more common, not less, as evidenced by a 2017 report from cybersecurity firm Symantec which found "a 36 percent increase in ransomware attacks worldwide."

Interestingly, however, ransomware may end up becoming a victim of its own success. The sheer number of infected computers, combined with the practically nonfunctional payment mechanisms of both NotPetya and WannaCry, mean that even if people did elect to pay the ransom, they weren't going to get their decryption keys.

Why pay up if you know you're not getting your files back either way?

And the word has gotten out. At the time of this writing, the Bitcoin address associated with NotPetya has received only 46 payments totaling approximately $10,317.

All of this suggests that while the form of digital extortion first developed by Joseph Popp shows no signs of slowing down, the money may no longer be in it. And that, in the end, may be the only hope we have of an end to the growing ransomware scourge.

WATCH: Step inside the secretive class that turns people into hackers